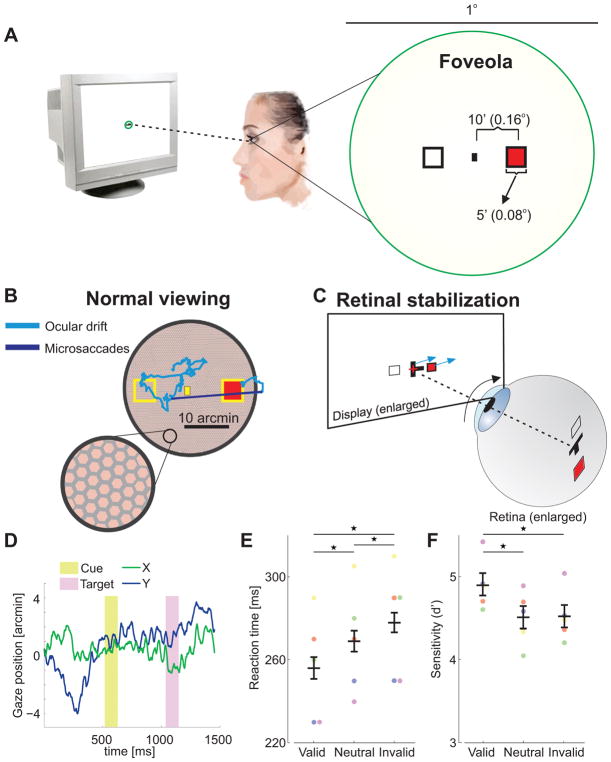

Figure 2. Attention control within the foveola (Exp. 2).

(A) A spatial cueing task in the foveola requires precise presentation of stimuli at nearby locations. (B) This requirement is challenged by incessant small eye movements, which normally displace the retinal image over the photoreceptors mosaic by an area as large as the foveola itself. (C) Stimuli were maintained at the desired eccentricities by moving them in real time, under computer control (cyan arrows), to compensate for the observer’s eye movements (black arrow). (D) An example of eye movements during the course of a trial. (E) Average reaction times and (F) accuracy for different trial types across observers (n=5). Differences in reaction times between valid and invalid trials were statistically significant for all individual observers (two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum tests. S1: p=0.004; S2: p=0.022; S3: p=0.039; S4: p=0.0009; S5: p=0.0009). Error bars are 95% CI. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (Tukey HSD post-hoc tests. Reaction times: valid trials vs. neutral trials, p=0.0074; valid vs. invalid, p=0.0003; neutral vs. invalid, p=0.0472. Sensitivity: valid vs. neutral, p=0.0135; valid vs. invalid, p=0.0128; neutral vs. invalid p=0.9992). Conventions are as in Fig. 1.