Abstract

Objective

Mental health care integrated into obstetric settings improves access to perinatal depression treatments. Digital interactions such as text messaging between patient and provider can further improve access. We describe the use of text messaging within a perinatal Collaborative Care(CC) program, and explore the association of text messaging content with perinatal depression outcomes.

Methods

We analyzed data from an open treatment trial of perinatal CC in a rural obstetric clinic. Twenty five women with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score of ≥10 enrolled in CC, and used text messaging to communicate with their Care Manager(CM). We assessed acceptability of text messaging with surveys and focus groups. We calculated the number of text messages exchanged, and analyzed content to understand usage patterns. We explored association between text messaging content and depression outcomes.

Results

CMs initiated 85.4% messages, and patients responded to 86.9% messages. CMs used text messaging for appointment reminders, and patients used it to obtain obstetric and parenting information. CMs had concerns about the likelihood of boundary violations. Patients appreciated the asynchronous nature of text messaging.

Conclusion

Text messaging is feasible and acceptable within a perinatal CC program. We need further research into the effectiveness of text messaging content, and response protocols.

Keywords: perinatal depression, collaborative care, text messaging

1. Introduction

Every year, 10 to 20% of women screen positive for depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period (perinatal depression).[1] Less than one third of these women receive adequate treatment for perinatal depression.[2] Several factors, especially relevant in the perinatal period, such as childcare needs, travel and stigma[3] contribute to poor treatment initiation and completion rates. Integrating mental health care delivery with perinatal care is one potential way to improve access and leads to improved retention rates and improved treatment outcomes.[4] Obtaining mental health care as part of prenatal care is acceptable to women[5] and can simultaneously address multiple barriers to care such as stigma and transportation. Digital encounterless and asynchronous interactions such as text messaging can complement and enhance integrated mental health care delivery systems[6] and can also address barriers such as transportation and stigma.[7] Text messaging can be human, computer based or hybrid.[8] In hybrid text messaging systems, a computer facilitates bulk sending of messages, and a human reads and responds to patient’s replies.[8]

While rigorous evaluation of text messaging programs is lacking, some have demonstrated improved antenatal care attendance.[9, 10] In the United States, automated messaging systems such as Text4Baby which deliver scheduled text messages to pregnant and postpartum women aim to promote a broad range of maternal and child health behaviors.[11]

Text messaging has also been used as an adjunct to mental health treatments, such as cognitive behavior therapy,[12] and to support medication adherence in individuals with psychotic disorders.[13] However, there is a dearth of reports of text messaging used as an adjunct in perinatal mental health treatments.[7] Furthermore, reports of text messaging in the literature are often limited to programmatic evaluations and do not always consider health outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first description of the use of text messaging in collaborative care for perinatal depression examining feasibility, acceptability, and association of text messaging content with depression outcomes.

In this analysis of data from an open treatment trial of perinatal Collaborative Care in a rural obstetric clinic, we aimed to: (1) Describe patients’ and Care Manager’s (CM’s) messaging behavior in terms of frequency of use and content; (2) Explore the association of text messaging content with depression outcomes; and (3) Conduct a qualitative analysis of patients and CM’s experiences of use of text messaging in perinatal depression treatment.

2. Methods

We conducted this analysis on data obtained from an open treatment trial of perinatal Collaborative Care in a rural obstetric clinic. Details of the trial have been previously described.[5] From October 2015 through March 2016, we enrolled into Collaborative Care 27 pregnant or postpartum women from an ethnically diverse population, based on meeting eligibility criteria of positive screen for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire – 9[14] - PHQ-9 score 10 or greater), English speaking, and 18 years and older. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington approved all study procedures. Three CMs were trained in an engagement session (manualized), Problem Solving Therapy (PST), text messaging protocols, and general information on perinatal mental health and pharmacotherapy. The CMs met with patients in the obstetric clinic or in the patients’ home and provided six to eight weekly sessions of PST, if chosen by the patient. CMs participated in weekly consultation calls with the study psychiatrist (AB) in which they discussed the CM’s caseload and received treatment recommendations to implement or convey to the patient’s Obstetrician.

2.1 Text messaging communication protocol

Between sessions, CMs communicated with patients via text messaging. CMs used text messaging to send appointment reminders and information about depression, antidepressants and parenting. We provided CMs with semi-structured guidelines for the content of text messages, but encouraged them to be responsive to the unique needs of their patients with regard to frequency and follow up of text messages. No formal treatment was provided by text messaging but the content did include reminders about PST homework and behavioral activation. CMs also told patients that they could initiate text messages at any time with their CM, informed patients that they would be able to respond to messages only during working hours, and gave patients frequent reminders that this number was not an appropriate number to contact in case of emergency. CMs also emphasized that the CM phones were password protected and not shared, and that patients should use similar caution due to limits to confidentiality of text message exchanges. CMs uploaded the messages to a Microsoft Excel workbook and then deleted them from their phones.

2.2 Measures

We measured PHQ-9 scores at baseline, study end, and at every CM visit over an average treatment time of 14.4 weeks (SD 4.8, range 5.7 to 23.1). Twenty five patients had at least two recorded PHQ–9 scores. We collected information on number and content of text messages sent and received for the duration of the study.

2.3 Survey (patients) and Focus groups (patients and CMs)

All patients who completed the study were given a 22 question survey regarding their experiences with the CC intervention, and suggestions for improvement. Five questions in the survey pertained to text messaging – Did you use text messaging to communicate with your CM?; Did you find it helpful?; What did you use text messaging for the most? Did you feel comfortable discussing personal information via text messaging?; and Would you feel comfortable sharing the content of your text messages with your partner or spouse? The survey included a question asking about interest in focus group participation. We conducted two patient focus groups with six and three participants each, to include all nine patients who indicated that they wanted to participate in a focus group. An experienced investigator independent of the study team facilitated the 90-minute focus groups using an interview guide. The focus groups were designed to elicit details of patients’ experiences in the study, with specific questions regarding their usage of text messaging. Examples of questions included in the interview guide included “How was communicating by text different from communicating by phone or in person? Which did you prefer? What kinds of messages were most helpful?” Participants received a $50 gift card at the end of the focus group. In the focus groups, we used open-ended probes informed by a literature review, to elicit participants’ opinions regarding treating perinatal depression in an obstetric clinic. We also conducted an end of study focus group among the three CMs. The focus group for the CMs was conducted by the same investigator who conducted the patient focus group using similar questions, and lasted for 90 minutes. We recorded, transcribed and checked the focus groups for accuracy.

3. Data analysis

3.1 Text messages

We summarized patient demographics and survey results using descriptive statistics. We calculated the total number of text messages each CM and patient sent and received.

We had access to the time stamped text message communications between CMs and their patients throughout the trial. AB and JM coded these text messages. We began by reading the text message transcripts line by line, and coding each text message exchange. We used a combination of a priori coding (based on our knowledge of what the CMs used text messaging for), and emergent coding. We developed a codebook (available on request) with definitions and coding rules. We used Microsoft Excel as our primary data analysis tool for the text messaging analysis, to record the codes assigned to the text messages.

1) We used a pilot coding period to refine our code book. In this pilot coding period, we used text messages from all 27 patients enrolled in the trial. We assigned codes to the first text message in every text message exchange between patient and CM. We defined a text message exchange as an interchange of text messages (initiated by either CM or patient) that was continuous with regard to content. Each exchange contained between 1 (a text message with no response) and 18 (an exchange regarding prescription drug use during breastfeeding) individual text messages, and was spread over a period of two to three days. This supported asynchronous but content continuous communication.[13] There were 502 exchanges in total. In this first round of coding, AB and JM both assigned codes to 29.7% (149/502) of the text message exchanges, compared codes, resolved differences through discussion, and achieved 90% agreement on codes. At each discussion, we further refined the codebook, identifying conceptual categories within the text messages, and modifying definitions of codes where necessary. We used constant comparisons throughout the process.[15] We then separately assigned codes to the remaining 70.3% (353/502) text message exchanges, meeting regularly to discuss the process and resolve coding discrepancies through consensus. Through this process, we assigned codes to all 502 text message exchanges from the duration of the trial.

For further analyses, we used data only from 25 patients for whom we had more than one PHQ-9 measurement, i.e., we excluded two patients who dropped out after baseline assessment.

We calculated percentages for all CM and patient codes and organized codes by themes and subthemes using thematic content analysis. We used simple logistic regression to examine the association of different text message codes with 50% improvement in depression score (defined as reduction in PHQ-9 score by at least 50% from baseline to study end).

3.2 Focus groups (patients and CMs)

We analyzed patient and CM focus groups using thematic content analysis in qualitative analysis software Atlas.ti Version X (2016) Berlin, Scientific Software Development (http://atlasti.com/), with both within group and between group comparisons.

4. Results

4.1 Survey results

Seventeen women completed the survey at the end of the study. All of them reported using text messages to communicate with their CM. Ninety four percent (n=16) of them found it helpful. In a “choose all that apply” question regarding usage, a majority of the women reported using text messaging most frequently for scheduling or rescheduling appointments (88%, n=15). Patients also used text messaging for questions about problem solving therapy homework (24%, n = 4), questions about depression or anxiety symptoms (24%, n= 4), questions about medications (12%, n= 2) and questions about physical symptoms (12%, n =2). Ninety four percent (n=16) of the women surveyed felt comfortable discussing personal information via text messaging, and 88% (n=15) said they felt comfortable sharing the content of the text messages with their partner or spouse.

4.2 Text messaging frequency and content

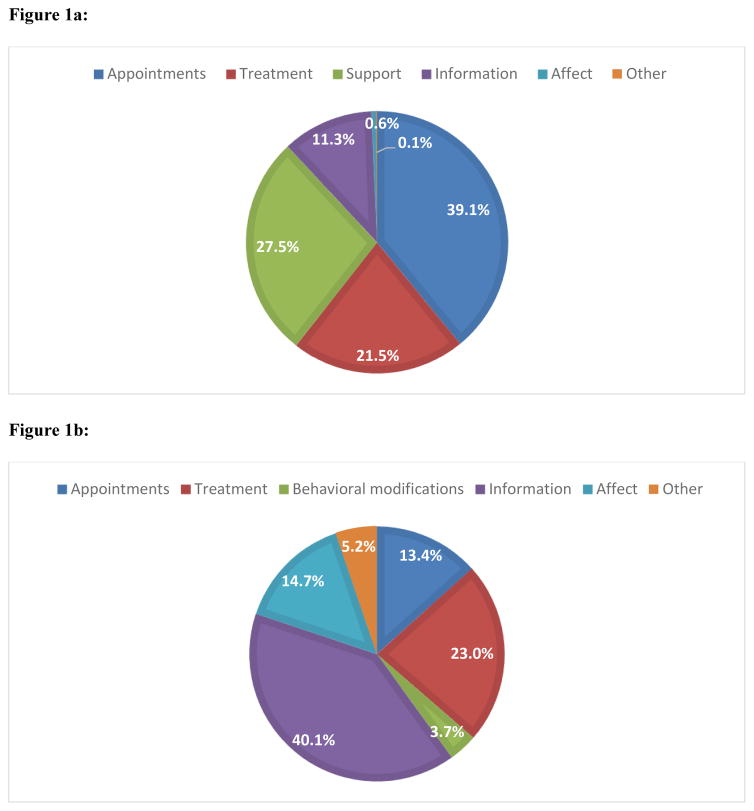

We report on data for 25 patients who completed more than one assessment. CMs sent a total of 1127 text messages, and patients sent a total of 862 text messages over the course of the study. Patients responded to 86.9% (771/888) of CM text messages. Each text message could contain one or more “codes” or themes (a total of 888 codes were identified within CM messages, and a total of 382 for patient messages). We found that CMs most frequently used text messaging for appointment reminders and “check-ins” (39.1%; 347/888), followed by supportive text messages (validation, encouragement and encouraging simple behavioral modifications) (27.5%; 244/888). Patients most frequently used text messages to discuss information (parenting, obstetric information) (40.1%; 153/382), treatment (23.0%; 88/382), and to describe how they were feeling (14.7%; 56/382) (Figure 1). (See Tables 1 and 2 for CM and patient text messaging themes and examples). Over the course of the study period, there were a total of 494 text message exchanges, of which CMs initiated 422 exchanges (85.4%) and patients initiated 72 exchanges (14.6%).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a: Care Manager initiated content themes (n= 888)

1b : Patient initiated content themes (n=382)

Table 1.

Care Manager text messaging content themes, categories, definitions and examples

| Themes | Categories | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appointments | Reminder |

|

“Just a reminder we are scheduled to meet at 9 am today. Let me know if anything comes up. Otherwise I will see you soon” |

| Check-in |

|

“Checking in to see how you are doing. Would it be okay if I call you on Friday morning to see how things are going with your medication and to do the depression screen?” | |

| Treatment | Depression |

|

“How is your sleep? How many hours are you getting a night.” |

| Medication |

|

“The doctor said you can definitely try Wellbutrin and it can increase energy but it is important to know that Wellbutrin can also increase anxiety.” | |

| Problem Solving Therapy |

|

“If you can do something for yourself each day that brings you joy, it will help to break the downward spiral of depression. Even something small, whatever that may be for you, taking a walk, having time with a friend.” | |

| Support | Behavioral modifications |

|

“NEST: nutrition, exercise, sleep, time to self!” |

| Validation |

|

“I know this is hard for you and you are doing a good job helping yourself through this. I support you trying this without medication. I'll check in on you again tomorrow” | |

| Encouragement |

|

“Great job for doing it even though you are sick!” (referring to a patient doing their PST homework) | |

| Information | Depression information |

|

“Sleep and emotional health are so closely intertwined - try your best to get good rest!” “How are you feeling? I hope you have been able to enjoy some of the sunshine we've had in these last few days. Exposure to bright light is so helpful for mood.” |

| Parenting |

|

“They will give you a list of childcare options that fit your criteria (area you want, take newborns, and any other preferences you have). When you call, let them know you are looking for child care for your newborn. they will probably ask you some questions. If you have any more questions, or problems with it when you call. Let me know and I'll help if I can.” | |

| Obstetric information |

|

“How did everything go with the birth? Breastfeeding? Let me know how I can support you.” | |

| Other information | “Yes, the prenatal yoga classes are at that same location and are taught by the greatest teacher. I think you would like it! And it's a great way to connect with other pregnant moms.” | ||

| Affect / Emotion Probes |

|

“The steps you came up with sound like they were successful in those days you accomplished your goal. So kudos to you! Glad to hear you have been feeling better! Have you been able to reflect on what has led to an improved mood?” | |

| Other | Gratitude |

|

N/A |

| Self-reported PHQ-9 scores |

|

N/A | |

| Side effects |

|

“Are you still having zingy feeling? If so does it come and go or is it constant? Any weakness in face with ziny feeling? Or do you just feel it on tongue?” | |

| Suicidal ideation |

|

N/A | |

| Other miscellaneous comment |

|

N/A |

Table 2.

Patient text messaging content themes, and examples:

| Themes | Categories | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Appointments | Reminder | “I totally thought today was Wednesday. I went to the clinic and realized it was only Tuesday. Baby brain at its best.” |

| Check-in | N/A | |

| Treatment | Depression | “Yes, I have gone for my walk but just feeling the same way wanting to cry and just feeling in the blue but I have to get through this no matter what” |

| Medication | “Hi, thanks for checking. I discontinued Effexor (last dose Monday) because I was feeling so ill and it was interfering with being able to take care of kids and eating enough for milk production. Still feeling some guilt about it (and residual nausea) but also feeling confident that was right choice for the present. Looking forward to meeting tomorrow.” | |

| Problem Solving Therapy | “Liking that goals were broken down into small, specific tasks. Working on building enthusiasm towards exercising. Framing it with overall goal of improving body image is helping with motivation, as well as reminding myself I'm building a skill. Good progress in that regard!” | |

| Behavioral modifications | Behavioral modifications | “Morning! Planning to walk with a friend later today! Hooray for sunshine. Thanks for checking in!” |

| Parenting | “[Child’s name] has been extremely fussy and nothing I do is soothing her and that's been pretty rough on me today :/” | |

| Obstetric information | “I had a Non-Stress Test yesterday and was contracting back to back. Cervix is a bit dilated and got shorter, the fetal fibronectin test came back positive and I have to go it to get it done again to see if it comes back negative and get another dose of the shot that helps baby's lung mature faster.” | |

| Other information | “Were doing really good. I'm gonna talk to my doctor when I go in to see him next week and ask him what I can do and take to quit smoking all the way” | |

| Affect / Emotion Probes | “Been struggling a bit. Feeling really moody and just having a hard time dealing with disappointments.” | |

| Other | Gratitude | “I've really appreciated having someone to talk to through all this and value your advice and sometimes it's just nice to have someone to vent to:)” |

| Self-reported PHQ-9 scores | “And here are my answers... #1–2, 1, 3, 3, 1,1, 2, 0, 0” | |

| Suicidal ideation | “We still meeting at 4:30 tomorrow?? Feeling suicidal this last week. It's just a constant struggle. I'm forcing a smile and hugging my kids because they are what keeps me alive. Feel like I can only talk to you about it. Don't feel safe talking to my husband about it.” | |

| Other miscellaneous comment | “[Friend] is going to Alcoholics Anonymous so everything is going really awesome.” |

One patient expressed suicidal ideation via text message. The CM was able to respond to her message in a timely manner and encourage her to seek emergency care.

4.3 Association of text messaging content with depression outcomes

As reported elsewhere,[5] at study end, 64% of patients (n=16) had 50% or more decrease in their PHQ-9 score. We conducted exploratory analyses of association of text messaging content themes and 50% improvement in PHQ–9 score, controlling for total number of CM messages and did not find any significant association (for appointment reminder texts, Wald χ2 = 0.036, df = 1, p= 0.85; for text messages about treatment, Wald χ2 = 1.393, df = 1, p= 0.24; for supportive text messages, Wald χ2 = 0.619, df = 1, p= 0.43; for text messages with information, Wald χ2 = 0.262, df = 1, p= 0.61).

4.4 Post hoc analysis of association of text messaging content with attendance at appointments

Given that CMs most frequently used text messaging for appointment reminders, we explored whether receiving such appointment reminder messages actually translated into attendance at appointments. In a linear regression we found that appointment reminder texts sent by the CM were significantly associated with number of appointments kept (β = 0.502, R2 = 0.219, p=0.011). However, on controlling for total number of CM messages, the association was no longer statistically significant (β = 0.011, R2 = 0.255, p=0.977)

4.5 Care Manager and Patient Focus group content (Table 3)

Table 3.

Focus group themes and examples:

| Boundaries | |

|---|---|

| CMs perceived that text messaging was not conducive to maintaining work–life boundaries. |

|

| Patients appreciated CM’s availability outside of office hours, and were disappointed when they did not get a response to their messages. |

|

| CMs perceived that text messaging made it more difficult for them to define their boundaries as providers |

|

| Both CMs and patients perceived that text messages were helpful as they communicated CM’s participation in patient care even outside of in person sessions |

|

|

Effectiveness Flexibility, Accessibility | |

| Patients found the asynchronous nature of text messaging particularly useful, especially given their multiple competing priorities |

|

| Patients also appreciated the asynchronous nature of text messages for other reasons |

|

| Some women, especially those who were receiving automated text messages from other services, found it difficult to differentiate the sources of the text messages. |

|

CMs experienced some challenges in the use of text messaging, such as maintaining boundaries – both in terms of defining limits to the work day, and setting interpersonal boundaries with their patients. They remarked that text messaging is usually considered a means to communicate with friends and this increases the likelihood of boundary violations when using text messages to communicate with a health care provider. Patients, on the other hand, greatly appreciated the CM’s availability for text messages in between appointments and after. Patients found the availability between appointments and asynchronous nature of text messages particularly useful as they had multiple competing priorities such as childcare. Focus group findings corroborated our analysis of content themes, in that CMs reported using text messages to remind patients about interventions and for appointment reminders.

5. Discussion

In this study of text messaging usage by CMs and patients in a perinatal collaborative care program, we found that both patients and CMs found text messaging acceptable and useful as an adjunct to regular in person sessions. Previous studies found that 96% of women have a favorable attitude toward receiving text messages about prenatal care[9] and our qualitative work reported here on attitudes to receiving text messages during perinatal depression treatment found similar high levels of interest.

Patients responded to CM initiated text messages at a high rate of 86.9%. They initiated text messages less frequently than CMs, at 14.6% of total text message exchanges. Previous studies report each participant sending 0.46 messages per week over 7 to 8 months of antenatal care[8] In our study, the mean number of patient initiated text messages was 2.9 over a mean of 14.6 weeks in treatment. Larger studies are needed to investigate whether text message initiation and response rates can be used as a metric of engagement in care.

Although we provided preliminary guidance on suggested content for text messages, CMs included additional topics in their text messages. In addition to behavioral activation and medication reminders and depression information, CMs also used text messages frequently for appointment reminders, validation, encouragement, and obstetric and parenting information. On the survey, patients reported using text messages most frequently for scheduling and rescheduling appointments, perhaps reflecting their response to CM appointment reminders. However, content analysis results suggest that when patients initiated a text message exchange, they most frequently used it to obtain information, discuss medications, and report how they were feeling (both psychiatric and obstetric symptoms). Text messages with informational content can decrease anxiety in the perinatal period.[16] However, CMs were frequently called upon by patients to answer text message questions about topics on which they had no formal training (such as obstetric information and parenting ). It is therefore important to have in place systems for supervision of this content, or a protocol to address questions that may fall outside a CM’s zone of expertise.[13]

We did not find a significant association between any one type of text message content and depression improvement. It is possible that this was due to the small sample size and it is worth examining this issue further in a larger study, to inform the content of text messages that correlates most strongly with depression improvement. Our post hoc analysis did not find an association between appointment reminder text messages and attendance at appointments, after controlling for total number of text messages. Although reminder texts can increase attendance at appointments,[17] previous reports are based on automated text messaging services. In the context of customized text messages with varying content, it is possible that the salience of an appointment reminder text is lost. This underlines the need for further study of the most effective content for text messages when examining association with outcomes such as appointment attendance and depression improvement.

Patients particularly welcomed the asynchronous nature of text messaging, and the ability to get some of their health care needs met in between appointments. Unique challenges of the perinatal period such as childcare and transportation were reasons cited for appreciating the flexibility and accessibility of text messaging. Our text messaging protocol clearly stated that text messaging was only for use on weekdays and during working hours, but this boundary was not maintained by either the CMs or the patients. Two-way text messaging protocols in the treatment of perinatal depression should take into account time spent by CMs on text messaging activities and emphasize the need to maintain boundaries. Hybrid systems are one way to scale up text messaging without increasing burden on CMs.[8]

There was some concern that women who received automated messages from other services could not distinguish the source of text messages, but overall the women preferred messages they perceived as being sent by a human as opposed to being computer generated. Although an analysis of Text4baby data found that higher levels of text message exposure predicted favorable behavior change in terms of lower self-reported alcohol consumption,[18] our qualitative analysis suggested that women tended to ignore frequent messages from an automated service.

5.1 Potential limitations of using TM in perinatal depression care

Potential unintended harms of automated text messaging systems include women misinterpreting the information in texts, or relying solely on text message information from the CM as a substitute for a visit to a healthcare providers.[19] Women with mental health issues may use text messaging for communication of suicidal ideation. Without an appropriate protocol in place, this could lead to delayed response in crisis situations. Unlike systematic crisis response text messaging systems,[20] many health care systems which choose to use two way text messages to communicate with their patients may not be equipped to deal with an emergency situation. In our study, despite frequent reminders to patients that they should not text message their CM in an emergency situation, one patient texted a CM about her suicidal ideation. An adverse outcome was averted in this case but this highlights the risks and potential responsibilities associated with two-way messaging systems. There is clearly a need to delineate response protocols before two way messaging is rolled out in a systematic way in perinatal depression treatments.

Another consideration is that of confidentiality and of health information security. Federal laws do not rule out sending protected health information via text messages.[21] However, any text message which is personalized and responsive to a patient’s unique mental health circumstances, if discovered by unauthorized individuals, risks disclosing protected health information. This could be addressed by using generic, rather than customized messages. However, generic messages, unlike tailored messages, may not lead to engagement in care and behavior change.[22] There is clearly a need for further clear guidance on health information security in the use of text messaging as a digital asynchronous communication between patient and health care provider.[23]

5.2 Limitations of our study

The survey questionnaire we used was designed specifically for this study and is not a validated questionnaire. We did not have the statistical power to adequately examine the association of text messaging frequency or content with depression outcomes. As text messaging was a supplement to the main intervention (perinatal collaborative care), it is difficult to separate out the relative effect of each individual treatment component.

5.3 Conclusions

Text messaging is an acceptable and feasible means of digital synchronous or asynchronous communication between CMs and patients being treated for perinatal depression.

Digital asynchronous communication such as text messaging can improve access to health care [6] especially given the fact that rates of texting are higher among traditionally underserved populations such as racial and ethnic minorities, and low income populations.[24] Particularly in the perinatal population, with multiple barriers to access, text messaging can serve as a useful adjunct to mental health treatment delivery. However, there is a need for clear guidelines surrounding extent of use, use in emergencies and security of data. Future research should evaluate the impact of hybrid systems which can increase the capacity of CMs by combining: 1) the automated sending of personalized messages to patients with 2) the CM’s ability to respond to specific questions or requests from patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: DAWN was funded by R01 MH085668, PI Unützer.

At the time of this study, Amritha Bhat was a postdoctoral fellow in the NIMH 537 T32 MH20021 Psychiatry-Primary Care Fellowship Program Training Grant.

The funding source had no role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

The authors would like to thank Erin McCoy, MPH for conducting the focus groups and Theresa Hoeft for supporting the qualitative analysis of focus groups. We also extend our gratitude to the patients, care managers and prenatal care providers who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byatt N, Levin LL, Ziedonis D, Moore Simas TA, Allison J. Enhancing Participation in Depression Care in Outpatient Perinatal Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1048–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman JH. Women’s Attitudes, Preferences, and Perceived Barriers to Treatment for Perinatal Depression. Birth. 2009;36:60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E, et al. Collaborative Care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: a randomized trial. Depression and anxiety. 2015;32:821–834. doi: 10.1002/da.22405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat A, Reed S, Mao J, Vredevoogd M, Russo J, Unger J, et al. Delivering perinatal depression care in a rural obstetric setting: a mixed methods study of feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017 doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2017.1367381. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortney JC, Burgess JF, Jr, Bosworth HB, Booth BM, Kaboli PJ. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011;26:639–647. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1806-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broom MA, Ladley AS, Rhyne EA, Halloran DR. Feasibility and perception of using text messages as an adjunct therapy for low-income, minority mothers with postpartum depression. JMIR mental health. 2015:2. doi: 10.2196/mental.4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrier T, Dell N, DeRenzi B, Anderson R, Kinuthia J, Unger J, et al. Engaging Pregnant Women in Kenya with a Hybrid Computer-Human SMS Communication System. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM; 2015; pp. 1429–1438. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormick G, Kim NA, Rodgers A, Gibbons L, Buekens PM, Belizán JM, et al. Interest of pregnant women in the use of SMS (short message service) text messages for the improvement of perinatal and postnatal care. Reproductive health. 2012;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lund S, Hemed M, Nielsen BB, Said A, Said K, Makungu M, et al. Mobile phones as a health communication tool to improve skilled attendance at delivery in Zanzibar: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2012;119:1256–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans WD, Wallace JL, Snider J. Pilot evaluation of the text4baby mobile health program. BMC public health. 2012;12:1031. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilera A, Muñoz RF. Text Messaging as an Adjunct to CBT in Low-Income Populations: A Usability and Feasibility Pilot Study. Professional psychology, research and practice. 2011;42:472–478. doi: 10.1037/a0025499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aschbrenner KA, Naslund JA, Gill LE, Bartels SJ, Ben-Zeev D. A Qualitative Study of Client–Clinician Text Exchanges in a Mobile Health Intervention for Individuals With Psychotic Disorders and Substance Use. Journal of dual diagnosis. 2016;12:63–71. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2016.1145312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric annals. 2002;32:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jareethum R, Titapant V, Tienthai C, Viboonchart S, Chuenwattana P, Chatchainoppakhun J. Satisfaction of healthy pregnant women receiving short message service via mobile phone for prenatal support: A randomized controlled trial. Medical journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2008;91:458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasvold PE, Wootton R. Use of telephone and SMS reminders to improve attendance at hospital appointments: a systematic review. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2011;17:358–364. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.110707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans W, Nielsen PE, Szekely DR, Bihm JW, Murray EA, Snider J, et al. Dose-Response Effects of the Text4baby Mobile Health Program: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2015;3:e12. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Velthoven MH, Majeed A, Car J. Text4baby - national scale up of an mHealth programme. Who benefits? J R Soc Med. 2012;105:452–3. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.120176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crisis Text Line. 2017.

- 21.Drolet B. Text messaging and protected health information: What is permitted? JAMA. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009;36:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karasz HN, Eiden A, Bogan S. Text messaging to communicate with public health audiences: how the HIPAA Security Rule affects practice. American journal of public health. 2013;103:617–622. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith A. Americans and text messaging. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]