Abstract

Objective

To assess the cost-effectiveness of an enhanced transtheoretical model of behaviour change in conjunction with physiotherapy compared with standard care (physiotherapy) in patients with chronic lower back pain (CLBP).

Design

Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses alongside a multicentre controlled trial from a healthcare perspective with a 1-year time horizon.

Setting

The trial was conducted in eight centres within the Sharon district in Israel.

Participants

220 participants aged between 25 and 55 years who suffered from CLBP for a minimum of 3 months were recruited.

Interventions

The intervention used a model of behaviour change that sought to increase the adherence and implementation of physical activity in conjunction with physiotherapy. The control arm received standard care in the form of physiotherapy.

Primary and secondary measures

The primary outcome was the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of the intervention arm compared with standard care. The secondary outcome was the incremental cost per Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire point.

Results

The cost per QALY point estimate was 10 645 New Israeli shekels (NIS) (£1737.11). There was an 88% chance the intervention was cost-effective at NIS50 000 per QALY threshold. Excluding training costs, the intervention dominated the control arm, resulting in fewer physiotherapy and physician visits while improving outcomes.

Conclusions

The enhanced transtheoretical model intervention appears to be a very cost-effective intervention leading to improved outcomes for low cost. Given limitations within this study, there is justification for examining the intervention within a larger, long-term randomised controlled trial.

Trial registration number

NCT01631344; Pre-results.

Keywords: lower back pain, economic evaluation, QALYs, cost-utility analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, physiotherapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The enhanced transtheoretical model intervention is a novel intervention that integrates behaviour change theory into physical therapy appointments.

Healthcare and medication data were collected via routine data sources providing detailed information on healthcare and medication use.

Generalisability to the region—recruitment methods reflected actual referral processes with nearly all referrals within the Sharon district being included in the study.

Due to the recruitment method reflecting reality, selection bias cannot be ruled out.

No Israel-specific SF-6D algorithm exists and thus quality-adjusted life years will differ if preferences differ between countries.

Introduction

Lower back pain is the number one cause of daily disability worldwide.1 It remains highly prevalent and difficult to treat.2 Increased physical activity is recommended as the most promising and effective approach to treating patients with chronic lower back pain (CLBP).3 Evidence suggests that physical activity is effective in improving function, preventing further pain and improving return to work outcomes.4 5 However, adherence to advice to start and maintain higher levels of physical activity is problematic,6 7 with many people failing to continue to exercise in the long term.7 Criticisms of existing intervention suggest the need for theory-driven interventions that focus on the key obstacles to long-term rehabilitation.7 An enhanced transtheoretical model intervention (ETMI) of behaviour change was developed to address this.8 ETMI seeks to increase the adherence and implementation of physical activity by harnessing theory-informed counselling based on behaviour change principles to overcome barriers to exercise. In line with theory, ETMI matches patients’ readiness to change with an appropriate consultation style from the practitioner. Additionally, it aims to tackle fear of movement, while enhancing reassurance and education about CLBP.

In the primary clinical paper,8 ETMI was found, in an Israeli study, to be more effective than usual physiotherapy as assessed with the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)9 as a primary outcome (2.7 point difference in mean change from baseline). In addition, it performed better on the physical scale of the SF-12 questionnaire,10 worst and average levels of pain, and self-report of levels of physical activity. As well as demonstrating effectiveness, it is important to consider the cost-effectiveness of implementing new interventions. In Israel, interventions that have a cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) less than 50 000 New Israeli shekels (NIS) tend to be approved by the Public Committee and can therefore be considered cost-effective.11 In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) uses the threshold of £20 000–£30 000 per QALY12 to assess cost-effectiveness. This research takes place within the Israeli context. In this paper we seek to answer the question of whether ETMI is more cost-effective than usual care for young patients with CLBP.

Methods

The economic analysis is characterised as a within-trial cost-utility analysis examining the incremental cost per QALY associated with introducing the intervention. The ETMI study was a multicentred, pragmatic controlled trial of patients with CLBP. It is described in detail elsewhere.8 The trial ran between February 2011 and July 2012. Informed consent was mandatory for inclusion within the trial. The trial was registered pre—results on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01631344). This analysis uses a 1-year time horizon (reflecting the clinical paper); hence, costs and outcomes were not discounted. Prices are presented in 2012 terms (the year the trial concluded). Costs are presented in NIS, with Great Britain pounds (GBP) in parentheses. The exchange rate from mid-2012 is used to convert NIS to GBP (NIS6.128=£1).

Population

The trial focused on people aged between 25 and 55 years with CLBP (as defined by a duration of over 3 months) who were referred to the Maccabi Health Services physical therapy clinics within the Sharon district. Older patients were not considered as there is evidence that a transtheoretical approach to increase compliance in older populations is not effective.13 All participants were required to speak Hebrew fluently. Patients with the following contraindications were excluded: rheumatic diseases, tumours, fractures, fibromyalgia, previous spinal surgery, pregnancy and post-car (or work) accident pain.

Recruitment and arm allocation

Eight participating centres were recruited. Across the eight centres, 11 physiotherapists administered the intervention, while 23 provided normal care. All physios had in excess of 4 years of experience. All referrals for physiotherapy from general practice or orthopaedic secondary care within the district were allocated by an independent party to the nearest physiotherapist according to geographical location without knowledge of whether the physiotherapist was within the trial. Although not randomised, the allocation of participants was not under the influence of the study team. On arriving for treatment, eligibility was assessed and eligible participants were provided with information about the trial. Those who did not consent were not included in the study and proceeded to receive treatment as usual.

Interventions

The two arms of the trial can be characterised as follows:

Usual care (control)—The usual care group received standard physical therapy treatment, and this could include mobilisation, manipulation, back exercises, postural training, attending back school, electrical stimulation, short wave diathermy, cooling and stretching.

With the exception of back exercise, the intervention did not use any of the methods associated within the usual care arm. The main aim of the intervention was to facilitate participation in a chosen recreational physical activity through matching and supporting the patient’s cognitive readiness to change, and so reducing known barriers to physical activity such as low motivation, low self-efficacy and fear of movement. A semistandardised protocol was used for the intervention (see online supplementary materials); a full exposition of the enhanced intervention can be found in Ben-Ami et al.8

bmjopen-2017-019928supp001.pdf (165.9KB, pdf)

Resource use and costs

The costing perspective adopted for this study was a healthcare perspective; wider societal costs were not considered. The healthcare perspective included the cost of training staff to deliver the intervention, the cost of delivering the intervention (including the time and materials used) and healthcare costs. Information on healthcare use was captured primarily through the computerised medical records that are available through the Maccabi Healthcare Services. These records were used to extract information on physiotherapist appointments, general practitioner appointments and all pain and inflammation medication; this includes over-the-counter purchases. No data on hospitalisation were captured. Training costs were recorded by the trial team. Unit costs were obtained from the Ministry of Health.14 15 Resource use was retrospectively collected for the 3 months prior to the start of the trial to assess baseline resource use, and for the 12 months of follow-up. Consequently, information was available for all physiotherapy appointments, all doctor appointments, all pain and inflammation medication, and the costs associated with setting up and delivering the intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the economic evaluation was incremental cost per QALYs as recommended.16 QALYs are a unit of outcome that combines both quantity and quality of life into a single metric. QALYs have been widely adopted in many countries around the world (eg, NICE in the UK12). To obtain utility values for QALY calculation within this study, the 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) was included at baseline and both follow-ups (3 months and 12 months). The SF-12 is a generic health-related quality of life questionnaire examining 12 domains of health.10 Algorithms exist to convert SF-12 scores into Short Form Six Dimension (SF-6D) utility values.17–19 As version 1 (US) SF-12 instrument was used, the appropriate algorithm provided by the University of Sheffield was used to calculate utility values.17–19 From baseline through the follow-ups, these health utilities were combined with length of time information to calculate QALYs. QALYs were calculated using the trapezium rule, which calculates the area under the curve.20 The second outcome considered was the RMDQ, a common and well-validated back pain-specific measure9 21 22 suitable to this setting which formed the primary outcome in the clinical evaluation of the intervention.8 The RMDQ is designed to assess disability caused by lower back pain and contains 24 statements relating to disability caused by back pain (eg, I can only walk short distances because of my back). Each answer is worth 1 point, resulting in scores between 0 (no disability) and 24 (severely disabled).

Statistical analysis

First, costs and outcomes between the two arms were compared in isolation. They were then combined within a cost-effectiveness analysis that analysed both costs and outcomes simultaneously. Given the hierarchical structure of the data, appropriate statistical methods were required.23 The primary analysis is a complete case analysis.

Analysis of costs and QALYs

We included relevant characteristics and baseline scores as covariates within a regression framework to control for baseline differences in characteristic or health states.24–26 Due to the clustered nature of the data, it was necessary to use analytical methods that accounted for clustering.23 Multilevel models were adopted allowing for random effects at the physiotherapist and centre level. Finally, the skewness of the data can affect the method of analysis used. Given the skewed cost data collected in the trial, it was necessary to adopt a method that could handle non-parametric data. Generalised linear models27 were therefore implemented using a gamma family and identity link function following tests (data visualisations, modified Park test and ‘linktest’) to optimise model fit. Thus, the final model was a multilevel generalised linear model controlling for baseline characteristics (including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), health state and years of education). This simultaneously addressed the three specified issues relevant to the data. This was implemented within Stata V.1428 using the ‘meglm’ code.

Examining cost-effectiveness

An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) can be calculated by dividing the incremental costs by incremental QALYs. A cost per QALY approach, however, does not reflect that costs and outcomes may be correlated and does not characterise the uncertainty that is present.26 29 To address this, we used the net benefit approach, which combines costs and QALYs into a single metric of net benefit.30 The net benefit approach multiplies QALYs with the willingness to pay (WTP) for those QALYs by the decision maker, and then subtracts the costs.30 This was done for a range of WTP values. To control for clustering, a hierarchical approach was necessary.31 A multilevel regression framework was therefore used for each WTP level to assess the cost-effectiveness while also controlling for baseline imbalances and clustering. Given the parametric nature of net benefits, a generalised linear model was not required; hence, the ‘mixed’ Stata command was used. Within the model, for any WTP, if the intervention coefficient (the incremental net benefit) was greater than 0, then the intervention was deemed cost-effective at that WTP. Using data from the output of the net benefit regressions, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were generated to characterise the uncertainty in decision making at each level of WTP.25 30

Secondary analysis

Cost per RMDQ point was examined as a secondary analysis. The analysis methods outlined above were followed; however, the outcome of interest was ‘difference in RMDQ’ score rather than QALYs.

Sensitivity analyses

We ran two further sensitivity analyses:

Multiple imputation in Stata for missing data: A fixed-effect approach for multiple imputation was used to address the potential impact of missing data. Each arm was imputed separately and 10 imputed data sets were created. We combined data for analysis using Rubin’s rules.32 The same multilevel models previously outlined were then used to analyse the multiply imputed data and to examine cost-effectiveness. A CEAC was generated from the imputed data.

Real-world running costs: Clinician training is a one-off cost, and once up and running there would be no further costs related to training. Thus the same clinicians could conduct the intervention on further cohorts of participants without further training. This sensitivity analysis therefore excluded training costs and only considered the running costs of the intervention.

Results

Baseline characteristics for the two arms of the trial are presented in table 1. Data were collected for 220 participants, of which 109 were in the intervention arm. Arms were well balanced in terms of age, BMI and education. Although not statistically significant, there were notable differences in gender and baseline health utility (0.62 vs 0.66). This is reflected in the baseline resource use and baseline cost data, with the control arm using more healthcare at baseline than the intervention arm. Thus, it was necessary to control for baseline variables within the economic analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline data

| Control arm | Intervention arm | |||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 111 | 42.31 | 7.15 | 109 | 42.37 | 7.55 |

| BMI | 110 | 26.11 | 5.02 | 108 | 26.13 | 4.84 |

| Years of education | 110 | 14.93 | 2.68 | 108 | 14.45 | 2.68 |

| Gender: male | 47 | NA | NA | 54 | NA | NA |

| Gender: female | 64 | NA | NA | 55 | NA | NA |

| Baseline health outcomes | ||||||

| Baseline SF-6D | 107 | 0.62 | 0.13 | 108 | 0.66 | 0.14 |

| RMDQ score | 111 | 10.24 | 5.18 | 109 | 9.95 | 4.95 |

| Baseline resource use | ||||||

| Baseline number of medications | 111 | 1.43 | 1.44 | 107 | 1.37 | 1.50 |

| Baseline number of doctor visits | 111 | 1.58 | 1.30 | 107 | 1.55 | 1.29 |

| Baseline costs | ||||||

| Baseline medication costs (NIS) | 111 | 49.83 | 51.45 | 106 | 45.41 | 53.25 |

| Baseline doctor appointment costs (NIS) | 111 | 197.07 | 162.15 | 107 | 193.93 | 161.28 |

BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable; NIS, New Israeli shekel; RMDQ, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire.

Both arms saw improvements in both utility and RMDQ over time. The mean utility scores in the control arm increased from 0.62 to 0.74, while the control arm saw improvements from 0.66 to 0.79. This suggests that both interventions were beneficial to the patients. For the RMDQ, the control arm improved from 10.24 down to 5.97, while the intervention arm saw improvement from 9.95 to 3.27 (table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome data

| Control | Intervention | |||||

| Baseline | 3 months | 12 months | Baseline | 3 months | 12 months | |

| SF-6D utility by arm | ||||||

| Observations | 107 | 98 | 95 | 108 | 100 | 94 |

| Mean utility | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| SD | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Min | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.42 |

| Max | 0.94 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RMDQ score by arm | ||||||

| Observations | 111 | 98 | 95 | 109 | 100 | 94 |

| Mean RMDQ score | 10.24 | 6.83 | 5.97 | 9.95 | 4.73 | 3.27 |

| SD | 5.18 | 5.91 | 5.51 | 4.95 | 4.66 | 4.45 |

| Min | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 21 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 22 |

RMDQ, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire.

Intervention and healthcare resource use and costs are shown in table 3. The biggest drivers of cost related to the intervention itself were training costs to ensure the intervention was implemented correctly. In terms of intervention materials, the intervention is very cheap, owing to the fact that the only extra materials are instructional postcards for intervention participants. The primary cost of the intervention is the physiotherapy care itself; due to the nature of the intervention, it is impossible to disentangle where the ETMI care ends and other physiotherapy appointments begin, thus intervention costs related to ETMI are captured within the healthcare costs. There were lower levels of resource in terms of medication, doctor visits and physiotherapist appointments for the intervention arm compared with the control arm. The most notable difference relates to physiotherapy appointments used: the control arm had on average 5.11 appointments at a cost of NIS643.62 (£105.03) per patient compared with just 3.62 at a cost of NIS455.72 (£74.36) per patient for the intervention arm. The baseline and centre-adjusted cost difference specifically for physiotherapy appointments demonstrated a saving of NIS191.79 (95% CI 289.51 to 94.07), and this is statistically significant (P=0.00).

Table 3.

Resource use and costs

| Intervention costs (cluster level) | ||||||

| Component | Details | Resource used | Unit cost (NIS) | Total cost (NIS) | Cost per intervention physiotherapist (NIS) | Cost per intervention patient (NIS) |

| Physiotherapist training | 12 trainees attended: 2 days | 192 hours | 126 per 30 min | 48 384 | 4398.55 | 443.89 |

| Trainers’ time: 2 days | 16 hours | 126 per 30 min | 2016 | 183.27 | 18.50 | |

| Materials | Postcards for physiotherapists | 13 per physio | 650 total | 650 | 59.09 | 5.96 |

| Total: | 51 050 | 4640.91 | 468.35 | |||

| Healthcare resource use and cost data (unadjusted) | ||||||||||

| Control arm (missing n=0) | Intervention arm (missing n=2) | |||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | Min | Max | n | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| Medication used | 111 | 1.60 | 2.68 | 0 | 22 | 107 | 1.21 | 2.11 | 0 | 17 |

| Doctor visits | 111 | 1.49 | 2.47 | 0 | 12 | 107 | 1.02 | 1.97 | 0 | 17 |

| Physio appointments | 111 | 5.11 | 3.44 | 1 | 18 | 107 | 3.62 | 1.97 | 1 | 12 |

| Medication costs (NIS) | 111 | 48.38 | 80.97 | 0 | 595.88 | 107 | 39.49 | 76.50 | 0 | 654.02 |

| Doctor costs (NIS) | 111 | 185.81 | 308.90 | 0 | 1500 | 107 | 127.34 | 245.83 | 0 | 2125 |

| Physio costs (NIS) | 111 | 643.62 | 432.94 | 126 | 2268 | 107 | 455.72 | 248.19 | 126 | 1512 |

NIS, New Israeli shekel.

The intervention arm was associated with an extra 0.02 QALYs (95% CI −0.01 to 0.05) per intervention participant compared with the control arm. Reflecting the QALY results, the condition-specific RMDQ demonstrated a reduction in RMDQ score of 2.67 (95% CI −4.03 to –1.31) in comparison with the control arm. Incremental costs were higher for the intervention arm, with a cost difference of NIS230.35 (£37.59) per participant (95% CI NIS85.26 to NIS375.44). Thus, costs were higher for the intervention arm, but outcomes were better (table 4).

Table 4.

Incremental analysis: intervention versus control—fully adjusted for baseline, covariates and clustering

| Mean difference | SE | z | P>z | 95% CI | 95% CI | |

| QALYs | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.45 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Change from baseline RMDQ | −2.67 | 0.69 | −3.85 | 0.00 | −4.03 | −1.31 |

| Cost (NIS) | NIS230.35 | 74.03 | 3.11 | 0.002 | 85.26 | 375.44 |

| Cost per QALY | NIS10 645.12 | |||||

| Cost per RMDQ point | NIS86.27 | |||||

NIS, New Israeli shekel; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RMDQ, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire.

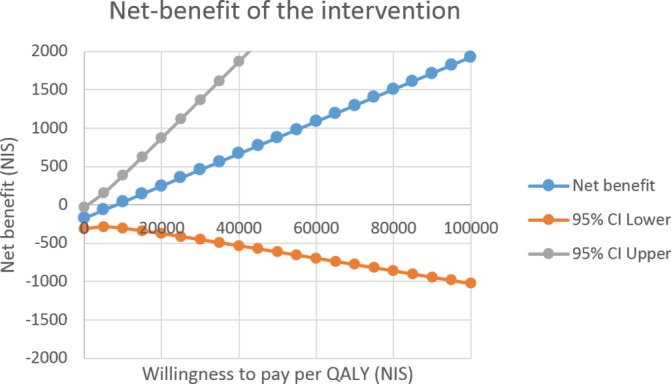

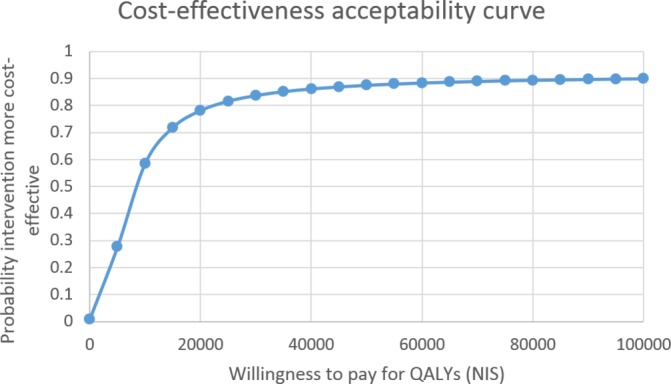

The net benefit (NB) curve intersects the x-axis at approximately NIS10 000 (£1631.85) (figure 1). This point reflects where NB is equal to 0 and thus approximates the cost per QALY. The lower CI never crosses 0. This suggests that regardless of WTP, there will always be some uncertainty surrounding the result. This reflects the modest intervention effects and the increased costs related to the intervention. The CEAC in figure 2 shows the probability at different levels of WTP that the intervention is more cost-effective than the control. At very low levels of WTP, the control arm is likely the more cost-effective option, with the intervention just having a 27% chance of being the more cost-effective option at a WTP of NIS5000 (£815.93). As WTP for QALYs rises, the probability of the intervention quickly increases. At a WTP of NIS20 000 (£3263.71) per QALY, there is a 78% chance that the intervention is the more cost-effective option. This rises to 88% by a WTP of NIS50 000 (£8159.27), before stabilising at about 89% for higher WTP levels.

Figure 1.

Net benefit by willingness to pay (New Israeli shekel, NIS) for quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: probability intervention is cost-effective at different levels of willingness to pay (New Israeli shekel, NIS) for quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).

Secondary analysis

The adjusted mean change in RMDQ score between the two arms was −2.67 (P=0.000). The CEAC analysis associated with the RMDQ scores found that even at a very low WTP of NIS100 (£16.32) per RMDQ point, there is a 81% chance the intervention is the more cost-effective option. By NIS200 (£32.64), there is a 99% chance the intervention is the more cost-effective option.

Sensitivity analyses

The first sensitivity analysis addresses the issue of missing data. Attrition was relatively low with just 14% of SF-6D scores being missing at the final follow-up. Multiple imputation of missing data has limited impacts on the results. At a WTP of NIS50 000 (£8159.27) per QALY, there is an 85% chance that the intervention is the more cost-effective, only 3% less than the complete case analysis.

The second sensitivity analysis considers the real-world running costs: excluding all costs related to training. In this scenario the intervention is actually cost-saving, saving NIS−252.61 (95% CI −381.92 to 123.30) (£41.86) per patient. In this sensitivity analysis the intervention dominates the control arm: it is associated with lower costs and better outcomes.

Discussion

This paper has reported the first cost-effectiveness analysis of an ETMI aiming to increase recreational physical activity in patients with chronic low back pain compared with physiotherapy usual care. Echoing the main study findings,8 both trial arms improved; however, the intervention arm was associated with better outcomes compared with the usual care arms as measured by the RMDQ and QALYs. This suggests ETMI may be useful in reducing CLBP, but at what cost? In the 12 months following the intervention, doctor and physiotherapy appointments, as well as medication use, were all comparatively reduced in the intervention arm. Training costs however outweighed these cost savings. This biggest cost driver was training costs for delivery of the intervention. The point estimate of the ICER was NIS10 645 (£1737.11) per QALY. No explicit cost per QALY threshold exists in Israel; it however has been reported that interventions with a cost per QALY less than NIS50 000 (£8159.27) tend to be approved by the Public Committee.11 Thus, with a cost per QALY of NIS10 645 (£1737.11), the ETMI represents good value for money and has a very high probability (88%) of being cost-effective at the implied threshold. Overall our results were robust to sensitivity analyses, with multiple imputation for missing data having little impact on key results.

Our primary analysis is very conservative as it assumes all of the training costs are allocated to the limited number of people treated within the trial. If implemented in practice each trained physiotherapist will treat many more people than just those included in the study. Indeed, it could be argued that it is inappropriate to include any training costs in the model as these will be met elsewhere as part of the normal overall running costs of the service. When considering only the ongoing costs, the ETMI dominated usual care; that is, it was cheaper and more effective. Regardless of how the training costs are managed in the analyses, these data indicate that ETMI is very likely to be cost-effective when compared with usual care and it might even be cost-saving. This reflects the findings of a recent review that suggest interventions that combine physical and psychological treatments are more likely to be cost-effective for CLBP.33

There are a number of strengths and limitations associated with the methodology of the study and this analysis. The study is novel in integrating transtheoretical models of behaviour change into routine physiotherapy appointments. A key strength and limitation of the study relates to the method of recruitment into the study. The recruitment method reflected the real-world referral process and nearly all referrals within one geographical district were included. A limitation to this method of recruitment was that participants were allocated to their nearest geographically available physical therapist (the referrer had no knowledge of the physiotherapist’s allocation), and thus it cannot claim to be a ‘randomised’ controlled trial; we cannot rule out selection bias. This however should be limited by the fact that each treatment centre contained at least one physio in the intervention arm, and one in the control arm, and those allocating patients to physiotherapists were not aware of which arm each physio was in. Likewise, the sample size is relatively small and is potentially underpowered, increasing the uncertainty around results. The use of routine data to collect information on resource use was a strength allowing the collection of detailed data on medication, doctor visits and physiotherapist visits; however, a limitation to this approach was that no information on hospital use was collected and key costs potentially could have been missed. Given the intervention arm reported less disability and higher utility scores, it is unlikely the inclusion of such costs would have changed the direction of the results. The Israeli Ministry of Health does not specify a preferred utility measure to generate QALYs.16 In this study the SF-12 was used to capture generic health-related quality of life data and QALYs were derived using the associated utility algorithm.17 A limitation of this is that the study was conducted in Israel and no Israel-specific tariff exists, and preferences for health states may differ from those where the tariff originates. Furthermore, although the SF-12 is validated and reliable for patients with lower back pain,34 the evidence surrounding the SF-6D is more limited35 and future studies should explore the use of other utility measures. CLBP by definition is a chronic condition; the 1-year follow-up is therefore a limitation as the long-term effectiveness and adherence could not be thoroughly assessed. Given one of the prime issues with CLBP is absence from work, and a key goal of treatment for CLBP is to enable return to work, it is a limitation that no data were collected on whether return to work was achieved. Given the comparative improvement within the intervention arm, it is not unreasonable to presume that ability to work would also improve in this arm. This implies that wider productivity gains may have been accrued by the intervention arm that we have failed to capture. The study focused on younger populations, below age 55, and we cannot generalise the effect to older groups. While the study took place in a single district, it included a wide variety of socioeconomic groups and represents a large section of the Israeli population, which has only six districts in total.

Future research should focus on addressing the limitations within this economic evaluation by conducting a larger scale randomised controlled trial. To comprehensively address limitations, a future trial would incorporate the following: larger sample size; using a randomisation procedure to allocate patients to trial arms; including multiple measures of utility specific to the setting; examining the mechanism of change and long-term adherence; and collecting resource use information on hospitalisation and wider impacts (eg, employment).

Conclusions

The use of ETMI was associated with fewer medical appointments and fewer medications being necessary. At the same time, outcomes were improved for patients who received the intervention. In summary, the findings within this study are very encouraging and suggest that ETMI is a cost-effective strategy for treating CLBP, at least in younger populations, with an 88% probability of being more cost-effective than usual care. However there are a range of limitations to this study, combined with a modest sample size (n=220), and as such this should be considered a pilot study for a large-scale, long-term randomised controlled trial to robustly test the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ETMI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AC conducted the economic analysis and drafted the paper. NB-A was responsible for setting up the trial and conducting the data collection under the supervision and guidance of TP, YS and GC. MU, TP and NB-A contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by Maccabi Healthcare Services (an Israeli public health organisation).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committees of both Tel-Aviv University and Maccabi Healthcare Services (a public health organisation).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data requests relating to the ETMI trial should be made to noaba@ariel.ac.il.

References

- 1. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. . The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, et al. . Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2014;17:3–10. 10.1111/ner.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernstein IA, Malik Q, Carville S, et al. . Low back pain and sciatica: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2017;356:i6748 10.1136/bmj.i6748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, et al. . Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:193–204. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weiner SS, Nordin M. Prevention and management of chronic back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:267–79. 10.1016/j.berh.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beinart NA, Goodchild CE, Weinman JA, et al. . Individual and intervention-related factors associated with adherence to home exercise in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2013;13:1940–50. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pincus T, McCracken LM. Psychological factors and treatment opportunities in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013;27:625–35. 10.1016/j.berh.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ben-Ami N, Chodick G, Mirovsky Y, et al. . Increasing Recreational Physical Activity in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:57–66. 10.2519/jospt.2017.7057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 1983;8:141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shmueli A. Economic evaluation of the decisions of the Israeli Public Committee for updating the National List of Health Services in 2006/2007. Value Health 2009;12:202–6. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NICE. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013: NICE, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Basler HD, Bertalanffy H, Quint S, et al. . TTM-based counselling in physiotherapy does not contribute to an increase of adherence to activity recommendations in older adults with chronic low back pain--a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2007;11:31–7. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ministry of Health Israel. Ministry of health price list for ambulatory and hospitalization services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. YARPA. Local System Israeli Drug Catalogue: YARPA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ministry of Health Israel. Guidelines for the submission of a request to include a pharmaceutical product in the national list of health services: Ministry of Health Pharmaceutical Administration, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 2004;42:851–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kharroubi SA, Brazier JE, Roberts J, et al. . Modelling SF-6D health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. J Health Econ 2007;26:597–612. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCabe C, Brazier J, Gilks P, et al. . Using rank data to estimate health state utility models. J Health Econ 2006;25:418–31. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ 2005;14:487–96. 10.1002/hec.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deyo RA, Andersson G, Bombardier C, et al. . Outcome measures for studying patients with low back pain. Spine 1994;19:2032S–6. 10.1097/00007632-199409151-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacob T, Baras M, Zeev A, et al. . Low back pain: reliability of a set of pain measurement tools. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82:735–42. 10.1053/apmr.2001.22623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gomes M, Grieve R, Nixon R, et al. . Methods for covariate adjustment in cost-effectiveness analysis that use cluster randomised trials. Health Econ 2012;21:1101–18. 10.1002/hec.2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoch JS, Briggs AH, Willan AR. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue: a framework for the marriage of health econometrics and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ 2002;11:415–30. 10.1002/hec.678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoch JS, Rockx MA, Krahn AD. Using the net benefit regression framework to construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of external loop recorders versus Holter monitoring for ambulatory monitoring of “community acquired” syncope. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:68 10.1186/1472-6963-6-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoch JS, Dewa CS. Advantages of the Net Benefit Regression Framework for Economic Evaluations of Interventions in the Workplace. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:441–5. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barber J, Thompson S. Multiple regression of cost data: use of generalised linear models. J Health Serv Res Policy 2004;9:197–204. 10.1258/1355819042250249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gomes M, Ng ES, Grieve R, et al. . Developing appropriate methods for cost-effectiveness analysis of cluster randomized trials. Med Decis Making 2012;32:350–61. 10.1177/0272989X11418372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fenwick E, Marshall DA, Levy AR, et al. . Using and interpreting cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of management strategies for atrial fibrillation. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:52 10.1186/1472-6963-6-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bachmann MO, Fairall L, Clark A, et al. . Methods for analyzing cost effectiveness data from cluster randomized trials. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2007;5:12 10.1186/1478-7547-5-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andronis L, Kinghorn P, Qiao S, et al. . Cost-Effectiveness of Non-Invasive and Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Low Back Pain: a Systematic Literature Review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2017;15:173–201. 10.1007/s40258-016-0268-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luo X, George ML, Kakouras I, et al. . Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the short form 12-item survey (SF-12) in patients with back pain. Spine 2003;28:28 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083169.58671.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Finch AP, Dritsaki M, Jommi C. Generic preference-based measures for low back pain. Spine 2016;41:E364–74. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019928supp001.pdf (165.9KB, pdf)