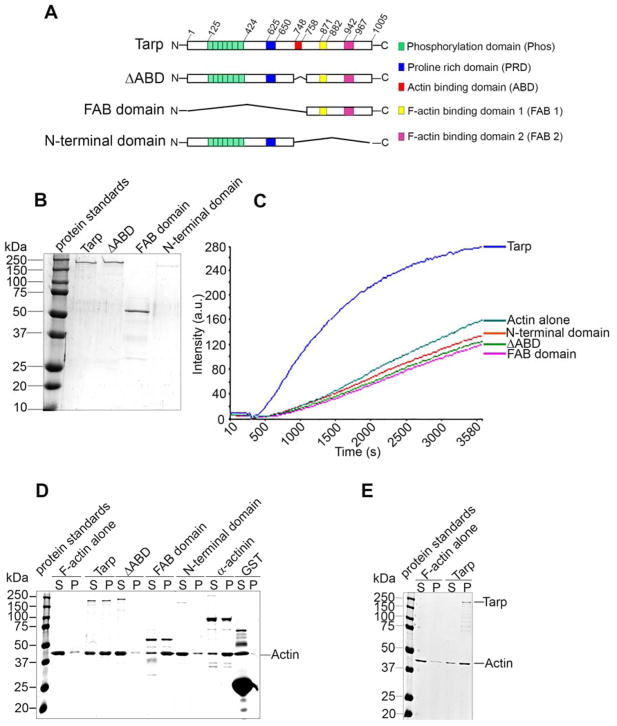

Figure 1.

The Tarp FAB domain is sufficient to bundle actin. (A) Schematics of Tarp proteins utilized in this study indicating the locations of the tyrosine rich repeat phosphorylation domain (green boxes), the proline rich domain (blue box), G-actin binding domain (red box), and F-actin binding domains 1 (yellow box) and 2 (pink box). The numbers indicate amino acid positions encoded within the C. trachomatis tarP gene. The “∧” indicates amino acids deleted from the wild type sequence. Mutant Tarp clones included Tarp lacking the G-actin binding domain (ΔABD) as well as Tarp fragments representing only the F-actin binding domains (FAB domains) or a Tarp truncation excluding all known actin (both G- and F-) binding domains (N-terminal domain). (B) Purified Tarp and Tarp mutants depicted in (A). (C) Tarp proteins described in panels A and B were assessed in pyrene actin polymerization assays. Tarp proteins were incubated with monomeric pyrene-labeled actin. An increase in actin polymerization after the addition of polymerization buffer at 300 s was measured as arbitrary fluorescence intensity [Intensity (a.u.)] over time [Time (s)]. The data are representative of three repeated experiments. (D) Purified recombinant Tarp proteins were incubated with preformed filamentous actin (F-actin) and isolated by low-speed centrifugation. Protein supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. α-actinin and GST served as positive and negative controls, respectively. (E) Globular actin (G-actin) along with polymerization buffer was incubated with (Tarp) or without (F-actin alone) purified recombinant Tarp and isolated by low-speed centrifugation. Protein supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining.