Abstract

Women with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation (LT) experience higher rates of waitlist mortality than men; it is unknown whether practices surrounding delisting for being “too sick” for LT contribute to this disparity beyond death alone. We conducted an analysis of patients listed for LT in the United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network not receiving exception points from May 1, 2007 to July 1, 2014 with a primary outcome of delisting with removal codes of “too sick” or “medically unsuitable.” A total of 44 388 patients were included; 4458 were delisted for being “too sick” for LT. Delisting was more frequent in women (11% vs 9%, P < .001). Compared to delisted men, delisted women differed in age (58 vs 57), non–hepatitis C virus listing diagnoses (69% vs 56%), hepatic encephalopathy (36% vs 31%), height (161.9 vs 177.0 cm), private insurance (47% vs 52%), and Karnofsky performance status (60 vs 70) (P < .001 for all). There were no differences in Model for End-Stage Liver Disease including serum sodium and Child Pugh Scores. A competing risk analysis demonstrated that female sex was independently associated with a 10% (confidence interval 2%–18%) higher risk of delisting when accounting for rates of death and transplantation and adjusting for confounders. This study demonstrates a significant disparity in delisting practices by sex, highlighting the need for better assessments of sickness, particularly in women.

Keywords: cirrhosis, clinical research/practice, disparities, liver transplantation/hepatology

1 | INTRODUCTION

The decision to delist a patient for being “too sick” for liver transplantation has profound clinical, social, and emotional effects. In theory, the decision is a surrogate clinical assessment that liver transplantation poses too great a risk and should not be pursued despite the severity of liver disease. Several clinical parameters are often considered: advanced age, acute on chronic liver failure, sarcopenia, and non-liver-related medical comorbidities.1 There are no strict criteria for delisting, and this decision relies on clinical consensus of all members of a transplant team.

Current literature evaluating disparities in liver transplantation has focused largely on the combined outcome of death and delisting for being “too sick.” This work has demonstrated that women are underserved by the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELDNa) score.2 The reasons for this disparity include height, inaccurate measures of renal function, sarcopenia, and liver volume.3–7 We hypothesized that the magnitude of this disparity was exacerbated by disproportionate delisting of women relative to men, perhaps due in part to differing perceptions of a greater degree of frailty, inadequate social support, or smaller stature.

Herein, we present a study focused solely on delisting for being “too sick” for liver transplantation, a different outcome than death on the waitlist. Our study seeks to better characterize those patients being delisted for being “too sick” for liver transplantation, identifying disparities in delisting, particularly by sex.

2 | METHODS

All patients listed for single-organ liver transplantation in the United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (UNOS/OPTN) registry from May 1, 2007 through July 1, 2014 were evaluated for inclusion in this study. This timeframe was chosen to produce a contemporary cohort with enough follow-up time to make an assessment of postdelisting survival. Patients who were <18 years old or listed as Status 1, including those with fulminant hepatic failure, were excluded. Due to varying likelihood and timing of receiving a transplant, those who received MELD exception points or underwent a living donor liver transplantation were also excluded.

2.1 | Covariates

Data were obtained from the UNOS/OPTN registry as of March 31, 2016. Data included sex, age at listing, race, height, weight, ABO group, UNOS region,1–11 date of listing, listing diagnoses, death date, date of removal from the waitlist, reason for removal, transplant date, insurance status, and Karnofsky performance status (KPS). The following data were collected at listing and delisting: total bilirubin, international normalized ratio (INR), serum creatinine, presence of hepatic encephalopathy, and presence of ascites. Cutoffs deemed to be implausible were as follows: height <120 and >240 cm, weight <30 and >180 kg, total bilirubin ≤ 0 mg/dL, INR ≤ 0, and creatinine ≤ 0 mg/dL. MELDNa was calculated using the standard formula using a lower limit of 1 for all variables.8 The lower and upper limits of 6 and 40 were used to mimic standard practice.

UNOS region of listing was categorized by median calculated MELD scores with exception points at transplantation into low (regions 3, 10, 11; median MELD 22), medium (regions 2, 4, 6, 8, 9; median MELD 25), and high (regions 1, 5, 7; median MELD 28) risk regions.3,9 These medians were determined from the study period, excluding those who had a listing diagnosis of acute liver failure or a removal code of living donor liver transplant. Listing diagnoses were grouped into the following common diagnostic categories: hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (including cryptogenic cirrhosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis), alcoholic cirrhosis, autoimmune causes (including primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis), and other causes of cirrhosis (any other listing code that met inclusion criteria). KPS was categorized by established cutoffs: able to carry on normal activity (KPS of 80–100), unable to work but able to live at home (KPS of 50–70), and unable to care for self (KPS of 10–40).10

2.2 | Outcomes and censoring

The primary outcome in this study was delisting for being too sick for liver transplantation, defined as reported reason for waitlist removal of “medically unsuitable” or “too sick for transplant” in the UNOS database (removal codes 5 and 13, respectively). We sought to examine the association between sex and being deemed too sick for liver transplantation. Patient follow-up began on the date of listing and ended at the time of death, removal from the waitlist, or transplant. Those removed from the waitlist were followed to last data update with special attention when death occurred by cross-referencing the UNOS/OPTN waitlist and the Social Security Death Master File. In order to determine what affected survival after delisting, patients with a death that occurred within 30 days of delisting were defined as an “early death” and those with a death after 30 days from delisting were defined as a “late death.”

2.3 | Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared between groups by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were compared between groups by the χ2 test.

Unadjusted models were used to assess the association of all listed covariates. All covariates with a P < .2 in univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in multivariate models. Those not reaching significance of P < .05 were sequentially eliminated. Competing risks analysis was used in assessing the association between sex and other covariates with the primary outcome. In this analysis using the Fine-Gray model, removal from the waitlist for being too sick, removal for improvement, death, and transplantation were treated as competing risks.11 Patients who remained alive on the waitlist at the end of follow-up were conventionally censored at the date of the most recent update of the UNOS registry, because they remained at risk for delisting for being too sick. Adjusted cumulative incidence was also estimated based on the competing risk model. This competing risk analysis was used to assess the influence of sex and other covariates on the likelihood of being delisted for being too sick.

Two-sided P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Stata 13.0 statistical software (College Station, TX). This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco.

3 | RESULTS

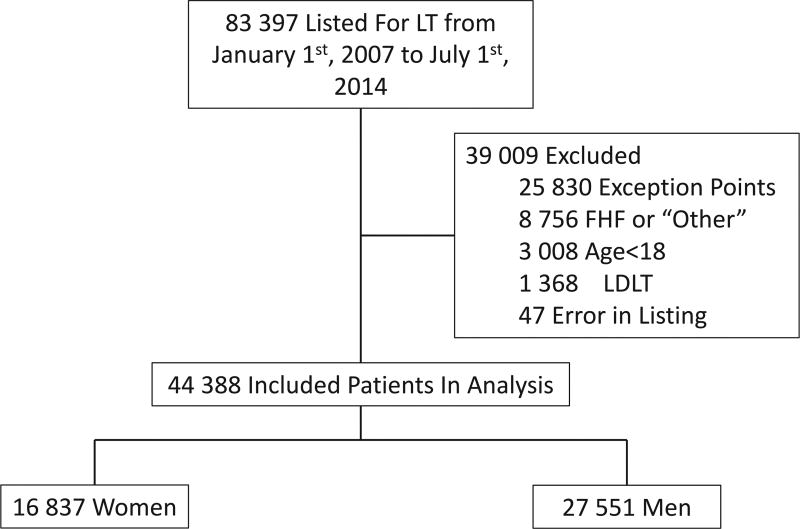

From May 1, 2007 through July 1, 2014, 83 397 patients were listed for liver transplantation through the UNOS registry. Of the 44 388 patients included in this study, 27 551 (62%) were men and 16 837 (38%) were women (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared to men, women were older (56 vs 55 years, P < .001) and were on the waitlist for longer (213 vs 175 days, P < .001). They were more likely to have a non-HCV listing diagnosis (70 vs 58%, P < .001) and have hepatic encephalopathy (18% vs 17%, P < .001). Women were less likely to have ascites (37% vs 42%, P < .001) and private insurance (54% vs 58%, P < .001). MELDNa at listing (19 vs 20, P < .001) and at delisting (24 vs 24, P < .001) were clinically similar though statistically lower in women compared to men.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of patients listed for liver transplantation. FHF, fulminant hepatic failure; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients listed for liver transplantation in the United States from May 1, 2007 to July 1, 2014

| Women (n = 16 837) |

Men (n = 27 551) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at listing, median (IQR) | 56 (49–61) | 55 (49–60) | <.001 |

| Listing diagnosis, no. (%) | |||

| HCV | 5072 (30) | 11 511 (42) | <.001 |

| Alcohol | 2426 (15) | 6945 (25) | <.001 |

| NAFLD/NASH | 4484 (26) | 4774 (17) | <.001 |

| Autoimmunea | 3564 (21) | 2321 (8) | <.001 |

| Other | 1291 (8) | 2000 (8) | .57 |

| Non-Hispanic white, no. (%) | 11 781 (70) | 20 326 (74) | <.001 |

| Height in cm, median (IQR) | 163 (157–168) | 178 (173–183) | <.001 |

| Ascites, no. (%) | 6306 (37) | 11 499 (42) | <.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy, no. (%) | 3034 (18) | 4688 (17) | <.001 |

| MELDNa at listing, median (IQR) | 19 (14–27) | 20 (15–27) | <.001 |

| MELDNa at delisting, median (IQR) | 24 (16–33) | 24 (17–33) | <.001 |

| Days on waitlist, median (IQR) | 213 (31–804) | 175 (28–731) | <.001 |

| Karnofsky performance status category, no. (%) | |||

| Unable to care for self | 3731 (22) | 5786 (21) | |

| Unable to work | 7213 (43) | 11 571 (42) | <.001 |

| Normal activity | 5893 (35) | 10 194 (37) | |

| Private insurance, no. (%) | 9151 (54) | 16 005 (58) | <.001 |

| Region risk, no. (%) | |||

| Low | 4883 (29) | 8265 (30) | |

| Medium | 6903 (41) | 11 020 (40) | .22 |

| High | 5051 (30) | 8266 (30) | |

| ABO group | |||

| A, no. (%) | 6165 (37) | 10 566 (38) | |

| B, no. (%) | 2022 (12) | 3261 (12) | .002 |

| AB, no. (%) | 628 (4) | 1051 (4) | |

| O, no. (%) | 8022 (47) | 12 673 (46) | |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; IQR, interquartile range; no., number; MELDNa, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease including serum sodium; NAFLD/NASH, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

During the follow-up period, more women than men were removed from the waitlist for being too sick for liver transplantation (11% vs 9%; P < .001). There were also statistically significant sex differences in other waitlist outcomes: 3095 (18%) women and 4659 (17%) men died (P < .001); 7284 (43%) women and 13 444 (49%) men received a deceased donor liver transplant (P < .001); 985 (6%) women and 1232 (4%) men improved (P < .001); 3590 (21%) women and 5641 (20%) men remained on the waitlist (P < .001).

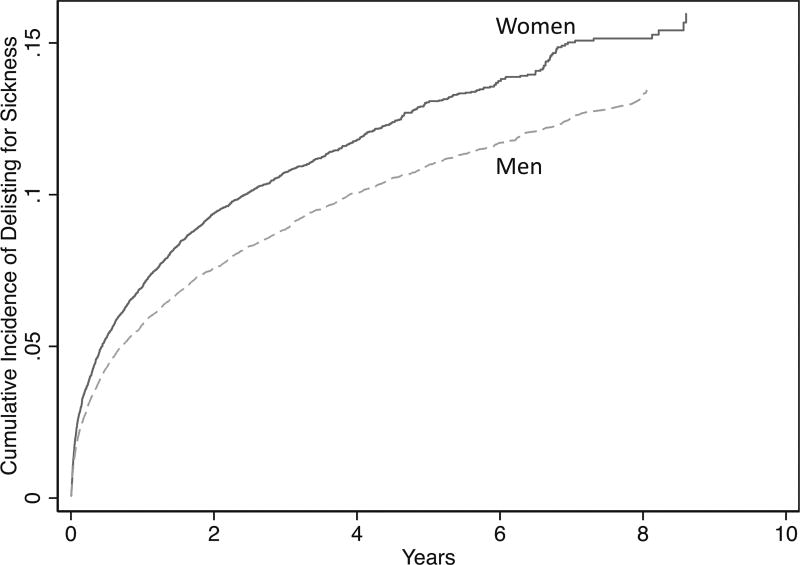

To better understand why women were more frequently removed from the waitlist for being too sick, we compared women delisted for being too sick to men delisted for being too sick. Delisted women were significantly older (58 vs 57 years, P < .001), shorter (161.9 vs 177.0 cm, P < .001), had a higher prevalence of non-HCV listing diagnoses (69% vs 56%, P < .001), and had a higher prevalence of hepatic encephalopathy (36% vs 31%, P < .001) than delisted men. Delisted women were less likely to have private insurance (47% vs 52%, P < .001). A greater proportion of delisted women were in the lowest functioning category (KPS 10–40; unable to care for self) when compared to delisted men (26% vs 22%, P < .001). Conversely, a greater proportion of delisted men were in the “normal activity” category (35% vs 30%, P < .001). There were no differences in MELDNa at listing or delisting (19 vs 19, P = .65; 28 vs 27, P = .21). There were no differences in waitlist time by sex (218 vs 228 days, P = .20) (Table 2). There were significant differences in the proportion of women delisted by center (P < .001). The difference between delisting MELDNa and listing MELDNa was equal between sexes (5 points vs 4 points, P = .14), suggesting similar rates of hepatic decompensation. The increased cumulative incidence of waitlist removal for being too sick in women is shown in Figure 2.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of patients removed from the waitlist for being deemed too sick for liver transplantation

| Delisted women (n = 1883) |

Delisted men (n = 2575) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at listing (y), median (IQR) | 58 (53–63) | 57 (52–62) | <.001 |

| Listing diagnosis, no. (%) | |||

| HCV | 582 (31) | 1139 (44) | <.001 |

| NAFLD/NASH | 582 (31) | 480 (19) | <.001 |

| Autoimmunea | 359 (19) | 155 (6) | <.001 |

| Alcohol | 239 (13) | 652 (25) | <.001 |

| Other | 121 (6) | 149 (6) | .38 |

| Non-Hispanic white, no. (%) | 1301 (69) | 1836 (71) | .11 |

| Height in cm, median (IQR) | 162 (157–166) | 177 (170–183) | <.001 |

| Ascites, no. (%) | 895 (48) | 1263 (49) | .33 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy, no. (%) | 672 (36) | 802 (31) | .001 |

| MELDNa at listing, median (IQR) | 19 (14–27) | 19 (15–26) | .62 |

| MELDNa at delisting, median (IQR) | 28 (20–37) | 27 (19–37) | .21 |

| Days on waitlist, median (IQR) | 218 (44–627) | 228 (49–671) | .20 |

| Karnofsky performance status category, no. (%) | |||

| Unable to care for self | 497 (26) | 576 (22) | |

| Unable to work | 824 (44) | 1103 (43) | <.001 |

| Normal activity | 562 (30) | 896 (35) | |

| Private insurance, no. (%) | 16 005 (47) | 9151 (52) | <.001 |

| Region risk, no. (%) | |||

| Low | 417 (22) | 545 (21) | |

| Medium | 850 (45) | 1198 (47) | .61 |

| High | 616 (33) | 832 (32) | |

| ABO group | |||

| A, no. (%) | 710 (38) | 1021 (40) | |

| B, no. (%) | 217 (12) | 248 (10) | .02 |

| AB, no. (%) | 24 (1) | 56 (2) | |

| O, no. (%) | 932 (49) | 1250 (48) | |

IQR, interquartile range; no., number; MELDNa, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease including serum sodium; NAFLD/NASH, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative incidence of removal from the waitlist for being too sick

A competing risks analysis was completed to determine whether the association between sex and delisting was independent of other variables associated with delisting. In univariate analyses, the following were significantly associated with removal from the waitlist for being too sick: age per year (subhazard ratio [SHR] 1.04, P < .001), female sex (SHR 1.21, P < .001), diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis (SHR 0.81, P < .001), presence of ascites (SHR 2.31, P < .001), presence of hepatic encephalopathy (SHR 3.46, P < .001), MELDNa at listing (SHR 1.01, P < .001), MELDNa at delisting (SHR 1.03, P < .001), height per 10 cm (SHR 0.92, P < .001), KPS category unable to work (SHR 0.87, P < .001), KPS category normal activity (SHR 0.73, P < .001), and having private insurance (SHR 0.75, P < .001). Listing center was not significantly associated with delisting (P = .26). Multivariable adjustment for the significant potential confounders did not change the significant association between female sex and delisting for being too sick for liver transplantation; women were 10% more likely to be removed from the waitlist for being too sick for liver transplantation (P < .001) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Competing risk analysis for delisting for being too sick

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| SHR | 95% CI | P | SHR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age per year | 1.04 | 1.03–1.04 | <.001 | 1.03 | 1.03–1.04 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Female sex | 1.21 | 1.14–1.29 | <.001 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.18 | .01 |

|

| ||||||

| Autoimmunea | 0.81 | 0.75–0.89 | <.001 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Ascites | 2.31 | 2.19–2.44 | <.001 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 3.46 | 3.27–3.67 | <.001 | 2.02 | 1.88–2.16 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Serum creatinine at listing per 1mg/dL | 1.15 | 1.14–1.17 | <.001 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Height per 10cm | 0.92 | 0.90–0.94 | <.001 | 0.97 | 0.94–0.99 | .02 |

|

| ||||||

| MELDNa at listing per point | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | <.001 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| MELDNa at delisting per point | 1.03 | 1.03–1.03 | <.001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.03 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Karnofsky performance status category | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Unable to care for self | — | — | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||

| Unable to work | 0.87 | 0.81–0.94 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.87–1.04 | .28 |

|

| ||||||

| Normal activity | 0.73 | 0.68–0.79 | <.001 | 0.85 | 0.77–0.94 | .001 |

|

| ||||||

| Region risk | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | — | — | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||

| Medium | 1.54 | 1.42–1.66 | <.001 | 1.43 | 1.33–1.54 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| High | 1.50 | 1.38–1.62 | <.001 | 1.41 | 1.30–1.53 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Private insurance | 0.74 | 0.70–0.79 | <.001 | 0.83 | 0.78–0.88 | <.001 |

CI, confidence interval; MELDNa, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease including serum sodium; SHR, subhazard ratio.

Autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

After identifying that women were more frequently removed from the liver transplantation waitlist for being too sick, an analysis was completed to determine whether outcomes after delisting (ie time to death) varied by sex. Of the 4458 patients removed from the waitlist for being too sick, 1355 (30%) died within 30 days of delisting (“early” death). The same proportion of women and men had an “early death” (30% vs 31%, P = .40). There was no difference in length of survival between women who were delisted and men who were delisted (39 vs 46 days, P = .34). Further, among individuals with a KPS score 0–40 (ie, those who were most frail) who underwent liver transplantation, there were no differences in survival after liver transplantation between women and men (852 vs 912 days, P = .14). Despite this, women with a KPS score of 0–40 were disproportionately delisted for being too sick as compared with men with a KPS score of 0–40 (13% vs 10%, P < .001). Those who died within 30 days of delisting had higher rates of HCV (42% vs 38%, P = .01), ascites (60% vs 43%, P < .001), and hepatic encephalopathy (46% vs 28%, P < .001). These patients were more likely to be non-Hispanic white (73% vs 69%, P = .02), have higher MELDNa scores at listing (23 vs 18, P < .001), have higher MELDNa scores at delisting (33 vs 25, P < .001), shorter time on the waitlist (96 days vs 335 days, P < .001), and more likely to be in the KPS category “unable to care for self” (30% vs 22%, P < .001).

4 | DISCUSSION

While multiple studies have demonstrated sex-based disparities in waitlist mortality, these studies have evaluated only the combined outcome of death and delisting for being too sick for liver transplantation.2,4 This is logical, as delisting, for a decompensated cirrhotic patient, essentially translates into near-certain death from end-stage liver disease. However, evaluating this outcome as a combination of the clinical endpoints has not allowed the transplant community to isolate the specific contribution of variable delisting practices to these sex-based disparities. Given that there are no objective or standardized criteria for delisting, this leaves open the possibility that differences in delisting practices for women versus men on the liver transplant waitlist have contributed to these reported disparities.

In this study evaluating rates of delisting from the US liver transplant waitlist, we demonstrate that there are significant sex-based disparities in delisting practices. Women were 10% more likely to be delisted than men. This translated into an absolute difference in the rates of delisting of 2%. Assuming that women and men experience the same rates of hepatic decompensation and death from cirrhosis (outside of the transplant setting), then an additional 692 women were removed from the waitlist than would have been expected had they been men. This disparity persisted despite adjustment for other factors known to be associated with sickness and transplant rates: age, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, MELDNa score, height, and performance status. These disproportionate delisting practices occurred despite similar survival after delisting.

We offer the following explanations of our results. First, it is possible that women are perceived to be frailer than men. In our study, delisted women were significantly more likely to be in the lowest KPS category, while men were more likely to be in the highest KPS category. This suggests that if perceptions of frailty are impacting delisting, it is having a greater effect on woman than on men, despite no differences in survival after delisting. Second, women are more likely to have longer wait times, due to lower MELD scores,4 and higher likelihood of declining a liver offer (primarily due to small stature).12 We propose that this creates a harmful cycle in which women who remain on the waitlist longer have a progressive decline in clinical and functional status and ultimately are more frequently deemed to be “too sick” for liver transplantation. It is our argument that this cycle demonstrates the need for universal, accurate criteria to better capture sickness in patients on the waitlist.

There are limitations to our study. The accuracy of this study is subject to the utilization of appropriate coding in the UNOS registry. There is known variability in removal codes used by OPTN regions. However, by cross-referencing with the Social Security Administration, as done in this study, the variability can be improved.13 This is imperfect and men may have slightly more frequently misclassified removal codes than women.14 However, this marginal increase in misclassifying men is unlikely to explain the significant disparities in delisting by sex demonstrated in this study and the disparities demonstrated in other studies looking at waitlist mortality.2,4,12 Next, this study represents a large cohort with the statistical power to make clinically insignificant differences statistically significant. The absolute difference in delisting between men and women in this study represents roughly 97 lives per year. For reference, the use of the MELDNa rather than MELD score corrects roughly 32 patients per year.8 Therefore, we argue that even a 2% difference has significant clinical implications and efforts should be made to correct this disparity.

Despite these limitations, this is an early study describing the delisting practices in the UNOS registry. There is a clear disparity by sex that persists despite controlling for known confounders. Future studies should focus on the social, behavioral, and non-liver-related factors that lead to more frequent practices of removing women from the waitlist.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by an American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award, P30AG044281 (UCSF Older Americans Independence Center), K23AG048337 (Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research), and P30 DK026743 (UCSF Liver Center). These funding agencies played no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- KPS

Karnofsky performance status

- MELDNa

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease including serum sodium

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.Lai JC. Defining the threshold for too sick for transplant. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2016;21(2):127–132. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Alastair D, Tuttle-newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD score. JAMA. 2013;300(20):2371–2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai JC, Terrault NA, Vittinghoff E, Biggins SW. Height contributes to the gender difference in wait-list mortality under the MELD-based liver allocation system. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2658–2664. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Sex-based disparities in liver transplant rates in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(7):1435–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mindikoglu AL, Emre SH, Magder LS. Impact of estimated liver volume and liver weight on gender disparity in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(1):89–95. doi: 10.1002/lt.23553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mindikoglu AL, Regev A, Seliger SL, Magder LS. Gender disparity in liver transplant waiting-list mortality: The importance of kidney function. Liver Transplant. 2010;16(10):1147–1157. doi: 10.1002/lt.22121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar M, Watt KD, Terrault N, Berenguer M. Outcomes in liver transplantation: Does sex matter? J Hepatol. 2015;62:946–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):1018–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai JC, Feng S, Vittinghoff E, Roberts JP. Offer patterns of nationally placed livers by donation service area. Liver Transplant. 2013;19(4):404–410. doi: 10.1002/lt.23604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandon P, Reddy KR, O’Leary JG, et al. A Karnofsky performance status-based score predicts death after hospital discharge in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):217–224. doi: 10.1002/hep.28900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine JP, Gray RJ. Proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk a proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 2013;1999(1459):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nephew LD, Goldberg DS, Lewis JD, Abt P, Bryan M, Forde KA. Exception points and body size contribute to gender disparity in liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(8):1286–1293. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voigt MD, Hunsicker LG, Snyder JJ, Israni AK, Kasiske BL. Regional variability in liver waiting list removals causes false ascertainment of waiting list deaths. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(2):369–375. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg D, French B, Trotter J, et al. Underreporting of liver transplant waitlist removals due to death or clinical deterioration: Results at four major centers. Transplantation. 2013;96(2):211–216. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182970619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]