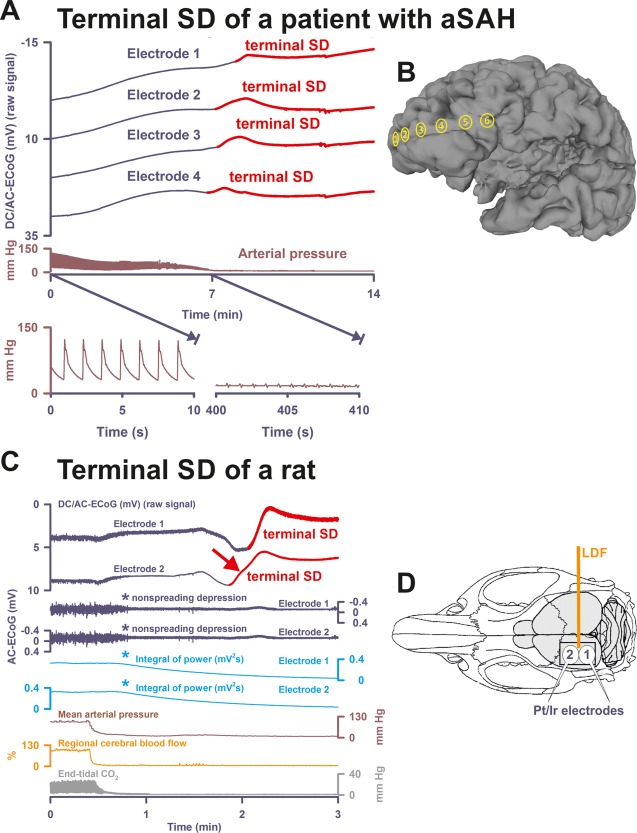

Figure 1.

Terminal spreading depolarization (SD) during death in the human brain in comparison to terminal SD during death in the rat brain. (A) In Patient 1, the first direct current (DC) change after terminal extubation was a very slow, homogeneous DC positivity (not shown; cf Table 1) that began before the circulatory arrest. Terminal SD then started at electrode 4 (transition from dark blue to red DC traces) after the arterial pressure had reached its minimum (brown trace). Systemic arterial pressure was recorded in the radial artery. The 2 insets show the arterial pressure fluctuations during the initial period and during the arrest of the systemic circulation. Note that there is still evidence of cardiac cycles in the right inset, but the cardiac output is too low to maintain a sufficient systemic pressure (electromechanical dissociation). This increasingly pulseless electrical activity of the heart disappeared 30 seconds thereafter. Spontaneous brain activity had ceased in response to the barbiturate thiopental several hours before the circulatory arrest. Therefore, no nonspreading depression of activity occurred (not shown). (B) Projection of the electrodes of a typical subdural, collinear recording strip on a human brain. (C) Dying process after circulatory arrest in a rat. (D) Original cranial window experiment using 2 subdural Pt/Ir plate electrodes for use in humans (DC/AC‐ECoG) and a laser‐Doppler flowmetry (LDF) probe (regional cerebral blood flow [rCBF]). Note the steep falls in arterial pressure and rCBF that mark the moment of circulatory arrest. In animals, the typical sequence of nonspreading depression followed by terminal SD during global cerebral anoxia–ischemia has been extensively documented since its first description in 1947.7, 11, 12, 13, 14 Note the similarity between the patterns of the terminal SD in the rodent experiment and in the patient (red arrows in A and C). In both cases, the terminal SD propagated from one electrode to the next corresponding with previous evidence from experiments in animals in vivo and in brain slices.7, 12, 13, 14 In contrast to the spread of the terminal SD, the nonspreading depression (cf asterisks) is seen in the rodent recordings as a silencing of the spontaneous electrical activity (alternating current [AC]–electrocorticography [ECoG]: 0.5–45Hz) that develops simultaneously across the array of the regional 2 electrodes (cf Figs 3B, 4B, 5A, 5C, and 6 for nonspreading depression in patients). In the clinic, it has become conventional to review the raw signal alongside a leaky integral of the total power of the bandpass‐filtered (AC‐ECoG) data and measure depression duration based on the latter.16, 23 Therefore, the integral of power is shown here to display the pattern of nonspreading depression when this type of data presentation is chosen (light blue traces, cf Patient 3 in Fig 4A and Patient 7 in Fig 6). The experiment was performed in a male Wistar rat (300g, 12 weeks old, supplied by Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) anesthetized with 100mg/kg body weight thiopental–sodium intraperitoneally (Trapanal; BYK Pharmaceuticals, Konstanz, Germany), tracheotomized, and artificially ventilated (Effenberger Rodent Respirator; Effenberger Med.‐Techn. Gerätebau, Pfaffing/Attel, Germany; approved by the Office for Occupational Safety and Health and Technical Security Berlin [G0152/11]). Sudden circulatory arrest was induced in the rat by injection of 10ml of air into the heart via the femoral vein. This explains why mean arterial pressure rapidly dropped in the rat in contrast to the patient, in whom the circulatory arrest developed gradually after extubation. The Supplementary Table provides the statistical description of 5 rats with a previously healthy brain in which death resulted from sudden circulatory arrest after air injection into the femoral vein and heart under thiopental anesthesia. aSAH = aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.