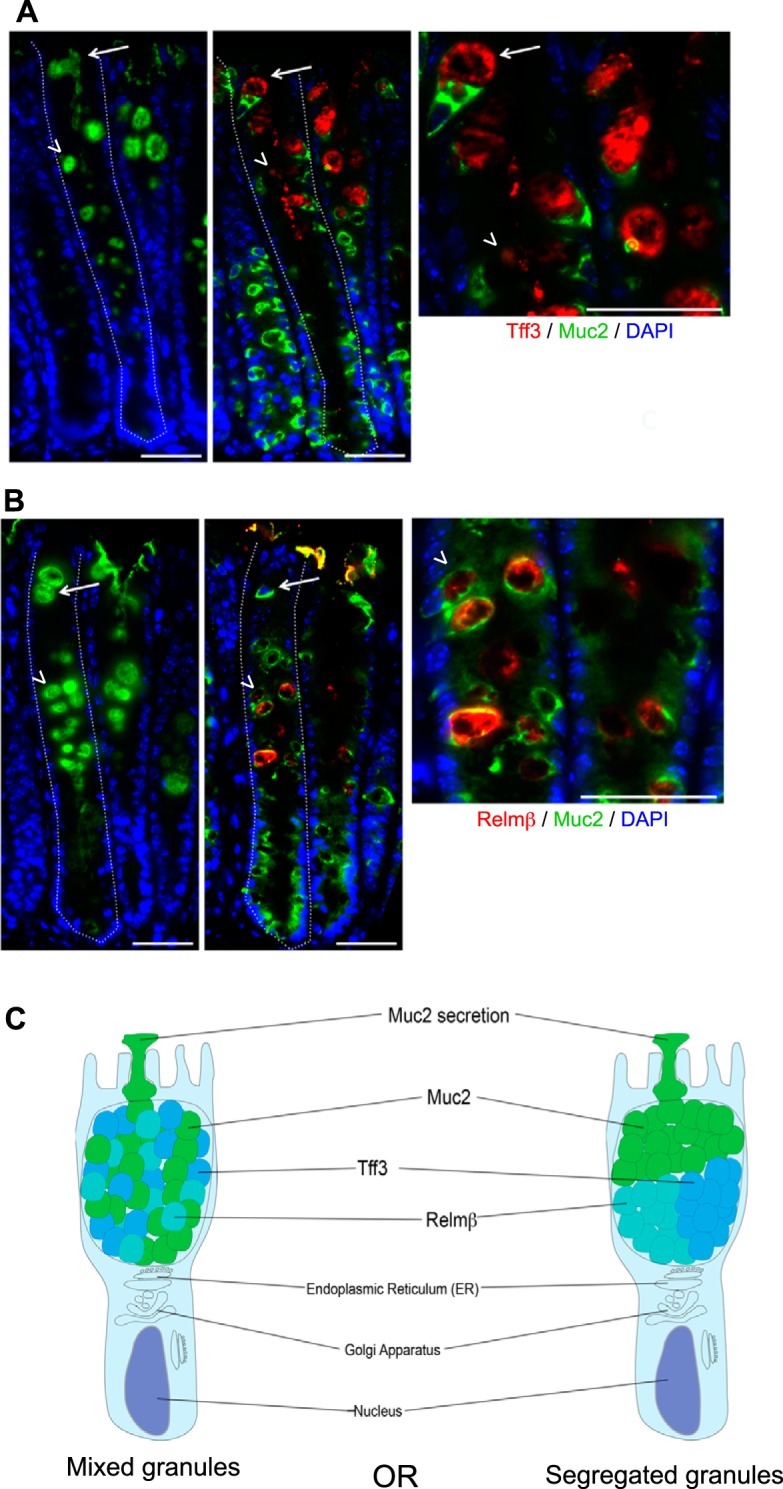

Fig. 3.

Expression of Tff3 and Relm-β in colonic goblet cells (GCs) during Citrobacter rodentium infection. Immunofluorescent staining of colonic tissue from a C57BL/6 mouse, 6 days post-C. rodentium infection. A, left: presence of GCs stained by using Santa Cruz anti-Muc2 (H300) antibody (green), targeting the mature form of Muc2. Middle: the same GCs on a serial cut section expressing both the Tff3 (red) and precursor (immature) form of Muc2, stained by using a Santa Cruz anti-Muc2 (P18) antibody (green; white arrows). Host cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Right: the higher magnification inset confirms that GCs express both Tff3 and Muc2 (white arrow). Colonic crypts (dashed white lines), GCs expressing Tff3 (white arrows), and GCs expressing Relm-β from B (arrowheads). Original scale bars, 50 μm. B, left: presence of GCs stained by using Santa Cruz anti-Muc2 (H300) antibody (green), targeting the mature form of Muc2. Middle: the same GCs on a serial cut section expressing both Relm-β (red) and the precursor form of Muc2, stained by using a Santa Cruz anti-Muc2 (P18) antibody (green; white arrowheads). Host cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Right: the higher magnification inset confirms that GCs express both Relm-β and Muc2 (white arrowhead). Colonic crypts (dashed white lines), GCs expressing Tff3 from A (white arrows), and GCs expressing Relm-β (arrowheads). Original scale bars, 50 μm. C: a cartoon outlining the possibility that intestinal GCs produce secretory granules containing Muc2, Relm-β, and Tff3 that are intermixed throughout the theca or an alternative possibility: that the different granules are segregated within the body of the theca.