Abstract

Background

Anxiety sensitivity (AS) reflects an individual’s belief that experiencing anxiety will cause illness or embarrassment (Reiss & McNally, 1985), and may be a reason individuals self-medicate with alcohol (Hersh & Hussong, 2009). Harsh or indulgent parenting could contribute to the development of AS. We examined the direct and indirect associations between parenting styles and alcohol-related variables through AS and impaired control over drinking (IC; i.e., perceived failure to adhere to limits on alcohol consumption in the future; Heather et al., 1993).

Methods

A multiple-group structural equation model with 614 university students (344 men; 270 women) was examined. Structural invariance tests were conducted to evaluate moderation by gender. We used a bias corrected bootstrap technique to obtain the mediated effects.

Results

Father authoritarianism and mother permissiveness were directly linked to AS among women, whereas father permissiveness was directly linked to AS among men. This suggests unique parental influences based on gender regarding AS. While AS was directly linked to alcohol-related problems for both men and women, several gender-specific associations were found. AS was directly linked to IC for men but not for women. For men, father permissiveness was directly related to AS, and AS mediated the indirect link between father permissiveness and IC along both the heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related problems pathways. Similar to other internalizing constructs (e.g., neuroticism and depression), higher AS was directly associated with less heavy episodic drinking but more alcohol-related problems.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the dangers of AS for men as an important correlate of under-controlled drinking behaviors. Additionally, permissive parenting of the same-gender parent was associated with AS, which is consistent with the gender-matching hypothesis. Together, these results underscore the importance of measuring the independent influence of both parents (see Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; van der Vorst et al., 2006).

Keywords: Anxiety Sensitivity, Impaired Control over Drinking, Parenting Styles, Alcohol Use, Alcohol-Related Problems

1. Introduction

Anxiety sensitivity (AS) is an individual’s belief that experiencing anxiety will lead to harmful psychological, physical, and social consequences, and like other temperament variables, is theoretically presumed to develop from both heritable and environmental factors (Eisenberg et al., 2010; Reiss & McNally, 1985). AS is the general tendency to respond fearfully to one’s own anxiety symptoms and has been distinguished from the direct experience of anxiety alone (Reiss et al., 1986). It is also a unique risk factor for the development of various disorders, such as anxiety (Allan et al., 2014; Timpano et al., 2015), panic (Hayward et al., 2000), depression (Cox et al., 2001; Timpano et al., 2015), and even suicide (Capron et al., 2012). Moreover, a heightened “fear of fear” encourages avoidance behaviors (Reiss, 1991), which may increase the potential for AS to function as a risk factor for alcohol use disorders (Schmidt et al., 2007). For example, negative expectations surrounding the experience of anxiety may motivate individuals with elevated AS to use alcohol to suppress and avoid feared anxiety reactions (Schmidt et al., 2007). Past studies focusing on alcohol-related outcomes have found that people with increased levels of AS consumed higher amounts of alcohol (DeMartini & Carey, 2011) and had more problem-drinking behaviors (Conrod et al., 1998).

Taylor and colleagues (2008) suggest that a large portion of variance regarding AS is explained by environmental factors such as relationships with one’s parents. This is consistent with Social Learning Theory (Bandura & Walters, 1963), which suggests that offspring learn to model the stereotypic behaviors of their same-sex parental figures, such as responses to distress and drinking. Extant research has suggested that parent and offspring gender matches (Doumas et al., 2015; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; van der Vorst et al., 2006) and mismatches (Luk et al., 2010) should be further explored in the literature as the combinations explain unique variance across a variety of constructs, such as self-regulation (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001) and impulsivity (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; Patock-Peckham et al., 2011), in relation to alcohol use and related problems. Moreover, constructs such as parental monitoring and parental communication seem to reflect unique influences on alcohol and other substance use and related problems, depending on the gender of the offspring (e.g., Doumas et al., 2015; Luk et al., 2010). Specifically, parental monitoring was associated with lower levels of heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related consequences for females, whereas parental disapproval of teen drinking was associated with lower levels of heavy episodic drinking for males (Doumas et al., 2015). Regarding parental communication, healthy, easy parent-adolescent communication is negatively associated with substance use among males but has no such relationship among females (Luk et al., 2010). Thus, the links between parental influences and offspring outcomes are likely to be complex.

Presumably, modeling the same-sex parent perpetuates embedded and enduring gender stereotypes that reinforce what society deems as being acceptable and unacceptable behaviors for men and women (McLean & Anderson, 2009). Even though women typically experience more AS symptoms than men (Stewart et al., 1997), men experiencing AS symptoms may find it more difficult to openly express them. For instance, men are discouraged from showing any visible signs of anxiety-related symptoms and, as a result, are more reluctant to express emotions or behave in a way that may jeopardize their independence compared to women (McLean & Anderson, 2009). Men who emotionally self-disclose are perceived to be more passive and unstable, and consequently, less likable (Moss-Racusin et al., 2010). While it remains socially acceptable for women to appear anxious, timid men who violate masculine stereotypes face social and psychological consequences (e.g., lowered self-esteem and impaired well-being; Witt & Wood, 2010). These studies suggest that the expression of anxiety is highly inconsistent with the male gender role. While recent research suggests that a gender gap in drinking patterns is narrowing (Keyes et al., 2011), men across a wide variety of settings and cultures still typically drink more often and in greater quantities than women (Hunt et al., 2015). Accordingly, men with higher AS may rely on drinking to escape from their feelings and cope with anxiety-related symptoms (Kerr-Corrêa et al., 2007).

The degree to which AS leads to negative drinking outcomes may also be driven by self-medication motivations to drink and expectancies surrounding the anxiolytic benefits of alcohol (DeMartini & Carey, 2011). According to the Self-Medication Theory (Hersh & Hussong, 2009), alcohol is often used as a coping mechanism when experiencing elevated states of discomfort related to anxiety. Cooper (1994) found that drinking to cope was one of the main motivating factors for consuming alcohol and was a primary contributor to the development and maintenance of drinking problems (Kushner et al., 2001). Overall, individuals with high AS experience greater arousal-dampening effects of alcohol (MacDonald et al., 2000), leading to negative reinforcement by using alcohol to treat anxiety (Stewart et al., 2001). More specifically, as appearing anxious is less acceptable for men in society, we expected a stronger association between AS and negative drinking outcomes among men than among women. Moreover, self-reported AS has been found to be related to childhood exposure to parental lack of control over both anger and alcohol use (Watt & Stewart, 2003). Individuals subjected to rejecting, threatening, and hostile behaviors by parents during childhood may be more likely to develop AS (Scher & Stein, 2003). Understanding the etiology of AS is important as cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) have been found to be efficacious in reducing drinking problems among high AS populations (Watt et al., 2006).

AS may disrupt one’s regulatory abilities (Tull et al., 2009) and, in turn, lead to increased drinking and alcohol-related problems through impaired control over drinking. Impaired control over drinking (IC) is characterized by a failure to properly manage or regulate alcohol use despite self-imposed intentions to regulate one’s own drinking behavior (Heather et al., 1993, p. 701; Leeman et al., 2012). IC has been associated with problem drinking both cross-sectionally (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001; Patock-Peckham et al., 2011) and prospectively (Leeman et al., 2009). IC is conceptualized as a core risk factor of poor alcohol-related outcomes (Heather et al., 1993), particularly among young adults (Leeman et al., 2009; Leeman et al., 2012). Prospectively, AS coupled with being male has been found to have a unique influence on the development of alcohol use disorders (Schmidt et al., 2007). Based on a review of the extant literature, it is conceivable that AS may lead to the development and maintenance of a maladaptive cycle of uncontrolled drinking behaviors and alcohol use (Sher et al., 2005). Thus, we seek to specifically determine whether IC will mediate the link between AS and alcohol-related problems.

AS is the inability to regulate anxiety-related symptoms once becoming aware of a physiological response. As previously mentioned, Tull and colleagues (2009) found that AS is associated with emotion regulation difficulties. Similarly, Wardell and colleagues (2015) found that IC is related to emotional impulsivity when feeling bad (i.e., negative urgency) as well as emotional impulsivity when feeling good (i.e., positive urgency). It has been suggested that IC is a manifestation of impulsivity specifically directed towards alcohol use (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006). Thus, we hypothesized that AS may be directly related to IC.

Enhanced fearfulness to anxiety-related sensations may be shaped by several factors (Reiss et al., 1986), including parental modeling and parenting practices (Albano et al., 2003). Regarding parental modeling, paternal AS has been associated with offspring AS, as well as anxiety and mood psychopathology (East et al., 2007). In addition, Timpano and colleagues (2015) found that parenting styles were differentially associated with AS, controlling for depression and anxiety symptoms, in a nonclinical sample of emerging adults. Specifically, they found that AS mediated the relationship between specific parenting styles and anxiety symptoms and depression. In particular, perceived parenting styles during childhood have been associated with individual differences in AS (Watt et al., 1998), although no prior study has examined whether parenting styles have an indirect influence on IC through the mediating mechanism of AS, thereby increasing the risk of negative drinking outcomes.

In the current study, we examined associations between AS and Baumrind’s three parenting styles (1971, p. 22): (a) permissive (i.e., passive parenting with little to no regulation); (b) authoritarian (i.e., harsh parenting coupled with a lack of warmth); and (c) authoritative (i.e., engaged parenting incorporating a balance of rules/reasoning and warmth/emotional support). In general, authoritative parenting has been linked to positive developmental outcomes (Steinberg, 2001). Specifically, children raised in authoritative environments experience fewer anxiety-related symptoms (Davis et al., 2015; McLeod et al., 2007) and have an increased ability to self-regulate (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; Zeinali et al., 2011). In contrast, authoritarian and permissive parenting styles have been associated with elevated AS (Timpano et al., 2015). Presumably, AS may be related to permissive and authoritarian parenting styles, which have been associated with internalizing symptoms among offspring. For instance, permissive parenting of gender-matched offspring is positively associated with poor self-regulatory abilities for both men and women (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001). Further, father authoritarianism is directly linked with more neurotic symptoms (e.g., worry) among men (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2009). In addition, negative bonds with authoritarian fathers have been directly associated with depression among both women and men, although this relationship was stronger among women than men (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007; 2009b).

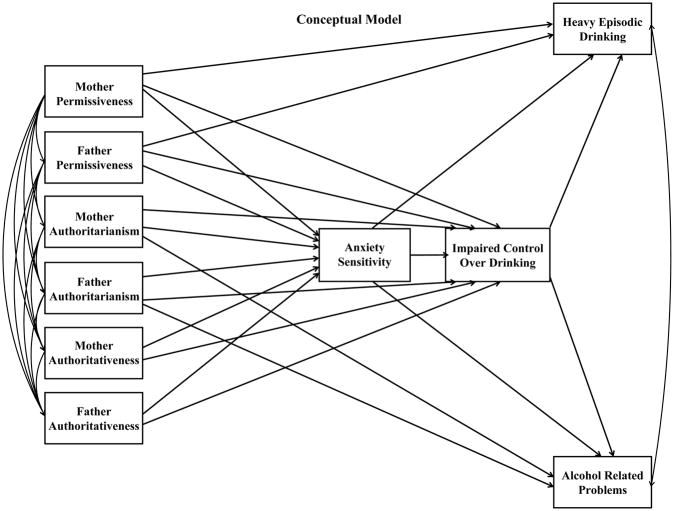

Conceivably, permissive and authoritarian parenting styles may heighten children’s propensity for developing a belief that anxiety symptoms are harmful by lowering their capacity to appropriately manage emotions (van der Sluis et al., 2015). Further, parenting practices characterized by either too little or too much structure may condition children to develop skewed perceptions of control and inadvertently enhance their feelings of anxiety (Barlow, 2002). Thus, we anticipated that permissive and authoritarian parenting styles would be positively associated with AS, whereas a more balanced, authoritative approach would be protective in nature for both men and women. In particular, we reasonably hypothesized that permissive parenting would have stronger influences on gender-matched offspring (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006), whereas authoritarian parenting of either gender (Scher & Stein, 2003) would be associated with more AS symptoms among offspring. Our study was the first to examine parenting styles from both mothers and fathers simultaneously in relation to AS on the alcohol-related problems pathway. Furthermore, we also examined AS as a possible mediator linking parenting styles to IC and alcohol-related behaviors (e.g., heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related problems) and tested whether these relationships were moderated by gender. We hypothesized that permissive parenting of gender-matched offspring and authoritarian parenting, in general, would be associated with higher AS, whereas, authoritative parenting would be associated with less AS for both men and women. Furthermore, we hypothesized that higher levels of AS would be associated with more IC, which in turn would be related to heavier alcohol use and more alcohol-related problems for both men and women, but more so for men. Figure 1 depicts a conceptual model of all examined paths among the exogenous and endogenous variables in the model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of all examined paths among the exogenous and endogenous variables in the model.

Conceptual Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 835 participants completed the survey for an introductory psychology research credit or for extra credit. Of those, 614 participants (344 men; 270 women) disclosed that they were currently a drinker of alcoholic beverages. As we were mostly interested in analyzing problematic alcohol use among those who engaged in drinking behaviors, we only examined the 614 participants who stated that they used alcohol. Of the participants that were current drinkers, 55.9% were men, and the mean age of the participants was 20.42 years (SD = 3.27). Of the participants, 410 were Caucasian, 87 were Hispanic, 63 were Asian, 25 were African-American, 7 were Native American, and 22 Other.

2.2. Procedures

All data were collected in person with individuals filling out multiple questionnaires in one session. To ensure participant anonymity, a physical drop box was used to collect surveys.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Anxiety Sensitivity Index

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI) (Reiss et al., 1986) is a 16-item assessment with good psychometric properties. The ASI measures an individual’s concerns about negative consequences associated with anxiety-related symptoms (e.g., “It scares me when my heart beats rapidly” and “It is important to me to not appear nervous”). Participants rated each item by selecting one of five phrases ranging from 0 (very little) to 4 (very much). An individual’s Anxiety Sensitivity score is the sum of the scores on the 16 items with higher scores indicating higher sensitivity to anxiety symptoms. The α reliability was .92 for this sample.

2.3.2. Impaired Control (IC)

We utilized part 3 of the Impaired Control Scale (Heather et al., 1993, p. 704). Higher scores on this 10-item measure indicate perceived beliefs regarding difficulty in exerting control over future drinking (i.e., an inability to stop drinking at will). A sample item included, “Even if I intended having only one or two drinks, I would end up having many more.” Responses for the Impaired Control Scale were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither agree nor disagree), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). The α reliability was .84 for this sample.

2.3.3. Parental Authority Questionnaire

The Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ; Buri, 1991) is a 60-item measure, 30 per parent, based on Baumrind’s (1971) prototypes of permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative parenting styles. The 10-item permissiveness subscale included items like, “Most of the time as I was growing up my (mother/father) did what the children in the family wanted when making family decisions.” The 10-item authoritarianism subscale included items like, “My (mother/father) felt that wise parents should teach their children early just who is boss in the family.” The 10-item authoritativeness subscale included items like, “As the children in my family were growing up, my (mother/father) consistently gave us direction and guidance in rational and objective ways.” Responses for the PAQ were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (unsure), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). The α reliabilities in this sample were as follows: mother permissive .79, father permissive .81, mother authoritarian .85, father authoritarian .88, mother authoritative .86, and father authoritative .87.

2.3.4. Heavy Episodic Drinking

Heavy Episodic Drinking (Wood & Rhodes, 1992) was measured with the single-item, “How many times in the past year (when you were drinking) did you drink 5 or more (“4” for women) bottles or cans of beer, glasses of wine, or drinks of distilled spirits on a single occasion?” Response options range from 0 (never), 1 (less than once a month), 2 (once a month), 3 (2 or 3 times a month), 4 (once a week), 5 (2 or 3 times a week), 6 (4 or 5 times a week), and 7 (daily or nearly daily).

2.3.5. Alcohol-Related Problems

We utilized the mean score from the 27-item Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992). Response options for each item range from 0 (no, never), 1 (yes, but not in the past year), 2 (once in the past year), 3 (2 times in the past year), 4 (3 times in the past year), 5 (4 to 6 times in the past year), 6 (7 to 11 times in the past year), 7 (12 to 20 times in the past year), 8 (21–39 times in the past year), and 9 (40 or more times in the past year). Sample items included, “Have you driven a car when you knew you had too much to drink to drive safely?” and “Have you ever gotten into trouble at work or school because of drinking?” The α reliability was .90 for this sample.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained using SPSS, and the multiple group path analyses were conducted within a structural equation modeling framework in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). To formally test gender differences, we conducted an overall structural invariance test by simultaneously constraining all path coefficients to be equal across gender groups. Because the chi-square statistic exceeded the critical value (p < .05), we conducted subsequent path analyses separately by men and women and conducted single df invariance tests for each path in the model to determine if pathway strength was the same or different among the two genders. Next, two- and three-path mediational effects were examined. Model fit was evaluated with chi-square statistics, RMSEA (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler 1998), and CFI (Bentler, 1990). Indirect effects were tested by examining whether the parametric bootstrapped (K = 20,000) 95% asymmetric confidence interval around the estimates of the indirect effects included zero (MacKinnon, 2008; Taylor et al., 2008).

3. Results

Table 1 depicts the descriptive statistics for all variables examined within the path models. The theoretical model depicted in Figure 1 was examined as a multiple group model based on gender and provided good fit to the data, χ2 (16df) = 10.314, p = 0.8497; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = .012; RMSEA = 0.000; 90% [0.000, 0.030]. The overall invariance test yielded a χ2 (21df) = 45.759, p < .01, thereby exceeding the χ2 difference value for 21df, suggesting men and women should be examined in separate models. Figures 2 and 3 depict the fit path models for men and women, respectively. Standardized coefficients are shown in Figure 2 for men and Figure 3 for women with all exogenous variables allowed to correlate freely in the model. Table 2 depicts the one degree of freedom structural invariance tests that allow an investigator to determine if the paths for men and for women are significantly different from each other. As shown in Table 2, the pathway from AS to IC is stronger for men (unstandardized β = .265; S.E. = .044, Z = 5.985, p < .001) than for women (unstandardized β = .092; S.E. = .055, Z = 1.692, p = .091). Thus, IC mediated the indirect link from AS to alcohol-related problems for men [indirect effect = .118, S.E. = .029, Z = 4.056, p < .001; 95% CI (.076, .171)] but not for women [indirect effect = .033, S.E. = .023, Z = 1.466, p = .143; 95% CI (−.002, .073); zero is in the interval]. In addition, the negative pathway from AS to heavy episodic drinking was stronger for men (unstandardized β = −.352; S.E. = .124, Z = −2.850, p = .004) than for women (unstandardized β = .072; S.E. =.115, Z =0.624, p =.533). Furthermore, the pathway from father authoritarianism to alcohol-related problems was stronger for men (unstandardized β = .007; S.E. = .004, Z = 1.741, p = .082) than for women (unstandardized β = .004; S.E. = .003, Z = 1.206, p = .228).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables; (344 men = bottom in italics, 270 women = top in bold).

Mean, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables based on a sample of 344 men (values on the lower diagonal in italics) and 270 women (values on the upper diagonal in bold).

| M | SD | Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.24 | (0.82) | 1. Anxiety Sensitivity | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| 1.09 | (0.74) | |||||||||||

| 1.76 | (0.68) | 2. Impaired Control | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.14 | −0.04 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| 1.80 | (0.65) | |||||||||||

| 2.00 | (1.58) | 3. Heavy Episodic Drinking | −0.03 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.59 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 2.44 | (1.65) | |||||||||||

| 0.62 | (0.54) | 4. Alcohol-Related Problems | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 0.72 | (0.67) | |||||||||||

| 24.10 | (6.88) | 5. Mother Permissiveness | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.18 | −0.58 | −0.19 |

| 26.32 | (5.94) | |||||||||||

| 25.55 | (8.08) | 6. Father Permissiveness | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.29 | −0.03 | −0.62 |

| 27.18 | (6.38) | |||||||||||

| 34.24 | (8.81) | 7. Mother Authoritativeness | −0.09 | −0.22 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.14 | 1.00 | 0.25 | −0.48 | −0.03 |

| 35.39 | (6.12) | |||||||||||

| 33.28 | (9.01) | 8. Father Authoritativeness | −0.03 | −0.20 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 1.00 | −0.10 | −0.40 |

| 34.60 | (6.34) | |||||||||||

| 31.43 | (8.79) | 9. Mother Authoritarianism | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.39 | −0.07 | −0.15 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.24 |

| 31.47 | (6.66) | |||||||||||

| 32.02 | (9.86) | 10. Father Authoritarianism | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.11 | −0.45 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.37 | 1.00 |

| 33.30 | (7.18) |

Figure 2.

Fit path model for men. Standardized coefficients are shown for men with all exogenous variables allowed to correlate freely in the model.

Model for Men (N=344)

Figure 3.

Fit path model for women. Standardized coefficients are shown for women with all exogenous variables allowed to correlate freely in the model.

Model for Women (N=270)

Table 2.

Gender differences on path coefficients.

We examined structural invariance among the genders by looking at each path in the model. The pathway from AS to IC is stronger for men than for women. The pathway from AS to Heavy Episodic Drinking is stronger for men than for women. The pathway from Father Authoritarianism to Alcohol-Related Problems is stronger for men than women.

| Model | χ 2 | Δχ2 |

|---|---|---|

| Base model (df16) | 10.314 | |

|

| ||

| Parenting Styles to Anxiety Sensitivity | ||

| Mother Permissiveness | 12.336 | 2.022 |

| Father Permissiveness | 12.390 | 2.076 |

| Mother Authoritarianism | 10.330 | <1.000 |

| Father Authoritarianism | 11.110 | <1.000 |

| Mother Authoritativeness | 10.503 | <1.000 |

| Father Authoritativeness | 10.401 | <1.000 |

| Anxiety Sensitivity to Impaired Control | 16.297 | 5.983** |

| Parenting Styles to Impaired Control | ||

| Mother Permissiveness | 11.977 | 1.663 |

| Father Permissiveness | 10.318 | <1.000 |

| Mother Authoritarianism | 10.315 | <1.000 |

| Father Authoritarianism | 10.314 | <1.000 |

| Mother Authoritativeness | 10.540 | <1.00 |

| Father Authoritativeness | 13.038 | 2.724 |

| Impaired Control to Heavy Episodic Drinking | 10.317 | <1.000 |

| Anxiety Sensitivity to Heavy Episodic Drinking | 16.577 | 6.263** |

| Parenting Styles to Heavy Episodic Drinking | ||

| Mother Permissiveness | 10.338 | <1.000 |

| Father Permissiveness | 10.335 | <1.000 |

| Impaired Control to Alcohol-Related Problems | 11.833 | 1,519 |

| Anxiety Sensitivity to Alcohol-Related Problems | 11.599 | 1.285 |

| Parenting Styles to Alcohol-Related Problems | ||

| Mother Authoritarianism | 10.763 | <1.000 |

| Father Authoritarianism | 10.798 | 3.912* |

Direct effects (unstandardized coefficients reported in text) among men

Higher levels of father permissiveness were directly linked to higher levels of AS among men (β = .022, Z = 2.539, p < .011), which in turn were directly linked to more IC (β = .265, Z = 5.985, p < .001). Higher levels of mother permissiveness (β = .021, Z = 2.889, p = .004) were directly linked to more IC among men, while higher levels of father authoritativeness (β = −.014, Z = − 2.309, p = .021) and mother authoritativeness (β = −.021, Z = −1.889, p = .059; trend) were directly related to less IC among men. In turn, higher levels of IC were directly linked to more heavy episodic drinking (β = 1.000, Z = 7.148, p < .001) among men. Higher levels of AS were directly linked to less heavy episodic drinking (β = − .352, Z = −.2.850, p = .004), yet were directly related to more alcohol-related problems (β = .152, Z = 3.382, p = .001) among men. In addition, higher levels of IC (β = .444, Z = 8.771, p < .001) were also directly linked to more alcohol-related problems among men. Moreover, higher levels of father authoritarianism were also directly linked to more alcohol-related problems among men (β =.010, Z = 2.725, p =.006).

Direct effects (unstandardized coefficients reported in text) among women

Regarding direct associations among the variables, standardized coefficients are shown in Figure 3 for women. With respect to the relations between parenting styles and AS, higher levels of mother permissiveness as well as father authoritarianism were directly linked to higher levels of AS among women [unstandardized coefficients (β = .021, Z = 2.088, p = .037; mother permissiveness); (β = .016, Z = 2.142, p = .032; father authoritarianism)]. IC was also directly linked to both more heavy episodic drinking (β = .988, Z = 7.584, p < .001) and alcohol-related problems among women (β = .362, Z = 8.470, p < .001). Higher levels of AS were also directly linked to more alcohol-related problems among women (β = .085, Z = 2.219, p = .026). Nevertheless, higher levels of father authoritarianism were not significantly directly related to more alcohol-related problems among women (β = .001, Z = .226, p = .821).

3.1. Key mediated effects among men

Impaired Control Over Drinking (IC)

Higher levels of father permissiveness were indirectly linked to more IC through more AS (indirect effect = .006; CI 90% [.002, .011]) among men. The amount of variance of IC explained by both parental influences and AS in our model for both men and women resulted in an R2 (variance accounted for) of .051 (Z = 1.717, p = .086) among women, and an R2 of .220 (Z = 5.183, p < .001) among men for IC. This suggests this model is more pertinent to men than to women.

Heavy Episodic Drinking

Higher levels of AS were indirectly linked to more heavy episodic drinking through more IC (indirect effect = .264; CI 90% [.163, .389]). Higher levels of father permissiveness were indirectly linked to less heavy episodic drinking through more AS (indirect effect = −.008; CI 90% [−.018, −.002]). This pattern changes with IC in the pathways such that higher levels of father permissiveness were indirectly linked to more heavy episodic drinking through both more AS and more IC (indirect effect = .006; CI 90% [.002, .012]). Moreover, higher levels of mother permissiveness were indirectly linked to more heavy episodic drinking through more IC (indirect effect = .020; CI 90% [.008, .036]). Unlike permissive parenting, higher levels of father authoritativeness were indirectly linked to less heavy episodic drinking through less IC (indirect effect = −.014; CI 90% [−.026, −.004]).

Alcohol-Related Problems

Higher levels of AS were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more IC (indirect effect = .118; CI 90% [.076, .171). In addition, higher levels of father permissiveness were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more AS (indirect effect = .003; 90% CI [.001, .010]). Further, higher levels of father permissiveness were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through both more AS and more IC (indirect effect = .003; CI 90% [.001, .005]).

Higher levels of mother permissiveness were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more IC (indirect effect = .009; CI 90% [.003, .016]). Unlike permissive parenting, higher levels of father authoritativeness were indirectly linked to fewer alcohol-related problems through less IC (indirect effect = −.006; CI 90% [−.011, −.002]). In addition, higher levels of mother authoritativeness were indirectly linked to fewer alcohol related problems through less IC (indirect effect = −.005; CI 90% [−.010, −.001]).

3.2. Key mediated effects among women

We examined pathways that suggested mediation among women. There were no significant mediated pathways to IC, heavy episodic drinking, nor alcohol-related problems that we can report. A zero was found in each interval, suggesting that there was no evidence of mediation.

4. Discussion

Nichter and Chassin (2015) suggest that while worry is protective of alcohol use outcomes, the experiences of physiological anxiety are positively associated with alcohol involvement. Anxiety sensitivity (AS) is unique in that it reflects a degree of worry about experiencing the physiological effects of anxiety symptoms and the embarrassment that can accompany those symptoms. Our findings here are consistent with the idea that AS is related to a perceived lack of control over future events (Dugas et al., 2001). Our findings extend this idea in a novel way by showing how AS is linked to a perceived lack of control over drinking (i.e., impaired control over drinking, in the future, specifically; part III of the Heather et al., 1993, p.704, measure) and how this link may be particularly problematic for men. Moreover, AS appeared to share the same pattern of relationships to alcohol-related outcomes as internalizing disorders, such as neuroticism and depression. AS may be protective against frequently drinking large amounts of alcohol, but highly related to experiencing a negative alcohol-related consequence when alcohol is used (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007; 2009). Our findings here complement those of DeMartini and Carey (2011) who found that AS indirectly influenced alcohol use through coping and conformity motives. Our finding that AS was predictive of lower levels of heavy episodic drinking among men but not among women is consistent with previous findings that the desire to drink alcohol when an individual is living with an anxious mood manifests more for women than for men (Annis & Graham, 1995; Lau-Barraco et al., 2009; Stewart & Zeitlin, 1995). In the present study, we show for the first time how the relationship between AS and alcohol consumption may not be as simple as a direct negative relationship (similar to neuroticism and depression; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez 2007; 2009), but may actually be indirectly related to more alcohol consumption for males (i.e. heavy episodic drinking) when the mediating mechanism of IC is in the pathway. What our study was not able to answer is what mediates the pathway from AS to alcohol-related problems among women. Thus, future investigations may wish to explore potential mediators of this relationship among women (e.g., ruminating, catastrophizing). Clearly, AS plays an important role in the development and maintenance of alcohol problems among both men and women, but different processes may be involved across genders. In a general sense, our findings provide some additional evidence in favor of the Self-Medication Theory (Hersh & Hussong, 2009) and its impact on escalating and negatively reinforcing heavier drinking and problematic alcohol use, but only among men.

Stewart and colleagues (2001) found that AS was linked to increased drinking behavior among both genders, but via different mediators (through coping motives for women and conformity motives for men). Our results continue to highlight important gender-specific mediation pathways that provide insights into why increased levels of AS may be linked to alcohol-related outcomes (Schmidt et al., 2007; Stewart et al., 2001). Specifically, we found that high levels of AS were related to problematic alcohol use through their association with impaired control over drinking (IC) among males. While higher levels of AS were associated with more IC, which in turn was associated with heavier drinking and more alcohol-related problems, this pattern was robustly true only among men. Our finding that AS was directly linked to IC was robust for men (Z = 6.229) and not for women (Z = 1.703), which is consistent with previous findings regarding stronger and unique associations between AS and alcohol use among men (Schmidt et al., 2007).

Our findings suggest that perceptions of masculine and feminine gender roles have particular relevance in shaping AS in the context of drinking behaviors. In general, men and women adhere to socially prescribed behaviors and traits that are consistent with their gender, which in turn affects how they experience anxiety-related symptoms (Bem, 1981). For example, women report a greater fear of the physical and psychological consequences of anxiety compared to men, who report a greater fear of the social consequences of experiencing anxiety (Kushner et al., 2001; McLean & Anderson, 2009; Stewart et al., 1997). Thus, as men fear appearing anxious, there may be additional motivations to hide those anxious sensations. Drinking alcohol may be an outlet for alleviating or hiding those anxious sensations in a societally appropriate way that is often associated with masculinity (e.g., being able to drink a lot of alcohol is considered manly).

Additionally, societal norms have a profound effect on how men and women approach drinking behaviors. As most men and women do not want to violate gender norms, women may approach drinking with apprehension, while men consume more alcohol per occasion as a sign of manhood (Kerr-Corrêa et al., 2007). In response to anxiety-provoking situations, men are more likely than women to view alcohol as an effective coping strategy (Cooper et al., 1992; McLean & Anderson, 2009). Even though women typically endorse more anxiety-related symptoms, men show stronger relationships with alcohol-related problems when they experience anxiety and are three times more likely to have a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence (Brady & Randall, 1999; Geisner et al., 2004). Women have the option of relying on emotion-focused coping without receiving social disapproval, whereas men may resort to drinking to escape from their feelings and cope with distress (Kerr-Corrêa et al., 2007).

Conceivably, parenting interactions may enhance the link between expressions of anxiety and negative drinking behaviors through modeling. East and colleagues (2007) found that paternal, but not maternal, AS was associated with the expression of offspring AS. In contrast, other researchers (e.g., Graham & Weems, 2015) found that parental AS was only associated with female offspring AS. The links between parental influences and offspring outcomes regarding AS are likely to be complex and require further exploration. Conceivably, for men, drinking may have roots in the inability to cope with anxiety symptoms, which may be shaped by non-structured interactions with their fathers while growing up. Structure and rules may provide male offspring a sense of security about life that is necessary to form appropriate self-regulatory skills, such as regulating their alcohol intake according to non-problematic levels (e.g., no more than two beers per occasion). As hypothesized, permissive parenting by the same-gender parent is related to more AS symptoms. This suggests that parenting with the lack of structure needed to guide behavior can promote feelings of uncertainty and may lead to an increased chance of learning to fear one’s own reactions to anxiety-provoking situations. Further, and more importantly, we found that permissive parents of gender-matched offspring contribute to a number of negative mediators of alcohol use and problems. The extant literature has shown that permissive parenting styles are linked to increased impulsivity (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; Patock-Peckham et al., 2011) and less generalized self-regulation (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001). Although these previous findings concerned externalizing issues involving behavioral control, our novel findings suggest permissive parents of gender-matched offspring can lead to the fear of fear itself (i.e., anxiety sensitivity).

We hypothesized that authoritarian parenting of either gender would be associated with more AS symptoms among offspring. Interestingly, there was a direct link between authoritarian fathers and AS symptoms, but only among women. Our findings for women are consistent with existing literature suggesting that fathers lacking warmth indirectly influence drinking outcomes through internalizing behaviors among their offspring (e.g., neuroticism among men, Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007; depression among both men and women, Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007). Our finding that father authoritarianism was directly related to alcohol-related problems is inconsistent with other studies (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007; 2009), which found that father authoritarianism was indirectly (but not directly) related to alcohol-related problems through mediating mechanisms such as depression and self-esteem. Our current study found a direct link without these specific mediators (e.g., depression) in our current model. Authoritarianism is a style of parenting that includes structure but lacks warmth. Previous research has found that depression mediated the indirect link from father authoritarianism to alcohol-related problems among men (see Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007).

Parenting styles encapsulate how a parent interacts with their offspring. Our study suggests that parenting styles have distal associations with alcohol-related outcomes associated with AS and IC. Although parenting can be measured in aggregate form, disaggregating the effects of parenting practices by mothers and fathers on their offspring’s behaviors has been shown to be important (King & Chassin, 2004; Luk et al., 2010; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; van der Vorst et al., 2006). We found that permissive parenting had unique effects on gender-matched offspring. According to socialization theories, children tend to form closer relationships with their same-sex parent (Laursen & Collins, 2004) and may rely more heavily on them for guidance and structure. From a Social Learning Theory Perspective (see Bandura & Walters, 1963), children observe the attitudes and behaviors of their same-sex parent in order to learn how to model their own behavior (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; McHale et al., 2003).

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations. First, though guided by a comprehensive, theoretical framework, which points to the temporal ordering of events, we used cross-sectional data to test our model, limiting our ability to make causal statements. It is likely that our study did not capture the dynamic interactions between parents and their offspring over time and we acknowledge that parents may adapt their parenting styles in response to the unique characteristics of their offspring. Second, we only measured the perspective of offspring and not parents. Although we did not ask parents to report on their parenting styles, child reports have been found to have stronger connections to their outcomes compared with the parent’s own report (Latendresse et al., 2009). Usually parent and child agreement regarding the parent’s style of parenting ranges from .19 to .43 and varies very little among countries (see Tein et al., 1994; Rebholz et al.’s meta-analysis, 2014). Future research examining AS and its relation to parenting and drinking outcomes should consider using prospective data and multiple sources of data on parenting behaviors to address these limitations and better understand the developmental patterns leading to internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Another limitation of the present study is that we did not use the newer Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 measure (Taylor et al., 2007), which includes factors of AS that involve physical, cognitive, and social concerns. These distinct facets of AS might help therapists to further fine tune targets for CBT. Another future direction for research would be to test AS over and above constructs such as neuroticism or the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) along the IC pathway to alcohol-related problems.

Moreover, future investigations should explore mediators besides IC to explain the AS to alcohol-related problems link among women. In addition, because Olthuis and colleagues (2015) showed that tailored intervention strategies may prove effective in preventing problematic alcohol use for both men and women with a heightened sensitivity to anxiety, future investigations may wish to further explore this avenue more fully regarding interventions for IC- related issues.

Despite these limitations, our findings here are novel in that they show the unique and direct association between AS and IC, revealing a common underlying mechanism of an inability to regulate control over both internalizing (e.g., AS) and externalizing (e.g., drinking past limits; IC) symptoms. Thus, our findings elucidate the issue of how internalizing symptoms sometimes turn into externalizing behaviors along the alcohol-related problems pathway. Additionally, we found that the direct link between AS and IC was extremely robust for men (Z = 5.985) and non-significant for women (Z = 1.692). Our finding suggests that AS is a much more serious phenomenon regarding dysregulated drinking or IC among men. Further, we showed that AS functions similarly to internalizing disorders. For instance, we found that AS was directly related to more alcohol-related problems for both men and women but less heavy-episodic drinking for men. However, we found that AS was indirectly linked to more heavy-episodic drinking for men when the mediating mechanism of IC was in the pathway. This has significant implications for impaired control over drinking, particularly among men who are unable to manage their anxiety. We also found a direct link between permissive parenting and AS for gender-matched offspring, but only a direct link between authoritarian fathers and AS in women. Our inclusion of fathers’ parenting style is important because fewer than 20% of all the studies on parenting behaviors include or focus on fathers, despite the fact that the effect of a lack of support and structure by fathers was larger than it is for mothers particularly among sons (see Hoeve et al.’s meta-analysis, 2009). Finally, simultaneous modeling in the current study supports the importance of differentiating between several core alcohol-related outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the current study provides support for distal associations of parenting styles in the development of alcohol problems through AS and IC. Our findings suggest that authoritarian and permissive parenting styles may increase the likelihood of increased levels of AS, which in turn may contribute to problematic drinking behaviors and outcomes. Permissive parenting of the same-gender directly contributed to AS, suggesting an offspring-parent gender match. Our key finding is that men with elevated AS may be at a greater risk for alcohol problems by their uncontrolled approach to drinking, and this finding should be more thoroughly examined in future studies involving clinical samples. Accordingly, clinicians may need to assess for AS when working with male patients presenting with maladaptive alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Burton Family Foundation grant to the Social Addictions Impulse Lab, NIH/NIAA grant K01AA024160 to J. A. Patock-Peckham and R21AA023368 to R. F. Leeman. J. W. Luk’s effort on this project was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- Albano AM, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Childhood anxiety disorders. Child Psychopathology. 2003;2:279–329. [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Capron DW, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Unique relations among anxiety sensitivity factors and anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(2):266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Graham JM. Profile types of the Inventory of Drinking Situations: Implications for relapse prevention counseling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9(3):176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Walters RH. Social Learning and Personality Development. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston; New York: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4(1):1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review. 1981;88(4):354. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;22(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Lond JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57(1):110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron DW, Cougle JR, Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE, Schmidt NB. An interactive model of anxiety sensitivity relevant to suicide attempt history and future suicidal ideation. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(2):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(1):3. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Vassileva J. Differential sensitivity to alcohol reinforcement in groups of men at risk for distinct alcoholism subtypes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22(3):585–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4(2):123. [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Enns MW, Taylor S. The effect of rumination as a mediator of elevated anxiety sensitivity in major depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25(5):525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Votruba-Drzal E, Silk JS. Trajectories of internalizing symptoms from early childhood to adolescence: Associations with temperament and parenting. Social Development. 2015;24(3):501–520. [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, Carey KB. The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: A Critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(1):169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Hausheer R, Esp S. Sex-specific parental behaviors and attitudes as predictors of alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences among ninth grade students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling. 2015;1(2):100–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Gosselin P, Ladouceur R. Intolerance of uncertainty and worry: Investigating specificity in a nonclinical sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25(5):551–558. [Google Scholar]

- East AJ, Berman ME, Stoppelbein L. Familial association of anxiety sensitivity and psychopathology. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24(4):264–267. doi: 10.1002/da.20227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;27(6):495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(5):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RA, Weems CF. Identifying moderators of the link between parent and child anxiety sensitivity: The roles of gender, positive parenting, and corporal punishment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43(5):885–893. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9945-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor C. Predictors of panic attacks in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(2):207–214. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Tebbutt JS, Mattick RP, Zamir R. Development of a scale for measuring impaired control over alcohol consumption: a preliminary report. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1993;54(6):700. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh MA, Hussong AM. The association between observed parental emotion socialization and adolescent self-medication. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(4):493–506. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Semon Dubas J, Eichelsheim VI, van der Laan PH, Smeenk W, Gerris JRM. The relationship between parenting and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt G, Asmussen FV, Moloney M, editors. Rethinking gender within alcohol and drug research. Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50(6):685–692. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.978635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41(2):49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr-Corrêa F, Igami TZ, Hiroce V, Tucci AM. Patterns of alcohol use between genders: A cross-cultural evaluation. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;102(1):265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Guomo L, Hasin DS. Birth cohort effects and gender differences in the alcohol epidemiology: A review and synthesis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(12):2102–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Chassin L. Mediating and moderated effects of adolescent behavioral undercontrol and parenting in the prediction of drug use disorders in emerging adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(3):239. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Thuras P, Abrams K, Brekke M, Stritar L. Anxiety mediates the association between anxiety sensitivity and coping-related drinking motives in alcoholism treatment patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(6):869–885. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parental socialization and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors: Predictive disparities in parents’ versus adolescents’ perceptions of the parenting environment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(2):232–244. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C, Skewes MC, Stasiwicz PR. Gender differences in high-risk situations for drinking: Are they mediated by depressive symptoms? Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Collins WA. Parent-child communication during adolescence. The Routledge Handbook of Family Communication. 2004:333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Patock-Peckham JA, Potenza MN. Impaired control over alcohol use: An under-addressed risk factor for problem drinking in young adults? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20(2):92–106. doi: 10.1037/a0026463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Toll BA, Taylor LA, Volpicelli JR. Alcohol-induced disinhibition expectancies and impaired control as prospective predictors of problem drinking in undergraduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):553. doi: 10.1037/a0017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Farhat T, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton BG. Parent–child communication and substance use among adolescents: Do father and mother communication play a different role for sons and daughters? Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(5):426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AB, Baker JM, Stewart SH, Skinner M. Effects of alcohol on the response to hyperventilation of participants high and low in anxiety sensitivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(11):1656–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New York, NY; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Whiteman SD. The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2003;12(1):125–148. [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(6):496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(2):155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Racusin CA, Phelan JE, Rudman LA. When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2010;11(2):140–151. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nichter B, Chassin L. Separate dimensions of anxiety differentially predict alcohol use among male juvenile offenders. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;50:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Mackinnon SP, Stewart SH. CBT for high anxiety sensitivity: Alcohol outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;46:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J, Balhorn ME, Nagoshi CT. A social learning perspective: a model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use and problems. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25(9):1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(2):117–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, parent bonds, depression, and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):297–306. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. Mediational links among parenting styles, perceptions of parental confidence, self-esteem, and depression on alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(2):215–226. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. The gender specific mediational pathways between parenting styles, neuroticism, pathological reasons for drinking, and alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(3):312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, King KM, Morgan-Lopez AA, Ulloa EC, Filson Moses JM. Gender-specific mediational links between parenting styles, parental monitoring, impulsiveness, drinking control, and alcohol-related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(2):247–258. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S. Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991;11(2):141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, McNally RJ. The expectancy model of fear. In: Reiss S, Bootzin RR, editors. Theoretical Issues in Behavior Therapy. Academic Press; New York: 1985. pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz CE, Chinapaw MJM, van Stralen MM, Bere E, Bringolf B, Bourdeaudhuij ID, … Velde SJ. Agreement between parent and child report on parental practices regarding dietary, physical activity and sedentary behaviours: The ENERGY cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:918–932. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Stein MB. Developmental antecedents of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17(3):253–269. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Keough ME. Anxiety sensitivity as a prospective predictor of alcohol use disorders. Behavior Modification. 2007;31(2):202–219. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annual Review Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Taylor S, Baker JM. Gender differences in dimensions of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11(2):179–220. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zeitlin SB. Anxiety sensitivity and alcohol use motives. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9(3):229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual differences. 2001;31(2):157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Jang KL, Stewart SH, Stein MB. Etiology of the dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: A behavioral–genetic analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(5):899–914. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, Tein J. Tests of the three-path mediated effects. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11(2):241–269. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, … Cardenas SJ. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(2):176–188. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein J, Roosa MW, Michaels M. Agreement between parent and child reports on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(2):341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Timpano KR, Carbonella JY, Keough ME, Abramowitz J, Schmidt NB. Anxiety sensitivity: An examination of the relationship with authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parental styles. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2015;29(2):95–105. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.29.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Stipleman BA, Salters-Pedneault K, Gratz KL. An examination of recent non-clinical panic attacks, panic disorder, anxiety sensitivity, and emotion regulation difficulties in the prediction of generalized anxiety disorder in an analogue sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst H, Engels RC, Meeus W, Deković M. Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: a longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(2):107–116. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis CM, van Steensel FJA, Bögels SM. Parenting clinically anxious versus healthy control children aged 4–12 years. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;32:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Quilty LC, Hendershot CS. Alcohol sensitivity moderates the indirect associations between impulsivity traits, impaired control over drinking, and drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2015;76:278–286. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MC, Stewart SH. The role of anxiety sensitivity components in mediating the relationship between childhood exposure to parental dyscontrol and adult anxiety symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25(3):167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Stewart S, Birch C, Bernier D. Brief CBT for high anxiety sensitivity decreases drinking problems, relief alcohol outcome expectancies, and conformity drinking motives: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15(6):683–695. [Google Scholar]

- Watt MC, Stewart SH, Cox BJ. A retrospective study of the learning history origins of anxiety sensitivity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(5):505–525. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt MG, Wood W. Self-regulation of gendered behavior in everyday life. Sex Roles. 2010;62(9–10):635–646. [Google Scholar]

- Wood W, Rhodes N. Gender, Interaction, and Inequality. Springer; New York: 1992. Sex differences in interaction style in task groups; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zeinali A, Sharifi H, Enayati M, Asgari P, Pasha G. The mediational pathway among parenting styles, attachment styles and self-regulation on addiction susceptibility. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2011;16(9):1105–1121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]