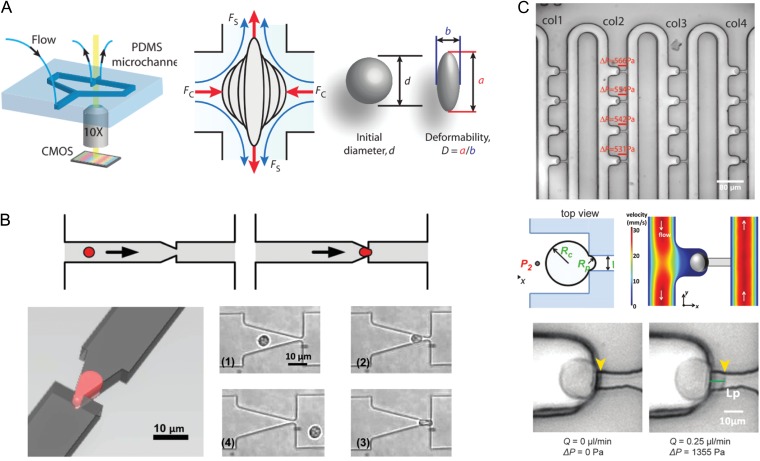

Figure 3.

Devices for automated and high-throughput microfluidic mechanical characterization, which could be adapted to measure embryos and oocytes. (A) Hydrodynamic cell stretcher to measure deformability parameter (Tse et al., 2013). The left side of the image shows the microfluidic chip, which contains a channel that contains cells to be tested and a perpendicular channel to stretch them under continuous flow. The middle part of the image shows a schematic of a single cell being stretched, where it is subjected to a compressive (FC) and a shear (FS) force. The right part of the image shows how a ‘deformability’ parameter is calculated. (B) Micropipette aspiration translated to a microfluidic chip (Guo et al., 2012). The top panels show a schematic of a single cell being deformed to simulate micropipette aspiration, and the left panel shows the aspiration process from another angle. The panels numbered (1) through (4) show micrographs of a single neutrophil as it is deformed through a funnel constriction. (C) Device that can autonomously perform micropipette aspiration on many cells simultaneously (Lee and Liu, 2015). The top panel shows loading of single cells into columns with individual trapping structures. The middle left panel shows a schematic of a single cell undergoing aspiration, where RC is the radius of the cell and RP is the radius of the aspiration micropipette. The middle right panel shows a numerical simulation of the flow velocity around the cell. The bottom panels show a demonstration of micropipette aspiration using the device.