Abstract

Context:

There is scarce data on the prevalence of harm to adolescents from others’ use of alcohol from India.

Aims:

The aim is to study the prevalence of harm to school students from others’ alcohol use in the district of Ernakulam, Kerala and examines its psychosocial correlates among victims.

Settings and Design:

This was a cross-sectional survey of 7560 students of the age range of 12–19 years from 73 schools.

Materials and Methods:

Harm consequent to others’ drinking was assessed using a brief version of the World Health Organization–Thai Health Questionnaire on Harm to Others from Drinking. Standardized instruments were used to assess other measures.

Statistical Analysis:

The prevalence of various harms was determined. Mixed-effect logistic regression was used to explore the sociodemographic, academic, and psychological factors associated with various types of harms and odds ratios reported.

Results:

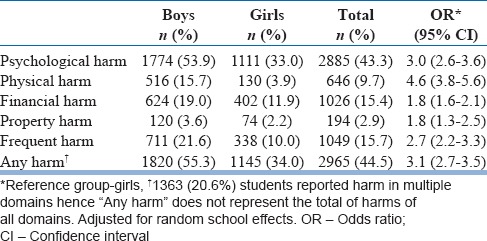

Harm due to others’ alcohol use was reported by 44.5%, frequent harm by 15.7%, psychological harm by 43.3%, physical harm by 9.7%, property harm by 2.9%, and financial harm by 15.4%. Boys reported greater harm than girls. Girls experienced relatively greater harm within the family and boys outside the family. Being older, having a part-time job and urban residence increased the odds of harm. Adolescents reporting harm had higher odds of substance use, psychological distress, suicidality, sexual abuse, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom-counts.

Conclusion:

The high prevalence of harm from others alcohol use to adolescents with multiple negative impacts underscore the urgent need for public health measures to reduce social costs of alcohol use.

Keywords: Adolescent, alcohol harm to others, correlates, epidemiology, India

INTRODUCTION

Harms from alcohol can be disaggregated into harms to the drinker and harms to others’ than the drinker. The burden of alcohol-related harm is experienced by family members, coworkers, and innocent bystanders. The types of harm can include a wide spectrum from the apparently trivial to the obviously life-threatening: injury, neglect, property damage, and public disturbances. The harms can occur in a variety of settings, which include public places, workplaces, and homes.[1,2,3,4]

Several studies, mostly from high-income countries, have described how children are verbally abused, left in unsafe situations, physically hurt, or exposed to domestic violence because of others’ drinking.[5,6,7,8,9] A recent study, draws attention to the underreporting of large numbers of Australian children who are being put at risk, due to a family member's drinking, calling it the “Hidden Harm.”[2] By and large, most of the studies have gathered their data from household studies in the general population where adults were asked whether “children for whom they had parental responsibility experienced one or more harms as a result of someone else's drinking.”[5,6,9] In the Irish National Drinking Survey of 2006, 10% of adult respondents, reported that children for whom they had parental responsibility had experienced one or more harms.[5] Similarly, in the Australian survey on alcohol's harm to others’, carers reported that the drinking of other people, including themselves, had negatively affected their children “a little” (14%) or “a lot” (3%) in the past year.[6] Among the studies from lower- and middle-income countries, in a household survey from five states in India, 43.2% of adult male respondents reported at least one alcohol-related harm (physical and psychological abuse and neglect) to children in their homes, in the past year.[9]

Self-reports from children and adolescents regarding harms suffered due to others drinking are rare in the literature. A study examining retrospective recall of adverse childhood experiences, reported that adults, with parents abusing alcohol, were at 2–13 times higher risk of having suffered multiple forms of childhood abuse and neglect.[7] In a self-reported, cross-sectional study of second-hand effects of alcohol on Vietnamese college students, 77.5% had “nonbodily effects,” and 34.2% had “bodily effects.”[8]

Accounts of adults about alcohol harm to children and adolescents under their care, especially when a significant proportion may themselves be responsible for the harms, are subject to reporting bias and likely to underestimate the problem. The experience of harms, may occur outside the home, and the adult carer may not always be informed or aware. Evidently, it is important to listen to the subjective reports of children and adolescents, to get a full measure of harms and not restrict our enquiry to the reports from adults.

Side by side, to translate into effective prevention strategies, enquiries into harms should move beyond naming and describing the negative consequences of drinking, to examining the vulnerabilities that increase likelihood of harm and the contexts in which such harms occur. In this direction, the available studies provide some preliminary direction. Older children and children from single-parent households had a greater risk of harm.[1,5,6] Female children were more likely to report alcohol-related violence and problems at home; males were more likely to report assaults, property damage, and violence in the street.[10,11,12,13,14] A qualitative study of caregivers reported that children exposed to alcohol harm had greater shame, social withdrawal, anxiety, and poorer academic performance.[10]

Previous studies have noted that substance use among adolescents might also increase their risk of suffering harms from other substance users.[8,11] As in adults, where heavy drinking among respondents, appear to significantly increase their risk of harms from others,[4,6] it is reasonable to look at the contribution of adolescent substance use as well as other factors known to increase the risk of early substance use and other high-risk behaviors, such as externalizing temperaments (including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]), adverse childhood experiences (abuse and neglect), and psychological distress.[15,16]

The consumption of alcohol in India has been dramatically increasing. The impact of this in terms of social cost is poorly studied.[17,18] This has led to great unease in the public discourse. This has been especially strident in the Southern Indian state of Kerala, which at the time of this study, had the highest per capita consumption of alcohol (8.3 liters) in India (nearly three times the national rate), with an estimated 10% of the population showing problematic drinking.[18,19]

Given the scarce data on self-reports of children and adolescents, regarding harms suffered by them from others alcohol use, from India or indeed the world, this study was undertaken in the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala, India, in a sample of adolescent schoolgoing students between the ages of 12 and 19 years. The findings reported in this paper, are secondary analyses of data from a larger study commissioned by the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) Kerala, a governmental initiative to study psychological problems among schoolgoing adolescents.

The aims of this paper were as follows:

To study the prevalence of self-reported harms from others alcohol use among schoolgoing adolescents (aged 12–19 years)

To explore factors which might increase likelihood of suffering harms from others alcohol use including sociodemographic variables, tobacco and alcohol use, externalizing temperament (ADHD symptom scores), psychological distress, sexual abuse, and suicidality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

This is a single-stage, cross-sectional, epidemiological survey conducted in 73 high and higher secondary schools in the district of Ernakulam, Kerala state, India, in 2014–2015. The 73 schools were selected by cluster random sampling from 168 schools with approximately 50,000 students. In each of the schools, a single random division of Class (year) 8, 10, and 12 was selected. The questionnaire was self-administered. School Junior Public Health Nurses (JPHNs) who had been trained previously were present to supervise the survey and to clarify doubts if any.

A total of 7560 students out of a total 7740 eligible students (97.7%) from 73 schools took part in the survey. This sample size had 95% confidence level with a margin of error of about 0.25% for an estimated prevalence rate of about 1% in this population. Of the questionnaires, 899 (12%) of questionnaires had substantial missing responses and the rest (n = 6661) were analyzed. The response rate was thus 86.4% except for one question with regards to the relationship to the person “who has harmed the participant the most in the last 1 year because of their drinking” for which the response rate was 47.8%.

Measures

Sociodemographic profile was assessed using a checklist. The questionnaire was anonymous, and hence students were not required to reveal their identity.

Harm imposed by others’ drinking

The questions assessing harm due to others drinking were extracted from the World Health Organization (WHO)–Thai Health Harm to Others from Drinking Master Protocol[20] to construct a brief screening instrument (Laslett and Room, unpublished). The domains measured in this study have been measured previously in studies from Australia, Ireland, India, and WHO country studies.[5,6,8,9]

To measure alcohol-related harms to children (hereafter to be referred to as harms), seventeen questions were asked with regards to various specific harms. Of the questions, ten questions related to physical harm, five to psychological harm (i.e., witness of serious violence and verbal abuse) and one each to property harm (i.e., physical damage to personal belongings) and financial harm (i.e., financial difficulties). The questions asked were “in the last one year, how many times, because of other's drinking, have you [experienced specific harm]?” The response options were “never,” “1–2 times,” and “3 or more times.”

In addition, the respondents were required to indicate the relationship with the person who had harmed them the most.

Substance use

A modified version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) assessed lifetime use of various psychoactive substances.[21] For the present study, we report lifetime alcohol and tobacco use. The ASSIST has good test–retest reliability and high discriminative validity.[22]

Psychological distress

Kessler's Psychological Distress Scale (K10), a screening tool for nonspecific psychological distress assessed frequency of symptoms of depression and anxiety over the past month on a 4-point Likert scale.[23] This tool has been validated in adolescents and in developing country settings including India.[24] Those scoring between 10–19 are considered to be well, 20–24 to have a mild psychological distress, 25–29 to have moderate distress, and 30–50 to have a severe distress.[23]

Suicidality

Two questions assessed lifetime suicidality: “Have you thought of committing suicide ever in your life?” and “Have you made a suicidal attempt in your lifetime?”

Sexual abuse

Four questions modified from the Child Abuse Screening Tool Children's Version (ICAST-C), an instrument which has been validated in India,[25] were asked with regards to lifetime exposure to sexual abuse: (1) Has someone misbehaved with you sexually against your will? (2) Has someone forced you to look at pornographic materials against your will? (3) Has someone demanded or forced you to fondle or fondled you against your will? (4) Has someone forced you into a sexual act against your will?

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Barkley Adult ADHD rating scale–IV childhood symptoms were used by students to retrospectively self-report ADHD symptoms which occurred between the ages of 5 and 12 years.[26] It consists of 18 questions: 9 related to inattention and 9 for hyperactivity-impulsivity with each question being rated in a Likert scale. Based on the total score, it is possible to categorize the presence or absence of significant ADHD symptoms. This instrument has not been validated in India, but the scale has high internal consistency, good interobserver agreement, and high test–retest reliability.[26]

All the instruments were translated into Malayalam (the vernacular language) and back-translated to English.

Ethical considerations

Institutional Ethical Approval was received from the Government Medical College, Ernakulam, and administrative approvals were received from the school authorities before the survey. Information about the nature of the survey was provided to the parent– teacher association and parental consent was obtained. Students were informed that the survey was anonymous and would have no impact on their school work or assessments. The questionnaires were administered only to consenting students. Students were also told that if they required any help with regards to issues surveyed they could approach the School JPHNs, who had received training in handling these issues.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA Version 14.[27]

Students who responded positively to any of the 17 questions from the “harm to others from others drinking protocol” were grouped together as having suffered “any harm;” “frequently harmed” if they reported that they had been harmed 3+ times of any one harm in the last 1 year. Students reporting harm were further subcategorized to having been exposed to physical, psychological, property, and financial harm based on a positive response to any question in that domain. In each of the above groups, for the purpose of analysis, the response options were collapsed into “never” and “ever.”

Assessment of property and financial harm were based on response to a single question, and hence frequencies/proportions were calculated and no further analysis was done.

The frequencies of responses to the question of the relationship of the students to the person who has harmed them the most was calculated. Further, the responses were collapsed to two categories of “harm within the family” (if the perpetrator was within the family) and “harm outside the family” (if the perpetrator was outside the family) and analyzed.

To explore the sociodemographic, academic, and psychological factors associated with various types of harms, mixed-effect logistic regression was used. This method was used to take into account the variability across schools while finding the associated factors for various harms. To start with, in the initial analysis, multivariate models were used to find association between harms and individual variables assessed and later, multivariate models for each type of harm was assessed by adjusting for significant sociodemographic variables. The results were reported in the form of odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 6661 questionnaires which were analyzed, 3290 (49.4%) were boys with the mean age of 15.2 (range 12–19 years).

The five most common harms reported among our students were the following: being a passenger in a vehicle whose driver was drunk (males – 29.0%, females – 13.0%); being kept awake by noise of drunkenness (males – 18.8%, females – 15.5%); having family problems due to someone else drinking (males – 17.1%, females – 13.9%); having financial problems due to others’ drinking (males – 19.0%, females – 11.9%); being called names or insulted (males – 21.1%, females – 5.4%); (table with frequency responses to all questions regarding harm included in supplementary material).

The prevalence of various modalities of harm has been described in Table 1. A total of 1363 (20.6%) students reported harm in more than one domain. In all measures of harm, boys were significantly more likely to be harmed than girls (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Prevalence of harm from others drinking

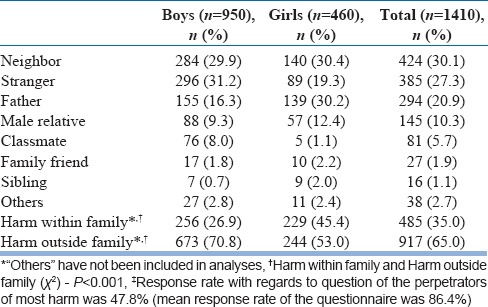

Table 2 describes the perpetrators of “most harm.” Neighbors (30.1%), strangers (27.3%), and father (20.9%) were reported as the most common perpetrators of alcohol-related harm. “Harm outside the family” was far more common than “within the family” (65% vs. 35%, P < 0.001). A significantly higher proportion of boys reported being “harmed outside the family” (70.8% vs. 53%, P < 0.001) while a significantly higher proportion of girls reported “harm within the family” (45.4% vs. 26.9%, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Perpetrators of “most harm“‡

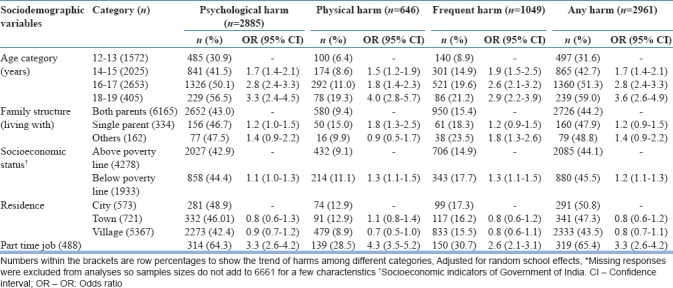

The distribution of various harms across sociodemographic variables is described in Table 3. All measures of harm increased with increasing age. Students with a part-time job and from the lower-socioeconomic status were significantly more likely to report harm. There was no significant association with regards to family structure and area of residence.

Table 3.

Correlates of harm with sociodemographic variables*

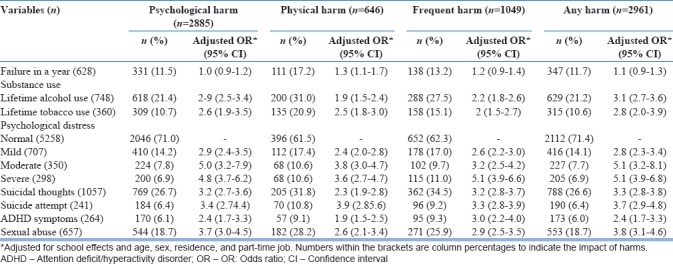

In the mixed effect multivariate logistic regression analysis, participants who reported harm in any modality were significantly more likely to have higher odds of alcohol and tobacco use, higher psychological distress, suicidality, and ADHD. Students who reported physical harm had higher odds of reporting academic failures [Table 4].

Table 4.

Psychosocial correlates of harm from alcohol

DISCUSSION

This is the largest study of harm to adolescents from others alcohol use reported from India and one of the largest in the world. The study fills a major gap in the knowledge on the prevalence of alcohol-induced harm among adolescents in India with public health implications. A significant proportion of our sample of adolescent students (44.5%) were exposed to harm from others’ alcohol use. Frequent harm was reported by 14.5% of the sample. The adolescents assessed, reported harm in multiple domains, that is, physical, psychological, property, sexual abuse, and financial problems.

A direct comparison of our prevalence rates with other studies is limited by methodological differences in the study design. Further, any participants’ experience of harm is uniquely modulated by the interaction of culture, values, attitudes, and behaviors. Despite this, rates of harm reported in our group are much higher than those reported from children and adolescents in developed countries like Australia (17%)[6] and Ireland (10%)[5] but were comparable to the finding from another Indian study where adults reported high rates of harms to children.[9] A self-reported cross-sectional study of college students from Vietnam among young adults with the mean age of 20.6 years, reported higher rates with regards to specific types of harms which were commonly assessed in both studies (“sleep disturbances (59% vs. 17.2%); property damage (22.7% vs. 2.9%); being insulted/quarreled with (49.3% vs. 13.0%); being beaten/pushed (22.7% vs. 9.7%); being in a traffic accident (22.7% vs. 2.3%).[8]

In India, inspite of a relatively low prevalence of alcohol use, culturally mediated drinking expectancies promote drinking to intoxication, and attitudes which promote alcohol-related disinhibition and violence, especially among males.[17,18] Further, the negative impact of alcohol misuse in traditionally “dry” or “ambivalent” societies is known to be greater than in traditionally “wet” cultures.[8,17,18] Alcohol use among adolescents from Kerala reported as part findings of the larger study of which the current findings are a part of is the highest reported from an adolescent Indian sample with the age of onset reported being lower than most Indian studies,[28] which could have possibly increased the risk of harm to our adolescent school students. The higher prevalence we report could be a factor of self-reporting, versus reports from parents/carers from previous studies.[3,5,6]

Females in our study reported significantly higher harm from known drinkers (45.4% vs. 26.9%, P < 0.01) while harm outside the family was significantly more among males. This replicates earlier findings that females were more likely to report problems at home and males were more to report violence in the street.[11,12,13,14] Approximately, three quarters of the perpetrators were known to the students, and harm from strangers constituted only 27.3% replicating the previous findings which have shown harm is most commonly from the “paternal figure” and the “significant other.”[2,5,6]

A major public health concern is our finding that the most common individual harm reported by our adolescents is “being in a vehicle whose driver was drunk.” Driving with an intoxicated driver is an issue of serious concern as it can contribute to injuries, accidents, disabilities, and death of innocent people. This implicates a high prevalence of drunken driving[17,19] and laxity in enforcing laws against drunken driving. The other common themes reported being kept awake by noise from public drunkenness, having family problems, being called names or insulted, being harassed or bothered in the street by intoxicated strangers have been reported from other studies studying harm from others use of alcohol, to children.[2,5,6]

Our study in addition to reporting various harms, reports certain correlates which possibly indicates vulnerability to suffering harm. Our finding that harm was higher in males increased with age is a replication of finding from previous studies.[5,8,14,29,30] The higher risk for exposure to harms among students from the lower socioeconomic status supports the previous finding that poorer socioeconomic conditions increase vulnerability to harm from others drinking.[2,5,14,31] Students with part-time jobs reported a significantly higher harms. This could be related to greater access to disposable income as well as unsupervised time away from home, both of which are known risk factors for of personal alcohol use which may consequently increase the risk of exposure to harm.[11]

Following on that observation, students reporting harm in our sample had higher rates of alcohol and tobacco use. There is a body of literature that suggests that drinkers (since they are likely to be interacting with other drinkers) are more likely than abstainers to experience harms as a result of someone else's drinking.[8,11,32]

Students reporting harm in our sample also reported greater psychological distress, suicidal thoughts, suicidal attempts, sexual abuse, and ADHD symptoms. While these associations cannot establish causality, there is growing evidence that externalizing temperaments (ADHD scores), academic failures, psychological distress, sexual and other abuse in the developmental period and suicidality, might constitute a matrix of risk, which increases vulnerability to early exposure to substance use as well as other high-risk behaviors, and also possibly increases exposure to harm from others use of alcohol in these adolescents.

The study has its limitations. All aspects were evaluated using questionnaires, and no evaluation was carried out by mental health professionals. Assessments of property and financial harm were based on response to a single question or few questions which might not have been adequate to tap these complex dimensions, and hence we made limited inferences on these dimensions. On the other hand, the strengths of the study include the assessment of a large representative sample with students self-reporting harm.

The findings from this study throw up several public health challenges: (1) a substantial proportion of adolescents in India suffer harms from others use of alcohol, (2) the harm is both from drinkers at home and intoxicated strangers in public places, and (3) the harms are strongly mediated by interacting vulnerabilities developmental stressors (adverse childhood experiences such as sexual and other abuse), externalizing temperaments (e.g., ADHD scores), psychological distress, socioeconomic disadvantage, and early substance use.

It is well accepted that societal harms from alcohol are strongly influenced by per capita consumption. These findings are a repeated assertion for improved alcohol controls in India. In practice, however, the forces which advocate alcohol control[33] are often stymied by the imperatives of revenue. In most Indian states, including Kerala, the revenue from excise taxes on alcoholic beverages is the second largest source of revenue after sales taxes, and most states are unwilling to disturb the status quo. Supply reduction is a key to reducing the negative impact of alcohol in a community. Since 2014, Kerala state has imposed restrictions in the supply of alcohol to try and tackle some of the problems due to harmful alcohol use. While it is too early to try and study whether this has had a positive public health impact, this does provide a potential platform to examine the effects of alcohol interventions on public health.[34,35] In addition to population-level controls on availability of alcohol, there needs to be a greater emphasis on individual vulnerabilities, perhaps in the form of both individual and school-based interventions to deal with psychological well-being.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was partly Funded by National Rural Health Mission (Kerala).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Junior Public Health Nurses and Block PRO's of NRHM (Ernakulam) who were involved in administering the questionnaire and Shri Ajayakumar and team who helped in the data entry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laslett AM, Mugavin J, Jiang H, Manton E, Callinan S, MacLean S, et al. The Hidden Harm: Alcohol's Impact on Children and Families. Canberra: Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callinan S. Measuring alcohol's harm to others: Quantifying a little or a lot of harm. Int J Alcohol Drug Res. 2014;3:127–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossow I. How well do survey studies capture alcohol's harm to others? Subst Abuse. 2015;9:99–106. doi: 10.4137/SART.S23503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hope A. Alcohol's Harm to Others in Ireland. Dublin: Health Service; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hope A. Hidden Realities: Children's Exposure to Risks from Parental Drinking in Ireland. Letterkenny, Ireland: North West Alcohol Forum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laslett AM, Catalano P, Chikritzhs Y, Dale C, Doran C, Ferris J, et al. The Range and Magnitude of Alcohol's Harm to Others. Fitzroy, Victoria: AER Centre for Alcohol Policy Research, Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre, Eastern Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Giles WH, et al. Growing up with parental alcohol abuse: Exposure to childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1627–40. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diep PB, Knibbe RA, Giang KB, De Vries N. Secondhand effects of alcohol use among students in Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:25848. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.25848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esser MB, Rao GN, Gururaj G, Murthy P, Jayarajan D, Sethu L, et al. Physical abuse, psychological abuse and neglect: Evidence of alcohol-related harm to children in five states of India. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35:530–8. doi: 10.1111/dar.12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manton E, MacLean S, Laslett AM, Room R. Alcohol's harm to others: Using qualitative research to complement survey findings. Int J Alcohol Drug Res. 2014;3:143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fillmore KM. The social victims of drinking. Br J Addict. 1985;80:307–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1985.tb02544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Kerr W, Bond J, Rehm J, Giesbrecht N, et al. Externalities from alcohol consumption in the 2005 US National Alcohol Survey: Implications for policy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:3205–24. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6123205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellner F. Alcohol. In: MacNeil P, Webster I, editors. Canada's Alcohol and Other Drugs Survey 1994: A Discussion of the Findings. Canada: Ministry of Public Works and Government Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laslett AM, Ferris J, Dietze P, Room R. Social demography of alcohol-related harm to children in Australia. Addiction. 2012;107:1082–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall EJ. Adolescent alcohol use: Risks and consequences. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49:160–4. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gururaj G, Girish N, Benegal V. Burden and Socio-economic Impact of Alcohol: The Bangalore study. New Delhi: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad R. Alcohol use on the rise in India. Lancet. 2009;373:17–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IAPA. Alcohol atlas of India. New Delhi, India: Indian Alcohol Policy Alliance; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. The Harm to Others from Drinking: Master Protocol. Geneva: World Health Organization/Thai Health Promotion Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Farrell M, Formigoni ML, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:494–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, King M, Kirkwood B, Nayak S, et al. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: A comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychol Med. 2008;38:221–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zolotor AJ, Runyan DK, Dunne MP, Jain D, Péturs HR, Ramirez C, et al. ISPCAN child abuse screening tool children's version (ICAST-C): Instrument development and multi-national pilot testing. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:833–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkley RA. Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV (BAARS-IV) New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaisoorya TS, Beena KV, Beena M, Ellangovan K, Jose DC, Thennarasu K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use among adolescents attending school in Kerala, India. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35:523–9. doi: 10.1111/dar.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moan IS, Storvoll EE, Sundin E, Lund IO, Bloomfield K, Hope A, et al. Experienced harm from other people's drinking: A Comparison of Northern European countries. Subst Abuse. 2015;9:45–57. doi: 10.4137/SART.S23504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esser MB, Gururaj G, Rao GN, Jernigan DH, Murthy P, Jayarajan D, et al. Harms to adults from others’ heavy drinking in five Indian states. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51:177–85. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girish N, Kavita R, Gururaj G, Benegal V. Alcohol use and implications for public health: Patterns of use in four communities. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:238–44. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossow I, Hauge R. Who pays for the drinking? Characteristics of the extent and distribution of social harms from others’ drinking. Addiction. 2004;99:1094–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Constitution of India-Park IV. Article 47, Directive Principles of State Policy; Government of India. 1950 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gururaj G, Benegal V, Girish N, Chandra V, Pandav R. Public Health Problems Caused by Harmful use of Alcohol – Gaining Less or Losing More? New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South East Asia; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful use of Alcohol. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]