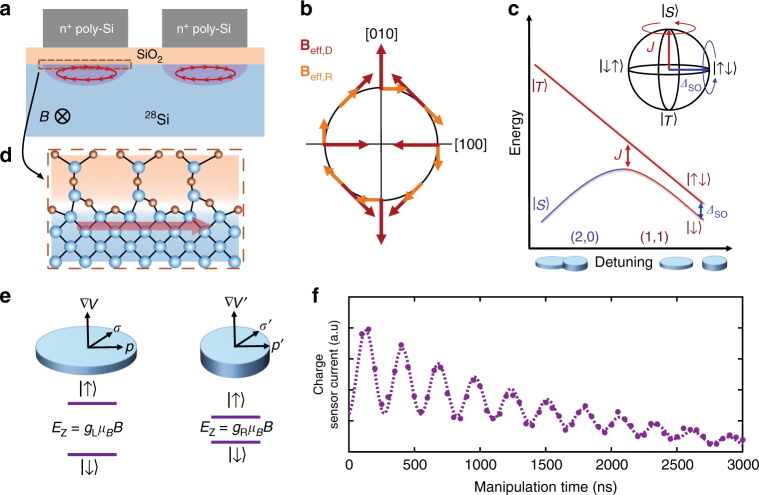

Fig. 1.

MOS spin–orbit-driven singlet–triplet qubit. a Cartoon representation of the interface spin–orbit interaction. For an electron confined to a QD, an in-plane magnetic field will cause a finite momentum at the interface which, in the presence of broken inversion symmetry, leads to a spin–orbit interaction. The position of the QDs presented in this work, relative to the gates, differs from what is portrayed here (see Supplementary Fig. 2). b Schematic example of the effective spin–orbit field due to the Dresselhaus (red) and Rashba (orange) interactions for in-plane electron momentum. c Schematic energy diagram of the DQD near the (2, 0) → (1, 1) charge transition, showing the energy of the singlet and triplet states as a function of QD–QD detuning, . Near the interdot transition ( = 0), the exchange energy, J, dominates the electronic interaction and drives rotations about the Z-axis (red arrow in inset). Deep into the (1, 1) charge sector ( > 0), J is small and the electronic states rotate about the X-axis due to a difference in Zeeman energy between each QD (blue arrow in inset). d Details of the interface at the inter-atomic bond level govern the spin–orbit interaction. e The local electrostatic environment of each QD leads to different momenta and electric fields at the interface and, thus, distinct spin–orbit interactions and Zeeman energy splitting. f Charge sensor current as a function of time spent deep in the (1, 1) charge sector, where higher current indicates a higher probability of measuring a singlet state. The oscillations indicate clear X-rotations due to a difference in spin–orbit interaction in each QD