Abstract

Background:

Adolescence, a psychologically vulnerable stage of life, when coupled with stressful environment such as institutional homes, may result in high psychiatric morbidity. These psychiatric disorders including depression are detrimental to the psychological development in adolescents.

Aims and Objectives:

The objectives of the study were to describe and study the extent of depression in adolescent boys and girls living in institutional homes and to study the association between depression and externalizing and Internalizing behaviors among adolescents in institutional homes.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional descriptive study was done on 150 adolescents staying in institutional homes in Visakhapatnam city. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data. Patient Health Questionnaire was used to screen for Depression. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was used to score for externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Statistical analysis was done using descriptive statistics and tests of association. P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results:

Clinical Depression was found in 19 (12.7%) out of 150 adolescents. Subclinical mild depression was found in 19.3% of the sample. Depression was found to be significantly associated with gender and academic performance. Externalizing and internalizing behaviors were positively correlated with depression while prosocial behavior was negatively correlated with depression.

Conclusion:

Depression has high prevalence in institutionalized adolescents. Those adolescents who show signs of externalizing or internalizing behaviors should be especially screened for depression. Further research should be done to collect more data in this regard and to focus on designing interventions for its prevention, screening, and treatment.

Keywords: Adolescents, depression, externalizing, institutional homes, internalizing

Introduction

Adolescence is associated with many physical, emotional, psychological, and social changes in children. They experience intense emotions and may go through many stressful events in this period.[1] These rapid changes in all aspects of their life affect their mental health and increase the risk of depression.[2] The concern regarding adolescent depression has recently increased as it is linked to the rise in the rate of suicides in this age group.[3] The National Mental Health Survey (2015–2016) has reported a prevalence rate of 0.8% of depression among 13–17-year-old children in India.[4]

Depression is linked to both genetic as well as environmental factors.[5] The major risk factors for adolescent depression are family history of depression, childhood traumatic experience of parental loss, stressful life events, educational, and career aspirations and substance abuse.[6,7] Other factors such as female gender, socioeconomic status, race, religion, geography, and concomitant medical illness are also associated with depression.[7]

Research has shown that prevalence of depression among institutionalized children was significantly higher compared to children living with their families.[8] The major causes for the children to be institutionalized are loss of parents, poverty, disability, abuse, neglect, and abandonment.[9] In India, the traditional joint/extended family system played a role in taking care of the needs of the child who lost his/her parents but currently nuclear family system is predominant. This leads to the increase in child destitution and the institutional care is becoming the alternative supporting care system for these children. Even the best institutions cannot substitute for the family care completely.[10] Research studies have shown that traumatic life experiences and institutional care could result in serious psychological problems.[11]

Depression is one of the common psychological issues faced by institutionalized children. Ramagopal et al. found 35% prevalence of depression among institutionalized children in Tamil Nadu in the age group of 12–18 years.[12]

Dar et al. study showed the prevalence of depression among children living in institutional home in Kashmir to be 7.76%.[11] In a study done by Fawzy and Fouad, children were recruited from four orphanages in Egypt and found the prevalence rate of depression 21% and low self-esteem of 23% among them.[13] Depression among adolescents is associated with dangerous psychosocial consequences such as suicide, substance abuse, and academic failure.[8,14]

Studies have also shown that institutionalized children had consistently higher rates of externalizing behaviors such as hyperactivity and conduct problems and Internalizing behaviors such as emotional and peer problems compared to children from the community sample.[15] These behavioral and emotional problems also increase the child's vulnerability to other psychiatric problems including depression.[16]

There is a limited pool of data focusing on mental health of institutionalized adolescents in India. To further understand and fill in the lacunae of information on psychological well-being of this group, we have done as a cross-sectional, descriptive study with objectives of studying the extent of depression, and its association with externalizing and internalizing behaviors in institutionalized adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Study type and setting

This study is a cross-sectional, descriptive study. It was set in the institutional homes for children in Visakhapatnam City in Andhra Pradesh, India.

Study sample

A pilot study was done on 15 adolescents staying in Institutional homes and 10% of these children were found to be having clinical depression. Using the formula for sample size calculation [17] with 95% confidence interval and 0.05 expected margin of error the required study sample came to be 138. Our final study sample was 150 adolescents drawn from six institutional homes in Visakhapatnam city.

Inclusion criteria

Boys and girls between ages of 12 and 17 years and staying in institutional homes in Visakhapatnam were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Children who were having regular contacts with parental family through vacation or regular weekend visits or those whose duration of stay in the home was <1 month were excluded from the study. Children who were suffering from intellectual disability and severe chronic medical illness were also excluded from the study. We have also excluded Juvenile delinquents from the current study.

Ethics

For the current study, ethics committee approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of a tertiary care hospital. The permission for access to institutional homes for the children was obtained from the Chairman of Child Welfare Committee, Visakhapatnam. Since the study sample consisted of minors, informed consent was taken from the Directors/Superintendents of the institutional homes. The data were collected from 6 Institutional Homes which included both the Government and Nongovernment Organizations. The names of the children and the institutional homes were kept confidential.

Tools of the study

Semi-structured sociodemographic questionnaire was used for collection of data regarding gender, reason for being in the institute, age of admission, years of stay in the Institutional homes, and academic performance.

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ 9) was used to assess for depression and its severity.[18] It has been statistically validated for assessing depression in adolescents.[19,20] We have used the validated Telugu translation of PHQ-9 in our study.[21]

The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) was used for behavioral screening of adolescents in the current study. The SDQ has a specificity of 80% and sensitivity of 85% in identifying psychiatric diagnosis in 4–17-year-old children and adolescents.[22] It has five sub scales: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior. Among these, emotional and peer problems subscales denote internalizing behaviors while hyperactivity and conduct problem subscales denote externalizing behaviors.[23,24,25]

Procedure

The investigating team visited the Institutional homes and collected the data from the primary caretaker and the child separately. The sociodemographic questionnaire was filled in by interviewing the child, primary caretakers, and from their individual files. The PHQ-9 was self-administered to the children. The SDQ was filled in by the primary caretaker of each child. The duration of participation of each interviewee was around 15–20 min.

Statistical analysis

The data were coded in SPSS 16.0 (Statistical Package for social sciences, IBM Corporation) to analyze the qualitative and quantitative data. Descriptive statistics for sociodemographics and depression severity were expressed in frequency and percentages and presented in the tables. To find the strength of association between depression and the demographic variables Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test was conducted wherever applicable. The correlation of externalizing, internalizing, and prosocial behavior scores to depression (PHQ-9) scores was done using Spearman's Rho Correlation test. The results are presented in tables, and the multistage scatter plots. All the figures have been rounded off to two decimal places, and P < 0.05 is taken as significant.

Results

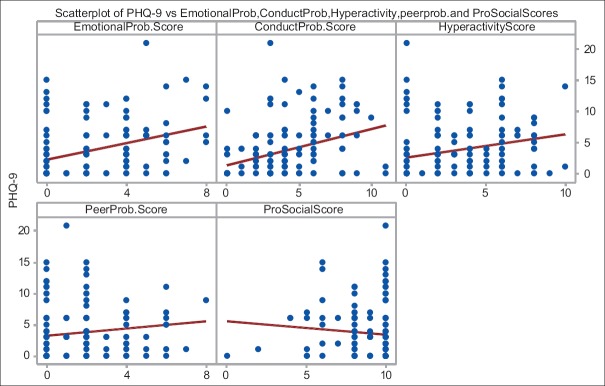

In the present study, the sample population was 150 adolescents from the Institutional homes in Visakhapatnam City. Among the total sample, 103 (68.7%) were boys, and 47 (31.3%) were girls. These adolescents were staying in these homes due to abandonment by family (47.3%) death of parents (30.7%) or having run away from their families (22%). Most of them had been staying in the institutional homes for a period of 1–5 years (43.3%) with some staying more than 5 years (33.3%) and others less than a year (23.3%). Out of 150, a total of 76 (50.7%) had been admitted into the home at above 10 years of age, while 55 (36.7%) were admitted between 5 and 10 years of age and only 19 (12.7%) admitted below 5 years of age. In terms of academic performance, 75 (50%) adolescents were reported to be average by their teachers (50%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographics of the study sample

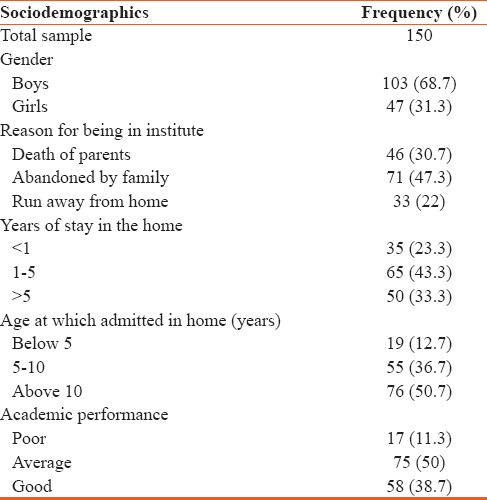

In our study, using PHQ-9 scale and taking 10 as the cutoff score, 19 out of 150 adolescents were diagnosed with clinical depression (12.7%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of depression among adolescents in institutional homes

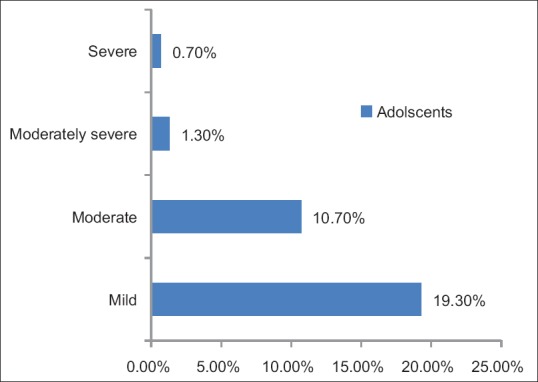

The severity of depression was assessed using PHQ-9 scale, and results showed that 19.3% of adolescents were having mild depression followed by adolescents with moderate depression (10.70%), moderately severe depression (1.30%), and severe depression (0.7%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Severity of depression

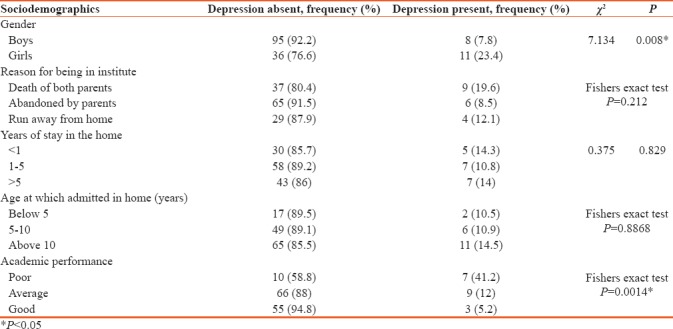

In the current study, those adolescents who were admitted because of death of parents or had been in the institutional home for less than a year or were admitted at age more than10 years were more likely to have depression, but the differences were not statistically significant. Depression in adolescents was seen to be significantly associated with gender and academic performance. More number of girls (23.4%) than boys (7.8%) was having depression. Adolescents having poor academic performance (41.2%) were found to be more diagnosed with depression than those with good academic record [Table 3].

Table 3.

The association between depression and sociodemographics

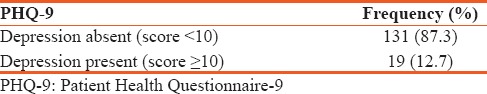

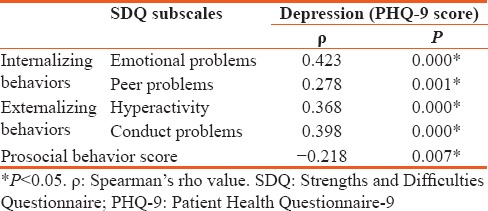

In the present study, scatter plots were constructed, and the Spearman's rho Correlation test was done to see the correlation between SDQ subscales and PHQ-9 scale scores. The tests showed a statistically significant positive correlation of internalizing behaviors (emotional and peer problems) and externalizing behaviors (hyperactivity and conduct problems) with depression. It also showed that prosocial behavior was negatively correlated with depression [Figure 2 and Table 4].

Figure 2.

Scatter plot showing correlation between Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire subscales and Patient health questionnaire-9

Table 4.

Spearman’s rho correlation between Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire subscales and depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scale)

Discussion

Institutionalized adolescents are vulnerable for depression due to social deprivation and other environmental risk factors.[26] Depression in young people puts them at an increased risk of later adverse psychosocial outcomes such as nicotine and alcohol dependence, suicide attempt, educational underachievement, and unemployment.[27] Studies have shown that children under institutional care had higher level of depression than children from the community sample.[8,28] Keeping in consideration that these young adults are the future of our society, their psychological health and wellness need to be well looked after.

We conducted our study on 150 adolescents from the institutional homes in Visakhapatnam city. Among these adolescents, the prevalence of depression was found to be 12.7% with 19.3% having mild depression, 10.70% having moderate depression, 1.30% having moderately severe depression, and just 0.7% having severe depression. Mild depression in adolescents is more likely to go undiagnosed unless screened for.

Other studies in India on depression among institutionalized children have thrown up a wide range of results. A study done in Kashmir by Dar et al. showed 7.76% prevalence of depression among children living in the orphanages.[11] Another study done in Tamil Nadu by Ramagopal et al. showed the prevalence of 35% among institutionalized children. In this study 52% had mild depression, 23% had moderate depression, 14% had severe depression, and 9% had very severe depression.[12] Bhat et al. study showed the prevalence of major depressive disorder to be 13.75% among institutionalized adolescents of district Kupwara in Kashmir.[29] Studies done elsewhere in the world showed prevalence rate ranging between 14.61% and 25% among institutionalized adolescents.[8,28,30] A study done by Ibrahim et al. found the prevalence of depression to be 20% among 200 children in orphanages of Dakahlia governorate, Egypt.[30] These differences in the rates of prevalence might be due to difference in the sample size, assessment tools, sociocultural, and demographic factors.

In the present study, significant association was found between gender and depression among institutionalized adolescents. In our study, 11 out of 47 girls and 8 out of 103 boys were having depression. More adolescents among girls (23.4%) than boys (7.8%) were having depression. Gender differences in the prevalence of depression are found among community samples of adolescent and adults also with male-to-female ratio of 1:2.[31] In a study done Ibrahim et al., among institutionalized children, girls were about 46 times more likely to have depression than boys.[30]

In the present study, poor academic performance was also significantly associated with depression in institutionalized adolescents. Academic underachievement has been associated with presence of depression by other studies also.[8,28] A study done by Hysenbegasi et al. showed that depressed students reported a pattern of increasing interference of depression symptoms with academic performance and results also showed the protective effect and academic improvement with the diagnosis and treatment of the depressive symptoms.[32]

In the present study, those who were orphans, those who had been recently admitted, and those who were put in institutionalized homes at above 10 years of age also had higher frequency of depression than others but the differences were not statistically significant. A study done by Ong et al. showed that institutionalized children whose parents were dead, divorced, or separated had higher levels of depression than others.[33] More research on a wider scale can be undertaken to explore these factors further.

In the present study, positive correlation was found between both internalizing behaviors (emotional and peer problems) and externalizing behaviors (conduct problems and hyperactivity) with clinical depression. This is in consistence with other studies which have shown that behavioral and emotional problems increase the child's vulnerability to other psychiatric problems including depression. A longitudinal study by Toumbourou et al. from early childhood through mid-adolescence using a community-based Australian birth cohort found that internalizing behaviors contributed to the prediction of subsequent depressive symptoms.[16] Another study showed that externalizing problems were associated with negative emotionality, especially anger and while internalizing problems were associated with low impulsivity and sadness and somewhat with high anger.[34] This makes a point that if adolescents show signs of externalizing or internalizing behaviors, they should be screened for depression. While hyperactivity, conduct, emotional, and peer problems by themselves have an adverse effect on the psychological functioning of an adolescent, but when further complicated by association to depression, they become very debilitating indeed. Studies have shown that periodic somatic and psychological health assessments, well-timed interventions and treatment on the psychosocial well-being of institutionalized children showed significant improvement in depression and other problem behaviors.[35,36]

In the present study, the prosocial behavior is negatively correlated with depression. It means that children who had difficulty making friends or becoming a part of close social network were more likely to have depression. Studies have shown that prosocial behavior moderated the effects of stress on positive affect, negative affect, and overall mental health and wellbeing.[37,38] Thus, enhancing the prosocial behaviors among adolescents is helpful in reducing the occurrence of depression.

Limitations

The drawback of our study is the limited sample size and being confined to one city.

Future directions

Multicentric studies with larger sample sizes using general population as controls should be done get a clearer picture of depression in institutionalized adolescents. Furthermore, proper and timely interventions may be designed to reduce psychological morbidity in institutionalized children.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the vulnerability of adolescents staying in institutional homes to depression. Study also highlighted the association of depression with gender and academic Performance. In this study, while externalizing and internalizing behaviors were positively correlated with depression, prosocial behavior was negatively correlated to it. Therefore, institutionalized adolescents showing signs of hyperactivity, conduct problems, emotional or peer problems should be screened for depression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Institute of Mental Health. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Bethesda MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; [Last updated on 2017 Apr; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 03]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/chil-and-adolescent-mental-health/index.shtml. [about 2 screens] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental Health America. Depression in Teens. U.S.A: Mental Health America; [Last updated on 2017; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 03]. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/conditions/depression-teens. [about 2 screens] [about 2 screens] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161878. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. National Mental Health Survey of India 2015-16. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; [Last updated on 2016 Oct 7; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 05]. Available from: http://www.indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/Docs/Summary.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells VE, Deykin EY, Klerman GL. Risk factors for depression in adolescence. Psychiatr Dev. 1985;3:83–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnakumar P, Geeta MG. Clinical profile of depressive disorder in children. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:521–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dell'Aglio DD, Hutz CS. Depression and school achievement of institutionalized children and adolescents. Psicol Reflex Crít. 2004;17:351–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wearelumos.org. Drivers of Institutionalisation. USA: Lumos Foundation USA Inc; [Last updated on 2015 Jun 12; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 05]. Available from: https://www.wearelumos.org/stories/drivers.institutionalisation-0. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta N. Child Protection and Juvenile Justice System. Mumbai: Child Line India Foundation; [Last updated on 2008; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.childlineindia.org.in/pdf/CP-JJ-CNCP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dar MM, Hussain SK, Qadri S, Hussain SS, Fatima SS. Prevalence and pattern of psychiatric morbidity among children living in orphanages of Kashmir. Int J Health Sci Res. 2015;5:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramagopal G, Narasimhan S, Devi LU. Prevalence of depression among children living in orphanage. Int J Contemp Pediatri. 2016;3:1326–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fawzy N, Fouad A. Psychosocial and developmental status of orphanage children: Epidemiological study. Curr Psychiatry. 2010;17:41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emery PE. Adolescent depression and suicide. Adolescence. 1983;18:245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erol N, Simsek Z, Münir K. Mental health of adolescents reared in institutional care in turkey: Challenges and hope in the twenty-first century. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:113–24. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toumbourou JW, Williams I, Letcher P, Sanson A, Smart D. Developmental trajectories of internalising behaviour in the prediction of adolescent depressive symptoms. Aust J Psychol. 2011;63:214–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel WW. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allgaier AK, Pietsch K, Frühe B, Sigl-Glöckner J, Schulte-Körne G. Screening for depression in adolescents: Validity of the patient health questionnaire in pediatric care. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:906–13. doi: 10.1002/da.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phqscreeners. Instruction Manual. USA: Pfizer; [Last updated on 2010 Apr; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.phqscreeners.pfizer.edrupalgardens.com/sites/g/files/g10016261/f/201412/instructions.pdf. [about 2 screens] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman R, Ford T, Corbin T, Meltzer H. Using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) multi-informant algorithm to screen looked-after children for psychiatric disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13(Suppl 2):II25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-2005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB. When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:1179–91. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flouri E, Midouhas E. School composition, family poverty and child behaviour. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:817–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SDQ: Information for Researchers and Professionals about the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaires. [Last updated on 2012 Jan 1; Last accessed on 2017 Aug 15]. Available from: http://www.sdqinfo.com/a0.html.

- 26.MacLean K. The impact of institutionalization on child development. Dev Psychopathol. 2003;15:853–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:225–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wathier JL, Dell'Aglio DD. Depressive symptoms and stressful events in children and adolescents in the institutionalized context. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Grande Do Sul. 2007;29:305–14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatt AA, Rahman S, Bhatt NM. Mental health issues in institutionalized adolescent orphans. Int J Indian Psychol. 2015;3:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim A, El-Bilsha MA, El-Gilany AH, Khater M. Prevalence and predictors of depression among orphans in Dakahliaâ s orphanages, Egypt. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health. 2012;4:2036–43. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wade TJ, Cairney J, Pevalin DJ. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:190–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2005;8:145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ong KI, Yi S, Tuot S, Chhoun P, Shibanuma A, Yasuoka J, et al. What are the factors associated with depressive symptoms among orphans and vulnerable children in Cambodia? BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:178. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0576-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Liew J, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, et al. Longitudinal relations of children's effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Dev Psychol. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumakech E, Cantor-Graae E, Maling S, Bajunirwe F. Peer-group support intervention improves the psychosocial well-being of AIDS orphans: Cluster randomized trial. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1038–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher PA, Gunnar MR, Dozier M, Bruce J, Pears KC. Effects of therapeutic interventions for foster children on behavioral problems, caregiver attachment, and stress regulatory neural systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:215–25. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raposa EB, Laws HB, Ansell EB. Prosocial behavior mitigates the negative effects of stress in everyday life. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4:691–8. doi: 10.1177/2167702615611073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martela F, Ryan RM. Prosocial behavior increases well-being and vitality even without contact with the beneficiary: Causal and behavioral evidence. Motiv Emot. 2016;40:351–7. [Google Scholar]