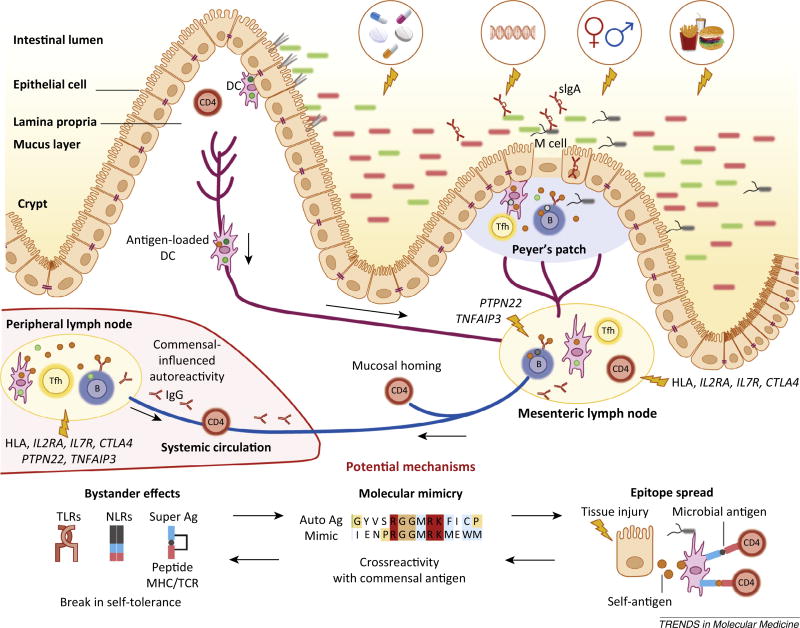

Figure 3.

The gut microbiota impinges on non-gut autoimmunity. The gut microbiota balances the development of organ-specific and systemic autoimmunity in animal models. Dietary, antibiotic, genetic, hormonal, and hygienic factors affect the composition of the intestinal microbiota. Altered microbial community composition or function (dysbiosis) influences immune homeostasis locally and systemically. Genetic susceptibility (particularly via HLA haplotypes and genes regulating inflammation), combined with barrier disruption and dysbiosis, will increase the propensity of antigen-presenting cells [e.g., dendritic cells (DCs) or B cells] to take up antigen at different sites (lamina propria and Peyer’s patches), become activated, and present antigen to cognate T cells in secondary lymphoid organs. Follicular TH cells (TFH; shown as Tfh) cells help B cells in the germinal centers of lymph nodes or Peyer’s patches to produce different classes of antibodies, such as secretory IgA (sIgA) in the gut and IgG and IgA in the periphery. Activated immune cells traffic from the intestine to the mesenteric lymph nodes where they become imprinted with intestinal-homing markers. Some cells will also circulate systemically entering peripheral lymph nodes and target tissues. The development of autoreactive lymphocytes is proposed to occur due to three mechanisms: bystander effects, molecular mimicry, and epitope spreading. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and can also affect barrier organ autoimmunity. Each of these three mechanisms applied to commensals could be implicated in the development of non-barrier organ autoimmune diseases, for example type 1 diabetes (T1D), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS), or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), similarly to transient autoimmune syndromes induced by pathogenic infections affecting for instance the joints (rheumatic fever) or nervous system (Guillan–Barré syndrome). Without genetic susceptibility, the proposed anti-commensal responses would be limited and lead to no overt autoimmunity. In a genetically predisposed host, several scenarios can occur depending on the genetics and pathobiont/ symbiont balance. Dysbiosis could be sustained by a genetic predisposition that leads to innate or B cell hyper-responsiveness, for example via polymorphisms in protein tyrosine phosphatase 22 (PTPN22) or tumor necrosis factor α-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3). Without overt dysbiosis, antigen-specific recognition of commensals could lead to autoimmunity via crossreactivity if HLA polymorphisms or genetically encoded defects in Tregs or T cell homeostasis are present, for example in interleukin-2 receptor a (IL2RA), interleukin-7 receptor (IL7R), or cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4).