Abstract

Objective

To examine the strength and direction of the association between urinary symptoms and both poor quality sleep and daytime sleepiness among women with urgency urinary incontinence

Methods

A planned secondary analysis of baseline characteristics of participants in a multicenter, double-blinded, 12-week randomized controlled trial of pharmacologic therapy for urgency-predominant urinary incontinence in ambulatory women self-diagnosed by the 3 Incontinence Questions (3IQ). Urinary symptoms were assessed by 3-day voiding diaries. Quality of sleep was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and daytime sleepiness using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).

Results

Of the 640 participants, mean (SD) age was 56 (±14) years, 68% were white. Participants reported an average of 3.9 (±3.0) urgency incontinence episodes per day and 1.3 (±1.3) episodes of nocturia per night. At baseline, 57% had poor sleep quality (PSQI score > 5) and 17% reported daytime sleepiness (ESS score >10). Most women (69%) did not use sleeping medication during the prior month while 13% reported use of sleeping medication three or more times per week. An increase in total daily incontinence episodes, total daily urgency incontinence episodes, total daily micturitions, and moderate to severe urge sensations were all associated with higher self-report of poor sleep quality according to the PSQI (all p≤0.01). Higher scores on the Bother Scale and the Health-Related Quality of Life for overactive bladder on the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire were similarly associated with higher rates of poor sleep quality (both p≤0.01). In subgroup analysis of those who took sleeping medications less than twice a week, there was still a significant relationship between incontinence measures and quality of sleep as measured by the PSQI. In multivariable analyses, greater frequency of nighttime urgency incontinence was associated with poor sleep quality (p=0.03).

Conclusions

Among ambulatory women with urgency urinary incontinence, poor sleep quality is common and greater frequency of incontinence is associated with a greater degree of sleep dysfunction. Women seeking urgency urinary incontinence treatment should be queried about their sleeping habits so that they can be offered appropriate interventions.

Keywords: Urgency urinary incontinence, quality of sleep, daytime sleepiness

INTRODUCTION

Urinary incontinence is common among women in the United States with a prevalence rate of up to 77%.1 Between 26% and 61% of women will seek care for urinary incontinence. 2–4 While urinary incontinence is not associated with an increased mortality,5 it has significant adverse impact on quality of life, sexual function, medical morbidity and caregiver burden.6–8

Nocturia, a symptom frequently reported with urgency urinary incontinence, is a common symptom associated with many sleep disorders9 and in a population based study out of Europe was the most common cause of sleep disturbance.10 Disordered sleep is multifaceted and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders lists seven major categories with more than sixty distinct diagnosis. Because sleep disorders are associated with a wide range of diagnosis, it is difficult to determine an overall prevalence however the Institute of Medicine estimates that 50–70 million Americans chronically suffer from disorders of sleep and wakefulness representing around 20% of the population.11 Other common causes of sleep dysfunction in the United States include moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea which affects around 10% of the population, restless leg syndrome which affects 5% of the population. 11

Despite the known relationship between nocturia and sleep disturbances, the relationship between urinary incontinence, specifically urgency urinary incontinence, and sleep has not been fully characterized. Up to 40% of women with nocturia may have no other lower urinary tract symptoms and therefore conclusions about women with nocturia may not be applicable to those with overactive bladder.12 In particular, it is not clear whether incontinence has a direct impact on sleep independent of nocturia, or whether the severity of sleep disturbance may be proportional to the severity or frequency of incontinence. Ultimately we sought to identify women at highest risk for dysfunctional sleep in order to guide care providers in identifying patients who may need additional screening and interventions. The goals of this study were two-fold; first, determine the prevalence of poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness among women with urgency predominant urinary incontinence and second determine the strength and direction of the associations between urinary symptoms and sleep outcomes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a multicenter, double-blinded, 12-week randomized placebo-controlled trial of oral pharmacological therapy for urgency-predominant incontinence in women self-diagnosed by the simple 3IQ. Study methods for the parent trial have been reported previously.13 In brief, the study population included women aged 18 years and older with self-reported urgency or mixed urgency predominant urinary incontinence, with at least three episodes of urgency urinary incontinence on a 3-day bladder diary. Women were excluded if they self-reported complex medical histories that would require a specialist evaluation for incontinence before initiating pharmacological therapy. While women taking sleeping medication were eligible for enrollment, those receiving treatment for urgency urinary incontinence were excluded. All patients from the parent trial were included in this secondary analysis.

Measures

At the initial visit, participants completed questionnaires on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, race or ethnicity, education), health-related habits (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption), medication use, reproductive (e.g., parity, menopause status), medical history (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, stroke, chronic liver disease), surgical history (e.g., previous hysterectomy) and incontinence (e.g., age of onset of incontinence, and duration (in years) of incontinence).

Sleep outcomes were measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)14 and daytime sleepiness assessed by Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).15 The PSQI is a self-reported questionnaire that assesses sleep quality over a one-month period and consists of 19-items weighted on a 0–3 interval scale. The scales are classified into seven components including sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction. A global score is calculated by totaling the seven component scores providing an overall score ranging from 0 to 21 with lower scores indicative of better sleep quality. The ESS is a self-reported questionnaire that assesses daytime sleepiness and the participant’s probability of falling asleep in eight different situations on a scale from 0–3 with a total score from 0 to 24.15,16

At baseline, women also completed a validated 3-day voiding diary in which they recorded each time they experienced incontinence or voided into the toilet, classified incontinence episodes by type (urgency, mixed, other), and rated the degree of urgency associated with each episode (none, mild, moderate, or severe).17 Participants completed the Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC), a validated single-item global measure of patients’ subjective impression of their current urinary problems.18 Participants also completed the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q), a 33-item, condition-specific measure designed to assess the impact of OAB symptoms. The OAB-q contains a symptom bother subscale (8-item scale) and a Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) subscale (25-item scale). The score for each of OAB-q domain are summed and adjusted such that they range from zero to 100 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms or better quality of life.19

Statistical Analysis

For this planned secondary data analysis, poor sleep quality was defined as PSQI score of >5 (diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% in distinguishing poor compared to good sleepers).14 Daytime sleepiness was defined by an ESS >10 since this has been shown to indicate significant daytime sleepiness.16 Baseline demographics, health history and lower urinary tract symptoms were compared between groups using chi-square or kurskal-wallis. Multivariable analysis was performed controlling for clinical site and smoking status. Relationships between sleep quality and the number of UI episodes and number of voids was examined by plotting the rate of poor sleep quality for each number of events and testing for a linear trend in logistic regression models. Additional multivariable modeling was performed by including each lower urinary tract symptoms (number of daytime urgency urinary incontinence episodes, daytime stress urinary incontinence episodes, nighttime urgency urinary incontinence episodes, stress urinary incontinence and non-urinary incontinence voids and average urgency ratings) in order to determine the independent contribution of each to poor sleep quality. Analyses were also conducted excluding respondents who used sleep medication frequently (≥3 times per week). A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 645 participants enrolled, mean (SD) age was 56 (±14) years, and 68% were white. Women reported an average of 3.9 (±3.0) urgency incontinence episodes per day and 1.3 (±1.3) episodes of nocturia per night. Six-hundred and forty women completed the PSQI questionnaire with 371 (58%) reporting poor sleep quality (PSQI >5); 643 completed the ESS questionnaire with 107 (17%) reporting daytime sleepiness (ESS score >10). The use of sleep medications was not common in our cohort, and 441 (69%) reported no use of sleep medications in the past month, while 13% reported use of sleep medication three or more times per week.

No significant difference in age, race/ethnicity, marital status, menopausal status or parity were detected between participants with and without poor sleep quality as defined by PSQI (Table 1). Participants with poor sleep quality were less likely to report their overall health as excellent or very good (70.6 vs. 90.0%; p<0.01) and more likely to report current cigarette smoking (17.3 vs 10.4%, p=0.04). When controlling for clinical site and smoking status, we found the same significant relationships between lower urinary tract symptoms and sleep quality (Table 3). Participants with poor sleep quality also reported more total incontinence episodes per day (5.03 vs 4.17; p<0.01), more total urgency incontinence episodes per day (4.18 vs 3.48, p<0.01), greater frequency of daytime, nighttime and total micturitions (10.3 vs 9.6 episodes; p=0.01). Urge sensation was more common among those with poor sleep quality (p<0.01). On the OAB-q, Participants with poor sleep quality reported higher scores representing greater impact of their incontinence (40.3 vs 31.4, p<0.01). In subscale analysis of the OAB-q, women with poor quality sleep also reported higher scores on the bother scale and HRQoL scale.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by sleep quality as assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), n=640

| Select demographic characteristics | PSQI* ≤ 5, n=269 | PSQI* > 5, n=371 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 57 (15) | 56 (14) | 0.28 |

| History of hysterectomy, n (%) | 85 (31.6) | 108 (29.1) | 0.50 |

| Not currently menstruating, n (%) | 193 (71) | 263 (71.3) | 0.90 |

| Current diuretic use, n (%) | 46 (17) | 57 (15) | 0.88 |

| Current estrogen use, n (%) | 24 (8.9) | 28 (7.5) | 0.53 |

| Current cigarette smoking, n (%) | 28 (10.4) | 64 (17.3) | 0.016 |

| Current weekly alcohol use, n (%) | 92 (34) | 102 (27) | 0.064 |

| Excellent or very good overall health **, n (%) | 242 (90) | 262 (71) | <0.001 |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms, per day | |||

| Total incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 4.2 (2.7) | 5.0 (3.8) | 0.028 |

| Total urgency incontinence episodes, mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.2) | 4.2 (3.3) | 0.080 |

| Total daytime incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.3) | 4.2 (3.1) | 0.101 |

| Total nighttime incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.8 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Total micturitions, mean (SD) | 9.6 (3.0) | 10.3 (3.5) | 0.031 |

| Total daytime micturitions, mean (SD) | 8.5 (2.6) | 8.9 (3.0) | 0.20 |

| Total nighttime micturitions, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.3) | 0.004 |

| Total severe urgency sensation, mean (SD) | 3.0 (3.1) | 4.0 (3.7) | <0.001 |

PSQI score of greater than 5 has a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% in distinguishing good and poor sleepers

Participants reported their perceptions of their overall health status as poor, satisfactory, good, very good or excellent

Table 3.

Multivariable model of lower urinary tract symptoms stratified by measures of sleep‡

| Lower urinary tract symptoms, per day | PSQI ≤ 5, n=269 | PSQI > 5, n=371 | P value | ESS ≤ 10, n=269 | ESS > 10, n=371 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 4.17 ( 2.7) | 5.03 ( 3.8) | 0.007 | 4.63 ( 3.3) | 4.94 ( 4.0) | 0.50 |

| Total urgency incontinence episodes, mean (SD) | 3.48 ( 2.2) | 4.18 ( 3.3) | 0.005 | 3.86 ( 2.8) | 4.11 ( 3.3) | 0.52 |

| Total daytime incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 3.68 ( 2.3) | 4.26 ( 3.1) | 0.034 | 3.98 ( 2.7) | 3.98 ( 2.7) | 0.39 |

| Total nighttime incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 0.49 ( 0.8) | 0.76 ( 1.1) | 0.002 | 0.65 ( 1.0) | 0.64 ( 1.1) | 0.87 |

| Total micturitions, mean (SD) | 9.59 ( 3.0) | 10.31 ( 3.5) | 0.015 | 10.00 ( 3.3) | 10.15 ( 3.3) | 0.64 |

| Total daytime micturitions, mean (SD) | 8.49 ( 2.6) | 8.90 ( 3.0) | 0.16 | 8.73 ( 2.9) | 8.84 ( 3.0) | 0.62 |

| Total nighttime micturitions, mean (SD) | 1.11 ( 1.1) | 1.41 ( 1.3) | 0.003 | 1.27 ( 1.3) | 1.31 ( 1.3) | 0.93 |

| Total severe urgency sensation, mean (SD) | 3.02 ( 3.1) | 3.02 ( 3.1) | 0.007 | 3.51 ( 3.3) | 3.95 ( 4.1) | 0.25 |

Multivariable analysis adjusted for smoking status and clinical site

Participants with daytime sleepiness (ESS score >10) were less likely to report their overall health to be excellent or very good compared to those with normal daytime sleepiness (69.2% vs 80.6%, p<0.01)(Table 2). There were no significant differences in measures of incontinence, including total incontinence episodes, urgency incontinence episodes, micturitions, urge sensations or OAB-q when stratified by daytime sleepiness.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by daytime sleepiness as assessed by the Epworth Sleep Quality Scale (ESS)

| Select demographic characteristics | ESS* ≤ 10, n=536 | ESS* > 10, n=107 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.42 (14.6) | 54.36 (13.3) | 0.19 |

| History of hysterectomy, n (%) | 161 (30.0) | 32 (29.9) | 0.98 |

| Not currently menstruating, n (%) | 382 (71.5) | 75 (70.1) | 0.76 |

| Current diuretic use, n (%) | 80 (14.9) | 23 (21.5) | 0.09 |

| Current estrogen use, n (%) | 44 ( 8.2) | 9 ( 8.4) | 0.95 |

| Current cigarette smoking, n (%) | 79 (14.7) | 13 (12.3) | 0.51 |

| Current weekly alcohol use, n (%) | 168 (31.4) | 27 (25.2) | 0.20 |

| Excellent or very good overall health **, n (%) | 432 (80.6) | 74 (69.2) | 0.008 |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms, per day | |||

| Total incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 4.63 ( 3.3) | 4.94 ( 4.0) | 0.89 |

| Total urgency incontinence episodes, mean (SD) | 3.86 ( 2.8) | 4.11 ( 3.3) | 0.94 |

| Total daytime incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 3.98 ( 2.7) | 4.30 ( 3.4) | 0.89 |

| Total nighttime incontinent episodes, mean (SD) | 0.65 ( 1.0) | 0.64 ( 1.1) | 0.70 |

| Total micturitions, mean (SD) | 10.00 ( 3.3) | 10.15 ( 3.3) | 0.59 |

| Total daytime micturitions, mean (SD) | 8.73 ( 2.9) | 8.84 ( 3.0) | 0.65 |

| Total nighttime micturitions, mean (SD) | 1.27 ( 1.3) | 1.31 ( 1.3) | 0.50 |

| Total severe urgency sensation, mean (SD) | 3.51 ( 3.3) | 3.95 ( 4.1) | 0.55 |

ESS is a self-reported scale that assess daytime sleepiness and assess the participant’s probability of falling asleep in eight different situations on a sale from 0–3 with a total score from 0 to 24. Score > 10 are indicative of significant daytime sleepiness.

Participants reported their perceptions of their overall health status as poor, satisfactory, good, very good or excellent

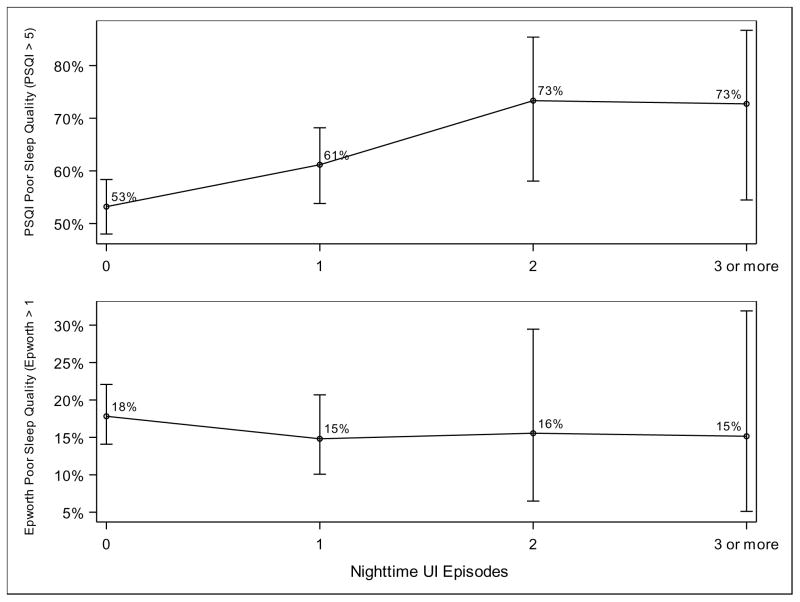

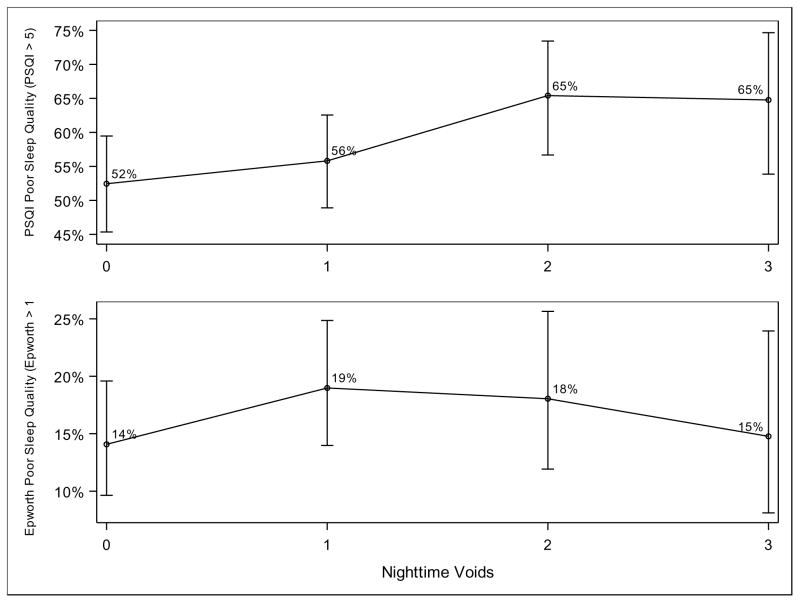

We also analyzed the strength of the relationship between lower urinary tract symptoms and poor quality sleep. Test for linear trend using one degree of freedom found a positive relationship between poor sleep quality according to the PSQI and increasing total urgency urinary incontinence episodes per night, p=0.01 (Figure 1). For example, 73% of participants with three episodes of urgency incontinence per night met the threshold for poor sleep quality, as opposed to 53% of participants with one episode per night. We similarly found a significant relationship between poor sleep quality according to the PSQI and increasing voids per night, p=0.02 (Figure 2). A total of 65% of participants with three episodes of nocturia per night met the threshold for poor sleep quality, as opposed to 52% of participants with no episodes of nocturia. We did not find a significant relationship between either frequency of nighttime urgency incontinence episodes or nocturia and daytime sleepiness as measured by the ESS.

Figure 1.

Poor sleep quality and total urgency urinary incontinence episode per night

Test for linear trend using one degree of freedom found a positive relationship between poor sleep quality according to the PSQI and increasing total urgency urinary incontinence episodes per night, p=0.01. There was no significant relationship between daytime sleepiness according to the ESS and increasing nighttime urgency urinary incontinence episodes per night. Results are controlled for clinical site and smoking status.

Figure 2.

Poor sleep quality and night time voids per night

Test for linear trend using one degree of freedom found a positive relationship between poor sleep quality according to the PSQI and increasing voids per night, p=0.02. There was no significant relationship between daytime sleepiness according to the ESS and increasing voids per night. Results are controlled for clinical site and smoking status.

In a multivariable analysis controlling for different lower urinary tract symptoms, only nighttime urgency incontinence remained significantly associated with PSQI (p=0.03, data not shown). Subset analysis was completed excluding those who use sleeping medication regularly (≥3 times per week). The results for this analysis were similar to those in the entire cohort.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the high prevalence of poor sleep quality among women with urgency urinary incontinence and provides new evidence that the severity of incontinence correlates with the degree of sleep disturbance. Because poor sleep quality has been associated with depression,20 dementia,21 cardiovascular disease22 and mortality,23,24 it is important to identify individuals with poor sleep in order to refer them to appropriate treatment.

Nocturia is one of the most common reasons for waking up at night25 and a number of studies have demonstrated a correlation between nocturia and poor sleep quality.26–30 These studies, however, have tended to focus specifically on elderly populations where nocturia is most common with less attention to reproductive-age and midlife women. Moreover these studies have not consistently examined other measures of incontinence that also may have the potential to influence sleep outcomes among women in the community.

This study is unique in that it assesses a wide variety of incontinence measures demonstrating that not only are nighttime incontinence episodes and nighttime micturition associated with poor sleep quality, but daytime incontinence and daytime urgency episodes are similarly associated with poor quality sleep. In a multivariable model controlling for lower urinary tract symptoms, only nighttime urgency incontinence was significantly associated with PSQI suggesting that nighttime urgency urinary incontinence is the primary driver of poor quality sleep.

Although we examined both sleep quality using the PSQI and daytime sleepiness with the ESS we found that our incontinence measures were correlated only with sleep quality using the PSQI. Prior studies have demonstrated an association between nocturia and ESS score.31 It is possible that we did not see a significant relationship between ESS score and incontinence measures due to limited sample size since the study was not powered specifically to address daytime sleepiness. While not statistically significant, there was a non-significant trend toward greater daytime sleepiness with increasing frequency of incontinence. It is also possible that we may not have found a significant relationship between daytime sleepiness and nocturia because the frequency of lower urinary tract symptoms was common in our population and there were very few respondents with no or minimal nocturia. Our results may therefore demonstrate a ceiling effect.

In addition to incontinence measures, other demographic characteristics including smoking status were found to be associated with poor sleep quality. Characteristics that have previously been associated with poor quality sleep include poor overall health32,33 and sleep apnea.34,35 Similarly, it was observed that respondents who reported poor overall health were more likely to report poor sleep quality. While we did not specifically assess sleep apnea, it has been suggested that smoking is a risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing such as sleep apnea36 and our study did find that current cigarette smoking was associated with worse quality sleep.

The major strengths of this study include a large sample size with information on multiple demographic and clinical characteristics as well as detailed information about a variety of urinary tract symptoms. There are several limitations to our study. This study looked specifically at women with urgency-predominant urinary incontinence and excluded patients with stress only or stress-predominant mixed incontinence or those with urinary urgency in the absence of incontinence and our results may not be generalizable to these populations. This study also excluded participants with major comorbidities that might warrant further evaluation by an urogynecologist prior to initiation of pharmacologic therapy, therefore our population may not be entirely generalizable.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the overall high prevalence of abnormal sleep among those with urgency urinary incontinence and suggests that worsening urgency urinary incontinence is associated with worse quality sleep. Given the known adverse effects of poor quality sleep on health outcomes and quality of life, it is important that healthcare providers who are treating patients with incontinence inquire about their sleeping habits so that they can be offered appropriate treatment or referrals. In addition, treating incontinence may also help improve sleep quality among women with both bothersome conditions.

Acknowledgments

Sources/Funding: Pfizer, Inc, provided funding for the study and the study medication but did not provide other input into the design of the study; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication. LLS was additionally supported by grant 2K24DK080775-06 from the US National Institutes of Health; however, the views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: None

Author Disclosures Statement: Drs. Subak, Brown and Huang have received a University of California San Francisco research grant from Pfizer, Inc, to conduct research related to urinary incontinence. Pfizer, Inc, provided funding for the study and the study medication but did not provide other input into the design of the study; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Dr. Subak is additionally supported by NIDDK K24 DK080775. Dr. Subak had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. No manuscript preparation assistance was provided by the study funders.

Drs. Subak and Huang receive investigator-initiated trial funding from Astellas, Inc. Dr. Huang was additionally supported by grants RR024130 and 1K23AG038335-01A1 and Dr. Subak from 2K24DK080775-06 from the US National Institutes of Health; however, the views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Arya has received a research grant from Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Richter has received a research grant and is a consultant for Pelvalon and receives royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Bradley has served as a consultant for Astellas and for GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Kraus has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Inc, and Allergan and has been a course director and teaching faculty member for Laborie. Dr. Rogers, receives royalties from UptoDate, and served as the DSMB chair for the TRANSFORM trial sponsored by American Medical Systems.

References

- 1.Offermans MPW, Du Moulin MFMT, Hamers JPH, Dassen T, Halfens RJG. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated risk factors in nursing home residents: a systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:288–294. doi: 10.1002/nau.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris SS, Link CL, Tennstedt SL, Kusek JW, McKinlay JB. Care seeking and treatment for urinary incontinence in a diverse population. J Urol. 2007;177(2):680–684. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Hunskaar S. Help-seeking and associated factors in female urinary incontinence. The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trøndelag. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2002;20(2):102–107. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12184708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrill M, Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Nager CW, Contreras R, Luber KM. Seeking healthcare for pelvic floor disorders: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):86.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herzog AR, Diokno AC, Brown MB, Fultz NH, Goldstein NE. Urinary incontinence as a risk factor for mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(3):264–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01749.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8120310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101(11):1388–1395. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103(Suppl):4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotoh M, Matsukawa Y, Yoshikawa Y, Funahashi Y, Kato M, Hattori R. Impact of urinary incontinence on the psychological burden of family caregivers. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(6):492–496. doi: 10.1002/nau.20675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch JLHR, Weiss JP. The prevalence and causes of nocturia. J Urol. 2013;189(1 Suppl):S86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentili A, Weiner DK, Kuchibhatil M, Edinger JD. Factors that disturb sleep in nursing home residents. Aging (Milano) 1997;9(3):207–213. doi: 10.1007/BF03340151. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9258380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colten H, Altevogt B, et al., editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20669438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu A, Nakagawa S, Walter LC, et al. The burden of nocturia among middle-aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):35–43. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang AJ, Hess R, Arya LA, et al. Pharmacologic treatment for urgency-predominant urinary incontinence in women diagnosed using a simplified algorithm: A randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012:206. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2748771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1798888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(6):563–571. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19110886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown JS, McNaughton KS, Wyman JF, et al. Measurement characteristics of a voiding diary for use by men and women with overactive bladder. Urology. 2003;61(4):802–809. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02505-0. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12670569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Kopp Z, Abrams P. The validation of the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC): a single-item global measure for patients with overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2006;49(6):1079–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyne K, Revicki D, Hunt T, et al. Psychometric validation of an overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire: the OAB-q. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(6):563–574. doi: 10.1023/a:1016370925601. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12206577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama E, Kaneita Y, Saito Y, et al. Association between depression and insomnia subtypes: a longitudinal study on the elderly in Japan. Sleep. 2010;33(12):1693–1702. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.12.1693. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21120150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cricco M, Simonsick EM, Foley DJ. The impact of insomnia on cognitive functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(9):1185–1189. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49235.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11559377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldstein CA. Nocturia in arterial hypertension: a prevalent, underreported, and sometimes underestimated association. J Am Soc Hypertens. 7(1):75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dew MA, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, et al. Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosom Med. 65(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000039756.23250.7c. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12554816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eaker ED, Pinsky J, Castelli WP. Myocardial infarction and coronary death among women: psychosocial predictors from a 20-year follow-up of women in the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(8):854–864. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116381. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1585898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bing MH, Moller LA, Jennum P, Mortensen S, Skovgaard LT, Lose G. Prevalence and bother of nocturia, and causes of sleep interruption in a Danish population of men and women aged 60–80 years. BJU Int. 2006;98(3):599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obayashi K, Saeki K, Kurumatani N. Quantitative association between nocturnal voiding frequency and objective sleep quality in the general elderly population: the HEIJO-KYO cohort. Sleep Med. 2015;16(5):577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asplund R. Nocturia in relation to sleep, somatic diseases and medical treatment in the elderly. BJU Int. 2002;90(6):533–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02975.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12230611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coyne KS, Zhou Z, Bhattacharyya SK, Thompson CL, Dhawan R, Versi E. The prevalence of nocturia and its effect on health-related quality of life and sleep in a community sample in the USA. BJU Int. 2003;92(9):948–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04527.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14632853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gopal M, Sammel MD, Pien G, et al. Investigating the associations between nocturia and sleep disorders in perimenopausal women. J Urol. 2008;180(5):2063–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rembratt A, Norgaard JP, Andersson K-E. Nocturia and associated morbidity in a community-dwelling elderly population. BJU Int. 2003;92(7):726–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04467.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14616455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shao I-H, Wu C-C, Hsu H-S, et al. The effect of nocturia on sleep quality and daytime function in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: a cross-sectional study. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:879–885. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S104634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H-S, Li Y, Mo H-Y, et al. A community-based cross-sectional study of sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults. Qual Life Res. 2016 Sep; doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang C-Y, Chiou A-F. Predictors of sleep quality in community-dwelling older adults in Northern Taiwan. J Nurs Res. 2012;20(4):249–260. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182736461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umlauf MG, Chasens ER, Greevy RA, Arnold J, Burgio KL, Pillion DJ. Obstructive sleep apnea, nocturia and polyuria in older adults. Sleep. 2004;27(1):139–144. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.139. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14998251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pressman MR, Figueroa WG, Kendrick-Mohamed J, Greenspon LW, Peterson DD. Nocturia. A rarely recognized symptom of sleep apnea and other occult sleep disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(5):545–550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.5.545. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8604961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trenchea M, Deleanu O, Suţa M, Arghir OC. Smoking, snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Pneumologia. 62(1):52–55. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23781575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]