Abstract

Importance

There is a deficit of pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide (PACAP) in patients with neuropathologically confirmed Alzheimer dementia. However, whether this deficit is associated with the earlier stages of Alzheimer disease (AD) is unknown. This study was conducted to clarify the association between PACAP biomarkers and preclinical, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia stages of AD in postmortem brain tissue.

Objectives

To examine PACAP and PACAP receptor levels in postmortem brain tissues and cerebrospinal fluid from cognitively and neuropathologically normal control individuals, patients with MCI due to AD (MCI-AD), and individuals with AD; analyze the relationship between PACAP, cognitive, and pathologic features; and propose a model to assess these relationships.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We measured PACAP and its receptor (PAC1) levels using enzyme-linked immunoassay. A total of 35 cases were included. All the brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid samples were selected from Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program. All cognitive test results were in record with the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium.

Main Outcomes and Measures

A comparison of PACAP and PAC1 levels among the healthy controls, MCI-AD, and AD dementia groups, as well as a systematic correlation analysis between PACAP level, cognitive performance, and pathologic severity.

Results

The PACAP levels in cerebrospinal fluid, the superior frontal gyrus, and the middle temporal gyrus were inversely related to dementia severity. The PACAP levels in cerebrospinal fluid correlated with the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score (Pearson r = 0.50; P = .03) and inversely correlated with total amyloid plaques (Pearson r = −0.48; P < .01) and tangles (Pearson r = −0.55; P = .01) in the brain. The PACAP in the superior frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus correlated with the Stroop Color-Word Interference Test (Pearson r = 0.58; P < .01) and the Auditory Verbal Learning Test–Total Learning (Pearson r = 0.33; P = .02), respectively. The PACAP in the primary visual cortex did not correlate with the Judgment of Line orientation test (P = .14). Furthermore, the PAC1 level in the superior frontal gyrus showed an upregulation in MCI-AD but not in AD. The pharmacodynamic model of the PACAP-PAC1 interaction best predicted cognitive function in the superior frontal gyrus, but it was less predictive in the middle temporal gyrus and failed to be predictive in the primary visual cortex.

Conclusions and Relevance

Deficits in PACAP are associated with clinical severity in the MCI and dementia stages of AD. Additional studies are needed to clarify the role of PACAP deficits in the predisposition to, pathogenesis of, and treatment of AD.

Introduction

Pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide (PACAP) was initially isolated from the ovine pituitary gland and characterized as a small peptide with either 38 amino acids in full-length form (PACAP-38) or 27 amino acids in short form (PACAP-27).1 Both forms strongly increase cyclic adenosine monophosphate by activating adenylate cyclase.2,3 Subsequent research2,3 showed that PACAP is not only an endocrine hormone but is also intrinsically expressed in multiple brain regions and peripheral tissues. PACAP is a potent neurotrophic and neuroprotective peptide in the central nervous system. PACAP-38 is the major form of PACAP in the brain. Both forms of PACAP bind to and activate G-protein–coupled receptors (PAC1, vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor [VPAC] type 1, and VPAC2). PAC1 is mainly localized in the central nervous system; VPAC1 and VPAC2 are found in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral system.

A deficit in PACAP was associated with the pathologic severity of Alzheimer disease (AD).4 A PACAP deficit was also seen in PS1/APPswe/tauP301L triple transgenic mice.5 Exogenous PACAP protects neurons from the toxicity of β-amyloid 42 oligomers, which is achieved through increasing sirtuin 3 expression, which in turn enhances mitochondrial function. However, whether this reduction precedes the onset of dementia is unknown. Since AD-related cognition declines progressively from cognitively normal (CN) to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and then to dementia, we investigated PACAP levels in postmortem brains in this continuous spectrum of cognitive decline. We also studied the relationship between region-specific PACAP levels and cognitive performance in each group. Furthermore, we quantified PAC1 in the same brain regions and constructed the ligand-receptor interaction pharmacodynamic model to predict cognitive function.

Methods

Approval for the study was provided by the Western Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent had been provided by the donors’ families. Deidentified postmortem human cerebral cortex and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were obtained from the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center and the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program, including 16 AD, 9 MCI-AD, and 10 CN cases. All AD cases were selected as being intermediate or high probability for AD according to National Institute on Aging–Reagan criteria (National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer Association criteria).6 The samples were free of other neurodegenerative disorders, such as vascular dementia, Parkinson disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia, hippocampal sclerosis, progressive supranuclear palsy, dementia lacking distinctive histologic features, multiple system atrophy, motor neuron disease with dementia, and corticobasal degeneration. Mild cognitive impairment was diagnosed by consensus as a syndrome of cognitive impairment beyond age-adjusted norms that is not severe enough to impair daily function or fulfill clinical criteria for dementia.7–10 To ensure MCI as an early stage of AD, we excluded 3 cases of MCI that did not have AD pathologic characteristics. All patients had undergone longitudinal clinical and neuropsychological assessment. Since PACAP levels may change with age, only the final antemortem assessment score within 1 year before death, if available, was included for PACAP correlation analysis. The raw scores from the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, Stroop Color-Word Interference Test, Auditory Verbal Learning Test–Total Learning (AVLT-TL), and Judgment of Line orientation (JLO), as well as the total number of words learned over trials (new learning) score, were converted to age- and education-corrected z scores.4

We measured samples from parenchymal cortical homogenate, including superior frontal gyrus (SFG), middle temporal gyrus (MTG), and primary visual cortex (PVC), and from CSF. Protein samples and CSF were quantified for PACAP and PAC1 using a standard enzyme-linked immunoassay kit (catalog No. MBS160511 and MBS042704, MyBiosource Inc) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, protein samples were loaded and incubated with biotin-labeled PACAP antibody or PAC1 antibody at 37°C for 60 minutes. The plate was washed with the washing buffer 5 times, followed by incubation with chromogen solution at 37°C for 10 minutes. The reaction was stopped by adding stop solution. The final results were read at wavelength 450 nm. In parallel, the protein quantity was determined with a Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (catalog No. 23227, Thermo Scientific,). To eliminate the confounding factor of potential neurodegeneration, we normalized the PACAP level to the protein level in the brain tissue. Therefore, PACAP in cortical tissues was expressed as nanograms per milligram of total protein, whereas PACAP in CSF was expressed as nanograms per milliliter of CSF.

We used analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey pairwise comparisons and Pearson product moment correlations, setting P < .05 as the level of significance. All results are presented as mean (SD) in the Table and mean (SE) in Figures 1, 2, and 3. We preselected particular cognitive tests to reflect the brain regions being studied, thus reducing the need for multiple comparison adjustments. We hypothesized that the PACAP-PAC1 interaction would produce a net biological effect that correlated with specific cognitive function. The ligand (L)–receptor (R) interaction pharmacodynamic model obeys the chemical kinetic principle.11 In the present study, L represents PACAP and R represents PAC1. We assumed that the biological activity (cognitive performance in our study) is determined by the interaction of n mole of PACAP with each mole of PAC1. Therefore, n(L) + (R) = (LnR), leading to biological activity. At equilibrium, Kd = (LnR)/(L)n (R), where Kd is the disassociation factor. Therefore, we hypothesized that the z score of cognitive performance is linearly proportional to (L)n (R). We conducted a series of linear correlation analyses between the product of (PACAP)n × (PAC1) and cognitive performance z scores.

Table.

Patient Demographic and Cognitive Data

| Characteristic | CN (n = 10) | MCI (n = 9) | AD (n = 16)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 8(80) | 4(44) | 7(44) |

| Female | 2(20) | 5(56) | 9(56) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 86.3 (5.7) | 87.2 (4.6) | 81.7(8.9) |

| Most recent antemortem cognitive task performance, mean (SD), z scorea | |||

| DRS | 0.95 (0.50) | −0.85 (0.81)b | −2.31 (0.65)b |

| Stroop Color-Word Interference Test | 0.38(1.05) | −0.83 (1.17) | −1.87 (1.11)b |

| AVLT-TL | 0.34 (0.96) | −1.15 (0.89)c | −2.58 (1.73)b |

| JLO | 1.33 (1.05) | 0.93 (0.84) | −1.03 (1.53)d |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; AVLT-TL, Auditory Verbal Learning Test–Total Learning; CN, cognitively normal; DRS, Dementia Rating Scale; JLO, Judgment of Line orientation test; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Cognitive testing was done within 1 year of death. All scores were converted to z scores based on age- and education-corrected norms.

P < .001 compared with the CN group using 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey analysis.

P = .01.

P< ..1

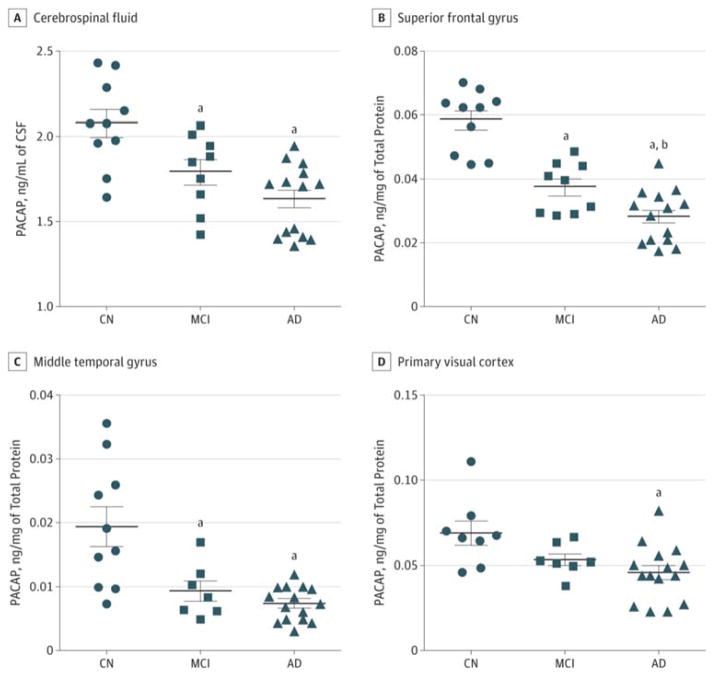

Figure 1. Comparison of Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase–Activating Polypeptide (PACAP) Abundance in Selected Cerebral Regions Among Cognitively Normal (CN), Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer Disease (AD) Individuals.

A, PACAP in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was significantly reduced in the MCI (P = .03) and the AD (P < .01) groups compared with the CN group. B, PACAP in the superior frontal gyrus (SFG) was significantly reduced in the MCI (P < .01) and AD (P < .001) groups compared with the CN group and in the AD group (P = .04) compared with the MCI group. C, PACAP in the middle temporal gyrus (MTG) was significantly reduced in the MCI and AD groups (both P < .001) compared with the CN group. D, PACAP in the primary visual cortex (PVC) was significantly reduced in the AD group (P = .04) compared with the CN group. Proteins were obtained from the same tissue sample of SFG, MTG, and PVC. Bars indicate means; limit lines, SEs. One-way analysis of variance with the post hoc Tukey test was used in the analysis.

aSignificant reduction vs the CN group.

bSignificant reduction vs the MCI group.

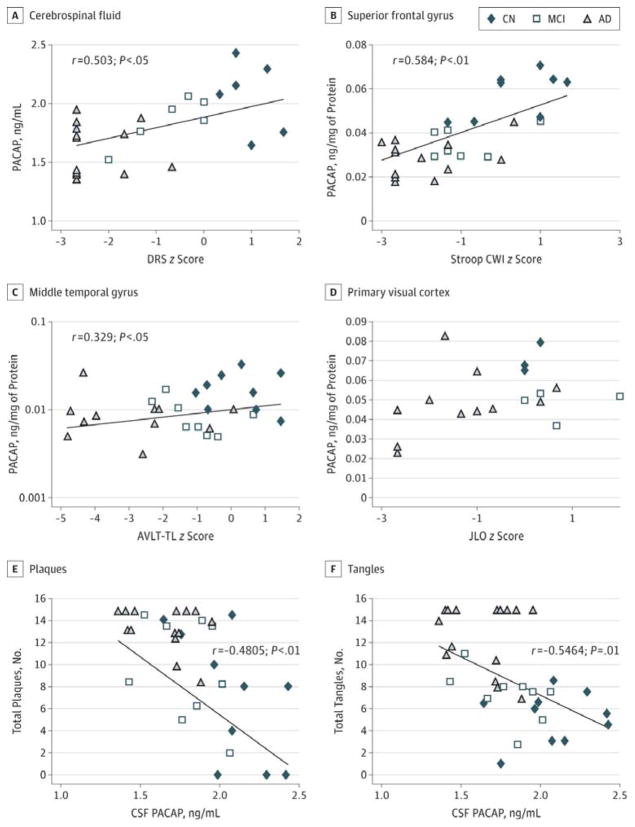

Figure 2. Correlation of Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase–Activating Polypeptide (PACAP) Levels in Different Brain Areas and Respective Cognitive Tests.

A through D, PACAP levels in selected cerebral regions correlated with region-specific cognitive tests. The y-axis in C is on a log scale to fit best with a linear model owing to the relatively large difference between middle temporal gyrus PACAP in CN and AD samples. E and F, PACAP in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inversely correlated with total amyloid plaque and total tangles. Solid fitted lines indicate significant Pearson correlations (A, P = .03; B, P = .02). AD indicates Alzheimer disease; AVLT-TL, Auditory Verbal Learning Test–Total Learning; CN, cognitively normal; CWI, Color-Word Interference; DRS, Dementia Rating Scale; JLO, Judgment of Line Orientation; and MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

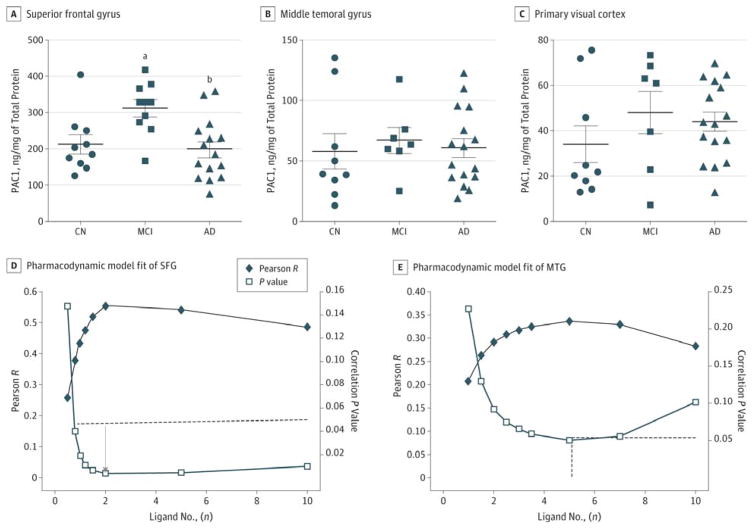

Figure 3. Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase–Activating Polypeptide (PACAP) Receptor (PAC1) in Selected Cerebral Regions and the PACAP-PAC1 Interaction.

A, PAC1 quantification in the superior frontal gyrus (SFG). B, PAC1 quantification in the middle temporal gyrus (MTG). C, PAC1 quantification in the primary visual cortex. D, Pharmacodynamic model fit of SFG PACAP and SFG PAC1 level to predict the correlation with Stroop Color-Word Interference Test z scores. The dashed line marks the point at significant correlation (P < .05); the arrow indicates the nadir point with the minimal P value. E, Pharmacodynamic model fit of MTG PACAP and MTG PAC1 levels to predict the correlation with Auditory Verbal Learning Test–Total Learning scores. The dashed line marks the point at significant correlation (P < .05). For A through C, bars indicate means; limit lines, SEs. AD indicates Alzheimer disease; CN, cognitively normal; and MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

aP = .02, determined using 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey tests, vs the CN group.

bP = .02, determined using 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey tests, vs the MCI group.

Results

Patient demographic data and final antemortem cognitive scores are summarized in the Table. There were 10 patients in the CN group, 9 in the MCI-AD group, and 16 in the AD group; the mean (SD) age was similar among the 3 groups. The PACAP levels in CSF were reduced in patients with AD compared with the CN individuals (1.61 [0.06] ng/mL vs 2.08 [0.08] ng/mL; P < .01). The PACAP levels in the patients with MCI-AD were also significantly reduced, albeit to a lesser extent (1.80 [0.07] ng/mL; P = .04) (Figure 1A). This progressive reduction of PACAP from CN to MCI-AD and then to AD was also apparent in SFG and MTG. The PACAP in SFG (Figure 1B) was reduced in patients with MCI-AD (3.77 [0.26] × 10−2 ng/mg; P < .01) and AD (2.85 [0.19] × 10−2 ng/mg; P < .001) compared with the CN individuals (5.87 [0.31] × 10−2 ng/mg). The PACAP in MTG (Figure 1C) in 8 patients (89%) with MCI-AD (0.95 [0.16] × 10−2 ng/mg; P < .001) and the AD group (0.75 [0.06] × 10−2 ng/mg; P < .01) was reduced compared with that of the CN individuals (1.95 [0.31] × 10−2 ng/mg). In PVC, PACAP (Figure 1D) was reduced in patients with AD (4.62 [0.39] × 10−2 ng/mg; P < .05) but not in 7 with MCI-AD (78%) (5.31 [0.36] × 10−2 ng/mg; P = .18) compared with 8 CN individuals (80%) (6.93 [0.71] × 10−2 ng/mg). Therefore, PACAP reduction is evident at the MCI-AD stage that precedes the onset of AD in the expected brain regions.

Since cognitive decline can occur in multiple cognitive domains, we analyzed the relationship between PACAP levels and cognitive performance. PACAP levels in CSF were correlated with Mattis Dementia Rating Scale z scores (Pearson r = 0.50; P = .03) (Figure 2A), suggesting that the reduction of aggregated PACAP levels in the central nervous system is correlated with poorer global cognitive function (per scores on the Dementia Rating Scale). Furthermore, PACAP levels in SFG were correlated with Stroop Color-Word Interference Test z scores (Pearson r = 0.58; P < .01) (Figure 2B), a task that is sensitive to frontal lobe function. The PACAP levels in the MTG correlated with the AVLT-TL z scores (Pearson r = 0.33; P = .02) (Figure 2C), a task that is sensitive to temporal lobe function. By contrast, PACAP levels in the PVC did not correlate with JLO scores (P = .14) (Figure 2D), a visuospatial task sensitive to occipitoparietal functioning. In addition, the CSF PACAP level inversely correlated with the total number of amyloid plaques (r = −0.48; P < .01) (Figure 2E) and total number of tangles (r = −0.55; P = .01) (Figure 2F).

Since PACAP exerts its physiologic function by binding to PAC1 receptors in the brain, we measured the quantity of PAC1 in the SFG, MTG, and PVC. Because PAC1 is located on the cell membrane, it is not detectable in CSF. In SFG, the PAC1 level in the AD group (199 [22] ng/mg) was not significantly different from that of the CN group (213 [25] ng/mg) (Figure 3A). The PAC1 level in MCI-AD (312 [25] ng/mg; P = .02) was higher than that in CN samples (Figure 3A). However, this PAC1 upregulation in MCI-AD was not observed in MTG or PVC. The PAC1 level in MTG was 58 (14) in CN (9 [90%]), 67 (10.4) in MCI-AD (8 [89%]), and 61 (7.9) in AD (16 [100%]) (P = .47) (Figure 3B). PAC1 in PVC was 34 (8.2) in CN (9 [90%]), 48 (9.5) in MCI-AD (8 [89%]), and 44 (4.2) in AD (16 [100%]) (P = .51) (Figure 3C). The relative abundance of PAC1 was SFG ≫ MTG > PVC and was not affected by the disease stages (ie, MCI-AD or AD).

According to the pharmacodynamic model, the interaction of ligand and receptor determines the biological activity. We hypothesized that the product of (PACAP)n × (PAC1R) would predict cognitive function. Based on the algorithms described in detail in the Methods section, a series of Pearson r and associated correlation P values were calculated by varying ligand numbers in the range of 0 to 10. The relationship between the Pearson r (or P value) and ligand number (n) was fit into a polynomial relationship. In the SFG, 2 PACAP molecules for each PAC1 was required to reach P < .05 (Figure 3D). This finding suggests that a ratio of PACAP to PAC1 at 2:1 best predicts the Stroop Color-Word Interference Test cognitive function in SFG. In MTG, more PACAP (≥5) was required to bind to PAC1 to reach significant correlation with AVLT-TL. In PVC, the P value nadir (P = .16) did not reach statistical significance regardless of the ligand number, suggesting that the PACAP-PAC1 interaction in the PVC did not predict JLO. Thus, the ligand-receptor interaction predicted regional cognitive function best in SFG, was less predictive in MTG, and failed to be predictive in PVC.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that PACAP levels start to decline before the onset of AD dementia as early as the MCI-AD stage. This reduction in PACAP is region specific, targeting vulnerable areas of the AD brain. Combined with previous studies,4 these data support the possibility that the PACAP deficit is a risk factor for AD pathogenesis. Furthermore, the PACAP deficit in selected cerebral regions may predict region-specific cognitive function deterioration. We have found the strongest correlation between PACAP levels and cognitive performance in SFG and MTG, 2 regions heavily involved in AD pathologic changes and both of which represent cognitive abilities that are affected early in the course of AD. The CSF PACAP level inversely correlates with the total quantities of amyloid plaques and tangles, a finding that is consistent with a previous pilot study.4 The PACAP-specific receptor PAC1 demonstrated a transient upregulation in the frontal lobe of patients with MCI-AD but not in those with AD, suggesting a potential compensatory mechanism in MCI-AD. Patients with AD may lose this compensatory capability as the disease progresses.

The ligand-receptor pharmacodynamic model predicts lower levels of PAC1 in MTG than in SFG. An alternative explanation is that a large proportion of measured PACAP in MTG is intracellularly retained and unavailable for paracrine secretion since our measurement did not discern multiple compartments in tissues, or there is another subtype of PAC1 that has a weak ligand-receptor interaction in this region. Taken together, the action target of PACAP is predominantly localized in the frontal lobe. This MTG-SFG pathway is consistent with the proposed neurodegenerative network most affected in AD.12

The PACAP level in SFG is higher than that of MTG in CN individuals and those with MCI-AD or AD. However, the PACAP deficit in AD is more severe in MTG (an approximately 60% reduction) than in SFG (45% reduction). The total β-amyloid in SFG was increased 10-fold in AD compared with the CN samples,13 whereas the total β-amyloid in MTG was increased 100-fold in AD.14 This regional difference in β-amyloid deposition is consistent with the inverse relationship between PACAP and amyloid load as shown in a pilot report4 and confirmed in the present study.

Although the human studies of PACAP are in the preliminary stage, animal studies have shown beneficial effects of PACAP on cognition and memory. The earliest clue of PACAP’s effects on memory came from amnesiac (amn) (GenBank AF461122.1) gene–mutant flies.15 The amn gene encodes a homologue of vertebral PACAP. PACAP is also essential for associative memory in Lymnaea stagnalis, a prototype model for studying the molecular mechanism of simple associative learning.16 Most importantly, intranasal administration of PACAP enhances novel object recognition in senescence-accelerated mouse-prone 8 mice17 and amyloid precursor protein–transgenic mice.18 The memory-enhancing effect of PACAP may be mediated by multiple molecular mechanisms, including enhancing inward currents through the N-methyl-d-aspartate channel19 and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid channel20 as well as inhibiting the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide–gated channel21 or A-type K channel.22,23

There are several limitations to the present study. First, this was a small cross-sectional study with sex imbalance among the groups. However, we found a clear demarcation of PACAP among CN, MCI-AD, and AD brain tissues. Second, although postmortem CSF is not as ideal as CSF from living persons, we used it in conjunction with neuropathologic diagnosis. Our brain bank (Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program) has studied postmortem CSF extensively and has obtained results similar to those of other groups4 who have used CSF from living individuals. Thus, postmortem CSF can be optimized as a medium for biomarker studies. It would be valuable to evaluate a larger sample of PACAP in CSF in living persons in a longitudinal study. Third, because this was a retrospective study using postmortem brain tissues, we cannot infer causality. Nevertheless, previous studies4,5,18 suggest biological plausibility and the potential mitochondrial target of PACAP. Additional studies are needed to clarify the role of PACAP in the predisposition to and pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of AD.

Conclusions

Deficits in PACAP are associated with clinical severity in the MCI and dementia stages of AD. This deficit may be an early event in the progression of Alzheimer dementia.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Funding was provided by the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium (National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging grant P30 AG19610 and the state of Arizona), the Barrow Neurological Foundation, and a joint translational neuroscience grant from the Barrow Neurological Institute and University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Footnotes

Additional Contributions: We are grateful for patients who donated their brains as well as for their families.

Author Contributions: Drs Shi and Han had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Han, Baxter, Reiman, Shi.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Han, Caselli, Serrano, Yin, Beach, Reiman, Shi.

Drafting of the manuscript: Han, Shi.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Han, Shi.

Obtained funding: Han, Beach, Reiman, Shi.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Han, Caselli, Serrano, Yin, Beach.

Study supervision: Han, Reiman.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Miyata A, Arimura A, Dahl RR, et al. Isolation of a novel 38 residue-hypothalamic polypeptide which stimulates adenylate cyclase in pituitary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;164(1):567–574. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61(3):283–357. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Yon L, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide and its receptors: from structure to functions. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52(2):269–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han P, Liang W, Baxter LC, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide is reduced in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2014;82(19):1724–1728. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han P, Tang Z, Yin J, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide protects against β-amyloid toxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(9):2064–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56(10):1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Imaging and biomarkers in early Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(4):438–441. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen RC. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: is MCI too late? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(4):324–330. doi: 10.2174/156720509788929237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. MRI and CSF biomarkers in normal, MCI, and AD subjects: predicting future clinical change. Neurology. 2009;73(4):294–301. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181af79fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. MRI and CSF biomarkers in normal, MCI, and AD subjects: diagnostic discrimination and cognitive correlations. Neurology. 2009;73(4):287–293. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181af79e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson SW. The Foundations of Chemical Kinetics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filippi M, Agosta F. Structural and functional network connectivity breakdown in Alzheimer’s disease studied with magnetic resonance imaging techniques. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(3):455–474. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, et al. Soluble amyloid β peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(3):853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Lindholm K, Yang LB, et al. Amyloid β peptide load is correlated with increased β-secretase activity in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(10):3632–3637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0205689101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feany MB, Quinn WG. A neuropeptide gene defined by the Drosophila memory mutant amnesiac. Science. 1995;268(5212):869–873. doi: 10.1126/science.7754370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirger Z, Laszlo Z, Hiripi L, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) and its receptors are present and biochemically active in the central nervous system of the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;42(3):464–471. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonaka N, Farr SA, Nakamachi T, et al. Intranasal administration of PACAP: uptake by brain and regional brain targeting with cyclodextrins. Peptides. 2012;36(2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rat D, Schmitt U, Tippmann F, et al. Neuropeptide pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide (PACAP) slows down Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in amyloid precursor protein–transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2011;25(9):3208–3218. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-180133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macdonald DS, Weerapura M, Beazely MA, et al. Modulation of NMDA receptors by pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide in CA1 neurons requires Gαq, protein kinase C, and activation of Src. J Neurosci. 2005;25(49):11374–11384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3871-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel S, Itri J, Han JH, Gniotczynski K, Colwell CS. Regulation of glutamatergic signalling by PACAP in the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He C, Chen F, Li B, Hu Z. Neurophysiology of HCN channels: from cellular functions to multiple regulations. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;112:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han P, Lucero MT. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide reduces A-type K+ currents and caspase activity in cultured adult mouse olfactory neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;134(3):745–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han P, Lucero MT. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide reduces expression of Kv1.4 and Kv4.2 subunits underlying A-type K+ current in adult mouse olfactory neuroepithelia. Neuroscience. 2006;138(2):411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]