Participation of π– and n–π* (n = O and Npy; π* = Csp

2 and

and n–π* (n = O and Npy; π* = Csp

2 and  ) interactions in the equi-energetic conformations of 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazoles.

) interactions in the equi-energetic conformations of 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazoles.

Keywords: orthogonal nitro⋯C interaction, crystal structure, orthogonal nitro⋯N interaction, helix, conformational isomerism, high-Z′ structure, snapshot conformer

Abstract

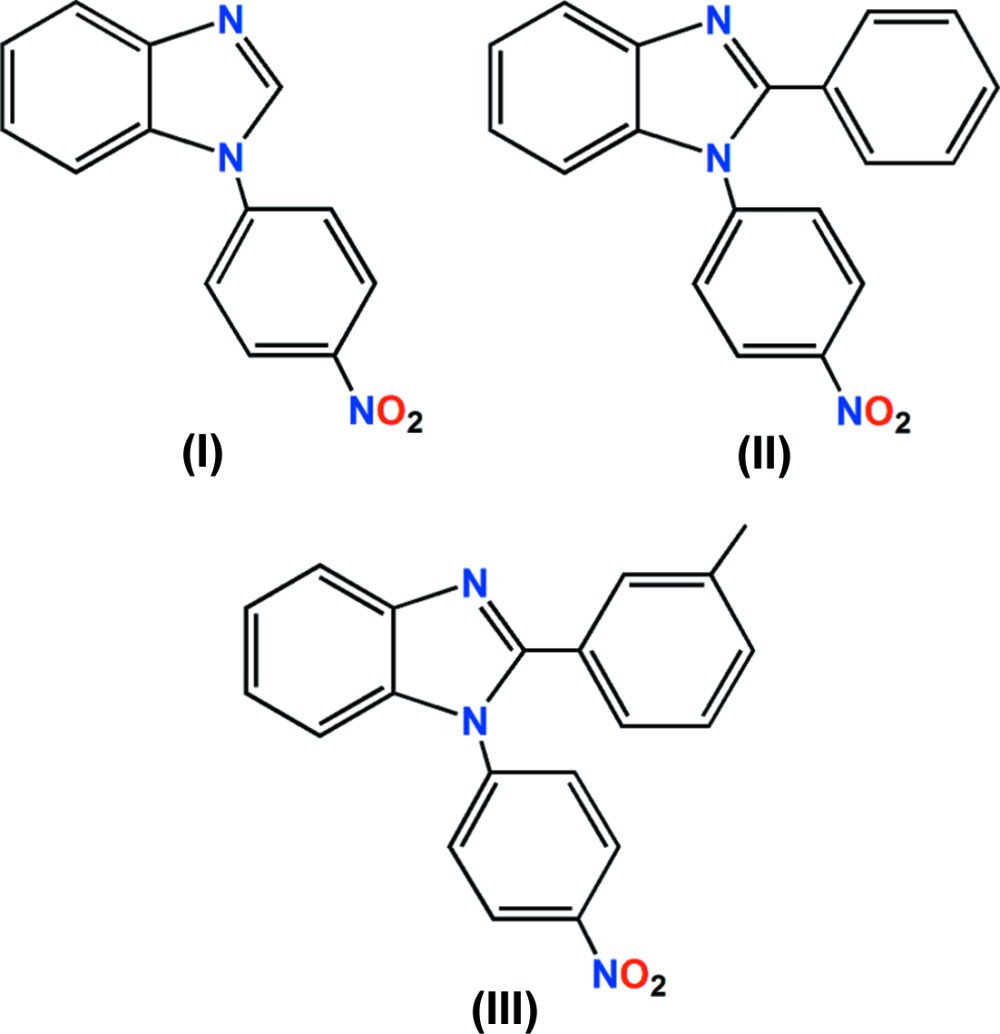

A detailed structural analysis of the benzimidazole nitroarenes 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, C13H9N3O2, (I), 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, C19H13N3O2, (II), and 2-(3-methylphenyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, C20H15N3O2, (III), has been performed. They are nonplanar structures whose crystal arrangement is governed by Csp

2—H⋯A (A = NO2, Npy and π) hydrogen bonding. The inherent complexity of the supramolecular arrangements of compounds (I) (Z′ = 2) and (II) (Z′ = 4) into tapes, helices and sheets is the result of the additional participation of π– and n–π* (n = O and Npy; π* = Csp

2 and

and n–π* (n = O and Npy; π* = Csp

2 and  ) interactions that contribute to the stabilization of the equi-energetic conformations adopted by each of the independent molecules in the asymmetric unit. In contrast, compound (III) (Z′ = 1) is self-paired, probably due to the effect of the steric demand of the methyl group on the crystal packing. Theoretical ab initio calculations confirmed that the presence of the arene ring at the benzimidazole 2-position increases the rotational barrier of the nitrobenzene ring and also supports the electrostatic nature of the orthogonal ONO⋯Csp

2 and Npy⋯NO2 interactions.

) interactions that contribute to the stabilization of the equi-energetic conformations adopted by each of the independent molecules in the asymmetric unit. In contrast, compound (III) (Z′ = 1) is self-paired, probably due to the effect of the steric demand of the methyl group on the crystal packing. Theoretical ab initio calculations confirmed that the presence of the arene ring at the benzimidazole 2-position increases the rotational barrier of the nitrobenzene ring and also supports the electrostatic nature of the orthogonal ONO⋯Csp

2 and Npy⋯NO2 interactions.

Introduction

Benzimidazoles are recognized as essential chemical motifs present in a variety of natural products, agrochemicals and bioactive molecules (Keri et al., 2015 ▸). Particularly, C2-aryl-substituted benzimidazoles are often found as a key unit in various natural compounds, biologically active agents, potent pharmacophores and functional chemicals (Horton et al., 2003 ▸; Kumar, 2004 ▸; Candeias et al., 2009 ▸; Gupta & Rawat, 2010 ▸; Carvalho et al., 2011 ▸). In addition, N-arylbenzimidazoles are a class of prominent heterocyclic compounds that exhibit a wide range of biological properties (Sabat et al., 2006 ▸; Elias et al., 2011 ▸). In particular, 1,2-diarylbenzimidazoles have been reported as strong inhibitors of human cyclooxygenases with a skewed selectivity towards the COX-2 (cyclooxygenase 2) isoform at the micromolar level (Secci et al., 2012 ▸).

It is worth mentioning the case of 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (I), which has been reported as an inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), which is highly expressed in tumour cells (Zhong et al., 2004 ▸; Katritzky et al., 2005 ▸). Experimental evidence indicates that the inhibitory activity involves discrete noncovalent dipolar protein–ligand interactions, which significantly contribute to the binding affinity and to intermolecular recognition. On the other hand, little is known about the nature of the noncovalent interactions of nitroarenes with hydrophobic aromatic protein  areas and their contribution to binding affinities, which might be relevant for the interaction with different receptors (An et al., 2015 ▸). In this context, 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (II), and 2-(4-methylphenyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (III), were also synthesized and their molecular structures analysed with the aim of further understanding their pharmacophore properties, as well their use in the design of materials with specific functions. Moreover, compounds (I)–(III) are characterized by the presence of strong hydrogen-bond acceptor groups but weak hydrogen-bond donors, allowing us to further expand our knowledge of the roles of noncovalent intermolecular forces in crystal engineering and supramolecular chemistry.

areas and their contribution to binding affinities, which might be relevant for the interaction with different receptors (An et al., 2015 ▸). In this context, 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (II), and 2-(4-methylphenyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (III), were also synthesized and their molecular structures analysed with the aim of further understanding their pharmacophore properties, as well their use in the design of materials with specific functions. Moreover, compounds (I)–(III) are characterized by the presence of strong hydrogen-bond acceptor groups but weak hydrogen-bond donors, allowing us to further expand our knowledge of the roles of noncovalent intermolecular forces in crystal engineering and supramolecular chemistry.

Experimental

Instrumental

The uncorrected melting points were measured in open-ended capillary tubes in an Electrothermal apparatus IA 9100. 1H (300.01 MHz) and 13C NMR (75.46 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury-300 spectrometer using CDCl3 as solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal reference; chemical shift values (δ) are in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants (J values) are in Hertz (Hz). IR spectra was obtained with a 3100 FT–IR Excalibur Series spectrophotometer.

Theoretical calculations

Geometry optimizations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory were performed without any symmetry restraints using the GAUSSIAN09 package (Frisch et al., 2009 ▸). Relaxed linear potential energy surface scans for the N1—C10 and C2—C16 rotations were performed using direct inversion of iterative subspace (GDIIS) (Farkas & Schlegel, 2002 ▸).

Synthesis and crystallization

1-(4-Nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (I)

Compound (I) was prepared from benzimidazole (1.00 g, 8.47 mmol) and 1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene (1.19 g, 8.47 mol) in a basic medium of K2CO3 (2.34 g, 16.9 mmol) in dimethyl sulfoxide (13 ml) at 393 K for 20 h, as reported for 2-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-benzimidazole (González-Padilla et al., 2014 ▸). The compound was obtained as a pale-yellow solid in 96% yield (m.p. 453–454 K). Crystals of (I) were obtained after crystallization from an ethanol solution. 1H NMR: δ 8.48 (m, 2H, H-12,14), 8.20 (s, 1H, H-2), 7.92 (m, 1H, H-4), 7.41 (m, 2H, H-5,6), 7.62 (m, 1H, H-7), 7.77 (m, 2H, H-11,15). 13C NMR: δ 146.7 (C-13), 144.6 (C-9), 141.9 (C-10), 141.8 (C-2), 133.0 (C-8), 126.1 (C-12,14), 124.8 (C-6), 124.0 (C5), 123.9 (C-11,15), 121.4 (C-4), 110.5 (C-7). IR (neat, ν, cm1): 1595, 1507 (C=C Ar), 1347 (NO2), 848, 754 (C—H out of plane).

1-(4-Nitrophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (II)

Compound (II) was prepared from 2-phenyl-1H-1,3-benzimidazole (0.216 g, 1.11 mmol) and 1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene (0.157 g, 1.11 mmol) in a basic medium of K2CO3 (0.155 g, 1.11 mmol), dimethylformamide (2 ml) and CuCl (11 mg) as catalyst, as a yellow solid in 72% yield (m.p. 421–423 K). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained from a hexane/ethyl acetate solution. 1H NMR: δ 8.34 (m, 2H, H-12,14), 7.88 (d, 1H, H-4, 3J = 7.6 Hz), 7.48 (m, 4H, H-11,15,17,21), 7.34 (m, 6H, H5-7, 18-20). 13C NMR: δ 152.4 (C2), 147.2 (C9), 143.4 (C13), 142.8 (C10), 136.4 (C8), 130.2 (C19), 129.7 (C16), 129.5 (C18,20), 128.9 (C17), 128.1 (C12,14), 125.5 (C11,15), 124.3 (C6), 124.0 (C5), 120.6 (C4), 110.1 (C7). IR (neat, ν, cm1): 1590, 1526 (C=C Ar), 1350 (NO2), 778, 746, 694 (C—H out of plane).

2-(4-Methylphenyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole, (III)

Compound (III) was prepared from 2-m-tolyl-1H-1,3-benzimidazole (0.300 mg, 1.44 mmol) as a yellow solid in 20% yield after silica-gel chromatography (m.p. 447.7–449.0 K). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained from an hexane/ethyl acetate solution. 1H NMR: δ 8.38 (m, 2H, H-18,20), 7.90 (d, 1H, H-4, 3 J = 7.8 Hz), 7.54 (s, 1H, H15), 7.50 (m, 2H, H-17,21), 7.34 (m, 6H, H5-7, 11-13), 2.34 (s, 3H, Me). 13C NMR: δ 152.7 (C2), 147.2 (C9), 143.4 (C10), 142.8 (C13), 139.0 (C20), 136.3 (C8), 131.1 (C18), 130.5 (C17), 129.3 (C16), 128.6 (C19), 128.1 (C12,14), 126.7 (C21), 125.1 (C11,15), 124.2 (C6), 124.0 (C5), 120.6 (C4), 110.1 (C7), 21.6 (Me). IR (neat, ν, cm1): 1678 (C=N), 1590, 1515 (C=C Ar), 1347, 1303 (NO2), 791, 756, 745, 695 (C—H out of plane).

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1 ▸. H atoms on C atoms were positioned geometrically and treated as riding atoms, with C—H = 0.95–0.99 Å and U iso(H) = 1.5U eq(C) for methyl H atoms or 1.2U eq(C) otherwise.

Table 1. Experimental details.

| (I) | (II) | (III) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | |||

| Chemical formula | C13H9N3O2 | C19H13N3O2 | C20H15N3O2 |

| M r | 239.23 | 315.32 | 329.35 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, C2/c | Triclinic, P

|

Triclinic, P

|

| Temperature (K) | 293 | 100 | 273 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 25.074 (3), 7.1422 (8), 24.283 (3) | 10.2685 (7), 15.1411 (10), 19.4521 (14) | 8.186 (4), 9.806 (4), 11.264 (5) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 96.599 (2), 90 | 91.886 (1), 95.725 (1), 90.118 (1) | 112.825 (7), 98.468 (7), 94.276 (7) |

| V (Å3) | 4319.9 (9) | 3007.6 (4) | 815.6 (6) |

| Z | 16 | 8 | 2 |

| Radiation type | Mo Kα | Mo Kα | Mo Kα |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.30 × 0.28 × 0.24 | 0.38 × 0.34 × 0.32 | 0.40 × 0.30 × 0.25 |

| Data collection | |||

| Diffractometer | Bruker APEXII area detector | Bruker APEXII area detector | Bruker APEXII area detector |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 19923, 3811, 3303 | 16980, 10449, 8103 | 9543, 3787, 3177 |

| R int | 0.047 | 0.029 | 0.022 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.595 | 0.595 | 0.666 |

| Refinement | |||

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.072, 0.153, 1.20 | 0.054, 0.120, 1.05 | 0.050, 0.132, 1.04 |

| No. of reflections | 3811 | 10449 | 3787 |

| No. of parameters | 325 | 865 | 228 |

| H-atom treatment | H-atom parameters constrained | H-atom parameters constrained | H-atom parameters constrained |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.24, −0.27 | 0.26, −0.22 | 0.19, −0.25 |

Results and discussion

Molecular and supramolecular structure of compound (I)

Two independent molecules, i.e. A (atoms N1/C2/N3/C4–C15/N13/O13A/O13B) and B (N21/C22/N23/C24–C35/N33/O33A/O33B), appear in the asymmetric unit of compound (I) (Fig. 1 ▸), which crystallizes in the monoclinic space group C2/c. Molecules (IA) and (IB) are related by a second-order pseudo-helicoidal axis. The nitrobenzene ring (denoted N-nitroBz) is twisted from the mean benzimidazole (Bzm) plane by 35.71 (9) and 40.11 (7)° in molecules (IA) and (IB), respectively (Spek, 2009 ▸). The first value is very close to that observed in 6-methoxy-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,3-benzimidazole (36.15°; Kumar et al., 2013 ▸). The NO2 group is in the plane of the nitrobenzene ring in (IA) [C14—C13—N13—O13B = −2.2 (4)°] and twisted in (IB) [C34—C33—N33—O33B = −22.4 (4)°]. However, the C—NO2 bond lengths are equal in both molecules and are also in the expected range (Allen et al., 1987 ▸), suggesting a limited conjugation between them. The N-nitroBz ring in the reported crystal structures of 1-(4-nitrophenyl)pyrazole and 1-(4-nitrophenyl)pyrrole (Ishihara et al., 1992 ▸) is almost coplanar with the heterocyclic ring. Thus, the observed twist of the N-nitroBz ring from the Bzm plane in compound (I) is the result of steric repulsion between the fused benzene and N-nitroBz rings. This last ring can adopt a perpendicular disposition, in relation to the Bzm heterocycle, similar to those structures with high steric demand such as phenanthroimidazoles (Zhang et al., 2016 ▸).

Figure 1.

(a) The molecular structure of compound (I), with displacement ellipsoids drawn at the 30% probability level. Two independent molecules, i.e. (IA) (atoms N1/C2/N3/C4–C15/N13/O13A/O13B) and (IB) (N21/C22/N23/C24-C35/N33/O33A/O33B), are present in the asymmetric unit. (b) A view of rotamers (IA) and (IB) along the N13⋯N3 and N33⋯N23 imaginary axes, respectively.

Soft Csp

2—H⋯O interactions give shape to the crystal packing, with the participation of a nitro O atom, as the acceptor, in a monocoordination fashion (Allen et al., 1997 ▸). Two (IA) molecules form centrosymmetric dimers, i.e.

A

2, through C12—H12⋯O13A

i interactions, describing a twisted  (10) motif (Bernstein et al., 1995 ▸) (Fig. 2 ▸

a). Furthermore, a meso helix is developed along the [030] direction through C7—H7⋯Cg2v T-shaped interactions linking the A

2 dimers [Cg2 is the centroid of the C4–C9 ring; symmetry code: (v) −x +

(10) motif (Bernstein et al., 1995 ▸) (Fig. 2 ▸

a). Furthermore, a meso helix is developed along the [030] direction through C7—H7⋯Cg2v T-shaped interactions linking the A

2 dimers [Cg2 is the centroid of the C4–C9 ring; symmetry code: (v) −x +  , y −

, y −  , −z +

, −z +  ]. (IB) molecules self-associate into C(11) chains through C24—H24⋯O33B

iii interactions, which propagate within the (

]. (IB) molecules self-associate into C(11) chains through C24—H24⋯O33B

iii interactions, which propagate within the ( ,1,11) and (

,1,11) and ( ,

, ,11) families of planes. A and B molecules of compound (I) are connected through C15—H15⋯O33A

ii interactions. Chains of (IB) running in the [

,11) families of planes. A and B molecules of compound (I) are connected through C15—H15⋯O33A

ii interactions. Chains of (IB) running in the [ ,1,11] direction and n molecules of (IB), each belonging to an infinite number of (IB) chains running within the (

,1,11] direction and n molecules of (IB), each belonging to an infinite number of (IB) chains running within the ( ,

, ,11) family of planes, are linked to A

2 helices, forming the M and P strands BnnA

2

nB. The second dimension is given by the interlinkage of the strands through C35—H35⋯O13A

iv interactions (Figs. 2 ▸

b and 2c). The geometric features and symmetry codes associated with these interactions are listed in Table 2 ▸. Molecule (IB) displays a twist of 22.4 (4)° of the NO2 group, which is comparable to that seen in high-energy molecules such as TNT (Landenberger & Matzger, 2010 ▸). This torsion, together with an N-nitroBz torsion of 40.11 (7)° from the Bzm plane, favour the helical arrangement of (I) in the solid (Ramírez-Milanés et al., 2017 ▸).

,11) family of planes, are linked to A

2 helices, forming the M and P strands BnnA

2

nB. The second dimension is given by the interlinkage of the strands through C35—H35⋯O13A

iv interactions (Figs. 2 ▸

b and 2c). The geometric features and symmetry codes associated with these interactions are listed in Table 2 ▸. Molecule (IB) displays a twist of 22.4 (4)° of the NO2 group, which is comparable to that seen in high-energy molecules such as TNT (Landenberger & Matzger, 2010 ▸). This torsion, together with an N-nitroBz torsion of 40.11 (7)° from the Bzm plane, favour the helical arrangement of (I) in the solid (Ramírez-Milanés et al., 2017 ▸).

Figure 2.

The two-dimensional supramolecular architecture of compound (I), built up by C—H⋯O interactions. (a) Dimers A 2 and tapes Bn are shown. (b) The M and P strands formed by the interlinkage of tapes, and helices BnnA 2 nB. (c) Dispersive interactions ONO⋯Cg, Cg⋯Cg and ONO⋯C2, giving rise to the three-dimensional network of compound (I).

Table 2. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (I) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12—H12⋯O13A i | 0.93 | 2.45 | 3.350 (4) | 164 |

| C15—H15⋯O33A ii | 0.93 | 2.59 | 3.515 (4) | 173 |

| C24—H24⋯O33B iii | 0.93 | 2.55 | 3.375 (4) | 149 |

| C35—H35⋯O13A iv | 0.93 | 2.64 | 3.281 (4) | 127 |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  ; (iii)

; (iii)  ; (iv)

; (iv)  .

.

The three-dimensional structure is developed by nitro–π and π– dispersive interactions, viz. the nitro group of molecule (IA) to the centroid of the heterocyclic ring of molecule (IB), i.e. N13⋯O13B⋯Cg5vi [O13B⋯Cg5 = 3.346 (3) Å, N13⋯Cg5 = 3.431 (3) Å and N13⋯O13B⋯Cg5 = 83.68 (19)°; Cg5 is the centroid of the N21/C22/N23/C29/C28 ring; symmetry code: (vi) x −

dispersive interactions, viz. the nitro group of molecule (IA) to the centroid of the heterocyclic ring of molecule (IB), i.e. N13⋯O13B⋯Cg5vi [O13B⋯Cg5 = 3.346 (3) Å, N13⋯Cg5 = 3.431 (3) Å and N13⋯O13B⋯Cg5 = 83.68 (19)°; Cg5 is the centroid of the N21/C22/N23/C29/C28 ring; symmetry code: (vi) x −  , y −

, y −  , z], and Cg2⋯Cg7v, between the aromatic ring (Cg2 is the centroid of the C4—C9 ring and Cg7 is the centroid of the C30–C35 ring) of the Bzm moiety of molecule (IA) and the nitrobenzene ring of molecule (IB). The intercentroid Cg2⋯Cg7v distance [3.6123 (17) Å] is very close to the interplanar distance [3.4361 (12) Å], in agreement with a face-to-face interaction (García-Báez et al., 2003 ▸). It is worth mentioning that the calculated value of the gas-phase binding energy of π–

, z], and Cg2⋯Cg7v, between the aromatic ring (Cg2 is the centroid of the C4—C9 ring and Cg7 is the centroid of the C30–C35 ring) of the Bzm moiety of molecule (IA) and the nitrobenzene ring of molecule (IB). The intercentroid Cg2⋯Cg7v distance [3.6123 (17) Å] is very close to the interplanar distance [3.4361 (12) Å], in agreement with a face-to-face interaction (García-Báez et al., 2003 ▸). It is worth mentioning that the calculated value of the gas-phase binding energy of π– stacking has been reported as −6.7 kcal mol−1 (1 kcal mol−1 = 4.184 kJ mol−1) between phenylalanine and nitrobenzene (An et al., 2015 ▸), pointing to the relevance of this interaction in the crystal lattice arrangement.

stacking has been reported as −6.7 kcal mol−1 (1 kcal mol−1 = 4.184 kJ mol−1) between phenylalanine and nitrobenzene (An et al., 2015 ▸), pointing to the relevance of this interaction in the crystal lattice arrangement.

In addition, an intermolecular NO2⋯Csp 2 interaction is observed between a nitro O atom as donor and the C2 atom of the NCN fragment of the heterocyclic Bzm ring. The geometric parameters associated with this last n–π* interaction are O33B⋯C2vii = 3.213 (3) Å and N33⋯O33B⋯C2 = 93.7 (2)° [symmetry code: (vii) x, y − 1, z] (Fig. 2 ▸ c). This interaction has been described in 3,3′-dinitro-2,2′-bipyridine N-oxides, with distances in the range 2.762 (4)–2.789 (3) Å (O’Leary & Wallis, 2007 ▸), clearly shorter than in (I) because of its intramolecular nature. Additionally, an analogous interaction of the nitrile group with the C2 atom of the Bzm ring, CN⋯Csp 2, occurred in (Z)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-(1-phenyl-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile (Hranjec et al., 2012 ▸).

Molecular and supramolecular structure of compound (II)

Compound (II) crystallizes in the triclinic space group P

, with four independent molecules in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 3 ▸), namely (IIA) (atoms N1/C2/N3/C4–C15/N13/O13A/O13B), (IIB) (N21/C22/N23/C24–C35/N33/O33A/O33B), (IIC) (N41/C42/N43/C44–C55/N53/O53A/O53B) and (IID) (N61/C62/N63/C64–C75/N73/O73A/O73B). Molecules (IIA) and (IIC), as well as (IIB) and (IID), are related by a local pseudocentre of inversion located at the fractional coordinates (0.276, 0.376, 0.626) and (0.272, 0.876, 0.626), respectively, in the asymmetric unit. This condition has frequently been observed in P

, with four independent molecules in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 3 ▸), namely (IIA) (atoms N1/C2/N3/C4–C15/N13/O13A/O13B), (IIB) (N21/C22/N23/C24–C35/N33/O33A/O33B), (IIC) (N41/C42/N43/C44–C55/N53/O53A/O53B) and (IID) (N61/C62/N63/C64–C75/N73/O73A/O73B). Molecules (IIA) and (IIC), as well as (IIB) and (IID), are related by a local pseudocentre of inversion located at the fractional coordinates (0.276, 0.376, 0.626) and (0.272, 0.876, 0.626), respectively, in the asymmetric unit. This condition has frequently been observed in P

crystals of high-Z′ structures (Desiraju, 2007 ▸). The N-nitroBz and C2-Ph rings are both twisted from the mean Bzm plane; the angles between the planes of the Bzm, N-nitroBz and C2-Ph rings are listed in Table 3 ▸. In spite of their inherent crystallographic differences, molecules (IIA) and (IIB) have similar angles, as have molecules (IIC) and (IID), judged by the mean values of the angles between the planes. The N-nitroBz ring in compound (II) deviates more from coplanarity with the Bzm ring than the C2-Ph ring, but within the range found for 1,2-diphenylbenzimidazole compounds (González-Padilla et al., 2014 ▸) and 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-phenylimidazole (Ishihara et al., 1992 ▸).

crystals of high-Z′ structures (Desiraju, 2007 ▸). The N-nitroBz and C2-Ph rings are both twisted from the mean Bzm plane; the angles between the planes of the Bzm, N-nitroBz and C2-Ph rings are listed in Table 3 ▸. In spite of their inherent crystallographic differences, molecules (IIA) and (IIB) have similar angles, as have molecules (IIC) and (IID), judged by the mean values of the angles between the planes. The N-nitroBz ring in compound (II) deviates more from coplanarity with the Bzm ring than the C2-Ph ring, but within the range found for 1,2-diphenylbenzimidazole compounds (González-Padilla et al., 2014 ▸) and 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-phenylimidazole (Ishihara et al., 1992 ▸).

Figure 3.

The molecular structure of compound (II), with displacement ellipsoids drawn at the 30% probability level. Four independent molecules are present in the asymmetric unit, namely A (atoms N1/C2/N3/C4–C15/N13/O13A/O13B), B (N21/C22/N23/C24–C35/N33/O33A/O33B), C (N41/C42/N43/C44–C55/N53/O53A/O53B) and D (N61/C62/N63/C64–C75/N73/O73A/O73B).

Table 3. Experimental angles (°) between the planes of the Bzm, N-nitroPh and C2-Ph rings in molecules A–D of compound (II) .

| Planes | Angles (°) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | (IIA) | (IIB) | Mean value | (IIC) | (IID) | Mean value |

| (IIA) and (IIB) | (IIC) and (IID) | ||||||

| Bzm | N-nitroBz | 54.20 (5) | 54.40 (5) | 54.30 (7) | 60.47 (5) | 58.02 (5) | 59.25 (7) |

| Bzm | C2-Ph | 29.05 (6) | 29.10 (6) | 29.08 (8) | 31.22 (6) | 32.74 (6) | 26.98 (8) |

| N-nitroBz | C2-Ph | 58.65 (5) | 59.16 (5) | 58.91 (7) | 68.44 (6) | 66.70 (5) | 67.57 (8) |

Molecules (IIA) and (IIB) are linked through N⋯NO2 interactions (N13⋯N23 and N33⋯N3), with the participation of the pyridine-like N atom as the donor and the N atom of the nitro group as the acceptor, forming  (16) chains propagating along the b axis. Chains of (IIA) and (IIB) molecules are linked through C6—H6⋯O13A

i and C26—H26⋯O33B

iv soft hydrogen bonds to develop a sheet within the ab plane. C7—H7⋯O33B

ii and C27—H27⋯O13A

v soft hydrogen bonds are responsible for linking two (IIA)/(IIB) planes along the c-axis direction, i.e. (A

2

B

2)n (Fig. 4 ▸

a). These C—H⋯O interactions are of the bifurcated type with respect to the acceptor O atoms, i.e. H6⋯O13A⋯H27 and H7⋯O33B⋯H26. The geometrical parameters and symmetry codes of the hydrogen-bonding and N⋯NO2 interactions are listed in Tables 4 ▸ and 5 ▸, respectively.

(16) chains propagating along the b axis. Chains of (IIA) and (IIB) molecules are linked through C6—H6⋯O13A

i and C26—H26⋯O33B

iv soft hydrogen bonds to develop a sheet within the ab plane. C7—H7⋯O33B

ii and C27—H27⋯O13A

v soft hydrogen bonds are responsible for linking two (IIA)/(IIB) planes along the c-axis direction, i.e. (A

2

B

2)n (Fig. 4 ▸

a). These C—H⋯O interactions are of the bifurcated type with respect to the acceptor O atoms, i.e. H6⋯O13A⋯H27 and H7⋯O33B⋯H26. The geometrical parameters and symmetry codes of the hydrogen-bonding and N⋯NO2 interactions are listed in Tables 4 ▸ and 5 ▸, respectively.

Figure 4.

The supramolecular architecture of compound (II). (a) The interlinkage of  (16) chains propagating along the b axis developing the two-dimensional arrangement of molecules (IIA) and (IIB) in the ab plane. (b) Ribbons of (IIC)/(IID) developing along the b axis; the (IID) molecule with symmetry code (x, y, z) is not shown for clarity. (c) (DC

2

D)n ribbons within the bc plane.

(16) chains propagating along the b axis developing the two-dimensional arrangement of molecules (IIA) and (IIB) in the ab plane. (b) Ribbons of (IIC)/(IID) developing along the b axis; the (IID) molecule with symmetry code (x, y, z) is not shown for clarity. (c) (DC

2

D)n ribbons within the bc plane.

Table 4. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (II) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6—H6⋯O13A i | 0.95 | 2.52 | 3.298 (3) | 139 |

| C7—H7⋯O33B ii | 0.95 | 2.54 | 3.357 (3) | 145 |

| C15—H15⋯O53B iii | 0.95 | 2.61 | 3.468 (3) | 151 |

| C26—H26⋯O33B iv | 0.95 | 2.52 | 3.302 (3) | 140 |

| C27—H27⋯O13A v | 0.95 | 2.53 | 3.355 (3) | 145 |

| C35—H35⋯O73B v | 0.95 | 2.64 | 3.527 (3) | 156 |

| C44—H44⋯O73A v | 0.95 | 2.66 | 3.309 (3) | 126 |

| C52—H52⋯O53A vi | 0.95 | 2.46 | 3.299 (3) | 148 |

| C54—H54⋯N3vii | 0.95 | 2.47 | 3.412 (3) | 171 |

| C55—H55⋯O33A iv | 0.95 | 2.33 | 3.184 (3) | 149 |

| C64—H64⋯O53A viii | 0.95 | 2.51 | 3.227 (3) | 132 |

| C74—H74⋯N23v | 0.95 | 2.50 | 3.437 (3) | 167 |

| C75—H75⋯O13B v | 0.95 | 2.34 | 3.217 (3) | 153 |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  ; (iii)

; (iii)  ; (iv)

; (iv)  ; (v)

; (v)  ; (vi)

; (vi)  ; (vii)

; (vii)  ; (viii)

; (viii)  .

.

Table 5. N⋯NO2 geometric parameters (Å, °) for (II).

| C—N⋯N | N⋯N | C—N⋯N |

|---|---|---|

| C13—N13⋯N23ix | 3.050 (2) | 88.49 (19) |

| C33—N33⋯N3x | 3.053 (2) | 88.33 (19) |

| C53⋯N53⋯N63viii | 3.102 (2) | 90.58 (19) |

| C73⋯N73⋯N43v | 3.134 (2) | 91.59 (19) |

Symmetry codes: (v) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 1; (viii) −x + 1, −y, −z + 1; (ix) x, y, z; (x) x, y − 1, z.

Molecules (IIC) and (IID) develop a (DC

2

D)n ribbon within the (10 ) family of planes (Figs. 4 ▸

b and 4c), also through N⋯NO2 and C—H⋯O interactions (N63⋯N53viii, N43⋯N73v, C44—H44⋯O73A

i, C64—H64⋯O53A

viii and C52—H52⋯O53A

vi). The (A

2

B

2)n double sheets and (DC

2

D)n ribbons are interleaved to develop the three-dimensional structure along the c-axis direction through C—H⋯X (X = N and O) interactions (C54—H54⋯N3vii, C74—H74⋯N23v, C15—H15⋯O53B

iii, C35—H35⋯O73B

v, C55—H55⋯O33A

iv and C75—H75⋯O13B

v), with the participation of the pyridine-like N and nitro O atoms as acceptors.

) family of planes (Figs. 4 ▸

b and 4c), also through N⋯NO2 and C—H⋯O interactions (N63⋯N53viii, N43⋯N73v, C44—H44⋯O73A

i, C64—H64⋯O53A

viii and C52—H52⋯O53A

vi). The (A

2

B

2)n double sheets and (DC

2

D)n ribbons are interleaved to develop the three-dimensional structure along the c-axis direction through C—H⋯X (X = N and O) interactions (C54—H54⋯N3vii, C74—H74⋯N23v, C15—H15⋯O53B

iii, C35—H35⋯O73B

v, C55—H55⋯O33A

iv and C75—H75⋯O13B

v), with the participation of the pyridine-like N and nitro O atoms as acceptors.

Remarkably, the intermolecular Npy⋯NO2 (n–π*) interaction plays a crucial role in the molecular self-assembly and crystal packing of compound (II). The nitro N atoms have been observed to interact with electron-rich centres, such as an O atom of another nitro group (Daszkiewicz, 2013 ▸), the N atom of a dimethylamino group in perinaphthalenes (Egli et al., 1986 ▸; Ciechanowicz-Rutkowska, 1977 ▸) and the pyridine-like N atom of azole compounds (Yap et al., 2005 ▸). The geometric parameters of the intermolecular N⋯NO2 interactions in (II) are similar to the values found in the crystal structure of 2-methyl-4,6-dinitro-1-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)benzimidazole (Freyer et al., 1992 ▸), with N⋯N = 3.089 Å and C⋯N⋯N = 95.4°.

The NO2⋯Csp 2 and Npy⋯NO2 interactions present in (I) and (II), respectively, are of the orthogonal n–π* type, since the donor atom approaches in a perpendicular manner to the plane that includes the acceptor. N⋯NO2 interactions have been envisaged as an entry to supramolecular cages without using metals to make orthogonal corners (Yap et al., 2005 ▸).

The crystal structure of compound (II) is an example of a compound with many symmetry-independent molecules in the asymmetric unit. This phenomenon has been extensively analysed elsewhere (Bernstein et al., 2008 ▸). The introduction of a C2-Ph ring in compound (II) to the already present N-nitroBz ring in (I) is expected to increase the rotational barrier of the latter, reducing the possibilities of conformational isomers. Nevertheless, the effect is the opposite and contrasts with similar structures lacking the nitro group, such as 1-phenyl-2-p-tolyl-1H-benzimidazole (Mohandas et al., 2013 ▸) and 1,2-diphenyl-1H-benzimidazole (Rosepriya et al., 2012 ▸), or those containing a nitro group, 6-ethyl-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-benzimidazole (Kumar & Punniyamurthy, 2012 ▸), but having steric constraints. All of them only have one molecule in the asymmetric unit.

Molecular and supramolecular structure of compound (III)

Compound (III) crystallizes in the triclinic space group P

, with one molecule in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 5 ▸

a). Both N-nitroBz and C2-MeBz rings are twisted from the mean Bzm plane, the angles between the planes being 67.74 (4) (Bzm and N-nitroBz), 28.21 (5) (Bzm and C2-MeBz) and 64.77 (5)° (N-nitroBz and C2-MeBz), i.e. more twisted than in compound (II). The NO2 group is almost in the plane of the N-nitroBz ring [C14—C13—N13—O13B = 6.9 (2)°].

, with one molecule in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 5 ▸

a). Both N-nitroBz and C2-MeBz rings are twisted from the mean Bzm plane, the angles between the planes being 67.74 (4) (Bzm and N-nitroBz), 28.21 (5) (Bzm and C2-MeBz) and 64.77 (5)° (N-nitroBz and C2-MeBz), i.e. more twisted than in compound (II). The NO2 group is almost in the plane of the N-nitroBz ring [C14—C13—N13—O13B = 6.9 (2)°].

Figure 5.

(a) The molecular structure of compound (III), with displacement ellipsoids drawn at the 30% probability level. The supramolecular structure as (b) zero-dimensional, (c) one-dimensional, and (d) two- and three-dimensional.

Molecules of (III) are self-assembled in pairs through C11—H11⋯N3i interactions in the form of an  (12) ring (Fig. 5 ▸

b). Infinite tapes propagating along the a-axis direction are developed by C12—H12⋯N3ii soft hydrogen bonds, forming an

(12) ring (Fig. 5 ▸

b). Infinite tapes propagating along the a-axis direction are developed by C12—H12⋯N3ii soft hydrogen bonds, forming an  (10) ring motif (Fig. 5 ▸

c). Finally, the two- and three-dimensional structures are arranged through C14—H14⋯Cg2iii and N13—O13A⋯Cg3iv dispersive interactions [O13A⋯Cg3iv = 3.254 (2) Å and N13⋯O13A⋯Cg3 = 94.12 (11)°; Cg2 is the centroid of the C4–C9 ring and Cg3 is the centroid of the C10–C15 ring; symmetry codes: (iii) −x, −y + 1, −z; (iv) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 2] (Fig. 5 ▸

d). The geometrical parameters and symmetry codes of the hydrogen bonding for compound (III) are listed in Table 6 ▸.

(10) ring motif (Fig. 5 ▸

c). Finally, the two- and three-dimensional structures are arranged through C14—H14⋯Cg2iii and N13—O13A⋯Cg3iv dispersive interactions [O13A⋯Cg3iv = 3.254 (2) Å and N13⋯O13A⋯Cg3 = 94.12 (11)°; Cg2 is the centroid of the C4–C9 ring and Cg3 is the centroid of the C10–C15 ring; symmetry codes: (iii) −x, −y + 1, −z; (iv) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 2] (Fig. 5 ▸

d). The geometrical parameters and symmetry codes of the hydrogen bonding for compound (III) are listed in Table 6 ▸.

Table 6. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (III) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11—H11⋯N3i | 0.93 | 2.66 | 3.431 (2) | 141 |

| C12—H12⋯N3ii | 0.93 | 2.47 | 3.348 (2) | 157 |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Calculated molecular structures of compounds (I)–(III)

Ab initio theoretical density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory were performed to support the experimental findings. The calculated geometric parameters are in agreement with the experimental ones. In general, the differences between the geometrical parameters in the experimental and optimized geometries are in most cases 0.01 Å (bond lengths) and 0.5° (bond angles), but large differences are observed for torsion angles that might be attributed to the gas-phase calculations without considering the crystal-packing forces. Additionally, the greater differences in favour of the N-nitroBz ring might be attributed to the presence of the nitro group, which is involved in intermolecular interactions.

The nitro group retrieves electronic density from the benzene ring, so the Csp 2—H hydrogens bear a significant positive charge, particularly H12 and H14, which are both in ortho positions with respect to the nitro group. The calculated MKS charges are listed in Table 7 ▸. These H atoms lead to the formation of the hydrogen-bonding network in compound (I). The n–π* donor–acceptor interactions ONO⋯Csp 2 and Npy⋯NO2 observed in (I) and (II), respectively, are charge assisted. In both molecules, the N atom of the nitro group bears the most positive charge, followed by the C atom of the NCN fragment in the heterocyclic ring. In contrast, the pyridine-like N atom (Npy) of the heterocycle bears the most negative charge, followed by the O atoms of the nitro group. The C2-Ph substitution in compound (II) has the effect of increasing the absolute value of the charges in the NCN fragment with the concomitant diminution of the dipolar moment [2.32 Debye in (I) to 1.84 Debye in (II)].

Table 7. Selected MKS charges calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory for compounds (I)–(III).

| MKS charge | MKS charge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom | (I) | (II) | (III) | Atom | (I) | (II) | (III) |

| N1 | −0.183 | −0.324 | −0.409 | H4 | 0.183 | 0.172 | 0.164 |

| C2 | 0.277 | 0.473 | 0.531 | H6 | 0.142 | 0.133 | 0.133 |

| N3 | −0.597 | −0.621 | −0.541 | H7 | 0.146 | 0.147 | 0.142 |

| C10 | 0.185 | 0.303 | 0.359 | H12 | 0.156 | 0.161 | 0.165 |

| N13 | 0.661 | 0.648 | 0.659 | H14 | 0.163 | 0.171 | 0.177 |

| O13A | −0.394 | −0.392 | −0.396 | H11 | 0.133 | 0.148 | 0.155 |

| O13B | −0.394 | −0.389 | −0.393 | H15 | 0.137 | 0.128 | 0.131 |

The theoretical energy profiles of compounds (I)–(III) were also calculated to estimate the energy involved in the interconversion between the N-nitroBz and C2-Ph rotamers. The experimental and theoretical torsion-angle values are listed in Table 8 ▸. The calculated most-stable rotamer of compound (I) is similar to that adopted by molecule (IA) in the crystal lattice, where the N-nitroBz ring is twisted from the mean Bz plane, with a C8—N1—C10—C11 torsion angle of −39.43 (calculated) versus −32.47° (experimental). The maximum energy values of 3.27 or 2.10 kcal mol−1 were found when the N-nitroBz ring is coplanar or perpendicular to the benzimidazole heterocycle, respectively. Because of symmetry reasons and the small cost in energy, the calculated rotamer with a C8—N1—C10—C11 torsion angle of 39.43° is equally probable (see Fig. S1 in the supporting information). The rotational barriers of compounds (I)–(III) are listed in Table S1 in the supporting information.

Table 8. Experimental and theoretically calculated torsion angles (°) in compounds (I)–(III).

| Molecule | (I) | (II) | (III) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C8—N1—C10—C11 | Calculated | −39.43 | 58.60 | 58.72 |

| C8—N1—C10—C11 | A | −32.47 | −59.16 | 72.23 (19) |

| C28—N21—C30—C31 | B | 38.81 | 59.18 | |

| C48—N41—C50—C51 | C | 63.54 | ||

| C68—N61—C70—C71 | D | 60.94 | ||

| N1—C2—C16—C17 | Calculated | 33.73 | 33.31 | |

| N1—C2—C16—C17 | A | −29.19 | 29.5 (2) | |

| N21—C22—C36—C37 | B | 29.69 | ||

| N41—C42—C56—C57 | C | 29.99 | ||

| N61—C62—C76—C77 | D | 32.26 |

In the case of compound (II), the calculated C8—N1—C10—C11 and N1—C2—C16—C17 torsion angles of 58.60 and 33.73°, respectively, are in close correspondence with the mean absolute value of the four molecules (IIA)–(IID) found in the asymmetric unit (60.7±2.1 and 30.3±1.4°, respectively). The N1—C2—C16—C17 torsion angle was fixed at 33.73° to calculate the rotational barrier of the N-nitroBz ring. A maximum peak of energy 8.95 kcal mol−1 was found when the N-nitroBz ring is in the same plane as the Bz heterocycle and of only 1.60 kcal mol−1 when perpendicular (Fig. 6 ▸). Thus, the steric effect of the C2-Ph ring increases by 2.7-fold the energy required to rotate the N-nitroBz ring. The rotational barrier of the C2-Ph ring was calculated by fixing the C8—N1—C10—C11 torsion angle at 58.60°. Two energy maxima were found when the C2-Ph ring is perpendicular to or coplanar with the benzimidazole plane, with values of 3.60 and 0.99 kcal mol−1, respectively (see Fig. S2 in the supporting information). Therefore, the rotational barrier of the C2-Ph ring is just 40% of the energy required to rotate the N-nitroBz ring.

Figure 6.

Theoretical rotation profile of the C8—N1—C10—C11 torsion angle in compound (II). The Bzm heterocycle in shown in blue, the N-nitroBz ring in red and the C2-Ph ring in green.

The calculated C8—N1—C10—C11 torsion angle of 58.72° contrasts with the experimental value of 72.23 (19)° for compound (III). This difference could be explained because of C11—H11⋯N3 hydrogen bonding to form the already described self-paired structure (vide supra). However, the energy profile and the maximum peak of energy 9.20 kcal mol−1 were found to be very similar to those exhibited by compound (II), in agreement with a negligible steric effect from the methyl group (see Figs. S3 and S4 in the supporting information).

In summary, compounds (I)–(III) are nonplanar molecules having two strong hydrogen-bonding acceptors groups, i.e. an electron-withdrawing nitro group at one end and an electron-donating amino group at the other end. However, the structures lack strong hydrogen-bond donors. Thus, the crystal networks are developed by dispersive soft interactions, with the participation of the nitro group, namely Csp

2—H⋯ONO,  –π and n–π* (n = O and Npy; π* = Csp

2 and

–π and n–π* (n = O and Npy; π* = Csp

2 and  ) interactions (Fig. 7 ▸).

) interactions (Fig. 7 ▸).

Figure 7.

Pictorial representations of several interactions of the nitro group in the supramolecular architecture of compounds (I)–(III), showing nitro–π* (left), and π–π* and N⋯NO2 (right). The θ angles are around 90°

Theoretical calculations confirmed that the presence of the C2-Bz ring increases the rotational barrier of the N-nitroBz ring, thus fewer conformers are expected. However, compound (II) is a high Z′-structure where equi-energetic conformers co-exist in the crystal network. Calculations also supported the fact that orthogonal ONO⋯Csp

2 and Npy⋯ interactions are assisted by electrostatic attraction. The study of these molecules bearing the benzimidazole pharmacophore and nitroarenes would address the issues related to the steric and geometrical preferences for the occurrence of molecular aggregation through nitro-group interactions with important pharmacological protein targets and the development of new materials. In this regard, a family of nitroarene–benzimidazole compounds are under investigation as COX inhibitors by our research group.

interactions are assisted by electrostatic attraction. The study of these molecules bearing the benzimidazole pharmacophore and nitroarenes would address the issues related to the steric and geometrical preferences for the occurrence of molecular aggregation through nitro-group interactions with important pharmacological protein targets and the development of new materials. In this regard, a family of nitroarene–benzimidazole compounds are under investigation as COX inhibitors by our research group.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I, II, III, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146Isup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) II. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146IIsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) III. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146IIIsup4.hkl

Theoretical rotation profiles and calculated rotation barriers. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146sup5.pdf

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Herbert Höpfl for the access to the diffractometer.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología grant 255354. Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado, Instituto Politécnico Nacional grant 20164784. Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado, Instituto Politécnico Nacional grant 20170504.

References

- Allen, F. H., Bird, C. M., Rowland, R. S. & Raithby, P. R. (1997). Acta Cryst. B53, 696–701.

- Allen, F. H., Kennard, O., Watson, D. G., Brammer, L., Orpen, A. G. & Taylor, R. (1987). J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, pp. S1–S19.

- An, Y., Bloom, J. W. G. & Wheeler, S. E. (2015). J. Phys. Chem. B, 119, 14441–14450. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J., Davis, R. E., Shimoni, L. & Chang, N.-L. (1995). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 34, 1555–1573.

- Bernstein, J., Dunitz, J. D. & Gavezzotti, A. (2008). Cryst. Growth Des. 8, 2011–2018.

- Bruker (2004). APEX2 and SAINT. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Candeias, N. R., Branco, L. C., Gois, P. M. P., Afonso, C. A. M. & Trindade, A. F. (2009). Chem. Rev 109, 2703–2802. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L. C. R., Fernandes, E. & Marques, M. M. B. (2011). Chem. Eur. J 17, 12544–12555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ciechanowicz-Rutkowska, M. (1977). J. Solid State Chem. 22, 185–192.

- Daszkiewicz, M. (2013). CrystEngComm, 15, 10427–10430.

- Desiraju, G. R. (2007). CrystEngComm, 9, 91–92.

- Egli, M., Wallis, J. D. & Dunitz, J. D. (1986). Helv. Chim. Acta, 69, 255–266.

- Elias, R. S., Sadiq, M.-H., Ismael, S. M.-H. & Saeed, B. A. (2011). Int. J. PharmTech Res. 3, 2183–2189.

- Farkas, O. & Schlegel, H. B. (2002). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 4, 11–15.

- Farrugia, L. J. (2012). J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 849–854.

- Freyer, A. J., Lowe-Ma, C. K., Nissan, R. A. & Wilson, W. S. (1992). Aust. J. Chem. 45, 525–539.

- Frisch, M. J., et al. (2009). GAUSSIAN09. Revision E.01. Gaussian Inc., Wallingford, CT, USA. http://www.gaussian.com

- García-Báez, E. V., Martínez-Martínez, F. J., Höpfl, H. & Padilla-Martínez, I. I. (2003). Cryst. Growth Des. 3, 35–45.

- González-Padilla, J. E., Rosales-Hernández, M. C., Padilla-Martínez, I. I., García-Báez, E. V., Rojas-Lima, S. & Salazar-Pereda, V. (2014). Acta Cryst. C70, 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A. & Rawat, S. (2010). J. Curr. Pharm. Res. 3, 13–23.

- Horton, D. A., Bourne, G. T. & Smythe, M. L. (2003). Chem. Rev. 103, 893–930. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hranjec, M., Horak, E., Tireli, M., Pavlovic, G. & Karminski-Zamola, G. (2012). Dyes Pigm. 95, 644–656.

- Ishihara, M., Tonogaki, M., Ohba, S., Saito, Y., Okazaki, M., Katoh, T. & Kamiyama, K. (1992). Acta Cryst. C48, 184–188.

- Katritzky, A. R., Dobchev, D. A., Fara, D. C. & Karelson, M. (2005). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13, 6598–6608. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Keri, R. S., Hiremathad, A., Budagumpi, S. & Nagaraja, B. M. (2015). Chem. Biol. Drug Des 86, 19–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. V. (2004). Asian J. Chem 16, 1241–1260.

- Kumar, R. K., Manna, S., Mahesh, D., Sar, D. & Punniyamurthy, T. (2013). Asian J. Org. Chem. 2, 843.

- Kumar, R. K. & Punniyamurthy, T. (2012). RSC Advances, 2, 4616–4619.

- Landenberger, K. B. & Matzger, A. J. (2010). Cryst. Growth Des. 10, 5341–5347.

- Macrae, C. F., Bruno, I. J., Chisholm, J. A., Edgington, P. R., McCabe, P., Pidcock, E., Rodriguez-Monge, L., Taylor, R., van de Streek, J. & Wood, P. A. (2008). J. Appl. Cryst. 41, 466–470.

- Mohandas, T., Jayamoorthy, K., Sakthivel, P. & Jayabharathi, J. (2013). Acta Cryst. E69, o334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, J. & Wallis, J. D. (2007). CrystEngComm, 9, 941–950.

- Ramírez-Milanés, E. G., Martínez-Martínez, F. J., Magaña-Vergara, N. E., Rojas-Lima, S., Avendaño-Jiménez, Y. A., García-Báez, E. V., Morín-Sánchez, L. M. & Padilla-Martínez, I. I. (2017). Cryst. Growth Des. 17, 2513–2528.

- Rosepriya, S., Thiruvalluvar, A., Jayamoorthy, K., Jayabharathi, J., Öztürk Yildirim, S. & Butcher, R. J. (2012). Acta Cryst. E68, o3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sabat, M., VanRens, J. C., Laufersweiler, M. J., Brugel, T. A., Maier, J., Golebiowski, A., Easwaran, B. De V., Hsieh, L. C., Walter, R. L., Mekel, M. J., Evdokimov, A. & Janusz, M. J. (2006). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 5973–5977. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Secci, D., Bolasco, A., D’Ascenzio, M., Sala, F., Yáñez, M. & Carradori, S. (2012). J. Heterocycl. Chem 49, 1187–1195.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Spek, A. L. (2009). Acta Cryst. D65, 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yap, G. P. A., Jove, F. A., Claramunt, R. M., Sanz, D., Alkorta, I. & Elguero, J. (2005). Aust. J. Chem. 58, 817–822.

- Zhang, Y., Wang, J.-H., Han, G., Lu, F. & Tong, Q.-X. (2016). RSC Advances, 6, 70800–70809.

- Zhong, C., He, J., Xue, C. & Li, Y. A. (2004). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12, 4009–4015. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I, II, III, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146Isup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) II. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146IIsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) III. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146IIIsup4.hkl

Theoretical rotation profiles and calculated rotation barriers. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229618003406/uk3146sup5.pdf