Progress in the physical and social sciences requires new tools for measuring phenomenon that were previously believed un-measurable and a conceptual framework for interpreting such measurements. There has been much progress on both fronts in the measurement of subjective wellbeing (SWB) in recent years. Subjective wellbeing “refers to how people experience and evaluate their lives and specific domains and activities in their lives” (NAS 2014). We summarize several important advances in the measurement of SWB and highlight key remaining methodological challenges that must be addressed to develop a credible national indicator of SWB, but space does not permit a comprehensive literature review. We also discuss recent attempts to incorporate data on SWB in official statistics and policy decisions by national governments and international organizations.

Validity and Comparability of Reports of Subjective Well-Being

Subjective wellbeing is necessarily measured by respondents’ self-reports evaluating their life and feelings. In some fields subjective reports are the standard; for instance, in the assessment of pain and fatigue, and are indispensable tools for research and for providing healthcare. Although there have been longstanding concerns about the meaning of subjective reports, an emerging body of evidence finds that self-reports are related to biological processes and health outcomes, increasing confidence in the validity of such measures. For example, experimental studies find that self-reports of the extent of pain experienced in response to thermal stimuli are associated with changes in blood flow to brain regions known to process pain (Coghill, et al., 2003). Several studies have shown a correspondence between subjective reports of affect and experience, on the one hand, and immunological and hormonal measures on the other (Cohen, 2003 and Smyth, 1998). Mortality has also been associated with low levels of SWB (Steptoe, et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, additional evidence is needed to support the validity of between-group comparisons; for example, when comparing SWB of people in different countries or different demographic groups (men v. women; young v. old). Differential reporting styles, including interpretation of question content and response scales, by groups, has the potential to yield misleading conclusions, and some rankings of countries have been questioned on these grounds.

A recent technique for evaluating and adjusting interpersonal and intergroup differences in self-reports is the “vignette approach.” In this approach, questions about the constructs under investigation (e.g., health, wellbeing, pain) are preceded by vignettes that describe an individual at some intensity of the concept, providing an explicit comparison standard for the subsequent rating, although there are potential environmental factors that may interact with the standard and confound the comparison, such as differences in the quality of health care across communities. Responses to the vignettes by different groups (e.g., countries) can be compared, and scales adjusted if systematic intergroup differences emerge from identical scenarios presented in the vignettes (see Kapteyn, et al., 2004). This has proved a promising approach for assessing subjective health appraisals, and is currently being applied to wellbeing reports as well.

Interpretation and use of response scales (i.e., the options for answering questions) is likely to vary according to past experiences, cultural background, genetic factors, and immediate context. Well-known response options are verbal scales (e.g., “Extremely satisfied” through “not at all satisfied”) and numeric rating scales (e.g., 0 through 10 anchored scales, with 0 indicating the absence of some feeling). Advances have been made in understanding how people use response scales to answer questions. For example, based on studies of individual difference in densities of taste receptors on their tongues, Bartoshuk (2014) has described a phenomenon of scale elasticity, wherein self-reports with standard response scales of taste sensation were invalid, because response options had different meanings for two groups of tasters. Supertasters had a “stretched-out” scale, but this feature is lost in current response scales. The same logic may prove useful in rating scales for SWB.

Yet another validity issue concerns the extent to which people adapt to their circumstances, and the implications of adaptation for interpreting subjective wellbeing measures. A critical distinction in this literature is a shift in how scales are used, where extreme events can result in “recalibration” of scale (Ubel, et al., 2010), as opposed to true adaptation. In the first case, changes in wellbeing are not due to actual differences in experience or evaluation, but simply to how the scale was used, whereas true adaptation is defined by changes in emotional experience. There is evidence that people shift their use of scales and that they can adapt to difficult circumstances; for example, adaption has been found in response to physical disabilities or winning a lottery; (see Luhmann, 2012, for a recent meta-analysis of adaptation to major life events). But adaptation is not a uniform process, and some circumstances and aspects of SWB appear relatively more or less resistant to adaptation.

Conceptual Framework

Progress has also recently been made on a conceptual framework for SWB, a topic that remains, in our view, the most important obstacle to efforts to develop a comprehensive national indicator of SWB. In innovative new work Benjamin, et al. (2014) provide a framework in which individuals’ utility depends on several “fundamental aspects,” such as material well-being, life satisfaction, emotional experience, health, etc., and the fundamental aspects are non-overlapping. Following standard economic logic, components of utility can be aggregated based on the extent to which individuals would be willing to trade an improvement in one aspect against an improvement in another, on the margin. This method implemented by posing a series of hypothetical choices between situations that involve different dimensions of SWB, which are similar to vignettes. By observing individuals’ preferences for the various choices, one can infer the tradeoffs involved in different dimensions of SWB, and measure the marginal valuations that individuals implicitly assign to different aspect of SWB. These marginal valuations provide weights for aggregating different aspects of SWB, just as prices (marginal utilities) provide appropriate weights for aggregating components of the Gross Domestic Product under certain assumptions.

Although this research is in its infancy and objections can be raised about its reliance on revealed preference, it provides a coherent framework for aggregating dimensions of SWB based on individuals’ choices. Further refinements of this approach, perhaps including actual choices as opposed to hypothetical ones, may advance the measurement of SWB.

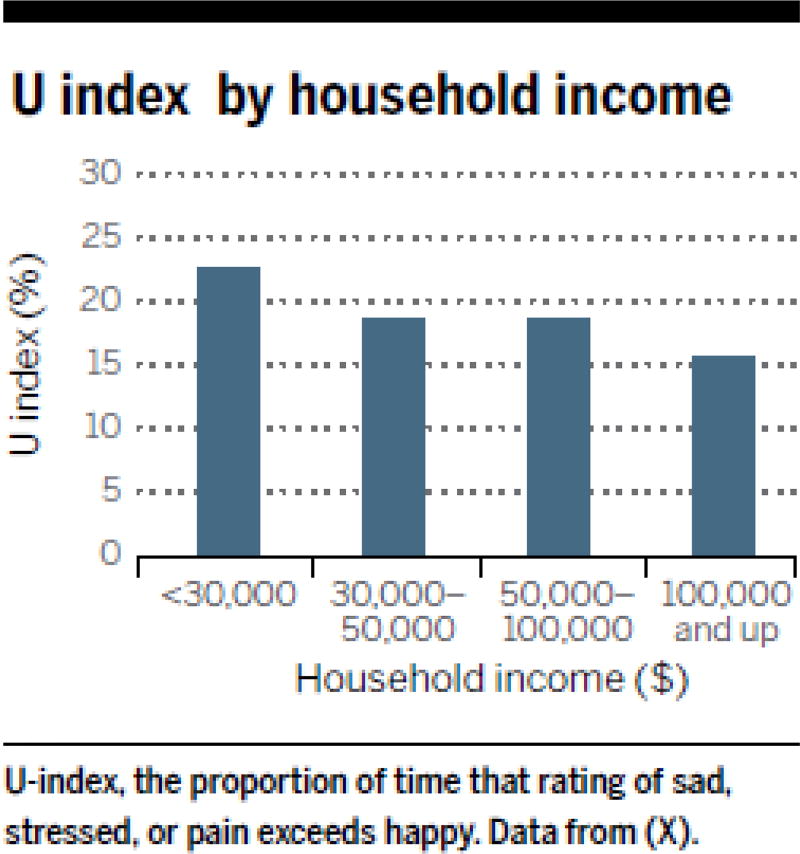

Kahneman and Krueger (2006) seek to side step many of the requirements for a comprehensive index of SWB (such as interpersonal comparability) by focusing only on experiential SWB and measuring the percentage of time that people spend in an unpleasant state, which they call the U-index. An unpleasant state is defined as an episode in which the intensity of a negative emotion is greater than the intensity of positive emotions (e.g., rating pain or anger as a more intense feeling than happiness or joy during that episode). They justify the U-index in part by arguing that policymakers often care more about minimizing misery than maximizing happiness, a theme echoed in the recent report on SWB from the National Academies (NAS 2014). The U-index can be constructed with the Day Reconstruction Measure (DRM), which collects time use data together with emotional experience. The U-index is robust in the sense that different individuals and groups can interpret the scales differently, as long as they consistently apply their interpretation to positive and negative emotions. The U-index is related to but conceptually distinct from more traditional measures of positive and negative affect (measured with momentary and diary approaches), in that the U-index emphasizes that one dominant negative emotion can color an entire episode.

Until more progress is made toward developing a credible, comprehensive index of SWB, we would emphasize the importance of separately measuring the key components of SWB (e.g., satisfaction with life, positive emotional experience, negative emotional experience, meaning in life) and keeping them distinctive.

Official Measures and Guidelines

Since the watershed report of the Sarkozy Commission in 2009, which recommended adding wellbeing measures as supplements to existing indicators of societal progress, there has been much follow-up activity by governmental bodies and international organizations. First, in a pioneering effort the U.K. Office of National Statistics (ONS) initiated a program to measure SWB in its Annual Population Survey. Notably, evaluative (“satisfaction” with life), eudaimonic (meaning), and hedonic SWB (affect in everyday life) were surveyed. However, the assessment was minimal (only four questions), and lacks information on actual time use or events in people’s lives. To partly address these concerns, ONS plans to conduct more detailed surveys of SWB. More fundamentally, however, the proper way to combine ONS’s measures of SWB into a comprehensive measure remains unresolved.

Next, OECD (2013) published an extensive report on measuring SWB to guide national statistical offices and presented a detailed methodological critique of ongoing efforts. This report is essential reading for any organization considering implementing a systematic program to measure and monitor SWB. The OECD’s Better Life Index (oecdbetterlifeindex.org) also cleverly finesses the problem of how to aggregate different components of wellbeing by allowing users to set their own weights.

Then in 2014 the National Research Council of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences issued a report focused on hedonic wellbeing and policy (NAS, 2014). This report stressed the importance of considering both happiness and misery in the conceptualization of SWB. It also supported a broader definition of hedonic wellbeing (called Experiential WB), one that includes pain and other forms of suffering, which the panel considered important for policy purposes. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has incorporated an affective module in the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) in 2010 and 2012 to combine SWB data (happy, pain, sad, stress, tired, meaningful) with time use information during representative periods of the day. The NAS report highlighted that, “The ATUS SWB module is practical, stable, inexpensive, and worth continuing as a component of ATUS. Not only does the ATUS SWB module support research; it also generates information to help refine SWB measures that may be considered for future additions to official statistics” (NAS Report, p. 117).

A striking feature of the OECD and NAS reports is their optimism about the future prospects of SWB measures. And this year a commission sponsored by the Legatum Institute in the U.K. issued a report on wellbeing and policy that stated “…we should measure wellbeing more often and do so comprehensively…. This would help governments improve policies, companies raise productivity, and people live more satisfying lives.” The United Nations also launched initiatives on wellbeing and sustainability (e.g., the International Day of Happiness). Finally, the OECD has assembled yet another “high level” commission to provide in-depth analyses of topics that could be informed by wellbeing research, such as income inequality.

Conclusion

Advances in the measurement of SWB are profoundly influencing social science research and policy analysis. SWB measures have become key outcome measures in program evaluation research, often yielding deeper insights than traditional measures. For example, 10 to 15 years after the launch of the Moving to Opportunities experiment, which randomly offered some public housing families the opportunity to move to less-disadvantaged neighborhoods, significant improvements were found for components of SWB (distress, depression, anxiety, calmness) but not for economic (employment, earnings) and educational outcomes (Ludwig, et al. 2013). Likewise, evaluations of the Oregon Medicaid expansion have found significant improvements in subjective outcomes, including depression and self-reported health, but more mixed results concerning physical health (Finkelstein, et al., 2012). Because individuals and policymakers value subjective outcomes, and because such outcomes appear to be affected by major policy interventions, measures of SWB are likely to play an increasingly important role in policy evaluation (Diener, 2013) and decisions in areas ranging from housing and health care to the environment and transportation.

Further advances in the measurement of SWB and the conceptual framework for combining various measures of SWB are needed before sufficient consensus can be reached to support a comprehensive, official measure of SWB that can be compared at the national level. In the meantime, comparisons of the various components of SWB, with a particular focus on negative emotional experiences, strikes us a reasonable agenda for national statistical agencies and researchers.

Figure 1.

U-index, the proportion of time that rating of sad, stressed, or pain exceeds happy. Data from (X).

Acknowledgments

The authors have participated in several of commissions and panels discussed here. ABK was a member of the 2009 Sarkozy Commission. AAS chaired the National Academy of Science’s “Panel on measuring subjective well-being in a policy-relevant framework.” ABK and AAS are current members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s “High Level Expert Group on Wellbeing.” Financial support from the National Institute on Aging Roybal Grant P30AG024928 is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Bartoshuk L. The Measurement of Pleasure and Pain. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2014;9(1):91–93. doi: 10.1177/1745691613512660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin D, Heffetz O, Kimball M, Szembrot M. Beyond happiness and satisfaction: Towards national well-being indices based on stated preference. 2013 doi: 10.1257/aer.104.9.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Hamrick N. Stable individual differences in physiological response to stressors: implications for stress-elicited changes in immune related health. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(6):407–414. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghill RC, McHaffie JG, Yen Y. Neural correlates of interindividual difference in the subjective experience of pain. PNAS. 2003;100:8538–8542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430684100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. The Remarkable Changes in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):663–666. doi: 10.1177/1745691613507583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger A. Developments in the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006 Winter;20(1):3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn A, Smith JP, vanSoest A. Vignettes and self-reports of work disability in the United States and the Netherlands. American Economic Review. 2007;97:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M, Hofmann W, Eid M, Lucas RE. Subjective Well-Being and Adaptation to Life Events: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(3):592–615. doi: 10.1037/a0025948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Subjective well-being: Measuring happiness, suffering, and other dimensions of experience. National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2013. Mar 20, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, Ockenfels MC, Porter L, Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH, Stone AA. Stressors and mood measured on a momentary basis are associated with salivary cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(4):353–370. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubel PA, Peeters Y, Smith D. Abandoning the language of "response shift": a plea for conceptual clarity in distinguishing scale recalibration from true changes in quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):465–471. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]