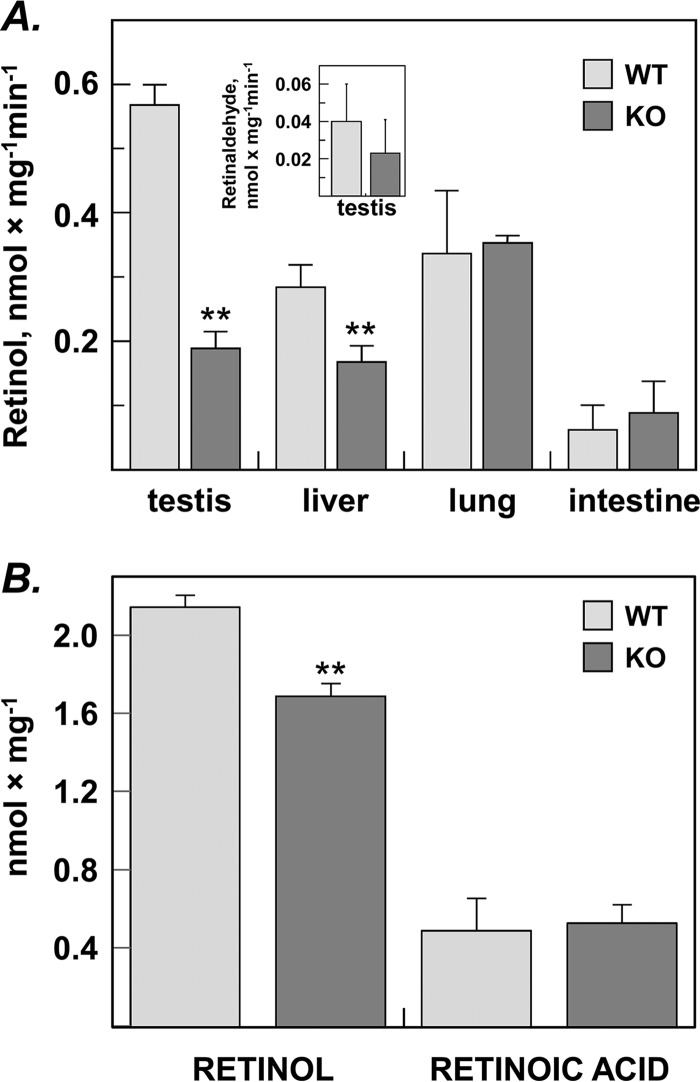

Figure 3.

Analysis of the retinaldehyde reductase activity in tissues of RDH11 knockout (KO) mice versus wildtype (WT) littermates. A, the reduction of all-trans–retinaldehyde to all-trans–retinol by tissue microsomal fractions. Microsomes from testis (10 μg), liver (6 μg), lung (10 μg), and intestine (60 μg) were incubated with retinaldehyde (0.5 μm) and NADPH (1 mm) for 15 min, and the products of retinaldehyde metabolism were analyzed by normal-phase HPLC. Values represent mean ± S.D. of samples from three individual animals; **, p < 0.001. Inset, because testis microsomes showed the greatest difference in the rate of retinaldehyde reduction to retinol between WT and KO mice, testes microsomes (40 μg) were also incubated with all-trans–retinol (10 μm) in the presence of NAD+ (1 mm) to assess their retinol dehydrogenase activity. Note that the rate of retinol oxidation was ∼10-fold lower than the rate of retinaldehyde reduction, and there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.28) between the rates of WT microsomes (0.039 ± 0.019 nmol × min−1 × mg−1, n = 5) versus KO microsomes (0.022 ± 0.018 nmol × min−1 × mg−1, n = 3). B, metabolism of retinaldehyde in living MEFs isolated from RDH11-null or WT mouse embryos. Freshly prepared E14.5 MEFs were seeded into 6-well plates and allowed to attach. On the next day, the cells were incubated with 5 μm all-trans–retinaldehyde for 1.5 h, and harvested for normal-phase HPLC analysis. Values represent mean ± S.D. of samples from three individual animals each performed in triplicates; **, p = 0.0009.