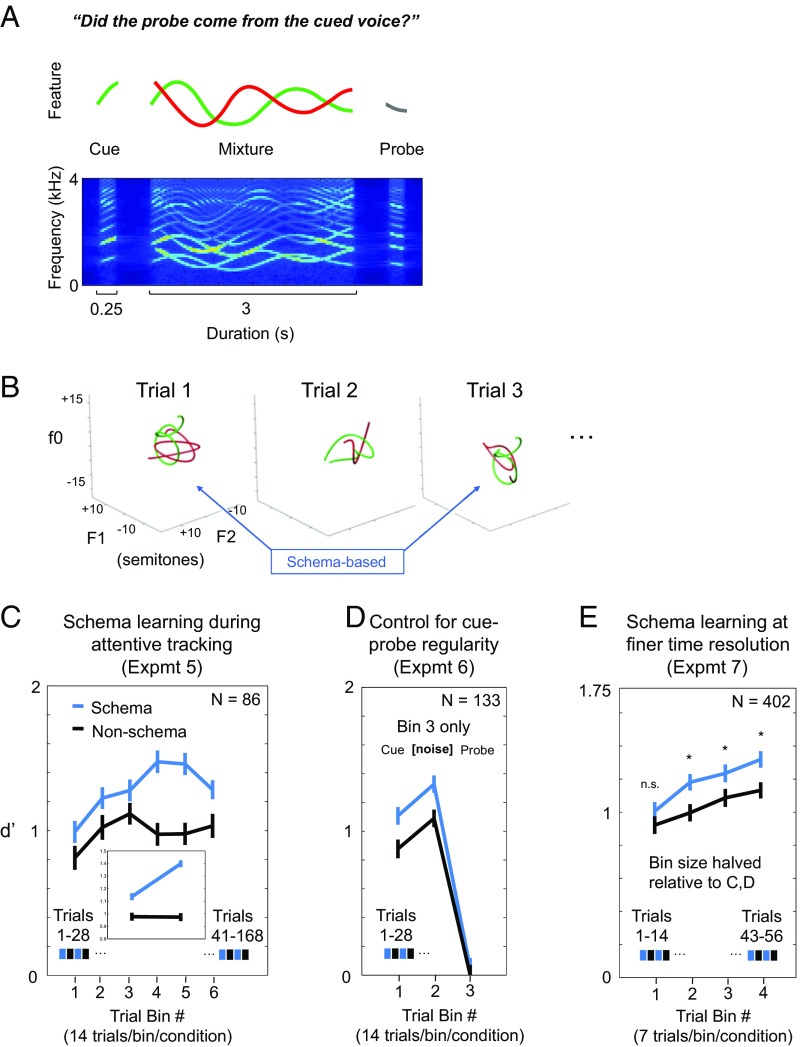

Fig. 2.

Schema learning in attentive tracking of synthetic voices (paradigm 2). (A) Schematic of the trial structure (Upper) and spectrogram of an example stimulus (Lower). A target voice (green curve) was presented concurrently with a distractor voice (red curve). Both voices varied smoothly but stochastically over time in three feature dimensions: f0, F1, and F2 (the fundamental frequency and first two formants; for clarity the schematic only shows variation in a single dimension). Voices in a mixture were constrained to cross at least once in each dimension. Listeners were cued beforehand with the initial portion of the target voice. Following the mixture, listeners were presented with a probe stimulus that was the ending portion of one of the voices and judged whether this probe came from the target. (B) Schematic of the experiment structure. On every other trial the target voice was generated from a common schema. Voices are depicted in three dimensions. f0, F1, and F2 are plotted in semitones relative to 200, 500, and 1,500 Hz, respectively. (C) Results of experiment 5: effect of schemas on attentive tracking (n = 86). The Inset denotes results with trials binned into 42 trials per condition to maximize power for an interaction test (reported in text). Error bars throughout this figure denote the SEM. (D) Results of experiment 6: a control experiment to ensure listeners could not perform the task with cues and probes alone (n = 146). In the last one-third of trials, the voice mixture was replaced with noise. (E) Schema learning on a finer time scale (n = 402). Data from the first 56 trials of experiments 5 and 6 were combined with new data from experiment 7 and replotted with seven trials per bin. The finer binning reveals similar performance at the experiment’s outset, as expected. n.s., not significant. *P < 0.05.