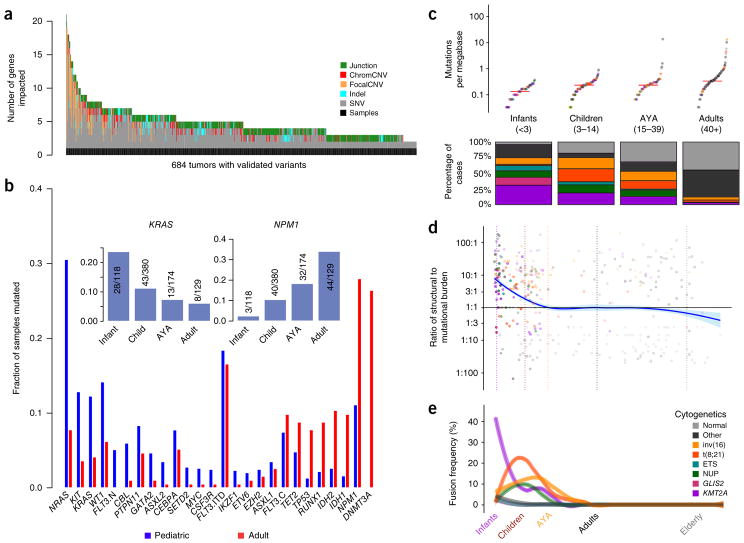

Figure 2.

Age-related differences in mutational and structural alterations in AML. (a) Distribution of variants per sample. At least one variant impacting a gene recurrently altered in pediatric AML was identified using multiplatform-validated variants in 684 subjects. Junction, protein fusion (Online Methods); chromCNV, chromosome-arm- or band-level copy variant; focalCNV, gene-level copy variant. (b) Age-dependent differences in the prevalence of mutations. FLT3 mutations are plotted in three categories: ITD (FLT3.ITD), activation loop domain (FLT3.C) and new, childhood-specific changes (FLT3.N). The inset shows a pattern of waxing or waning mutation rates across age groups that is evident in selected genes (KRAS and NPM1 are illustrated). (c) Top, childhood AML, like adult AML, has a low somatic mutation burden (Supplementary Fig. 5). Bottom, childhood AML is more frequently impacted by common cytogenetic alterations than adult AML. For the color key for c–e, see the legend in e. Midlines represent medians. (d) The ratio of the structural variation burden to that of SNVs and indels is high in infancy and early childhood and declines with age. Vertical dashed lines demarcate age groups, and plot points are represented in the same colors as in e. (e) Using a sliding-window approach to account for uneven sampling by age, the incidence of common translocations in AML is shown to follow age-specific patterns (multivariate chi-squared P < 10−30) and was greatest in infants as compared to all other ages (chi-squared P < 10−22). KMT2A fusions were most common in infants (chi-squared P < 10−20), and CBF fusions tended to affect older children (chi-squared P < 10−7). ETS and NUP refer to mutations in these gene families. GLIS2 and KMT2A refer to fusions involving these genes.