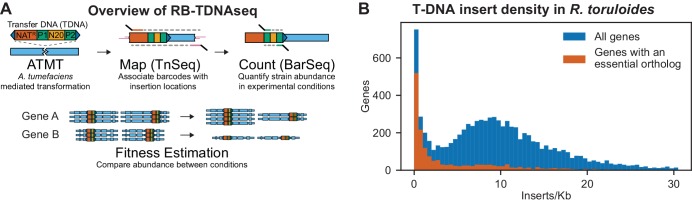

Figure 1. Overview of RB-TDNAseq and T-DNA insert density in R. toruloides coding regions.

(A) General strategy of RB-TDNAseq. A library of binary plasmids bearing an antibiotic resistance cassette (NATR) and a random 20 base-pair sequence ‘barcode’ (N20) flanked by specific priming sites (P1/P2) is introduced into a population of A. tumefaciens carrying a vir helper plasmid. A. tumefaciens efficiently transforms a T-DNA fragment into the target fungus (ATMT). NATR colonies are then combined to make a mutant pool. T-DNA-genome junctions are sequenced by TnSeq, thereby associating barcodes with the location of the insertion (Map). The mutant pool is then cultured under specific conditions and the relative abundance of mutant strains is measured by sequencing a short, specific, PCR on the barcodes (BarSeq) and counting the occurrence of each sequence (Count). Finally, for each gene, count data is combined across all barcodes mapping to insertions in that gene to obtain a robust measure of relative fitness for strains bearing mutations in that gene (Fitness Estimation). (B) Histogram of insert density in coding regions (start codon to stop codon) for all genes, and genes with orthologs reported to be essential in A. nidulans, C. neoformans, N. crassa, S. cerevisiae, or S. pombe. The following figure supplements are available for Figure 1.