Abstract

Most gallbladder cancers (GBCs) are discovered incidentally after routine cholecystectomy. The influence of timing of diagnosis on disease stage, treatment, and prognosis is not known. Patients with GBC who underwent resection at 10 institutions from 2000 to 2015 were included. Patients diagnosed incidentally (IGBC) and nonincidentally (non-IGBC) were compared. Primary outcome was overall survival (OS). Of 445 patients with GBC, 266 (60%) were IGBC and 179 (40%) were non-IGBC. Compared with IGBC, non-IGBC patients were more likely to have R2 resections (43% vs 19%; P < 0.001), advanced T-stage (T3/T4: 70% vs 40%; P < 0.001), high-grade tumors (50% vs 31%; P < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion (64% vs 45%; P = 0.01), and positive lymph nodes (60% vs 43%; P = 0.009). Receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy was similar between groups (49% vs 49%). Non-IGBC was associated with worse median OS compared with IGBC (17 vs 32 months; P < 0.001), which persisted among stage III patients (12 vs 29 months; P < 0.001), but not stages I, II, or IV. Despite accounting for other adverse pathologic factors (grade, T-stage, lymphovascular invasion, margin, lymph node), adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved OS only in stage III IGBC, but not in non-IGBC. Compared with incidental discovery, non-IGBC is associated with reduced OS, which is most evident in stage III disease. Despite being well matched for other adverse pathologic factors, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved survival only in stage III patients with incidentally discovered cancer. This underscores the importance of timing of diagnosis in GBC and suggests that these two groups may represent a distinct biology of disease, and the same treatment paradigm may not be appropriate.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a rare disease and is the sixth most common gastrointestinal malignancy in the United States.1 Overall, it is associated with a poor prognosis and an estimated 5-year survival of 5 to 13 percent.2, 3 Surgery is the only potentially curative therapy for GBC, yet 5-year survival following resection varies from 10 per cent to as high as 100 per cent, depending on tumor biology, stage of disease, and extent of resection.2, 4–6 In 50 to 70 per cent of GBC patients, the diagnosis is made incidentally on pathologic examination after routine cholecystectomy for presumed benign disease.7, 8 In fact, incidental GBC (IGBC) is found in approximately 1 in every 150 resected cholecystectomy specimens.9 Based on current management guidelines, reresection is recommended for all IGBC patients with T1b, T2, and T3 disease.10

For the remaining 30 to 50 per cent of GBC patients, the diagnosis is made nonincidentally in the preoperative setting, typically after signs and symptoms concerning for malignancy develop, such as jaundice and weight loss. In general, nonincidental GBC (non-IGBC) is thought to portend a worse prognosis than IGBC, primarily because non-IGBC patients tend to present in later stages of disease that are often less amenable to curative resection.8, 11, 12 Whether these observed survival differences are merely due to more advanced disease in non-IGBC patients or, rather, are due to distinct tumor biology is unclear. Few studies focus in detail on the clinicopathologic and survival differences between non-IGBC and IGBC, and those studies that do are often limited to single-institution series and small patient cohorts.11, 12 Furthermore, while there are data that suggest chemotherapy may improve survival in advanced GBC and in the adjuvant setting, the role of chemotherapy in the context of resected IGBC versus non-IGBC is not known.13, 14

The purpose of this large, multi-institutional study was to compare clinicopathologic factors, management strategies, and survival between patients undergoing resection for IGBC and non-IGBC.

Methods

The United States Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium is a cooperative group of 10 United States academic institutions: Emory University, Johns Hopkins University, New York University, Ohio State University, Stanford University, University of Louisville, University of Wisconsin, Vanderbilt University, Wake Forest University, and Washington University in St. Louis. All patients with GBC who underwent resection from January 2000 to March 2015 were assessed. Only patients who had information regarding timing of diagnosis (incidental or nonincidental) were included for analysis. Thirty-day mortalities were excluded from all survival analyses.

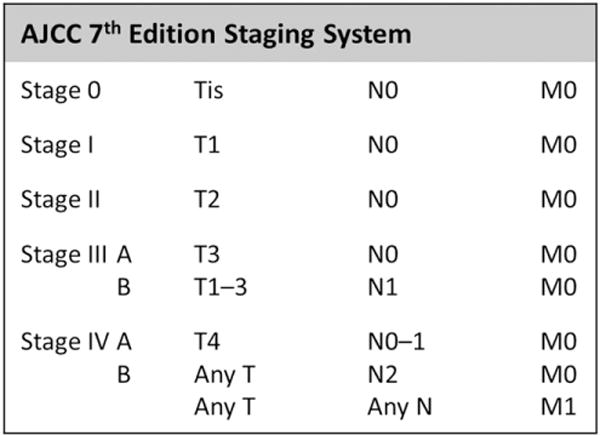

Pertinent baseline demographic, perioperative, and pathologic data were collected from a retrospective review of patient charts. Pathologic analysis was performed by experienced gastrointestinal pathologists at each institution at the time of surgery. Staging was based on American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition guidelines (Fig. 1).15 Data regarding adjuvant therapy, disease recurrence, and survival were additionally recorded. Survival information was verified when necessary using the Social Security Death Index. Each institution obtained Institutional Review Board approval before data collection.

Fig. 1.

AJCC 7th edition anatomic staging for GBC.

The primary objective was to assess the association of IGBC and non-IGBC with overall survival (OS). OS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death from any cause. The secondary objectives were to compare clinicopathologic factors between cohorts, and assess the association of adjuvant therapy with OS stratified by timing of diagnosis.

All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 23.0 software (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY). Patients with IGBC and non-IGBC were compared using χ2 analyses and Student’s t tests, where appropriate. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed to assess the association of individual pathologic factors and timing of diagnosis with OS. Log-rank analyses were performed to compare median OS between IGBC and non-IGBC cohorts, which were displayed using Kaplan-Meier survival plots. Statistical significance was predefined as two-tailed P < 0.05 for each endpoint.

Results

Of 449 patients with GBC, 445 (99%) had data regarding timing of diagnosis and were included for analysis. Then mean age of the entire cohort was 65 years and 65 per cent were female. GBC was diagnosed incidentally in 266 (60%) patients, and nonincidentally in 179 (40%).

All Patients

Comparative analyses of baseline demographics and clinicopathologic factors between IGBC and non-IGBC are shown in Table 1. Compared with IGBC, patients with non-IGBC had lower body mass indexes (26 vs 30 kg/m2; P < 0.001), and were more likely to be of nonwhite race (36% vs 21%; P < 0.001) and present with clinical jaundice (40% vs 10%; P < 0.001). Non-IGBC was also more frequently associated with finding distant disease at surgical exploration (36% vs 17%; P < 0.001), aborted procedures (43% vs 18%; P < 0.001), and major hepatectomies (19% vs 5%; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinicopathologic Variables between Patients with IGBC versus Non-IGBC

| Baseline Variables | Incidental (n = 266, 60%) | Nonincidental (n = 179, 40%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 65 ± 12 | 66 ± 11 | 0.63 |

| Male, n (%) | 99 (37) | 57 (32) | 0.29 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 30 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| White | 194 (79) | 108 (64) | |

| African-American | 27 (11) | 26 (16) | |

| Latino | 15 (6) | 9 (5) | |

| Other | 9 (4) | 25 (15) | |

| Comorbidities*, n (%) | 0.17 | ||

| 0 | 69 (30) | 58 (39) | |

| 1 | 96 (42) | 59 (40) | |

| ≥2 | 63 (28) | 32 (23) | |

| Clinical jaundice, n (%) | 24 (10) | 65 (40) | <0.001 |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy, n (%) | 80 (30) | 71 (40) | 0.05 |

| Distant disease on exploration, n (%) | 45 (17) | 63 (36) | <0.001 |

| Attempted resection, n (%) | 235 (88) | 142 (79) | 0.01 |

| Completed resection, n (%) | 217 (82) | 102 (57) | <0.001 |

| Type of resection, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Bile duct only | 9 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Cholecystectomy only | 23 (10) | 40 (30) | |

| Partial hepatectomy + portal LN | 182 (81) | 69 (51) | |

| Major hepatectomy | 11 (5) | 25 (19) | |

| EBL (mL), mean ± SD | 337 ± 346 | 389 ± 617 | 0.37 |

| Major complicationy† n (%) | 37 (16) | 33 (21) | 0.25 |

| Length of stay (days), mean ± SD | 6.9 ± 5.7 | 6.5 ± 3.0 | 0.64 |

| Final margin status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| R0 | 198 (75) | 71 (40) | |

| R1 | 16 (6) | 31 (17) | |

| R2 | 50 (19) | 77 (43) | |

| AJCC T-stage | <0.001 | ||

| Tis/T1a | 9 (4) | 5 (4) | |

| T1b | 14 (6) | 4 (3) | |

| T2 | 116 (50) | 31 (23) | |

| T3 | 80 (35) | 65 (48) | |

| T4 | 11 (5) | 30 (22) | |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Low | 24 (12) | 9 (7) | |

| Intermediate | 116 (57) | 60 (43) | |

| High | 62 (31) | 70 (50) | |

| LVI, n (%) | 53 (45) | 65 (64) | 0.01 |

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | 63 (53) | 62 (62) | 0.20 |

| Number of lymph nodes retrieved, mean ± SD | 4.8 ± 5.5 | 4.7 ± 8.0 | 0.82 |

| Any lymph node positive, n (%) | 86 (43) | 65 (60) | 0.009 |

| N1 (regional) node positive, n (%) | 82 (41) | 60 (56) | 0.02 |

| N2 (distant) node sampled, n (%) | 54 (23) | 20 (12) | 0.01 |

| N2 (distant) node positive, n (%) | 14 (19) | 8 (29) | 0.41 |

| AJCC anatomic stage, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Stage 0 | 7 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Stage I | 12 (6) | 6 (4) | |

| Stage II | 51 (23) | 11 (7) | |

| Stage IIIA | 28 (13) | 16 (11) | |

| Stage IIIB | 59 (27) | 30 (20) | |

| Stage IVA | 9 (4) | 18 (12) | |

| Stage IVB | 53 (24) | 68 (45) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | 8 (3) | 8 (5) | 0.54 |

| Chemotherapy | 8 (3) | 8 (5) | 0.58 |

| Radiation | 1 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.34 |

| Adjuvant therapy, n (%) | 103 (52) | 69 (54) | 0.85 |

| Chemotherapy | 99 (49) | 65 (49) | 1.00 |

| Radiation | 48 (25) | 23 (19) | 0.26 |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 60 (35) | 38 (50) | 0.04 |

| Locoregional only | 11 (18) | 5 (14) | 0.43 |

| Distant | 49 (82) | 30 (86) |

BMI, body mass index; LN, lymph node; EBL, estimated blood loss.

Includes hypertension, prior cardiac event, congestive heart failure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease.

Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa.

On pathology, non-IGBC was associated with a higher incidence of R1 (17% vs 6%) and R2 (43% vs 19%; P < 0.001) resections, advanced AJCC T-stage (T3/T4: 70% vs 40%; P < 0.001), poor tumor differentiation (50% vs 31%; P = 0.001), and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (64% vs 45%; P = 0.01). Despite similar lymph node yields between groups, non-IGBC patients more frequently had lymph-node-positive disease compared with IGBC patients (60% vs 43%; P = 0.009). AJCC stage IV disease was also more common in non-IGBC than in IGBC (57% vs 28%; P < 0.001).

There was no difference between non-IGBC and IGBC in the receipt of neoadjuvant therapy (5% vs 3%; P = 0.54) or adjuvant therapy (54% vs 52%; P = 0.85). Of those patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy (total n = 164), 67 per cent were treated with a gemcitabine-based regimen, and no difference was seen between groups. Disease recurrence was more common in non-IGBC than IGBC (50% vs 35%; P = 0.04), but there was no difference in the region of recurrence, with distant disease recurrence being the most common in both groups (86% vs 82%; P = 0.43).

Survival Analysis

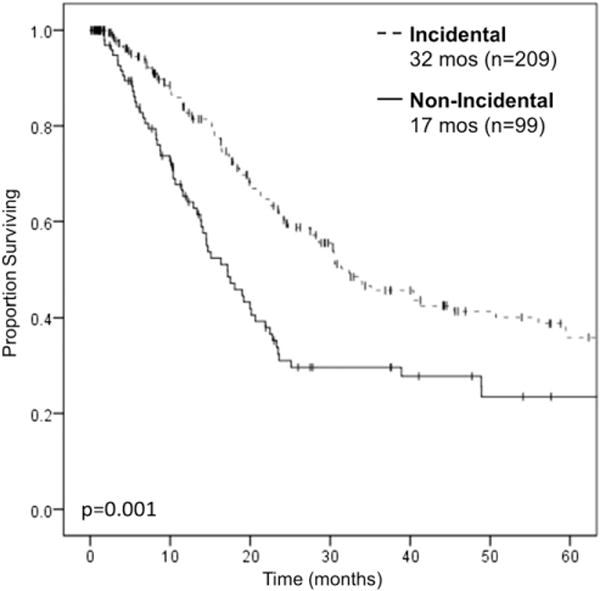

Median follow-up for survivors was 12.3 months (interquartile range: 2.5–37.5). Median OS among all patients was 18.7 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 16.3–21.1]. Median OS among only patients who underwent curative-intent resections was 24.3 months (95% CI: 19.4–29.2). Non-IGBC was associated with worse median OS (17.2 months; 95% CI: 13.0–21.3) compared with IGBC (32.4 months; 95% CI, 23.3–41.4; P = 0.001; Fig. 2). Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for OS are shown in Table 2. Non-IGBC persisted as a poor prognostic factor [hazard ratio (HR): 2.18; 95% CI, 1.16–4.09; P = 0.015) on multivariable analysis, as did T3 and T4 diseases, and LVI, but not margins status, tumor grade, lymph node status, or perineural invasion.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for OS in patients with IGBC versus non-IGBC. Patients with non-IGBC had worse median OS (17 months) compared with patients with IGBC (32 months). Log-rank P = 0.001. Excludes 30-day mortalities and R2 resections.

Table 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis for OS among All Curative-Intent Resections*

| Univariable Cox Regression

|

Multivariable Cox Regression

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Nonincidental versus incidental | 1.74 (1.26–2.40) | 0.001 | 2.18 (1.16–4.09) | 0.02 |

| Margin positive | 3.58 (2.45–5.22) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.71–1.47) | 0.36 |

| Grade | ||||

| Low | Reference | 0.06 | Reference | 0.64 |

| Intermediate | 1.97 (0.98–3.94) | 0.002 | 0.75 (0.22–2.55) | 0.89 |

| High | 2.98 (1.47–6.04) | 0.92 (0.28–3.04) | ||

| AJCC T-stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | 0.12 | Reference | 0.11 |

| T2 | 1.90 (0.85–4.20) | <0.001 | 3.83 (0.74–19.87) | 0.004 |

| T3 | 5.39 (2.48–11.74) | <0.001 | 11.07 (2.15–56.86) | 0.01 |

| T4 | 8.22 (3.35–20.21) | 10.49 (1.71–64.46) | ||

| Lymph node positive | 1.93 (1.37–2.72) | <0.001 | 1.42 (0.77–2.59) | 0.26 |

| LVI | 2.33 (1.53–3.54) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.03–3.68) | 0.04 |

| Perineural invasion | 2.34 (1.51–3.63) | <0.001 | 1.50 (0.79–2.84) | 0.22 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.92 (0.63–1.35) | 0.68 | — | — |

Excludes aborted/R2 resections.

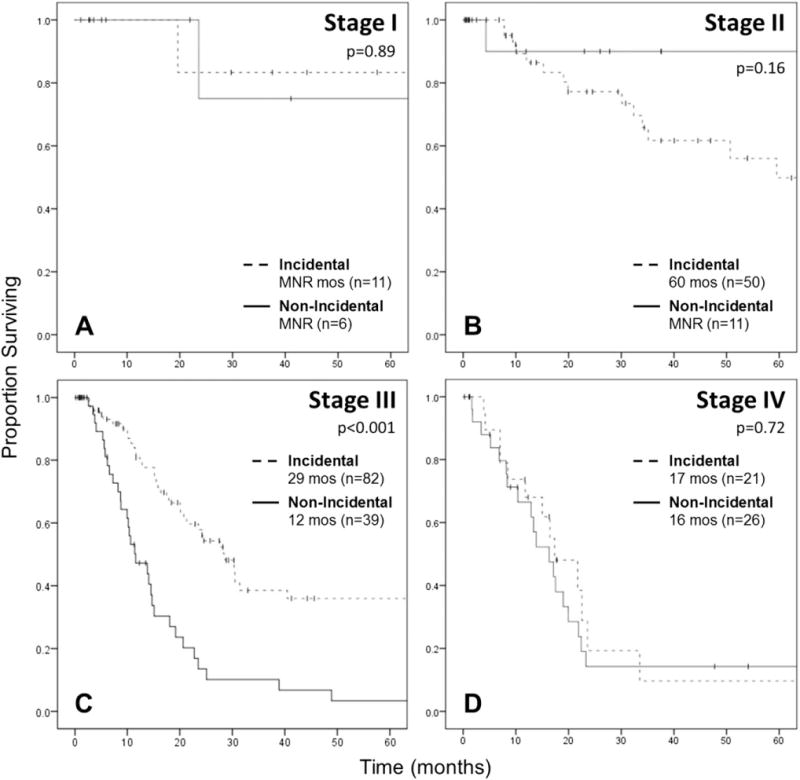

Stage-Specific Analysis

On stratum-specific analysis by AJCC stage, non-IGBC was associated with worse median OS only among patients with stage III disease (11.6 vs 28.6 months; P < 0.001), but not stages I, II, or IV (Fig. 3A–D). Comparing clinicopathologic variables between non-IGBC to IGBC among stage III only, non-IGBC patients were more likely to have R1 resections (36% vs 9%; P = 0.001), but there was no difference in the distribution of tumor grade, T-stage, lymph node status, LVI, perineural invasion, or receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy between groups. On univariable Cox regression analysis, non-IGBC, positive margin, and T3 disease were associated with worse OS, whereas adjuvant therapy was associated with improved survival. Only non-IGBC (HR: 2.34; 95% CI: 1.33–4.13; P = 0.003) and adjuvant therapy persisted on multivariable analysis (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for OS in patients with IGBC versus non-IGBCs, stratified by stage. (A) Stage I, log-rank P = 0.89. (B) Stage II, log-rank P = 0.16. (C) Stage III, log-rank P < 0.001. (D) Stage IV, log-rank P = 0.72. Excludes 30-day mortalities and R2 resections.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis for OS among Only Stage III Curative-Intent Resections*

| Univariable Cox Regression

|

Multivariable Cox Regression

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Nonincidental versus incidental | 3.01 (1.87–4.84) | <0.001 | 2.26 (1.21–4.23) | 0.01 |

| Margin positive | 2.77 (1.62–4.71) | <0.001 | 1.78 (0.84–3.76) | 0.13 |

| Grade | ||||

| Low | Reference | 0.74 | — | |

| Intermediate | 0.84 (0.30–2.38) | 0.97 | — | — |

| High | 0.98 (0.34–2.81) | — | ||

| AJCC T-stage | ||||

| T1† | — | — | ||

| T2 | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| T3 | 1.97 (1.13–3.45) | 0.02 | 1.52 (0.75–3.08) | 0.25 |

| Lymph node positive | 1.01 (0.62–1.63) | 0.98 | — | — |

| LVI | 1.37 (0.71–2.65) | 0.35 | — | — |

| Perineural invasion | 1.49 (0.75–2.98) | 0.25 | — | — |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.45 (0.26–0.77) | 0.004 | 0.48 (0.27–0.84) | 0.01 |

Excludes AJCC stages I, II, and IV, and aborted/R2 resections.

Insufficient number of patients for analysis.

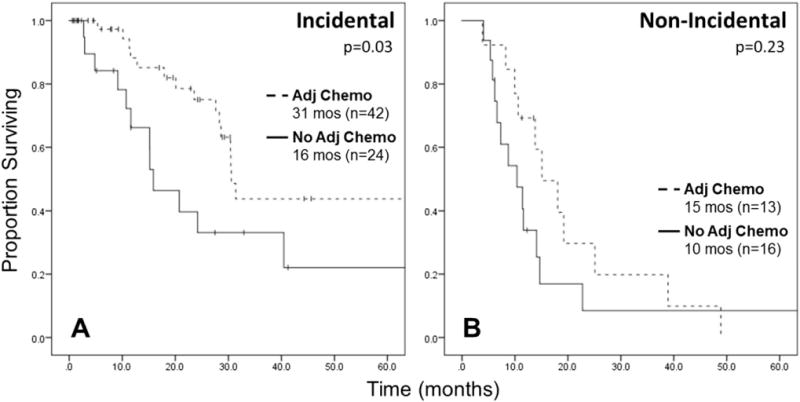

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved median OS only among patients with stage III disease (30.4 vs 14.1 months; P = 0.003), but not stages I, II, or IV, or among the whole cohort of patients who underwent curative-intent resections. When stratified by timing of diagnosis among only stage III patients, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved median OS for IGBC (30.5 vs 15.9 months; P = 0.03; Fig. 4A), but not for non-IGBC (15.1 vs 10.4 months; P = 0.23; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for OS in stage III patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy versus no adjuvant chemotherapy, stratified by timing of diagnosis. (A) IGBC, log-rank P = 0.03. (B) Non-IGBC, log-rank P = 0.23. Excludes 30-day mortalities and R2 resections.

Discussion

GBC is a rare disease with an overall poor prognosis. Because of its rarity, studies examining important clinicopathologic factors and management strategies for GBC are often limited to single-institution series and small patient cohorts. In this study, we used a large, multi-institutional database to investigate the importance of timing of diagnosis (incidental versus nonincidental) in relation to other prognostic factors on OS. We found that, overall, non-IGBC was associated with more advanced disease than IGBC, yet even accounting for other poor prognostic factors, it was still independently associated with worse OS. On stage-specific analysis, non-IGBC was associated with worse OS only among stage III patients, but not stages I, II, and IV. Although not associated with survival among all patients, adjuvant therapy was also associated with improved OS among only stage III patients. On further analysis, we found that adjuvant therapy was associated with improved OS only among stage III IGBC patients, but not stage III non-IGBC patients.

In general, non-IGBC carries a worse prognosis than IGBC, as patients tend to be diagnosed in later stages of disease after more ominous symptomatology has developed.8, 11, 12 In a study by Shih et al., patients with non-IGBC were more likely to present with jaundice, weight loss, and stages III and IV disease, and less likely to undergo R0 resections than those with IGBC.11 As expected, non-IGBC was associated with worse median OS (8 months) compared with IGBC (21 months). This survival difference persisted on subset analyses of only patients who underwent curative-intent resections and those with stage II disease, as well as on a multivariable analysis of patients who underwent at least a partial hepatectomy. However, this study included a total of only 107 patients, only 67 of whom underwent resection, and no consideration was given to the role of chemotherapy. Furthermore, few other modern studies explore in detail the clinicopathologic and potential biologic factors that may influence the observed survival difference between IGBC and non-IGBC, and most are similarly limited by low numbers of patients. Pawlik et al. demonstrated a significant survival difference between non-IGBC and IGBC, but focused primarily on patients in the latter cohort, and not on the differences between the two.8 In a single-institution series by Cziupka et al., the median OS for non-IGBC was 6.7 months compared with 22.3 months for IGBC. Yet this study only included a total of 42 patients, and timing of diagnosis was not examined beyond the context of metastatic disease and R2 resections.12

In the current study of 445 patients, 266 had IGBC and 179 had non-IGBC. Similar to Shih et al., we found that non-IGBC was associated with indicators of more advanced disease and known poor prognostic factors: clinical jaundice, distant disease on exploration, aborted procedures, major hepatectomy, positive margins, advanced T-stage and disease stage, high-tumor grade, LVI, and positive lymph nodes. After excluding aborted procedures and noncurative-intent resections, non-IGBC was still associated with worse OS than IGBC, which persisted on multivariable analysis accounting for all other significant pathologic factors. Unlike Shih et al., however, our study demonstrated a survival difference only among stage III patients, and not stages I, II, or IV. In fact, among the stage III cohort, only timing of diagnosis (non-IGBC versus IGBC) and adjuvant therapy were associated with survival on both univariable and multivariable analyses, whereas margin status, tumor grade, T-stage, lymph node status, LVI, or perineural invasion were not.

Adjuvant therapy after resection has increasingly become a topic of interest for GBC patients, yet results from various studies have been mixed.16–20 A recent meta-analysis of 10 retrospective studies evaluating adjuvant therapy compared with surgery alone for resected GBC demonstrated that, although there was no improvement in survival for the entire cohort, adjuvant therapy was associated with improved survival among patients with R1 resections, lymph-node-positive disease, and combined stages II and III.14 However, the studies included a mixture of single- and multimodality therapies, and subset analyses for margin and nodal status were based on results from only 1 to 2 studies. Furthermore, all of the studies that showed a positive association between adjuvant therapy and survival were from Asian countries, which may limit the applicability of their results to Western populations, and none of them evaluated adjuvant therapy in the context of timing of diagnosis.

In the current study, adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without radiation, was administered to approximately half of patients, and two-thirds of those were treated with gemcitabine-based regimens. Adjuvant chemotherapy was only associated with improved OS among stage III patients, but not among all patients who underwent curative-intent resections, or those with stages I, II, or IV disease. When further stratified, adjuvant therapy was specifically only associated with improved OS in stage III IGBC, and not stage III non-IGBC, despite the cohorts being relatively well matched. As previously mentioned, among the stage III cohort, both timing of diagnosis and adjuvant chemotherapy were the only factors associated with survival on multivariable analysis, even after accounting for other known adverse pathologic factors, such as margin status and T-stage.

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective nature makes disease recurrence and survival data challenging to capture, and introduces a selection bias that makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from our results. However, this is one of the largest studies that compares IGBC and non-IGBC, and includes data from 10 geographically diverse, academic institutions, which eliminates single-institution bias, and more closely represents the general practice patterns and disease characteristics of the United States. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the largest and only study that examines the role of adjuvant therapy in the context of timing of diagnosis. Although pathologic analysis was not standardized across institutions, all involved academic centers have experienced gastrointestinal pathologist who performed the pathologic review.

Conclusions

In conclusion, compared with incidental discovery, non-IGBC is associated with reduced OS, which is evident specifically in stage III disease. Despite being well matched and accounting for other adverse pathologic factors, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved survival only in stage III patients with IGBC, and not in those with non-IGBC. This underscores the importance of timing of diagnosis in GBC and suggests that these two groups may represent distinct tumor biologies that require unique treatment paradigms. Further tissue-based studies should be performed to investigate the potential differences in pathophysiology and tumorigenesis between IGBC and non-IGBC, and current ongoing and future adjuvant therapy trials should consider the potential influence of timing of diagnosis in their analyses and trial design.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000454. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented at the Southeastern Surgical Congress, February 26, 2017, Nashville, TN.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cubertafond P, Gainant A, Cucchiaro G. Surgical treatment of 724 carcinomas of the gallbladder. Results of the French Surgical Association Survey. Ann Surg. 1994;219:275–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199403000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson DS. Carcinoma of the gall-bladder: an experience and review of the literature. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995;65:724–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benoist S, Panis Y, Fagniez PL. Long-term results after curative resection for carcinoma of the gallbladder. French University Association for Surgical Research. Am J Surg. 1998;175:118–22. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lendoire JC, Gil L, Duek F, et al. Relevance of residual disease after liver resection for incidental gallbladder cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:548–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ethun CG, Postlewait LM, Le N, et al. A novel pathology-based preoperative risk score to predict locoregional residual and distant disease and survival for incidental gallbladder cancer: a 10-institution study from the U.S. extrahepatic biliary malignancy consortium. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;24:1343–50. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5637-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuks D, Regimbeau JM, Le Treut YP, et al. Incidental gallbladder cancer by the AFC-GBC-2009 Study Group. World J Surg. 2011;35:1887–97. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Vigano L, et al. Incidence of finding residual disease for incidental gallbladder carcinoma: implications for re-resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1478–86. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0309-6. discussion 1486–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi KS, Choi SB, Park P, et al. Clinical characteristics of incidental or unsuspected gallbladder cancers diagnosed during or after cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1315–23. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aloia TA, Jarufe N, Javle M, et al. Gallbladder cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:681–90. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih SP, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, et al. Gallbladder cancer: the role of laparoscopy and radical resection. Ann Surg. 2007;245:893–901. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31806beec2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cziupka K, Partecke LI, Mirow L, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in gallbladder cancer: a single-centre experience. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:899–907. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-0950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma N, Cheng H, Qin B, et al. Adjuvant therapy in the treatment of gallbladder cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:615. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1617-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. Gallbladder AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 211–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todoroki T, Kawamoto T, Otsuka M, et al. Benefits of combining radiotherapy with aggressive resection for stage IV gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindell G, Holmin T, Ewers SB, et al. Extended operation with or without intraoperative (IORT) and external (EBRT) radiotherapy for gallbladder carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, et al. Prognostic factors of patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma following aggressive surgical resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1007–16. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HY, Kim YH, Jung GJ, et al. Prognostic factors for gallbladder cancer in the laparoscopy era. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;83:227–36. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2012.83.4.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balachandran P, Agarwal S, Krishnani N, et al. Predictors of long-term survival in patients with gallbladder cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]