Abstract

Development of nucleic acid base pair analogues that use new modes of molecular recognition is important for fundamental research and practical applications. The goal of this study was to evaluate 2-methoxypyridine as a cationic thymidine mimic in the A-T base pair. The hypothesis was that including protonation in the Watson-Crick base pairing scheme could enhance the thermal stability of DNA double helix without compromising the sequence selectivity. DNA and peptide nucleic acid (PNA) sequences containing the new 2-methoxypyridine nucleobase (P) were synthesized and studied using UV thermal melting and NMR spectroscopy. Introduction of P nucleobase caused a loss of thermal stability by ~10 °C in DNA-DNA duplexes and ~20 °C in PNA-DNA duplexes over a range of mildly acidic to neutral pH. Despite the decrease in thermal stability, the NMR structural studies showed that P-A formed the expected protonated base pair at pH 4.3. Our study demonstrates the feasibility of cationic unnatural base pairs; however, future optimization of such analogues will be required.

Keywords: Modified nucleobase, Unnatural base pair, Cationic base pair, DNA duplex, Peptide nucleic acid

Graphical Abstarct

Thermodynamic and NMR structural studies show that 2-aminopyridine forms a protonated base pair with adenosine at pH 4.3. The work demonstrates the feasibility of cationic unnatural base pairs.

Introduction

Watson-Crick base pairing is fundamental to structure and molecular recognition of nucleic acids. Development of novel unnatural Watson-Crick base pair analogues is an area of active research due to potential applications in biochemistry, biotechnology and medicinal chemistry.[1] Modified nucleosides that extend and diversify Watson-Crick base pairing schemes are used in novel systems for genetic information storage and replication,[1] antiviral drug development,[2] nanotechnology and materials science,[3] selection of advanced nucleic acid aptamers and catalysts,[4] and optimization of antisense oligonucleotides.[5] Most of these applications benefit from modifications that enhance the thermal stability of nucleic acid duplexes.

A wide variety of modified nucleobases have been synthesized to expand the genetic alphabet or enhance the thermal stability and sequence specificity of DNA and RNA duplexes. Prominent examples include (Scheme 1): artificially expanded genetic information system (AEGIS) developed by Benner (dP-dZ);[6] novel base pairing systems that rely entirely on hydrophobic interactions developed in laboratories of Kool (dF-dZ),[7] Hirao (dDs-dPx),[8] and Romesberg (dNaM-dTPT3);[9] nucleobases forming four hydrogen bonds (ImON-NaNO);[10] and size expanded nucleobases (xA-dT, and others).[11] DNA duplex stability can be enhanced by improving the π–π stacking interactions as in xA-dT base pairs and by increasing the number of hydrogen bonds as in ImON-NaNO base pairs (Scheme 1). The purpose of our study was to develop novel cationic nucleobase analogues that could potentially enhance the Watson-Crick recognition using electrostatic attraction.

Scheme 1.

Examples of unnatural base pairs.

The idea of using electrostatic attraction between the positively charged base and the negatively charged sugar-phosphate backbone was inspired by our recent work on triple helical recognition of double-stranded RNA using peptide nucleic acid (PNA) containing 2-aminopyridine (M) nucleobase.[12] Under physiological conditions, M (pKa ~ 6.7) is partially protonated, thus, serving as an analogue of protonated cytosine in the Hoogsteen triplet (Scheme 2). The key inspiring observation was that M-modified cationic PNAs had significantly higher affinity for double-stranded RNA than PNAs containing neutral nucleobases with the same hydrogen bonding ability as M.[12] Despite the cationic nature, M-modified PNAs maintained excellent sequence selectivity. These observations led us to hypothesize that similar cationic Watson-Crick nucleobase analogues could also enhance the affinity of DNA and PNA probes for single-stranded nucleic acid targets without compromising sequence selectivity.

Scheme 2.

Design of the cationic nucleobase analogue P.

To test our hypothesis, we prepared DNA and PNA analogues having 2-methoxypyridine (P) nucleobase (Scheme 2), which upon protonation is expected to mimic thymidine in the Watson-Crick T-A base pair. Compared to M (pKa ~ 6.7), the pKa ~ 3.3[13] for P was not favourable for duplex formation at physiological conditions. However, we envisioned that using buffers with lower pH would allow the proof-of-concept studies. The advantage of using P was the easy access to synthetic precursors required for preparation of the modified DNA and PNA.

Results and Discussion

For our proof-of-concept studies we synthesized DNA and PNA model oligonucleotides carrying the P nucleobase. PNA is a DNA analogue that has the entire sugar-phosphate backbone replaced by neutral N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine linkages. Because of the lack of electrostatic repulsion, duplexes of PNA with complimentary DNA and RNA are of higher stability and sequence selectivity than those formed by native oligonucleotides, making PNA a highly useful probe in molecular biology and biotechnology.[14] From the perspective of cationic nucleobase modifications, the key difference between DNA and PNA is that the neutral backbone of the latter avoids formation of zwitterionic compounds.

Synthesis of 2-methoxypyridine PNA monomer 4

The synthesis of 2-methoxypyridine PNA monomer started with carbodiimide-mediated coupling between the commercially available 2-(6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)acetic acid 1 and Fmoc protected PNA backbone 2, which was synthesized according to the previously reported literature procedure (Scheme 3).[15] Optimization of the original procedures involved the use of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) instead of N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), which simplified purification and improved the yield of compound 3.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of PNA Monomer 4: (a) EDC, HOBt, DMF, 40 °C, ~16 h; (b) Pd(PPh3)4, N-ethylaniline, THF, rt, 18 h.

Removal of the allyl protecting group in the presence of catalytic Pd and N-ethylaniline gave the desired PNA monomer 4 in 77% yield. NMR characterization of compounds 3 and 4 was complicated by signal doubling due to the presence of two amide rotamers (for details, see Supporting Information).

Synthesis of 2-methoxypyridine DNA monomer 12

Because of their importance in medicinal chemistry, the synthesis of C-nucleosides has been well studied.[16] Inspired by the work of Hocek and co-workers,[17] we used an approach involving the Heck reaction[18] as the key step for the synthesis of C-nucleoside 10. The synthesis started with Pd(OAc)2 catalyzed coupling of glycal 6 with commercially available iodide 7 in the presence of AsPh3 and Ag2CO3 in chloroform (Scheme 4). Using chloroform as a solvent was important for achieving reasonable yields of 8. The Heck reaction of 6 and 7 in DMF at 60 °C overnight gave ketone 9 directly but in low yields.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of DNA Monomer 12: (a) Pd(OAc)2, AsPh3, CHCl3, Ag2CO3, 60 °C, ~16 h; (b) Et3N · 3HF, THF, 0 °C, 5 min; (c) NaBH(OAc)3, AcOH/CH3CN (2:1), 0 °C, 5 min; (d) DMTrCl, pyridine, 0 °C to rt, ~16 h; (e) 2-cyanoethyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetraisopropylphosphorodiamidite, H-tetrazole, dry DCM, rt, 5.5 h.

Glycal 6[19] was synthesized in four steps and 46% yield from deoxyribose following the procedure developed by Minuth and Richert.[20] In our hands, the preparation of glycal 6 was complicated by formation of a furan by-product 5. To minimize the formation of 5, the optimized procedures for synthesis and purification of 6 (Supporting Information) should be followed precisely. Compound 6 should be stored at −20 °C and the quality should be checked by NMR (TLC does not separate 5 and 6) before the Heck reaction.

After removing the TBS group with Et3N·3HF in THF, ketone 9 was reduced without isolation with NaBH(OAc)3 in a mixture of acetic acid and acetonitrile (2:1) giving the 2-methoxypyridine nucleoside 10 in 73% yield over the two steps. The protection of the 5′-OH with dimethoxytrityl (DMT) group and reaction of the 3′-OH with 2-cyanoethyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetraisopropylphoshorodiamidite gave the desired phosphoramidite 12.

Synthesis and thermal stability of P-modified duplexes

Monomers 4 and 12 were used to synthesize PNA and DNA sequences containing the new 2-methoxypyridine (P) nucleobase using standard procedures on an Expedite 8909 DNA/PNA synthesizer. The synthetic PNA and DNA sequences were purified by reverse phase HPLC and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to confirm the identity of compounds. The thermal stability of PNA-DNA and DNA-DNA duplexes was studied using UV thermal melting in 0.1 M citric acid/sodium citrate buffers over a pH range of 3.3 to 6.3 and a phosphate buffer at physiological salt concentration and pH of 7.4. The acidic buffers were used to enable protonation of 2-methoxypyridine (pKa ~ 3.3) nucleobase and formation of the novel unnatural P-A base pair.

Using monomer 4, we synthesized PNA2 and PNA3 containing one and two P modifications, respectively (Figure 1). The thermal stability of the modified duplexes formed by PNAs and the complementary DNA (cDNA1) was studied using UV-thermal melting in comparison to the duplex formed by the unmodified PNA1 (Figures 1 and 2). All PNA-cDNA1 duplexes showed similar trend where the melting temperature (Tm) slightly increased with decreasing pH, reached the peak at pH 4.3 and dropped again at pH 3.3 (Figure 2). At pH 4.3 the Tm of modified duplex formed by PNA2 having one P modification was 40.5 °C, which was ~20 °C lower than the Tm of unmodified duplex formed by PNA1 (61.1 °C). The Tm decreased further to 29.2 °C upon introduction of the second P modification in PNA3. Similar trends were observed at other pH values.

Figure 1.

UV-thermal melting curves of duplexes formed by PNA1–3 and the complementary DNA at pH 4.3.

Figure 2.

UV-melting temperatures (Tm, °C) monitored at 270 nm of duplexes formed between PNA1-PNA3 with the complementary cDNA1, 3′-GGACAGAACGGA; pH 3.3 – 6.3 in 100 mM citrate buffer; pH 7.4 in 2 mM MgCl2, 90 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 50 mM K2HPO4.

Using monomer 12, we synthesized DNA2 having the same sequence and P modification pattern as PNA2 (Figure 3). In contrast to PNA-DNA duplexes that had the highest Tm at pH 4.3, the thermal stability of P-modified DNA-DNA duplexes peaked at pH 6.3 and we did not obtain analyzable melting transitions at pH 3.3. The Tm of the unmodified duplex was 54.4 °C. The corresponding Tm of modified DNA2 duplex with cDNA1 was 43.4 °C at pH 6.3. Thus, the introduction of one P nucleobase into the DNA duplex caused a drop in Tm by 11 °C.

Figure 3.

UV-melting temperatures (Tm, °C) monitored at 270 nm of duplexes formed between DNA1 and DNA2 with the complementary cDNA1, 3′-GGACAGAACGGA; pH 4.3 – 6.3 in 100 mM citrate buffer; pH 7.4 in 2 mM MgCl2, 90 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 50 mM K2HPO4.

To expand our thermodynamic studies to molecular detail structural studies of P-modified oligonucleotides, we synthesized the self-complementary DNA4 5′-GCGPGATCACGCA-3′, which has dangling A bases at the ends of the duplex (Figure 4 and 5D). The duplex was designed to place a single P-A pair within a Watson-Crick context with low favorability for hairpin formation or end-to-end stacking. Similar to DNA2, incorporation of P-modified monomer in DNA4 decreased the Tm by 10 °C at pH 4.3, and by 15–20 °C at pH 5.3, 6.3 and 7.4 (Figure 4). The Tm of unmodified DNA3-DNA3 and P-modified DNA4-DNA4 increased with increasing concentration of strands (Tables S11 and S16), as expected for duplex (but not hairpin) formation.

Figure 4.

UV-melting temperatures (Tm, °C) monitored at 270 nm of duplexes formed by the self-complementary DNA3 and DNA4; pH 4.3 – 6.3 in 100 mM citrate buffer; pH 7.4 in 2 mM MgCl2, 90 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 50 mM K2HPO4.

Figure 5.

NMR data and models of the duplex (dGCGPGATCACGCA)2 at pH 4.3 (A) 2D NOESY spectrum at −2.5 °C with mixing time 100 msec. Red circles indicate cross-peaks which are particularly important in defining the P-A pair. (B) Double hydrogen-bond P-A pair calculated by simulated-annealing using NMR restraints and with PN1 charge increased to simulate protonation at that site. The NMR-derived minimum and maximum P-CH3 to AH61 distances are indicated by arcs. (C) Single hydrogen-bond P-A pair calculated by simulated-annealing using NMR restraints (excluding the P-CH3 to AH61 restraint) and with PN1 charge as expected if this site were not protonated. The lack of an NOE between PH6 and AH61, indicated in (A), is not consistent with the 3 Å separation in this model. (D) Secondary structure and 3D model of entire duplex (double hydrogen-bond P-A pair from part B).

NMR structural studies of a P-modified DNA duplex

Structure of the P-A pair was further examined with NMR spectroscopy of a self-complementary duplex DNA4 (Figure 5D) at two pHs and three temperatures. The data at pH 4.3 indicate a single conformation of the P-A pair with close contacts between A amino protons and P methoxy protons, between AH2 and PH6, and between PH3 and P-CH3 (Figure 5A). These contacts are consistent with the double hydrogen-bond arrangement proposed above.

Simulated annealing calculations using all NMR-derived distance restraints, loose backbone torsion restraints and electronic charge for PN1 increased to simulate protonation yielded the double hydrogen-bond model in Figure 5D with P-A pair shown in Figure 5B. An alternative conformation with a single hydrogen-bond P-A pair was obtained by modeling with a negative charge at PN1 and without the P-CH3 to A-amino distance restraint (Figure 5C). However, the single hydrogen-bond conformation results in a 3 Å distance between PH6 and A-amino, which is inconsistent with the lack of a NOESY cross-peak between these atoms (Figure 5A) and a 4.7 Å distance between A amino and P methoxy protons which is beyond the maximum distance indicated by the NMR data (Figure 5C). All other residues form the expected Watson-Crick base-pairs.

NMR data show that at pH 6.3 the P-A pair exists in dynamic equilibrium between at least two conformations while all the other residues remain in stable Watson-Crick base-pairs. Multiple P-A conformations are indicated by broad resonances at low temperature for AH2, PH3, and PH4 which narrow at high temperature (Figure 6). The NOE interaction between AH2 and PH6 is still present, although the intensity is reduced approximately three-fold (~20% distance increase) relative to pH 4.3. This NOE could be consistent with both the single and double hydrogen-bond P-A pairs (Figure 5B,C), but no signal for A amino can be identified. Interestingly, P4H6 shows stronger NOE cross-peaks to H1′, H2′ and H2″ of residue G3 than the NOEs observed at pH 4.3. These stronger cross-peaks likely facilitate spin-diffusion resulting in the weak G3H8–P4H6 cross-peak (Figure 6) and suggest that one of the conformations sampled at pH 6.3 involves movement of the P residue out towards the major groove. Further, the upfield shift of A9H2 caused by increased pH is consistent with reduced ring current effects expected with loss of the P-A pair.

Figure 6.

Slices from 2D NOESY spectra of (dGCGPGATCACGCA)2; slices are taken at the frequency of P4H6. Labeled peaks indicate NOE cross-peak from P4H6 to the indicated proton. An * indicates residue in the opposite strand. Temperature and pH are (A) 1 °C and 4.3; (B) 30 °C and 4.3; (C) 1 °C and 6.3; (D) 30 °C and 6.3. Mixing time is 150 msec.

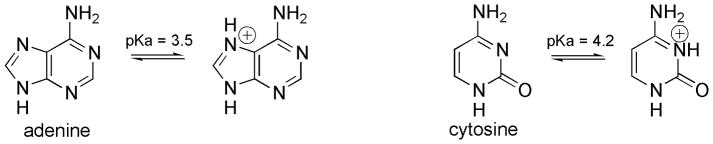

While using lower pH buffers allowed formation of the proposed protonated P-A pair, this is less than ideal even for basic studies because of the ambiguity of protonation of other nucleobases. At low pH, cytosine and adenine can be protonated (Scheme 5) which would interfere with formation of the Watson-Crick base pairs.[21] On the other hand, A-C, C-C and A-G mismatches are stabilized by protonation under low pH conditions.[22] The complexity of protonation is further increased in DNA duplex, because stacking of nucleobase raises their pKa values. While our results demonstrate formation of the protonated P-A pair, the future development of such unnatural base pairs should focus on heterocyclic systems having pKa values suitable for protonation under physiological conditions.

Scheme 5.

Protonation of A and C nucleobases.

Conclusions

The NMR structural studies suggest that the P-A pair does form as proposed at pH 4.3; however, the base pairing becomes dynamic at higher pH. The UV thermal melting data show that the P-A pair contributes little to the thermal stability of the duplex, which is in large part due to unfavorable protonation of P having pKa ~ 3.3. Taken together, our thermodynamic and NMR structural studies demonstrate that cationic Watson-Crick like unnatural base pairs are potentially useful modifications in DNA and PNA, but further optimization of pKa is required to unlock their potential. As demonstrated in our earlier studies,[12] pKa may be used as a rough guideline in designing new cationic base pairs; however, experimental verification will be required due to pKa perturbation in stacked helical nucleic acids.

Experimental Section

For experimental details, see Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from US National Institutes of Health (R01 GM71461). The 600 MHz instrument at Binghamton University is supported by US National Science Foundation (CHE-0922815).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) Armitage BA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tyagi S. Nat Methods. 2009;6:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Zengeya T, Gupta P, Rozners E. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:12593–12596. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Muse O, Zengeya T, Mwaura J, Hnedzko D, McGee DW, Grewer CT, Rozners E. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1683–1686. doi: 10.1021/cb400144x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li M, Zengeya T, Rozners E. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8676–8681. doi: 10.1021/ja101384k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ensslen P, Wagenknecht H-A. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2724–2733. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Zhang L, Yang Z, Trinh TL, Teng IT, Wang S, Bradley KM, Hoshika S, Wu Q, Cansiz S, Rowold DJ, McLendon C, Kim MS, Wu Y, Cui C, Liu Y, Hou W, Stewart K, Wan S, Liu C, Benner SA, Tan W. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:12372–12375. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sefah K, Yang Z, Bradley KM, Hoshika S, Jimenez E, Zhang L, Zhu G, Shanker S, Yu F, Turek D, Tan W, Benner SA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1449–1454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311778111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hollenstein M, Hipolito CJ, Lam CH, Perrin DM. ACS Combinatorial Science. 2013;15:174–182. doi: 10.1021/co3001378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gawande N, Rohloff JC, Carter JD, von Carlowitz I, Zhang C, Schneider DJ, Janjic N. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:2898–2903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615475114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Rohloff C, Gelinas AD, Jarvis TC, Ochsner UA, Schneider DJ, Gold L, Janjic N. Mol Ther-Nucleic Acids. 2014;3:e201. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wan WB, Seth PP. J Med Chem. 2016;59:9645–9667. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z, Chen F, Alvarado JB, Benner SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15105–15112. doi: 10.1021/ja204910n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kool ET. AccChemRes. 2002;35:936–943. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Hirao I, Mitsui T, Kimoto M, Yokoyama S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15549–15555. doi: 10.1021/ja073830m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kimoto M, Kawai R, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e14/11–e14/19. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Degardin M, Lavergne T, Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Ordoukhanian P, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:826–829. doi: 10.1021/ja408814g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hikishima S, Minakawa N, Kuramoto K, Fujisawa Y, Ogawa M, Matsuda A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:596–598. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Gao J, Lynch SR, Saito YD, Maynard L, Kool ET. Science. 2003;302:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.1088334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Zengeya T, Gupta P, Rozners E. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:12593–12596. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Muse O, Zengeya T, Mwaura J, Hnedzko D, McGee DW, Grewer CT, Rozners E. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1683–1686. doi: 10.1021/cb400144x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hnedzko D, McGee DW, Karamitas YA, Rozners E. RNA. 2017;23:58–69. doi: 10.1261/rna.058362.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogretir C, Ozogut D, Yarligan S, Arslan T. J Mol Struct Theochem. 2006;759:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freier SM, Driver DA, Berg RH, Kim SK, Norden B, Nielsen PE. Nature. 1993;365:566–568. doi: 10.1038/365566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nielsen E, Egholm M, Berg RH, Buchardt O. Science. 1991;254:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nielsen E. In: Chem Biol Artif Nucleic Acids. Egli M, Herdewijn P, editors. Verlag Helvetica Chimica Acta; Zurich, Switzerland: 2012. pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Wojciechowski F, Hudson RHE. J Org Chem. 2008;73:3807–3816. doi: 10.1021/jo800195j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hnedzko D, Cheruiyot SK, Rozners E. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2014;58:4.60.1–4.60.23. doi: 10.1002/0471142700.nc0460s58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Stambasky J, Hocek M, Kocovsky P. Chem Rev. 2009;109:6729–6764. doi: 10.1021/cr9002165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wellington W, Benner SA. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2006;25:1309–1333. doi: 10.1080/15257770600917013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Joubert N, Pohl R, Klepetarova B, Hocek M. J Org Chem. 2007;72:6797–6805. doi: 10.1021/jo0709504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Joubert N, Urban M, Pohl R, Hocek M. Synthesis. 2008:1918–1932. [Google Scholar]; c) Kubelka T, Slavetinska L, Eigner V, Hocek M. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:4702–4718. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40774h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Heck RF, Nolley JP., Jr J Org Chem. 1972;37:2320–2322. [Google Scholar]; b) Schoenberg A, Heck RF. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:7761–7764. [Google Scholar]; c) Beletskaya P, Cheprakov AV. Chem Rev. 2000;100:3009–3066. doi: 10.1021/cr9903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Johansson Seechurn CC, Kitching MO, Colacot TJ, Snieckus V. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:5062–5085. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron MA, Cush SB, Hammer RP. J Org Chem. 1997;62:9065–9069. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minuth M, Richert C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:10874–10877. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Costantino L, Vitagliano V. Biopolymers. 1966;4:521–528. doi: 10.1002/bip.1966.360040504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dubey K, Tripathi DN. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2005;42:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Brown T, Leonard GA, Booth ED, Kneale G. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:437–440. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90320-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gao X, Patel DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:5178–5182. [Google Scholar]; c) Brown T, Leonard GA, Booth ED, Chambers J. J Mol Biol. 1989;207:455–457. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Leonard A, Booth ED, Brown T. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5617–5623. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) SantaLucia J, Jr, Turner DH. Biopolymers. 1998;44:309–319. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)44:3<309::AID-BIP8>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.