Abstract.

Although acute diarrheal deaths have declined globally among children < 5 years, it may still contribute to childhood mortality as an underlying or contributing cause. The aim of this project was to estimate the incidence of acute diarrhea-associated deaths, regardless of primary cause, among children < 5 years in Bangladesh during 2010–12. We conducted a survey in 20 unions (administrative units) within the catchment areas of 10 tertiary hospitals in Bangladesh. Through social networks, our field team identified households where children < 5 years were reported to have died during 2010–12. Trained data collectors interviewed caregivers of the deceased children and recorded illness symptoms, health care seeking, and other information using an abbreviated international verbal autopsy questionnaire. We classified the deceased based upon the presence of diarrhea before death. We identified 880 deaths, of which 36 (4%) died after the development of acute diarrhea, 17 (2%) had diarrhea-only in the illness preceding death, and 19 (53%) had cough or difficulty breathing in addition to diarrhea. The estimated annual incidence of all-cause mortality in the unions < 13.6 km of the tertiary hospitals was 26 (95% confidence interval [CI] 16–37) per 1,000 live births compared with the mortality rate of 37 (95% CI 26–49) per 1,000 live births in the unions located ≥ 13.6 km. Diarrhea contributes to childhood death at a higher proportion than when considering it only as the sole underlying cause of death. These data support the use of interventions aimed at preventing acute diarrhea, especially available vaccinations for common etiologies, such as rotavirus.

INTRODUCTION

Deaths due to diarrhea among children have declined worldwide. An estimated 4.6 million deaths among children < 5 years per year were attributed to diarrhea in 1982.1 In 1990, this estimate declined to 2.5 million deaths annually2 and further declined with an estimated 0.5 million in 2013.3 The international network for demographic surveillance of population and their health in developing countries (INDEPTH) network reported across 18 sites in Africa and Asia during 2006–2012 that diarrhea was no longer among the leading causes of death among children aged < 5 years.4 However, the INDEPTH estimated substantial diarrheal deaths among children aged 1–4 years during 2006–2012 in Bangladesh (18% of deaths identified in four sites), Ghana (25% of deaths identified in two sites), Kenya (17% of deaths identified in two sites), and South Africa (20% of deaths identified in two sites).4

The most recent estimate of the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS), conducted in 2011, reported 2% of deaths among children < 5 years were due to diarrhea.5 This represented a reduction from the 2004 estimate of 5% of deaths due to diarrhea among children < 5 years in Bangladesh.6 Although diarrhea may no longer be a leading cause of death, it may still contribute to childhood mortality as an underlying or contributing cause. The WHO defines the “underlying cause of death” as the disease or injury that initiated the chain of morbid events which directly led to death.7 Thus, a condition may be deemed as “contributing” without needing to be identified as the direct or underlying cause of death. The contribution of diarrhea to childhood deaths may not be apparent from mortality estimates that only consider a single cause of death.8 If diarrhea remains a contributing or underlying cause of death, investments in reducing the incidence of diarrhea may still be valuable in reducing child deaths. Studies that report only one primary cause of death are insufficient to determine the potential public health value of diarrhea prevention for reducing mortality.

The objective of this study was to estimate the incidence of acute diarrhea-associated deaths, regardless of primary cause, among children < 5 years in Bangladesh during 2010–12.

METHODS

Data collection.

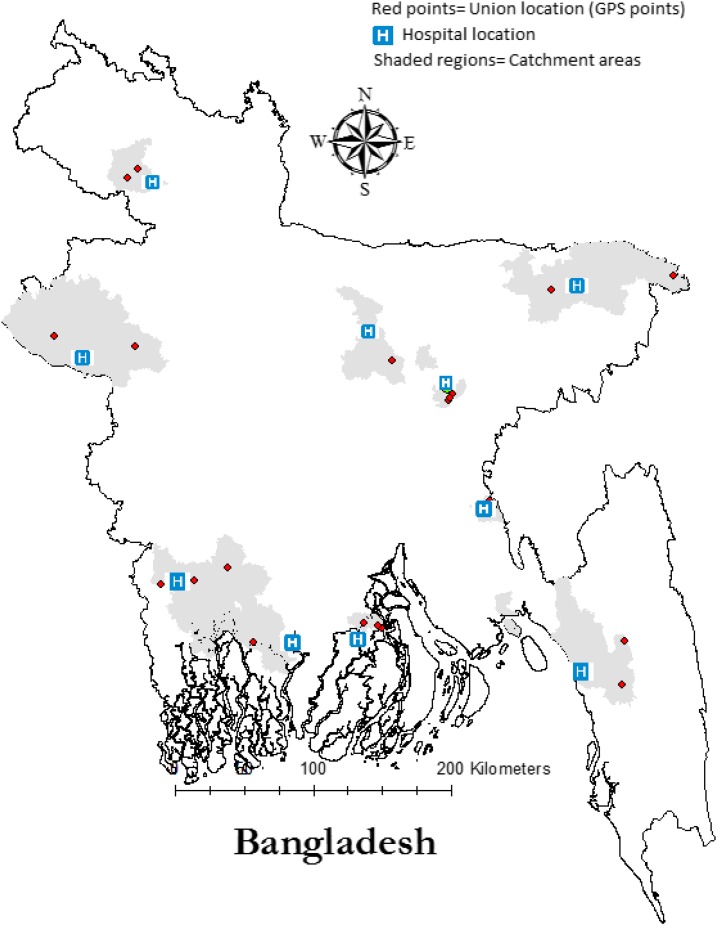

Our study was carried out in the catchment areas of 10 tertiary care hospitals used for infectious disease surveillance, located throughout the country (Figure 1). To define the catchment area for each hospital, we reviewed the logbooks to identify the subdistricts where at least 75% of all pediatric patients hospitalized in 2010–11 resided. We randomly selected two global positioning system (GPS) coordinates in each hospital catchment area (Figure 1). The unions (small administrative units with an average population of 24,000) where these GPS points were located were included in the population-based survey. We contacted officials in each union to obtain a list of the villages in their unions. The field data collection team visited each village in each of the 20 unions during July to December 2012 to identify deaths that had occurred among children < 5 years in each community during May 2010 to April 2012.

Figure 1.

Locations of 10 sentinel hospitals, the catchment areas of these hospitals and the 20 study unions in Bangladesh, 2010–12. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

We assumed 2% deaths among our population of interest.5 With 5% significance, we selected a precision of 1% around our estimated proportions. We needed to have a population sample size of 142,668 after accounting for a design effect of 2.0.9 To achieve the required sample size, we conducted our survey in 20 unions.

We used a social-networking approach to identify child deaths.10,11 The field team interviewed people at key social gathering points of the villages, such as the community centers, tea stalls and bazaars and asked if they knew of any deaths of children in the villages in the specified timeframe. They also interviewed women at courtyard gatherings and men at mosques. The field team compiled a list of homesteads for each village in which at least one child was reported to have died. If a family member of the deceased child confirmed the death within our specified timeframe and that the age of the child was < 5 years at the time of death (including death in the neonatal period, i.e., under 1 month of age), the field team enrolled the household in the study and obtained information through a standardized questionnaire. If the reported death was due to injury, the team visited the houses to confirm date of death and age of the deceased but did not administer the questionnaire. In all noninjury-related deaths, the data collectors visited each of the homesteads, recoded illness information, and health seeking during illness. The field team used an abbreviated international verbal autopsy questionnaire of the WHO, version 201212 to collect information about the death. We omitted sections on “data abstracted from death certificate” and “data abstracted from other health record” from the WHO questionnaire as it is not common in rural Bangladesh to have this information available. Parents of the deceased children, or those who had provided supportive care to the decedents during illness, were asked to recall symptoms, health-seeking during the illness, such as whether the child was admitted to a hospital or seen by a physician, and information on monthly household expenses as a proxy measure for income. We also collected the GPS coordinates of the enrolled households to measure the distance from the nearest tertiary care hospitals. We obtained written informed consent from the head of the households before administering questionnaires. The protocol was approved by icddr,b’s Ethics Review Committee.

Classifying deaths.

We defined acute diarrhea-associated death as deaths among children who experienced sudden onset of loose, watery stools for three or more times in 24 hours for at least 2 days within 14 days of death and who died in the same illness episode, regardless of other signs and symptoms of illness. We classified the deaths as acute diarrhea-only if diarrhea with or without vomiting, but no other symptoms were present before death.

Data analysis.

We used 2011 census data to estimate the total number of children < 5 years living in the study unions13 and the proportion of the total population of Bangladesh that live within these unions. Assuming the population to live birth ratio for Bangladesh of 4.0,14 we estimated the annual live births in the 20 unions to calculate acute diarrhea-associated mortality per 1,000 live births. This ensured comparability of our rates with BDHS estimates. We used the following equation to calculate the incidence of mortality:

where,

I = Incidence of acute diarrhea-associated deaths among children < 5 years per 1,000 live births annually.

D = Number of acute diarrhea-associated deaths among children < 5 years in the community in 2010–12.

P = Estimated annual live births in the 20 unions from census data.

Because the deaths took place over a duration of 2 years, we divided the death estimates by two to get an annual average estimate. To calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the incidence estimates, we assumed the variance of deaths assuming Poisson distribution.15 We calculated the proportion of acute diarrhea-associated deaths where cough or difficulty breathing was also reported as part of the illness by the caregiver.

To identify if deaths among children were different in unions located closer to the tertiary care facility or not, we calculated the median distance of our sampled unions from their nearest tertiary care hospital using the GPS coordinates that the field team collected. We calculated the average annual incidence of mortality rate for unions located within the median distance and farther than the median distance.

RESULTS

We identified a total of 894 deaths in the preceding 2 years among children aged < 5 years for all causes through social networking in the communities. We were able to locate all households where the children who reportedly died had lived. Eight hundred and eighty (98%) children were included in the analysis; 14 child deaths were excluded because their families refused to participate in the study. Of the 880 deceased, 121 (13.5%) were due to injury. Among the 880 children, 36 (4%; [95% CI 3–5%]) died after the development of acute diarrhea. Of these 36 children, 31 (86%) were aged < 2 years; 23 (64%) were infants. Seventeen (2%; [95% CI 1–3%]) children had diarrhea-only in the illness preceding death. We identified four acute diarrhea-associated deaths among neonates (< 1 month old). The median age at death for the children was 9.5 (interquartile range [IQR] 6–24) months. Nineteen (53%) were male (Table 1). Twenty-six (72%) children died within 7 days of onset of acute diarrhea.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children aged < 5 years who died (N = 36) with acute diarrhea in 20 unions in Bangladesh, 2010–12

| Characteristics | Acute diarrhea, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (in months) | 9.5 (IQR 6–24) |

| Female | 17 (47) |

| Highest level of treatment sought for diarrhea: | |

| At home (with oral rehydration solution) | 3 (8) |

| Unqualified doctor or pharmacy | 11 (31) |

| Hospitalization | 22 (61) |

| Symptoms present before death: | |

| Diarrhea | 36 (100) |

| Vomiting | 20 (55) |

| Fever | 18 (50) |

| Difficulty breathing | 17 (47) |

| Cough | 11 (30) |

| Died at home | 18 (50) |

| Household cumulative monthly expenses < US$100 | 34 (94) |

| Median distance of household from catchment hospitals (km) | 13.6 (IQR 5.4–26.7) |

IQR = interquartile range.

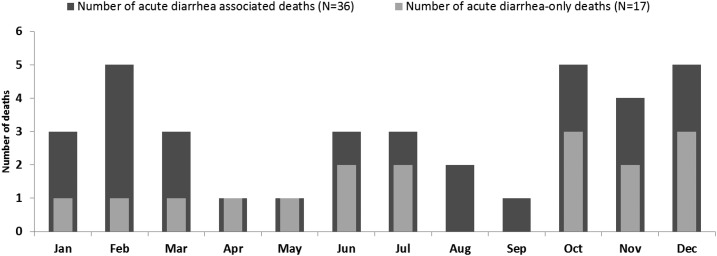

Among the 36 acute diarrhea-associated deaths, 19 (53%) had cough or difficulty breathing as part of the illness episode preceding death. Twenty (55%) had vomiting and 18 (50%) had fever. Among children who died with cough or difficulty breathing, 24% also had diarrhea as part of the illness episode before death. Seventeen of 36 acute diarrhea-associated deaths (47%) took place during November to February (Figure 2). All 36 children who died with diarrhea received oral rehydration solution at home during the illness; 22 (65%) were admitted to hospital at some point during their illness, and 11 (31%) received informal care either from unqualified doctors or drug sellers. Eighteen (50%) children died at hospitals. Four (11%) children who were hospitalized died at home; family members reported that they were unable to continue treatment at the hospital for economic reasons.

Figure 2.

Number of acute diarrhea-associated deaths (N = 36) and acute diarrhea-only (N = 17) deaths among children < 5 years in 20 unions in Bangladesh, 2010–2012.

We estimated an annual all-cause under-five mortality rate of 34 (95% CI 27–41) per 1,000 live births in the study unions. The median distance of the unions from the nearest tertiary care hospital was 13.6 km (IQR 5.4–26.7 km). For unions that were within the 13.6-km distance, we observed 437 (49%) all-cause deaths among children < 5 years. The estimated annual incidence of all-cause mortality in these unions (< 13.6 km) was 26 (95% CI 16–36) per 1,000 live births compared with the mortality rate of 37 (95% CI 25–49) per 1,000 live births in the unions located ≥ 13.6 km (P value for the χ2 test of homogeneity < 0.01). The acute diarrhea-associated mortality rate in the unions within 13.6 km was 2.1 (95% CI 1–10) per 1,000 live births compared with the annual rate of 2.9 (95% CI 1–11) per 1,000 live birth in the unions located ≥ 13.6 km (P = 0.35) (Table 2). The annual rate of hospitalizations in unions within 13.6 km of a tertiary care facility was six (95% CI 3–19) per 1,000 children < 5 years, compared with four (95% CI 1–13) hospitalizations per 1,000 children < 5 years in the unions located ≥ 13.6 km from a tertiary hospital (P value < 0.01).

Table 2.

Comparisons of children < 5 years who died in the unions located within 13.6 km of the nearest tertiary hospital with those who lived ≥ 13.6 km from the nearest tertiary hospital in Bangladesh, 2010–12

| Distance from surveillance hospitals* | Census population of children < 5 years (n) | All-cause deaths, N = 894, (%) | Acute diarrhea-associated deaths, N = 36, (%) | Incidence of all-cause mortality per 1,000 live births per year (95% CI) | Incidence of acute diarrhea-associated mortality per 1,000 live births per year (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 13.6 kilometers | 33,534 | 437 (49) | 18 (50) | 26 (16–36) | 2.1 (1–10) |

| ≥ 13.6 kilometers | 24,709 | 457 (51) | 18 (50) | 37 (25–49) | 2.9 (1–11) |

| P value† | – | – | – | < 0.01 | 0.35 |

CI = confidence interval.

Median distance threshold.

For χ2 test of homogeneity.

DISCUSSION

We estimated that 4% (95% CI 3–5%) of all childhood deaths among children < 5 years were associated with acute diarrhea in 20 unions in Bangladesh during 2010–12. About half of the children who had a diarrhea-associated death, also had either cough or difficulty breathing in addition to diarrhea. Most (86%) of the children who died were aged less than 2 years. We estimated that 2% (95% CI 1–3%) of death among children < 5 years were attributable acute diarrhea only, which was consistent with the 2011 BDHS estimate of the mortality fraction due to diarrhea among children < 5 years. BDHS used verbal autopsy to collect data for the deceased and reported one cause of death.16 In contrast to the BDHS, we did not attribute a single cause—rather we focused on the presence of diarrhea before death and identified diarrhea as a contributing cause. Although diarrheal deaths continue to decline among children, our study suggests that diarrhea still contributes to child deaths, and in a greater way than was previously appreciated. These findings underscore the importance of mortality studies that take into account the fact that child deaths often have more than one cause.

We identified a significantly higher incidence of all-cause of mortality rate in the unions that were ≥ 13.6 km from the tertiary care hospitals compared with unions that were closer to the hospitals. Children were less likely to be hospitalized if they resided in a union ≥ 13.6 km from the nearest tertiary care hospital. Distance to health care facility has been previously described as a traditional measure of access to care.17–19 In rural Niger, children < 5 years living close to the health dispensaries were 32% less likely to have died.17 Similarly, the odds of death was 33% (odds ratio 1.33; 95% CI 1.1–1.6) higher among infants who lived > 10 km from a health center compared with infants who lived within 10 km in rural Burkina Faso.18 In South Africa, respondents who lived farther than 5 km from the nearest facility were 16% less likely to report a recent health consultation.20 Our findings are consistent with another study in Bangladesh that distance from health care facility is a major barrier for seeking care, even for severe illnesses.21 These findings suggested that basic improvement in transportation infrastructure could reduce child mortality in rural Bangladesh.

Our estimated all-cause under-five mortality of 34 (95% CI 27–41) per 1,000 live births is below the national under-five mortality of 46 deaths per 1,000 live births.22 It is possible that under-five deaths were lower within the hospital catchment areas compared with the entire population because of better access to care by those served by the facilities. Another plausible explanation of the lower estimated mortality in our study unions is that we were not able to capture all deaths that may have occurred in the community, particularly those deaths occurring in the first few days of life, exemplified by only four acute diarrhea-associated neonatal deaths that were identified in this study. The BDHS data collectors visited each household in their designated area and interviewed respondents regarding information in the preceding 2 weeks. In contrast, we used social networking approach that was rapid and did not involve visiting each household in our sampled unions. Thus, our acute diarrhea-associated death estimate could be an underestimation of the true burden. However, this approach was substantially cost-effective and produced diarrheal death estimates that are comparable to national estimates. In a resource-limited setting, this approach could be a valuable methodology that can be expanded to more sites.

Viral gastroenteritis is the most common cause of diarrhea among children less than 5 years of age and rotavirus is among the most common etiology, along with norovirus GII strain and astrovirus.23 For countries like Bangladesh whose expanded program for immunization does not include rotavirus vaccine, the highest burden of diarrheal disease was attributed to rotavirus.23 In the current study, about half of the acute diarrhea-associated deaths took place during October to February, which is the peak rotavirus circulation period in the Bangladesh.24,25 In seven sentinel sites where hospital-based rotavirus surveillance was conducted during 2012–2015 in Bangladesh, similar pattern of higher hospitalizations due to acute gastroenteritis among children < 5 years was observed during November to February.26 It is possible that rotavirus contributed to some of these deaths that we identified in the community. Consequently, introducing rotavirus vaccine in Bangladesh could prevent acute diarrheal episodes and reduce the contribution of diarrhea in childhood deaths. Although the rotavirus vaccine is not as effective in Bangladesh as compared with the high-income countries, it still prevented 41% of illnesses27 which could substantially reduce the burden of diarrhea in Bangladesh.

Ascertaining cause of death and attributing a single cause of death among children is a conceptual over-simplification as comorbidity often occurs and many circumstances contribute to child deaths.28,29 A single cause of death analysis overlooks the fact that if competing causes are identified, interventions could be aimed at only one of the contributing causes and may still be sufficient to save a child.30 From a policy stand point, especially for a resource-poor setting, it is important to recognize that we may not have meaningful interventions for all possible etiologies. Availability of a practical intervention that has the potential to reduce the burden of a disease, regardless of if the disease is a sole cause of death or a comorbidity, is crucial. Diarrhea is not independent and is best considered as one of the contributing causes of childhood death and the value of reducing the disease should be recognized. Deaths from co-occurrence of diarrhea and pneumonia among children are 8.7 times more than if either of the disease acted alone.31 The synergistic comorbidity implies that if burden of one of the contributing causes can be reduced, there would be fewer children at risk of death from the other causes.

In a previous analysis of the BDHS data, acute respiratory infection (ARI) in combination with some form of diarrhea was accounted for 13% of all childhood deaths among children < 5 years in Bangladesh.32 In their attempt to describe the trends in childhood death in Bangladesh during 1993–2004, Liu et al.33 reallocated the deaths to either diarrhea or ARI where comorbidity of these two conditions was present to ensure comparability with previous estimates. The Guatemalan survey of family health also reported that among those children who had at least one respiratory symptom 2 weeks before the survey, 42% also had at least one coexisting gastrointestinal symptom.34 In our investigation, about half of the deceased children had at least one respiratory symptom, indicating that diarrhea and ARI may contribute to deaths in cases where either of these two were reported as the direct cause of death. Therefore, preventing diarrhea could prevent more deaths than the estimated 2% diarrhea-specific deaths.

Our study has some limitations. Because the respondents in our study had a recall period of 2 years for the illness symptoms, it is possible that they were not able to recall symptoms accurately. Although diarrhea is easily recognized by lay persons, it is possible that mild diarrheal episodes may not have been noticed or recalled. However, more severe diarrheal illness is more likely to contribute to death than milder illness, so we likely captured the most relevant episodes. Also, it is possible that respondents may have reported diarrheal episodes as associated with the illness before death, even though they occurred in previous illnesses, not directly related to the death. In these instances, the burden of diarrhea may be overestimated. However, our case definition required diarrheal episodes to be of sudden onset and not a continuation of previous illnesses and we likely were able to include episodes that were closely connected to death. Our methods likely missed deaths as evidenced by the low number of deaths that we identified among neonates. This has most likely resulted in an underestimation of the burden of acute diarrhea among this group. In addition, we were not able to measure the nutritional status of the deceased children, limiting our ability to comment on malnutrition as a contributor to these deaths. Malnutrition is prevalent among children < 5 years in Bangladesh35; it is associated with diarrhea and pneumonia36 and thus, we assume did contribute to many of these deaths.

Diarrhea contributes to childhood death at a higher proportion than when considering it only as the sole underlying cause of death. The introduction of rotavirus vaccine in Bangladesh would be expected to reduce the burden of the disease. This methodology can be a rapid and substantially cost-effective alternative to the laborious house-to-house survey, although special consideration should be given to neonatal deaths. Other low-income countries where vital registration coverage is poor could use similar approach to monitor contributing causes of death among under-five children.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Snyder JD, Merson MH, 1982. The magnitude of the global problem of acute diarrhoeal disease: a review of active surveillance data. Bull World Health Organ 60: 605–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL, 2003. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ 81: 197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, Cousens S, Mathers C, Black RE, 2015. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 385: 430–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streatfield PK, et al. 2014. Cause-specific childhood mortality in Africa and Asia: evidence from INDEPTH health and demographic surveillance system sites. Glob Health Action 7: 25363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and ICF International , 2013. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, MD: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International.

- 6.National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and ORC Macro , 2005. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Dhaka, Bangladesh: National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and ORC Macro.

- 7.WHO , 2015. Mortality Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/mortality/en/. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- 8.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, 2005. Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. Am J Public Health 95 Suppl 1: S144–S150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning , 2012. Population and Housing Census 2011. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

- 10.Homaira N, et al. 2012. Influenza-associated mortality in 2009 in four sentinel sites in Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ 90: 272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul RC, et al. 2011. A novel low-cost approach to estimate the incidence of Japanese encephalitis in the catchment area of three hospitals in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85: 379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO , 2012. Verbal Autopsy Standards: Ascertaining and Attributing Causes of Death. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Government of Bangladesh B , 2013. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Available at: http://www.bbs.gov.bd/Census.aspx?MenuKey=89. Accessed February 4, 2017.

- 14.Centre for Population UaCCC , icddr b , 2012. Health and Demographic Surveillance System. icddr b, ed. Health and Demographic Surveillance System- Matlab. Dhaka, Bangladesh: icddr,b. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckland ST, 1984. Monte Carlo confidence intervals. Biometrics 40: 811–817. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO , 2012. Verbal Autopsy Standards: The 2012 WHO Verbal Autopsy Instrument. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- 17.Magnani RJ, Rice JC, Mock NB, Abdoh AA, Mercer DM, Tankari K, 1996. The impact of primary health care services on under-five mortality in rural Niger. Int J Epidemiol 25: 568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becher H, Müller O, Jahn A, Gbangou A, Kynast-Wolf G, Kouyaté B, 2004. Risk factors of infant and child mortality in rural Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ 82: 265–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van den Broeck J, Eeckels R, Massa G, 1996. Maternal determinants of child survival in a rural African community. Int J Epidemiol 25: 998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaren ZM, Ardington C, Leibbrandt M, 2014. Distance decay and persistent health care disparities in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolay B, et al. 2017. Evaluating hospital-based surveillance for outbreak detection in Bangladesh: analysis of healthcare utilization data. PLoS Med 14: e1002218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute of Population Research and Training MA ; ICF International , 2016. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survery, 2014. Dhaka, Bangladesh: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platts-Mills JA, et al. 2015. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob Health 3: e564–e575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fun BN, et al. 1991. Rotavirus-associated diarrhea in rural Bangladesh: two-year study of incidence and serotype distribution. J Clin Microbiol 29: 1359–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaman K, et al. 2009. Surveillance of rotavirus in a rural diarrhoea treatment centre in Bangladesh, 2000–2006. Vaccine 27 Suppl 5: F31–F34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satter SM, Gastanaduy PA, Islam K, Rahman M, Rahman M, Luby SP, Heffelfinger JD, Parashar UD, Gurley ES, 2017. Hospital-based surveillance for Rotavirus gastroenteritis among young children in Bangladesh: defining the potential impact of a Rotavirus vaccine program. Pediatr Infect Dis J 36: 168–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaman K, et al. 2017. Effectiveness of a live oral human rotavirus vaccine after programmatic introduction in Bangladesh: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS Med 14: e1002282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudan I, et al. 2005. Gaps in policy-relevant information on burden of disease in children: a systematic review. Lancet 365: 2031–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulholland K, 2003. Global burden of acute respiratory infections in children: implications for interventions. Pediatr Pulmonol 36: 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith KR, Corvalan CF, Kjellstrom T, 1999. How much global ill health is attributable to environmental factors? Epidemiology 10: 573–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J, 2003. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet 361: 2226–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baqui AH, Black RE, Arifeen S, Hill K, Mitra S, al Sabir A, 1998. Causes of childhood deaths in Bangladesh: results of a nationwide verbal autopsy study. Bull World Health Organ 76: 161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Li Q, Lee RA, Friberg IK, Perin J, Walker N, Black RE, 2011. Trends in causes of death among children under 5 in Bangladesh, 1993–2004: an exercise applying a standardized computer algorithm to assign causes of death using verbal autopsy data. Popul Health Metr 9: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman N, Pebley AR, Gragnolati M, 2002. Choices about treatment for ARI and diarrhea in rural Guatemala. Soc Sci Med 55: 1693–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das S, Gulshan J, 2017. Different forms of malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh: a cross sectional study on prevalence and determinants. BMC Nutrition 3: 1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munthali T, Jacobs C, Sitali L, Dambe R, Michelo C, 2015. Mortality and morbidity patterns in under-five children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Zambia: a five-year retrospective review of hospital-based records (2009–2013). Arch Public Health 73: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]