Abstract

The current work investigates the notion that inducible clustering of signaling mediators of the IKK pathway is important for platelet activation. Thus, while the CARMA1, Bcl10, and MALT1 (CBM) complex is essential for triggering IKK/NF-κB activation upon platelet stimulation, the signals that elicit its formation and downstream effector activation remain elusive. We demonstrate herein that IKKβ is involved in membrane fusion, and serves as a critical protein kinase required for initial formation and the regulation of the CARMA1/MALT1/Bcl10/CBM complex in platelets. We also show that IKKβ regulates these processes via modulation of phosphorylation of Bcl10 and IKKγ polyubiquitination.

Collectively, our data demonstrate that IKKβ regulates membrane fusion and the remodeling of the CBM complex formation.

Keywords: IKKβ, SNARE machinery, CBM complex, ubiquitination

1. Introduction

Platelets play a very important role in inflammation and thrombosis [1]. Hyperactive platelets stimulate thrombus formation in response to rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, thereby promoting coronary artery disease such as myocardial infarction etc [2]. Several physiological agonists such as thrombin, arachidonic acid, and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) are involved in platelet activation [3–5]. This leads to the assembly of signaling mediators, lipid rafts, as well as the activation of several downstream signaling pathways that ultimately induce the activation of NFκB[6]. The IKK complex consists of two catalytic subunits (IKKα and IKKβ) and a regulatory subunit (IKKγ).

The IκB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB signaling pathway was first documented by us and others as an essential player in platelet activation [6, 7]. Moreover, IKKβ, in response to platelet activation, phosphorylates SNAP-23 resulting in enhanced Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor Attachment Protein REceptor (SNARE) complex formation, membrane fusion and granule release [6]. Also, inhibition of IKKβ blocked SNAP-23 phosphorylation and platelet secretion. Therefore, given the critical regulatory role IKKβ plays in these processes, delineating upstream pathways that control IKK activation are critical for an understanding the mechanisms that govern platelet activation.

In T-cells, the physical interaction between CARMA1/Bcl10 and Bcl10/MALT1 and CARMA1/MALT1 proteins- upon T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) ligation- initiates signals that control nuclear events, such as induction of immediate early response genes [8–11]. Moreover, CARMA1, which is a membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) protein, acts as a molecular scaffold, ultimately regulating the immunological synapse [11–13]. It has also been shown that the central linker domain of CARMA1 is phosphorylated by PKCα or PKCβ after lymphocyte activation [14–18]. This phosphorylation event seems to control the assembly of the CBM complex, i.e., association of CARMA1 with Bcl10/MALT1 [18]. Additionally, Bcl10 was found to be highly phosphorylated upon lymphocyte activation [19], which is dependent on the presence of CARMA1 [20], and can be induced by its overexpression or by PKCα [9, 11, 15]. However, nothing is known regarding how these signaling events take place in platelets.

The current studies present evidence that the inducible clustering of signaling mediators of the IKKβ pathways and the formation of higher-order multi-protein complexes is important for platelet activation. While we have previously shown that the CBM complex is essential for triggering IKK/NF-κB activation in platelets, the signals that elicit CBM complex formation and downstream effector activation remain elusive. Using a host of biochemical and genetic (PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox) approaches, we demonstrate that IKKβ is a critical protein kinase required for initial formation and- through phosphorylation of Bcl10 and IKKγ polyubiquitination- is involved in the regulation of the CBM complex. We also observed defects in membrane fusion in platelets from the IKKβ deletion mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and materials

Thrombin was from Chrono-Log (Havertown, PA). TRAP1 was from Peptides International (Louisville, KY). Phorbol 12-myristate 13 acetate was from Sigma-Aldrich. Rottlerin and Gö6976 was from Biomol (Plymouth, PA). A23187 and RO-31-8220 were from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN). Bcl10 inhibitor from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibody against pSer/Thr/Tyr was from ENZO Life Sciences, Inc. NY. Antibodies against TAK1/TAB2/CARMA1/MALT1/TRAF6/Bcl10/pBcl10 were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA), whereas IKKα/IKKβ/pIKKβ/IKKγ/pERK were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Mice and genotyping

Platelet factor 4 (PF4)-Cre+ [21] and IKK-βflox/flox mice [22] were genotyped and housed as described in Karim et al., [6].

2.3. Preparation of platelets

2.4. Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was carried out as described in Karim et al., [6, 23].

2.5. Immunoblotting

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy

Briefly, mouse platelets were isolated and stimulated with 0.1 U/mL of thrombin for 3 min. The platelets were then processed for electron microscopy as we described before [6, 24].

2.7. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times, and analysis of the data, using t-test, was performed using GraphPad PRISM statistical software (San Diego, CA), and presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was accepted at P<0.05 (two-tailed P value).

3. Results

3.1. Membrane fusion is defective in PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox mice

As part of the platelet secretion process, vesicles dock to the cell membrane and form heteromeric membrane protein complexes (such as SNARE), which is followed by fusion between the vesicular membrane and the plasma membrane [25]. The route of membrane fusion and the role of IKKβ in this process is unknown. Moreover, in earlier studies Karim et al. [6] showed that IKKβ regulates SNARE assembly in stimulated platelets. Thus as a logical extension [6], we sought to investigate whether the granule fusion occurs in the absence of IKKβ or not. Thus, we employed transmission electron microscopy, to examine the structure of the granules with respect to their shape and size, and their association with the cell surface, in the PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox mice/platelets. Platelet membrane fusion was triggered using a very low dose of thrombin (0.025 U/mL), and granule-to-granule fusion was found to be absent in the PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets (as indicated by arrow), relative to controls (Figure 1A; data is quantified in Figure 1B). Nonetheless, and interestingly, granules were still able to dock to the membrane (as indicated by arrow; Figure 1A). These findings suggest that IKKβ plays a key role in membrane fusion, whereas it does not seem to play any role in granule docking.

Figure 1. PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox mice have defects in platelet in membrane fusion.

(A) IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 3 min. Platelet samples were fixed and processed for electron microscopy (EM) analysis. The samples were analyzed by transmission EM and images were obtained using Gatan software, with the scale bars indicated (n=3). (B) Individual platelet granules in the resting and stimulated (IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox) platelets were counted and presented as a bar diagram.

3.2. Phosphorylation of Bcl10 requires IKKβ, is essential for CBM complex formation and is PKCδ dependent

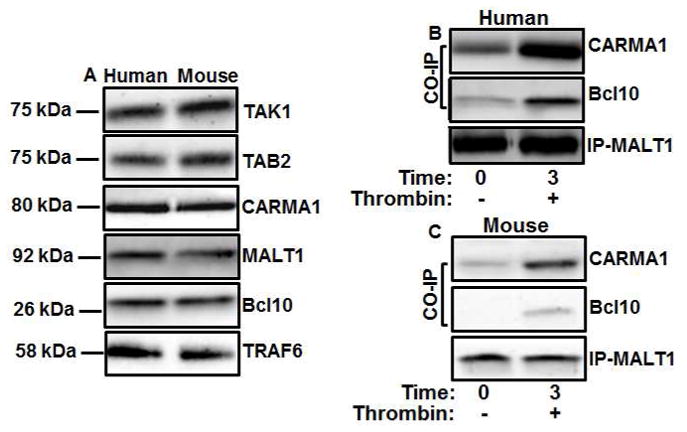

Similar to what we have shown before [6], CARMA1, Bcl10, MALT1, TAK1, and TAB2 are all present in platelets (human and mouse; Figure 2A), and CBM complex forms in these cells (Figure 2B (Human) and 2C (Mouse)). Herein, we found that TRAF6 is also present in platelets (Figure 2A). Since Bcl10 is phosphorylated in T-cell activation [26, 27], this was examined in platelets. Indeed, this was found to be the case in response to various agonists, such as thrombin, TRAP4, A23187, PMA, and collagen (Figure 3A; and densitiometric analysis is shown in Figure 3B), in a time-dependent manner. However, whether IKKβ is required for Bcl10 phosphorylation is unknown. As shown in Figure 3C, Bcl10 phosphorylation is blocked in the IKKβ deletion platelets, in response to thrombin. Furthermore, we also found that CBM complex formation is defective in the PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox/platelets, i.e., MALT1 does not associate with Bcl10 (Figure 3C). Moreover, IKKβ and phospho-IKKβ were found to be present in the CBM complex in the wild-type, but not knockout activated platelets (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained when we immunoprecipitated Bcl10 (Figure 4A and 4B). Thus, the cellular CBM complex is a dynamic structure that is rapidly formed after platelet activation. Furthermore, these findings support the notion that IKKβ-dependent phosphorylation of Bcl10 is required for CBM complex formation, and perhaps IKKβ signal transduction. Additionally, the association of IKKβ with the CBM complex may be required for Bcl10 phosphorylation. We next examined whether Bcl10 phosphorylation is required for CBM complex formation. Our results using a Bcl10 inhibitor (NBP2-29323 [28]) revealed that the phosphorylation of IKKβ and Bcl10 were inhibited (Figure 3D), which suggest that IKKβ is involved in CBM complex formation.

Figure 2. CBM complex forms in activated platelets.

(A) Extracts from resting human and mouse platelets were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-CARMA1, anti-MALT1, anti-Bcl10, anti-TAK1, anti-TAB2 and TRAF6 antibodies (n=3). Human (B) and mouse (C) platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.025 U/mL) for 3 min. Platelet lysates were precleared and then incubated with anti-MALT1. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to MALT1, Bcl10 and CARMA1 (n=3).

Figure 3. Bcl10 is phosphorylated, and IKKβ plays a critical role in CBM complex formation, in platelets.

(A) Mouse platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), collagen (2 μg), TRAP4 (1 μM), A23187 (1 μM) and PMA (100 nM) in a time-dependent manner, before being subjected to immunoblotting with anti-pBcl10 antibody (n=3). (B) Phosphorylated Bcl10 bands were denstiometrically analyzed. (C) Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and lysed. Lysates were precleared and then incubated with anti-MALT1. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to CARMA1, Bcl10, pBcl10, IKKβ, and pIKKβ as indicated (n=3). (D) Washed IKKβflox/flox platelets were preincubated with the Bcl10 inhibitor (NBP2-29323, 10 μM for 5 min), before being activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies IKKβ and pIKKβ (n=3). (E) Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were preincubated with the PKCδ inhibitor (rottlerin, 10 μM for 5 min), before being activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and lysed. Platelet lysates were precleared and then incubated with anti-Bcl10. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to Bcl10, pBcl10, CARMA1 and IKKα as indicated (n=3). (F) Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were preincubated with a general PKC inhibitor (RO-31-8220, 1 μM for 5 min), and a PKCα/β inhibitor (Gö6976, 1 μM, for 5 min), before being activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against Bcl10 and pBcl10 (n=3). (G) Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were preincubated with a PKCδ inhibitor (Rottlerin, 10 μM for 5 min) and, before being activated with 100 nM PMA, and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against Bcl10 and pBcl10 (n=3).

Figure 4. CBM complex formation, Bcl10 phosphorylation and Bcl10-induced IKKγ ubiquitination are defective in the absence of IKKβ, in stimulated platelets.

Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and lysed. Platelet lysates were precleared and then incubated with anti-MALT1 (A) or anti-Bcl10 (B). Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to MALT1, CARMA1, IKKβ, pIKKβ and pERK as indicated (A; n=3) or antibodies to MALT1, CARMA1, Bcl10 and pBcl10 as indicated (B; n=3). (C) Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and lysed. Platelet lysates were precleared and then incubated with anti-IKKγ. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to ubiquitin, IKKγ, Bcl10, and pBcl10 as indicated (n=3). (D) Washed IKKβflox/flox or PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were activated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin and lysed. Platelet lysates were precleared and then incubated with anti-Bcl10. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to ubiquitin, and Bcl10 as indicated (n=3).

Since Bcl10 contains a PKC phosphorylation consensus sequence [29], and PKC is upstream of IKKβ [6], we sought to investigate whether/which of its isoforms is involved in Bcl10 phosphorylation. It was found that the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin [5], does prevent phosphorylation of Bcl10 (Figure 3E). Furthermore, association of Bcl10 and CARMA1, and degradation of IkBα (Figure 3E) in IKKβflox/flox platelets were also impaired with rottlerin, underscoring the critical role of PKCδ (which we previously shown to be upstream of IKK/NF-κB signaling [6]). Control experiments revealed that Bcl10 is not phosphorylated in rottlerin-treated PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets (Figure 3E). As for the role of other PKC isoforms, it was observed that the general PKC inhibitor (Ro-31-8220 [5]) inhibits the phosphorylation of Bcl10 in both IKKβflox/flox and PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox, whereas the PKCα/β inhibitor (Gö6976 [5]) does not (Figure 3F). These findings suggest that PKCα/β is not involved in the phosphorylation of Bcl10. To further confirm the role of PKCδ in the phosphorylation of Bcl10, both IKKβflox/flox and PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox platelets were incubated with the PKCδ inhibitor (rottlerin) before being stimulated with PKC activator PMA. We observed that PKCδ inhibition does indeed result in the inhibition of phosphorylation of Bcl10 in both the wildtype and knockout platelets (Figure 3G).

Together, these data provide evidence that PKCδ regulates IKKβ-dependent Bcl10 phosphorylation, and the recruitment of Bcl10/MALT1 heteromers to CARMA1 (CBM complex formation).

3.3. IKKβ deletion impairs Bcl10-induced IKKγ ubiquitination in stimulated platelets

Bcl10 is known to activate IKK/NF-κB through ubiquitination of IKKγ, in a MALT1-dependent process [30]. The IKK complex contains two catalytic subunits, IKKα and IKKβ [31–35], and a regulatory subunit, IKKγ [36–38], with the former being serine/threonine protein kinases, and the latter containing several protein interaction motifs [39]. The regulatory relationship between these subunits is not well-understood in platelets. Thus, it was found that, in the absence of IKKβ (and impaired phosphorylation of Bcl10), IKKγ does not associate with Bcl10/pBcl10 and its polyubiquitination is inhibited, relative to wild-type controls, in response to thrombin (Figure 4C). Taken together, these data indicate that IKKβ is required for: 1. phosphorylation of Bcl10, 2. Bcl10/MALT1 and Bcl10/IKKγ interactions, and 3. IKKγ polyubiquitination.

Furthermore, considering the possibility that IKKγ might be a bridge between Bcl10 and IKKβ, we asked whether IKKγ has a ubiquitinated binding partner [40]. We found that Bcl10 ubiquitination was readily apparent in PMA-stimulated IKKβ+/+ platelets (Figure 4D), but interestingly not in the IKKβ−/− platelets (Figure 4D). Together, these data suggest that the assembly of the complete CBM complex is required for both Bcl10 ubiquitination and IKK/NF-κB activation [41–43].

4. Discussion

We have recently shown that IKK plays an important role in platelet membrane fusion [6], via controlling molecular complex formation (CBM complex). However, the regulatory role of IKKβ in CBM complex formation is still unknown. These issues were investigated herein, by employing a genetic/knockout mouse model system, namely the PF4-Cre/IKKβflox/flox mice. Firstly, we found that IKKβ plays a key role in membrane fusion, but not in granule docking. Secondly, we found that IKKβ is required for the phosphorylation of Bcl10, for Bcl10/MALT1 and Bcl10/IKKγ interactions, and for IKKγ polyubiquitination. Finally, the assembly of the CBM complex is required for both Bcl10 ubiquitination and IKK/NF-κB activation, in stimulated platelets.

Despite the progress that we and others have made regarding IKK/NF-κB activity in platelets [6, 23, 44, 45], a mechanistic understanding of the IKKβ upstream signaling, and its regulatory role in the context of CBM complex formation remains unknown. Our findings revealed that IKKβ deletion disrupted the formation of the CBM complex, e.g., MALT1 association with CARMA1, and that IKKβ is required for IκB phosphorylation. This indicates, for the first time, that IKKβ is essential for the formation (remodeling) of the CBM complex. To this end, Paul et al. [46] showed that TCR signals are transduced from the membrane-associated CBM complex to the cytosolic IκBα-NF-κB complex. On this basis, we believe that the assembly of distinct cytosolic signalosomes is emerging as a common, and perhaps essential, mechanism for transmitting activating signals to the IKK complex [46]. Notably at baseline, MALT1 IP brought down CARMA1 and Bcl10, whereas Bcl10 IP did not bring down CARMA1. This raises the possibility of two component complexes at baseline, namely MALT1/CARMA1 and MALT1/Bcl10. The fact that these baseline complexes do not occur in IKKβ deletion platelets indicates a role for IKKβ prior to platelet activation.

While PKC has been shown to be a key downstream regulator of CBM complex formation, the specific isoform, in platelets, remains “ill” defined. To this end, it has been shown that CARMA1 is phosphorylated by PKCθ in T-cells, which induces CBM complex formation and IKKβ activation [17, 18]. Nonetheless, phosphorylation of CARMA1 in T- and B cells was found to be mediated by PKCθ [47] and PKCβ [16], respectively, and is essential for CARMA1–MALT1 association [16]; whereas our previous platelet studies showed that PKC is upstream of IKKβ, and that PKCδ is involved in the regulation of SNAP23 phosphorylation [6]. The present studies revealed that PKCδ phosphorylates Bcl10 and regulates CBM complex formation (association of CARMA1 and Bcl10).

In T-cells, it was previously reported that IKKγ binds to ubiquitin-modified Bcl10 in the CBM complex and that disruption of Bcl10 ubiquitination markedly inhibits IKK activation [48]. This notion supports our results that IKKβ interferes with Bcl10-induced IKKγ ubiquitination in stimulated platelets.

In conclusion, we establish for the first time in platelets that IKKβ is involved in remodeling of CBM complex formation. Furthermore, this “remodeling” unveils a new platelet signaling pathway that modulates an array of responses from several receptors that engage the SNARE machinery, ultimately leading to cargo release. Collectively, our findings underscore IKKβ as dual function player, namely in the regulation of the CBM complex, as well as SNARE complex formation and membrane fusion. These data also indicate that clustering of proteins around the CBM complex promotes nonlinear and nonhierarchical signal propagation by facilitating complex interactions between protein networks. Future studies are required to better-understand how this signaling cascade regulates platelet function and contributes to thrombogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

IKKβ is involved in membrane fusion

IKKβ is required for initial formation and the regulation of the CBM complex

IKKβ regulates CBM complex via phosphorylation of Bcl10 and IKKγ polyubiquitination.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Krassimir N. Bozhilov and Mathias Rommelfanger of the University of California, Riverside Central Facility for Advanced Microscopy and Microanalysis.

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the NIH/NHLBI (RHL127592A-01; Z.A.K).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Badimon L, Suades R, Fuentes E, Palomo I, Padro T. Role of Platelet-Derived Microvesicles As Crosstalk Mediators in Atherothrombosis and Future Pharmacology Targets: A Link between Inflammation. Atherosclerosis, and Thrombosis, Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:293. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsh J. Hyperactive platelets and complications of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1543–1544. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706113162410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alshbool FZ, Karim ZA, Vemana HP, Conlon C, Lin OA, Khasawneh FT. The regulator of G-protein signaling 18 regulates platelet aggregation, hemostasis and thrombosis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2015;462:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karim ZA, Alshbool FZ, Vemana HP, Conlon C, Druey KM, Khasawneh FT. CXCL12 regulates platelet activation via the regulator of G-protein signaling 16. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1863:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karim ZA, Choi W, Whiteheart SW. Primary platelet signaling cascades and integrin-mediated signaling control ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf) 6-GTP levels during platelet activation and aggregation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:11995–12003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800146200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim ZA, Zhang J, Banerjee M, Chicka MC, Al Hawas R, Hamilton TR, Roche PA, Whiteheart SW. IkappaB kinase phosphorylation of SNAP-23 controls platelet secretion. Blood. 2013;121:4567–4574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-470468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei S, Wang H, Zhang G, Lu Y, An X, Ren S, Wang Y, Chen Y, White JG, Zhang C, Simon DI, Wu C, Li Z, Huo Y. Platelet IkappaB kinase-beta deficiency increases mouse arterial neointima formation via delayed glycoprotein Ibalpha shedding. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:241–248. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Che T, You Y, Wang D, Tanner MJ, Dixit VM, Lin X. MALT1/paracaspase is a signaling component downstream of CARMA1 and mediates T cell receptor-induced NF-kappaB activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:15870–15876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaide O, Favier B, Legler DF, Bonnet D, Brissoni B, Valitutti S, Bron C, Tschopp J, Thome M. CARMA1 is a critical lipid raft-associated regulator of TCR-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:836–843. doi: 10.1038/ni830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas PC, Yonezumi M, Inohara N, McAllister-Lucas LM, Abazeed ME, Chen FF, Yamaoka S, Seto M, Nunez G. Bcl10 and MALT1, independent targets of chromosomal translocation in malt lymphoma, cooperate in a novel NF-kappa B signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:19012–19019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D, Matsumoto R, You Y, Che T, Lin XY, Gaffen SL, Lin X. CD3/CD28 costimulation-induced NF-kappaB activation is mediated by recruitment of protein kinase C-theta, Bcl10, and IkappaB kinase beta to the immunological synapse through CARMA1. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:164–171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.164-171.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khoshnan A, Bae D, Tindell CA, Nel AE. The physical association of protein kinase C theta with a lipid raft-associated inhibitor of kappa B factor kinase (IKK) complex plays a role in the activation of the NF-kappa B cascade by TCR and CD28. J Immunol. 2000;165:6933–6940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hara H, Bakal C, Wada T, Bouchard D, Rottapel R, Saito T, Penninger JM. The molecular adapter Carma1 controls entry of IkappaB kinase into the central immune synapse. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1167–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng J, Hamilton KS, Kane LP. Phosphorylation of Carma1, but not Bcl10, by Akt regulates TCR/CD28-mediated NF-kappaB induction and cytokine production. Molecular immunology. 2014;59:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner D, Brechmann M, Rohling S, Tapernoux M, Mock T, Winter D, Lehmann WD, Kiefer F, Thome M, Krammer PH, Arnold R. Phosphorylation of CARMA1 by HPK1 is critical for NF-kappaB activation in T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14508–14513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900457106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinohara H, Maeda S, Watarai H, Kurosaki T. IkappaB kinase beta-induced phosphorylation of CARMA1 contributes to CARMA1 Bcl10 MALT1 complex formation in B cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3285–3293. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto R, Wang D, Blonska M, Li H, Kobayashi M, Pappu B, Chen Y, Wang D, Lin X. Phosphorylation of CARMA1 plays a critical role in T Cell receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Immunity. 2005;23:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sommer K, Guo B, Pomerantz JL, Bandaranayake AD, Moreno-Garcia ME, Ovechkina YL, Rawlings DJ. Phosphorylation of the CARMA1 linker controls NF-kappaB activation. Immunity. 2005;23:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cannons JL, Yu LJ, Hill B, Mijares LA, Dombroski D, Nichols KE, Antonellis A, Koretzky GA, Gardner K, Schwartzberg PL. SAP regulates T(H)2 differentiation and PKC-theta-mediated activation of NF-kappaB1. Immunity. 2004;21:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jun JE, Wilson LE, Vinuesa CG, Lesage S, Blery M, Miosge LA, Cook MC, Kucharska EM, Hara H, Penninger JM, Domashenz H, Hong NA, Glynne RJ, Nelms KA, Goodnow CC. Identifying the MAGUK protein Carma-1 as a central regulator of humoral immune responses and atopy by genome-wide mouse mutagenesis. Immunity. 2003;18:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiedt R, Schomber T, Hao-Shen H, Skoda RC. Pf4-Cre transgenic mice allow the generation of lineage-restricted gene knockouts for studying megakaryocyte and platelet function in vivo. Blood. 2007;109:1503–1506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-020362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt-Supprian M, Courtois G, Tian J, Coyle AJ, Israel A, Rajewsky K, Pasparakis M. Mature T cells depend on signaling through the IKK complex. Immunity. 2003;19:377–389. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karim ZA, Vemana HP, Khasawneh FT. MALT1-ubiquitination triggers non-genomic NF-kappaB/IKK signaling upon platelet activation. PloS one. 2015;10:e0119363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhall S, Karim ZA, Khasawneh FT, Martins-Green M. Platelet Hyperactivity in TNFSF14/LIGHT Knockout Mouse Model of Impaired Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2016;5:421–431. doi: 10.1089/wound.2016.0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren Q, Ye S, Whiteheart SW. The platelet release reaction: just when you thought platelet secretion was simple. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:537–541. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328309ec74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eitelhuber AC, Warth S, Schimmack G, Duwel M, Hadian K, Demski K, Beisker W, Shinohara H, Kurosaki T, Heissmeyer V, Krappmann D. Dephosphorylation of Carma1 by PP2A negatively regulates T-cell activation. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:594–605. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frischbutter S, Gabriel C, Bendfeldt H, Radbruch A, Baumgrass R. Dephosphorylation of Bcl-10 by calcineurin is essential for canonical NF-kappaB activation in Th cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2349–2357. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Branski RC, Zhou H, Sandulache VC, Chen J, Felsen D, Kraus DH. Cyclooxygenase-2 signaling in vocal fold fibroblasts. The Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1826–1831. doi: 10.1002/lary.21017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng H, Di L, Fu G, Chen Y, Gao X, Xu L, Lin X, Wen R. Phosphorylation of Bcl10 negatively regulates T-cell receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5235–5245. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01645-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou H, Wertz I, O’Rourke K, Ultsch M, Seshagiri S, Eby M, Xiao W, Dixit VM. Bcl10 activates the NF-kappaB pathway through ubiquitination of NEMO. Nature. 2004;427:167–171. doi: 10.1038/nature02273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiDonato JA, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IkappaB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Li J, Young DB, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regnier CH, Song HY, Gao X, Goeddel DV, Cao Z, Rothe M. Identification and characterization of an IkappaB kinase. Cell. 1997;90:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woronicz JD, Gao X, Cao Z, Rothe M, Goeddel DV. IkappaB kinase-beta: NF-kappaB activation and complex formation with IkappaB kinase-alpha and NIK. Science. 1997;278:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IkappaB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKalpha and IKKbeta, necessary for IkappaB phosphorylation and NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Kang J, Friedman J, Tarassishin L, Ye J, Kovalenko A, Wallach D, Horwitz MS. Identification of a cell protein (FIP-3) as a modulator of NF-kappaB activity and as a target of an adenovirus inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1042–1047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Natoli G, Karin M. IKK-gamma is an essential regulatory subunit of the IkappaB kinase complex. Nature. 1998;395:297–300. doi: 10.1038/26261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaoka S, Courtois G, Bessia C, Whiteside ST, Weil R, Agou F, Kirk HE, Kay RJ, Israel A. Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IkappaB kinase complex essential for NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 1998;93:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller BS, Zandi E. Complete reconstitution of human IkappaB kinase (IKK) complex in yeast. Assessment of its stoichiometry and the role of IKKgamma on the complex activity in the absence of stimulation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:36320–36326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scharschmidt E, Wegener E, Heissmeyer V, Rao A, Krappmann D. Degradation of Bcl10 induced by T-cell activation negatively regulates NF-kappa B signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3860–3873. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3860-3873.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes & development. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruland J, Duncan GS, Elia A, del Barco Barrantes I, Nguyen L, Plyte S, Millar DG, Bouchard D, Wakeham A, Ohashi PS, Mak TW. Bcl10 is a positive regulator of antigen receptor-induced activation of NF-kappaB and neural tube closure. Cell. 2001;104:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thome M, Tschopp J. TCR-induced NF-kappaB activation: a crucial role for Carma1, Bcl10 and MALT1. Trends in immunology. 2003;24:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu F, Morris S, Epps J, Carroll R. Demonstration of an activation regulated NF-kappaB/I-kappaBalpha complex in human platelets. Thrombosis research. 2002;106:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(02)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malaver E, Romaniuk MA, D’Atri LP, Pozner RG, Negrotto S, Benzadon R, Schattner M. NF-kappaB inhibitors impair platelet activation responses. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 2009;7:1333–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul S, Traver MK, Kashyap AK, Washington MA, Latoche JR, Schaefer BC. T cell receptor signals to NF-kappaB are transmitted by a cytosolic p62-Bcl10-Malt1-IKK signalosome. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sasahara Y, Rachid R, Byrne MJ, de la Fuente MA, Abraham RT, Ramesh N, Geha RS. Mechanism of recruitment of WASP to the immunological synapse and of its activation following TCR ligation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu CJ, Ashwell JD. NEMO recognition of ubiquitinated Bcl10 is required for T cell receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3023–3028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712313105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.