Abstract

Introduction

The cancer risk of radiation exposure in the moderate-to-high dose range has been well established. However, the risk remains unclear at low-dose ranges with protracted low-dose rate exposure, which is typical of occupational exposure. Several epidemiological studies of Korean radiation workers have been conducted, but the data were analysed retrospectively in most cases. Moreover, groups with relatively high exposure, such as industrial radiographers, have been neglected. Therefore, we have launched a prospective cohort study of all Korean radiation workers to assess the health effects associated with occupational radiation exposure.

Methods and analysis

Approximately 42 000 Korean radiation workers registered with the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission from 2016 to 2017 are the initial target population of this study. Cohort participants are to be enrolled through a nationwide self-administered questionnaire survey between 24 May 2016 and 30 June 2017. As of 31 March 2017, 22 982 workers are enrolled in the study corresponding to a response rate of 75%. This enrolment will be continued at 5-year intervals to update information on existing study participants and recruit newly hired workers. Survey data will be linked with the national dose registry, the national cancer registry, the national vital statistics registry and national health insurance data via personal identification numbers. Age-specific and sex-specific standardised incidence and mortality ratios will be calculated for overall comparisons of cancer risk. For dose–response assessment, excess relative risk (per Gy) and excess absolute risk (per Gy) will be estimated with adjustments for birth year and potential confounders, such as lifestyle factors and socioeconomic status.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has received ethical approval from the institutional review board of the Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (IRB No. K-1603-002-034). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment. The findings of the study will be disseminated through scientific peer-reviewed journals and be provided to the public, including radiation workers, via the study website (http://www.rhs.kr/) and onsite radiation safety education.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective cohort study of ‘radiation workers’, including all occupations.

Data linkage of the national health resources including cancer, non-cancer disease and laboratory biomarkers.

Adjustment for potential confounding variables.

Limited sample size and retired workers not included in the cohort.

Continued long-term follow-up is necessary to extract full value from the cohort.

Introduction

Studies of workers in radiation-related occupations provide an opportunity to assess the health risks of low-dose ionising radiation exposure. Various epidemiological studies of occupational exposure to ionising radiation have been conducted in the form of national or international collaborative studies.1 2 Adverse health effects, such as all cancers other than leukaemia combined, lung cancer, leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and circulatory diseases, have been reported in some single-nation studies, from the UK,3 Russia,4–6 the USA,7–11 Canada12 and France.13 In addition, a recent international large-scale cohort study indicated an increased risk of cancer from protracted low-dose exposure.14 15 Although these international efforts have been able to accumulate scientific evidence of health effects in occupationally exposed populations and provided more precise dose–response estimates than single-nation studies, findings from these studies at low-dose ranges, particularly <100 mSv, should be still interpreted with caution due to wide confidence intervals for risk estimates and limited information on confounders. Moreover, given that baseline risks possibly differ from nation to nation, generalisations of the findings to other populations should be made with caution. Thus, to supplement international collaborative studies, it is important to evaluate the health effects of low-dose ionising radiation in national studies reflecting the characteristics of the particular country, including comprehensive information on confounding factors.

In Korea, workers in radiation-related occupations are registered with two independent government agencies depending on their occupation: diagnostic radiation workers under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and nuclear-related workers under the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (NSSC). We use the term ‘radiation workers’ for nuclear-related workers henceforth in this paper. A prospective cohort study of diagnostic radiation workers was launched about 5 years ago16 17 following the suggestion of an elevated cancer risk in diagnostic medical workers from a retrospective study.18 For Korean radiation workers, sparse information is available from two studies that are limited by a short follow-up and sparse information on confounding variables.19 20 Moreover, industrial radiography, which is one of the non-destructive testing (NDT) technologies, has been reported to not only have the highest effective dose,21 but also to account for the majority of occupational cancer incidence among all radiation-related occupations.22 23 However, industrial radiographers have been relatively neglected compared with nuclear power plant workers.

Therefore, we have launched a prospective cohort study of all Korean radiation workers, including industrial radiographers, to assess the health effects associated with protracted low-dose radiation exposure, which has comprehensive information on potential confounding variables and long-term follow-up.

Methods and analysis

Study population and design

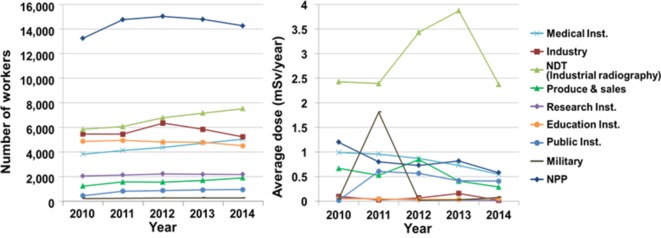

The Korean radiation workers study (KRWS) is a prospective cohort study, and the initial target population includes approximately 42 000 Korean radiation workers registered with the NSSC from 2016 to 2017. Korean radiation workers are categorised into 10 occupations depending on their workplace: nuclear power plant, industrial radiography, industry, medical institute (except diagnostic radiation workers), education institute, public institute, military, production and sales. Of these, nuclear power plant workers are in the majority with >14 000 workers, followed by industrial radiography and industrial workers.21 Average annual effective doses, which are the sum of the external dose (Hp(10)) and the committed effective dose, in the last 5 years have been reported to be below or near 1 mSv; however, industrial radiographers are exposed to the highest doses of 2–4 mSv.21 The number of workers and their annual average effective doses by occupation in the past 5 years are presented in figure 1.21

Figure 1.

Number of Korean radiation workers and effective doses (mSv) according to occupation. NDT, non-destructive testing; NPP, nuclear power plant.

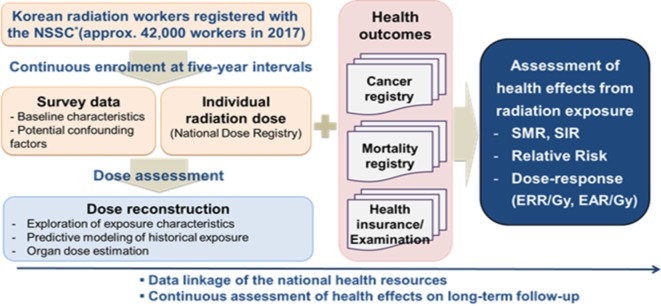

All radiation workers in Korea should receive radiation safety education every year. In order to enrol the participants, we visited each educational location across the country between 24 May 2016 and 30 June 2017, to conduct the self-administered questionnaire survey and collect informed consent, the details of which are described in the following section. As of 31 March 2017, of 30 572 workers that participated in radiation safety education, 22 982 workers have been enrolled in the study, which corresponds to a response rate of 75%. Following enrolment, we shall combine the data from the questionnaires with dosimetry data from the national dose registry, and link the health data via personal identification numbers. The health data will include cancer incidence data from the national cancer registry, overall mortality data from the national vital statistics registry and incidence of diseases other than cancer from national health examination data. We will conduct the self-administered questionnaire survey at 5-year intervals to update information on existing study participants, recruit newly hired workers and evaluate the association between radiation dose and health effects on long-term follow-up. The study design is presented in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study design. EAR, excess absolute risk; ERR, excess relative risk; NSSC, Nuclear Safety and Security Commission.

Survey questionnaire and informed consent form

A self-administered questionnaire was developed by referring to the previous cohort studies of Korean diagnostic radiological technologists and the US radiologic technologists (USRT),24 25 which was amended through a pilot survey. The questionnaire was composed of 20 questions about general work history and lifestyle factors, and 10 demographic questions for all radiation workers (table 1). The 20 questions asked to all workers covered occupational history, work practices, exposure warnings, medical exposure, medical history and lifestyle factors. For industry radiographers only, we added 11 NDT-specific questions in order to collect more detailed information on their work status and exposure to other harmful agents. These additional questions for industrial radiographers included specific working types, history of specific health examination and exposure to other NDT-related harmful agents, such as film developer and cleaning fluids. In addition to the survey questionnaire, an informed consent form was developed based on the Privacy Act in Korea,26 which included five essential items about the collection and use of personal information, collection and use of identifying information, collection and use of sensitive information, sharing of personal information with third parties and consent to research participation.

Table 1.

Items collected in the survey questionnaire

| Domains | Items |

| Occupational history | Calendar year of hiring, duration of employment, employment status and frequency of radiation procedures |

| Work practices | Badge wearing, use of shield wall, wearing of protective equipment, radiation sources and distance from radiation sources |

| Experience of high radiation exposure | Warning for exceeding 5 mSv/quarter and lower white cell count levels than normal |

| Medical radiation exposure | Plain radiography, intraoral or panoramic radiography, CT, fluoroscopy, nuclear medicine imaging, nuclear medicine therapy, mammography, interventional radiography and radiation therapy |

| Medical history | Cancer, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, cataracts, diabetes and so on (30 diseases) |

| Lifestyle factors | Sleep pattern, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise and night shifts |

| Demographics | Name, age, sex, education level, marital status, height, weight and contact details |

Dosimetry data

We shall collect radiation doses for individual workers from the Central Registry for Radiation Worker Information (CRRWI) managed by the NSSC. External and internal doses are collected by measuring personal dose equivalent, Hp(10), and committed effective doses quarterly and annually, respectively, through the electronic dose record database (the National Dose Registry), which has been available under the CRRWI since 1984. Most external doses are measured using thermoluminescent dosimeters; optically stimulated luminescence dosimeters are only applied in limited fields.27 Film badge dosimeters were used in the past, but are no longer used. Doses based on film badge dosimeters are <10% of the total dose records.28 It might be challenging to ensure the inclusion of radiation doses from high-linear energy transfer (LET) exposure (eg, neutrons) in the current Korean dose reporting system in which Hp(10) for neutrons is included but it is not separated from Hp(10) for photons; however, as the proportion of workers with potential high-LET exposure is expected to be <5%, the impact of high-LET exposure on risk estimates would be minimal. Committed effective doses are reported only for workers whose annual committed effective dose is likely to exceed 2 mSv/year. In addition to radiation dose, the database includes workers’ names, sex, job classification and personal identification numbers including date of birth.28 For individuals who were working before 1984, radiation doses were not documented; therefore, we will estimate their historical occupational exposure using a dose reconstruction model that includes predictors such as age, sex and work place.29 For using individual radiation doses to analyse a dose–response relationship, we will use organ absorbed doses estimated from the effective dose from the external exposure in the National Dose Registry. Absorbed organ dose is estimated based on methods using the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) 116 organ dose conversion coefficients and irradiation geometry factors,30 considering information about work practices, such as use of protective devices and badge location, from the nationwide survey as suggested by the Million Worker Study 31 and the USRT study.32

Health outcomes

Health information for individual workers in this study is to be collected from the National Cancer Registry, the National Vital Statistics Registry and the National Health Insurance Sharing Service (NHISS) database (table 2). The National Cancer Registry includes cancer incidence data and the National Vital Statistics Registry includes mortality data, which have been available since 1999 and 1992, respectively. The NHISS database consists of four major sub-datasets, including an eligibility database, medical treatment database, health examination database and medical care institution database, which have been available since 2002.33 34 We will predominantly use the first three databases and the information derived from these databases includes medical care history, regular health check-ups and socioeconomic variables.

Table 2.

Health data collected from the national sources

| National sources | Major items |

| National Cancer Registry | Cancer code (ICD-10), site, stage, diagnosis method and date of diagnosis |

| National Vital Statistics Registry | Date of death and cause of death |

| National Health Insurance Sharing Service | Eligibility database (14 variables): date of birth, type of eligibility, gender, income level, disability and so on |

| Medical treatment database (56 variables): records of inpatient and outpatient usage (length of stay, treatment costs, services received and so on), diagnosis (ICD-10 codes), prescription and so on | |

| Health examination database (41 variables): health behaviours from questionnaire, general health examination data including cancer screening and laboratory test items (eg, blood cell counts, cholesterol levels, triglyceride concentration, fasting blood sugar, liver enzyme tests (aspartate aminotransferase/serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, alanine aminotransferase/serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, gamma-glutamyltransferase), serum creatinine, urinary protein and estimated glomerular filtration rate) and so on. |

ICD-10, International Classification of Disease, 10th revision.

Validity and reliability of self-administered questionnaires

Information collected from self-administered questionnaires is essential for estimating organ doses and determining confounders, which can interpret findings more accurately. It is therefore of particular importance that we evaluate the validity and reliability of our questionnaires, particularly those measuring work practice and lifestyle. Our questionnaire contains items about work history (eg, employment start date and period, and warning for exceeding 5 mSv) and medical history (eg, diagnosis of cancer, cataract and cardiovascular disease), which we can also ascertain from the National Dose Registry and National Health Records (ie, the cancer registry and NHISS database). We will compare the answers with our questions with the national records in order to assess the validity of the responses to the self-administered questionnaires. For the evaluation of reliability, we will compare responses of study participants who were surveyed in both 2016 and 2017. Intraclass correlation coefficients35 and kappa coefficients36 37 will be used as measures of validity and reliability.

Health risk associated with ionising radiation exposure

The primary health outcome of this study is cancer incidence. Other outcomes include incidence of non-cancer diseases (eg, cataracts and circulatory disease), laboratory biomarkers (ie, laboratory test items) from the NHISS databases and mortality. The laboratory biomarkers are possibly associated with predisease conditions, such as metabolic risk profile (eg, obesity, high serum glucose, cholesterol level and low blood pressure) and abnormal blood cell counts. For example, the metabolic risk profile can be considered a surrogate endpoint of cardiovascular disease, and also an independent variable to explore an interaction effect between radiation exposure and metabolic syndrome with regard to cardiovascular disease. Age-specific and sex-specific standardised incidence and mortality ratios will be calculated for overall comparisons of cancer risk. The national statistics for cancer incidence and mortality among the general Korean population will be employed as the control group for external comparison, and study subjects whose effective doses (the sum of the external dose (Hp(10)) and the committed effective dose) have not exceeded the minimum recording level of 0.1 mSv/quarter for external exposure and 0.1 mSv/year for internal exposure during their employment according to the National Dose Registry shall be considered as the control group for internal comparison. Risk estimates for radiation exposure are typically presented as excess relative risk (ERR) and excess absolute risk (EAR). The ERR is the relative risk minus 1.0, which refers to the magnitude of the radiation risk relative to the baseline. The EAR refers to the difference between the rate in an exposed and an unexposed population. To quantify the dose–response relationship, we will estimate health risk per unit of organ absorbed dose (ie, ERR/Gy, EAR/Gy) using a parametric model (Poisson), penalised splines and/or Bayesian semiparametric models38 with or without adjustment for birth cohort and confounding factors, such as lifestyle and socioeconomic status. Committed effective dose will be used as another confounder for sensitivity analyses considering internal exposure, using an adjusted analysis and a stratified analysis. Person-years at risk for the analysis are calculated from date of entry in the study (defined as the latest among the date of the first exposure and date of start of follow-up period in the national health data source) to date of exit (defined as the earliest among the date of health events, date of loss to follow-up and date of end of follow-up). To allow for a possible latency period between radiation exposure and its consequences, cumulative doses will be lagged by 2–5 years for leukaemia and 5–10 years for solid cancers. All the analyses will be updated at follow-up intervals of 3–5 years.

Sample size calculation

As this study is designed to investigate radiation-related health effects with long-term follow-up in a cohort targeting all Korean radiation workers, a sample size calculation is not deemed relevant.

Study limitations and future work

Lack of statistical power is a major limitation in most epidemiological studies, particularly for low-dose ranges (ie, <100 mSv). Average annual dose for the KRWS’s population in the past 5 years is approximately 1 mSv (0–4 mSv depending on occupation).21 Given that there was still a lack of statistical power in low-dose ranges in the recent large scale international Nuclear Workers Study (INWORKS) with an average individual cumulative dose of 21 mGy,15 this study including a relatively young cohort would not allow a definitive conclusion in a short period of time. In addition, this study is limited in terms of investigation of health effects in women as the proportion of female workers in the cohort is expected to be 10%–20%.28 39 Thus, it is necessary to expand the cohort through continuous enrolment of new radiation workers with a long follow-up, and through collaborative studies, including with the Korean diagnostic radiation worker cohort and international cohorts of similar occupations, such as the INWORKS15 and the USRT.40 Another limitation is that the current KRWS does not include retired workers and has limited information of radiation doses for those who had worked before 1984 since the electronic National Dose Registry was not available before. As the beginning of nuclear activities in Korea, a research reactor was first introduced at 1962, and the first nuclear power plant opened in 1978.41 Given that the average annual occupational doses were 1–3 mSv before 2000,28 the radiation dose of retired workers is expected to be higher, and their ages to be higher than those of currently active workers of the KRWS cohort. Thus, it is important to include them in potential future studies, as this could possibly increase statistical power, via an increase in the number of events and larger exposure variance.42 43 In addition, collection of biosamples, such as blood and buccal cells, should be considered for a comprehensive understanding of biological mechanisms via molecular epidemiological studies of radiation risk.44 These activities will enhance our ability to investigate susceptibility and surrogate biomarkers for assessing exposure risk, and thereby develop more sophisticated dose–response models for low-dose risk assessments.

Potential impact

We have designed the KRWS to assess health effects among Korean radiation workers exposed to protracted low-dose radiation. This is the first prospective cohort study of active workers from the entire range of occupations registered with the NSSC. Data collected from the nationwide survey will provide detailed information on work practices and lifestyle factors, which allows for an in-depth exploration of occupational exposure and adjustment for confounding factors. In addition, individual health data derived from the national resources include not only cancer/non-cancer diseases, but also predisease conditions including laboratory test items, ensuring comprehensive and accurate information for the evaluation of health effects from radiation exposure. Study findings will be directly relevant to radiation protection for radiation workers and will further provide the basis for recommendations and regulations about low-dose radiation safety.

Besides establishing scientific evidence for radiation-related health effects, we expect that this study will contribute to both the prevention of adverse health effects and improved communication with radiation workers. We will continue to promote this cohort study and its results via radiation safety education and the study website (http://www.rhs.kr/), which is a former website for Korean diagnostic radiation worker studies,16 17 that has been combined with the KRWS to increase understanding about occupational exposure and health effects. Consequently, radiation workers will be encouraged to pay more attention to radiation protection in their workplaces and to accomplish their work duties with a balanced risk judgement about potential exposure that is not solely based on perceived risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to Kijung Lim from the Korea Foundation of Nuclear Safety (KOFONS) for providing his professional knowledge regarding the National Dose Registry for radiation workers.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS and YWJ: conceived and designed this study and drafted the manuscript. WYL and DNL: are involved in coordination of the nationwide survey. WYL, DNL and JUK: are involved in the collection of data and the construction of the cohort database. ESC and YJB: designed the survey questionnaire. WJL and SP: contributed to the design of the study and provided valuable inputs relevant to study implementation. YWJ: obtained funding. All authors: reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Nuclear Safety Research Program through the Korea Foundation of Nuclear Safety (KOFONS), and granted financial resources by the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (NSSC) of the Republic of Korea (no. 1503008).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study has received ethical approval from the institutional review board of the Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (IRB No. K-1603-002-034).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cardis E, Vrijheid M, Blettner M, et al. . The 15-country collaborative study of cancer risk among radiation workers in the nuclear industry: estimates of radiation-related cancer risks. Radiat Res 2007;167:396–416. 10.1667/RR0553.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seong KM, Seo S, Lee D, et al. . Is the linear no-threshold dose-response paradigm still necessary for the assessment of health effects of low dose radiation? J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:S10–23. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.S1.S10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muirhead CR, O’Hagan JA, Haylock RG, et al. . Mortality and cancer incidence following occupational radiation exposure: third analysis of the national registry for radiation workers. Br J Cancer 2009;100:206–12. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert ES, Koshurnikova NA, Sokolnikov ME, et al. . Lung cancer in mayak workers. Radiat Res 2004;162:505–16. 10.1667/RR3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter N, Kuznetsova IS, Labutina EV, et al. . Solid cancer incidence other than lung, liver and bone in Mayak workers: 1948-2004. Br J Cancer 2013;109:1989–96. 10.1038/bjc.2013.543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shilnikova NS, Preston DL, Ron E, et al. . Cancer mortality risk among workers at the Mayak nuclear complex. Radiat Res 2003;159:787–98.doi:10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0787:CMRAWA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajaraman P, Doody MM, Yu CL, et al. . Incidence and mortality risks for circulatory diseases in US radiologic technologists who worked with fluoroscopically guided interventional procedures, 1994-2008. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:21–7. 10.1136/oemed-2015-102888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preston DL, Kitahara CM, Freedman DM, et al. . Breast cancer risk and protracted low-to-moderate dose occupational radiation exposure in the US Radiologic Technologists Cohort, 1983-2008. Br J Cancer 2016;115:1105–12. 10.1038/bjc.2016.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matanoski GM, Tonascia JA, Correa-Villaseñor A, et al. . Cancer risks and low-level radiation in U.S. shipyard workers. J Radiat Res 2008;49:83–91. 10.1269/jrr.06082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson DB, Wing S. Leukemia mortality among workers at the savannah river site. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:1015–22. 10.1093/aje/kwm176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schubauer-Berigan MK, Daniels RD, Bertke SJ, et al. . Cancer Mortality through 2005 among a pooled cohort of U.S. nuclear workers exposed to external lonizing radiation. Radiat Res 2015;183:620–31. 10.1667/RR13988.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zablotska LB, Lane RS, Thompson PA. A reanalysis of cancer mortality in Canadian nuclear workers (1956-1994) based on revised exposure and cohort data. Br J Cancer 2014;110:214–23. 10.1038/bjc.2013.592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz-Flamant C, Laurent O, Samson E, et al. . Mortality associated with chronic external radiation exposure in the French combined cohort of nuclear workers. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:630–8. 10.1136/oemed-2012-101149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson DB, Cardis E, Daniels RD, et al. . Risk of cancer from occupational exposure to ionising radiation: retrospective cohort study of workers in france, the united kingdom, and the united states (INWORKS). BMJ 2015;351:h5359 10.1136/bmj.h5359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leuraud K, Richardson DB, Cardis E, et al. . Ionising radiation and risk of death from leukaemia and lymphoma in radiation-monitored workers (INWORKS): an international cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2015;2:e276–e281. 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00094-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WJ, Ha M, Hwang SS, et al. . The radiologic technologists’ health study in South Korea: study design and baseline results. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015;88:759–68. 10.1007/s00420-014-1002-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Cha ES, Jeong M, et al. . A national survey of occupational radiation exposure among diagnostic radiologic technologists in South Korea. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2015;167:525–31. 10.1093/rpd/ncu330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi KH, Ha M, Lee WJ, et al. . Cancer risk in diagnostic radiation workers in Korea from 1996 to 2002. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:314–27. 10.3390/ijerph10010314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong M, Jin YW, Yang KH, et al. . Radiation exposure and cancer incidence in a cohort of nuclear power industry workers in the Republic of Korea, 1992-2005. Radiat Environ Biophys 2010;49:47–55. 10.1007/s00411-009-0247-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahn YS, Park RM, Koh DH. Cancer admission and mortality in workers exposed to ionizing radiation in Korea. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:791–803. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318167751d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuclear safety and security commission, korea institute of nuclear safety, korea institute of nuclear nonproliferation and control. 2015 Nuclear Safety Yearbook, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. Annual reports of occupational disease (2000–2015). http://english.kosha.or.kr/english/content.do?menuId=11436 (accessed 20 Jun 2017).

- 23.Jin YW, Jeong M, Moon K, et al. . Ionizing radiation-induced diseases in korea. J Korean Med Sci 2010;25:S70–6. 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.S.S70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The U.S. radiologic technologists study. Division of cancer epidemiology & genetics. https://radtechstudy.nci.nih.gov/questionnaires.html (accessed 20 Jun 2017).

- 25.Radiation and health study among radiation workers in Korea. http://www.rhs.kr/method/overview.asp (accessed20 Jun 2017).

- 26.Personal Information Protection Act. Articles 15 to 22 Section 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee W-H, Kim S-C, Ahn S-M. Comparison on the dosimetry of TLD and OSLD Used in nuclear medicine. J Korea Contents Assoc 2012;12:329–34. 10.5392/JKCA.2012.12.12.329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SY, Kim TH, Chung CK, et al. . Analysis of radiation workers' dose records in the Korean National Dose Registry. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2001;95:143–8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi Y, Kim J, Lee JJ, et al. . Reconstruction of radiation dose received by diagnostic radiologic technologists in korea. J Prev Med Public Health 2016;49:288–300. 10.3961/jpmph.16.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taulbee TD, McCartney KA, Traub R, et al. . Implementation of ICRP 116 dose conversion coefficients for reconstructing organ dose in a radiation compensation program. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2017;173:131–7. 10.1093/rpd/ncw305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouville A, Toohey RE, Boice JD, et al. . Dose reconstruction for the million worker study: status and guidelines. Health Phys 2015;108:206–20. 10.1097/HP.0000000000000231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon SL, Preston DL, Linet MS, et al. . Radiation organ doses received in a nationwide cohort of U.S. radiologic technologists: methods and findings. Radiat Res 2014;182:507–28. 10.1667/RR13542.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. . Data Resource Profile: the national health information database of the national health insurance service in south korea. Int J Epidemiol 2016:dyw253 10.1093/ije/dyw253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Health Insurance Sharing Service in Korea. Details of DB and cost. https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba022eng.do (accessed 20 Jun 2017).

- 35.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:423–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furukawa K, Misumi M, Cologne JB, et al. . A bayesian semiparametric model for radiation dose-response estimation. Risk Anal 2016;36:1211–23. 10.1111/risa.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeong JH, Lee JK, Kwon JW, et al. . Occupational radiaiton exposure in Korea: 2002. J Korean Assoc Radiat Protect 2005;30:175–83. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boice JD, Mandel JS, Doody MM, et al. . A health survey of radiologic technologists. Cancer 1992;69:586–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim YK, Kim JR, Hwang KH, et al. . Investigation of nuclear development at the early stage in Korea: KAERI, 2009. (No. KAERI/CM–1022/2007). [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKeown-Eyssen GE, Thomas DC. Sample size determination in case-control studies: the influence of the distribution of exposure. J Chronic Dis 1985;38:559–68. 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90044-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White E, Kushi LH, Pepe MS. The effect of exposure variance and exposure measurement error on study sample size: implications for the design of epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:873–80. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90190-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pernot E, Hall J, Baatout S, et al. . Ionizing radiation biomarkers for potential use in epidemiological studies. Mutat Res 2012;751:258–86. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.