Abstract

Dna2 is a nuclease and helicase that functions redundantly with other proteins in Okazaki fragment processing, double-strand break resection, and checkpoint kinase activation. Dna2 is an essential enzyme, required for yeast and mammalian cell viability. Here, we report that numerous mutations affecting the DNA damage checkpoint suppress dna2∆ lethality in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. dna2∆ cells are also suppressed by deletion of helicases PIF1 and MPH1, and by deletion of POL32, a subunit of DNA polymerase δ. All dna2∆ cells are temperature sensitive, have telomere length defects, and low levels of telomeric 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). Interestingly, Rfa1, a subunit of the major ssDNA binding protein RPA, and the telomere-specific ssDNA binding protein Cdc13, often colocalize in dna2∆ cells. This suggests that telomeric defects often occur in dna2∆ cells. There are several plausible explanations for why the most critical function of Dna2 is at telomeres. Telomeres modulate the DNA damage response at chromosome ends, inhibiting resection, ligation, and cell-cycle arrest. We suggest that Dna2 nuclease activity contributes to modulating the DNA damage response at telomeres by removing telomeric C-rich ssDNA and thus preventing checkpoint activation.

Keywords: Dna2, telomere, yeast

THE conserved nuclease/helicase Dna2 affects 5′ processing of Okazaki fragments during lagging strand replication (Budd and Campbell 1997), resection of double-strand breaks (DSBs)/uncapped telomeres (Ngo et al. 2014), activation of DNA damage checkpoint pathways (Kumar and Burgers 2013), resolution of G quadruplexes (Lin et al. 2013), and mitochondrial function (Budd et al. 2006; Duxin et al. 2009). Increased expression of DNA2 is found in a broad spectrum of cancers, including leukemia, melanoma, breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, and colon cancers (Peng et al. 2012; Dominguez-Valentin et al. 2013; Strauss et al. 2014; Jia et al. 2017; Kumar et al. 2017; Wellcome Sanger Institute). Dna2 is an important enzyme because its loss is lethal in human cell lines, mice, Caenorhabditis elegans, budding yeast, and fission yeast (Budd et al. 1995; Kang et al. 2000; Lin et al. 2013). The amount of Dna2 in cells also seems to be important as dna2∆/DNA2 heterozygous mice show increased levels of aneuploidy-associated cancers and cells from these mice contain high numbers of anaphase bridges and dysfunctional telomeres (Lin et al. 2013).

In budding yeast Dna2 functions redundantly with other proteins in its various roles and intriguingly, unlike Dna2, most of these proteins are not essential. For example, Rad27, Rnh201, and Exo1 are all nonessential and are also involved in processing of 5′ ends of Okazaki fragments (Bae et al. 2001; Kao and Bambara 2003). Exo1, Sgs1, Sae2, Mre11, Rad50, and Xrs2 are all nonessential and are involved in DSB resection (Mimitou and Symington 2008; Zhu et al. 2008; Shim et al. 2010). Ddc1 (nonessential) and Dpb11 (essential) are involved in Mec1 (essential) checkpoint kinase activation (Puddu et al. 2008; Navadgi-Patil and Burgers 2009a,b; Kumar and Burgers 2013). Given that Dna2 often functions redundantly with nonessential proteins, it is unclear what specific function or functions of Dna2 is/are so critical for cell viability.

Several genetic and biochemical experiments have suggested that the most critical function of Dna2 is in processing long flaps at a small subset of 5′ ends of Okazaki fragments (Budd et al. 2011; Balakrishnan and Bambara 2013). Dna2 is unique in that, unlike the other 5′ nucleases (Rad27, Exo1, Rnh201), it can cleave RPA-coated single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) (Stewart et al. 2008; Cejka et al. 2010; Levikova et al. 2013; Levikova and Cejka 2015; Myler et al. 2016). RPA, the major eukaryotic ssDNA binding protein, binds ssDNA of 20 bases or more (Sugiyama et al. 1997; Rossi and Bambara 2006; Balakrishnan and Bambara 2013). Furthermore, RPA-coated ssDNA is potentially lethal because it stimulates DNA damage checkpoint responses (Lee et al. 1998; Zou and Elledge 2003).

Two reported null suppressors of dna2∆ lethality, rad9∆ and pif1∆, delete proteins that interact with RPA-coated ssDNA (Budd et al. 2006, 2011). Rad9 is important for the checkpoint pathway stimulated by RPA-coated ssDNA (Lydall and Weinert 1995). Pif1, a 5′ to 3′ helicase, increases the length of 5′ ssDNA flaps on Okazaki fragments, creating substrates for RPA binding and therefore checkpoint activation and Dna2 cleavage (Pike et al. 2009; Levikova and Cejka 2015). These genetic and biochemical data supported a model in which Dna2 is critical for cleaving RPA-coated long flaps from a subset of Okazaki fragments (Budd et al. 2011). However, more recently it was reported that other checkpoint mutations (ddc1∆ or mec1∆) also affecting the response to RPA-coated ssDNA did not suppress dna2∆ (Kumar and Burgers 2013). It was suggested that specific interactions between Rad9 and Dna2 were important for the viability of dna2∆ rad9∆ cells, rather than the response to RPA-coated ssDNA per se (Kumar and Burgers 2013).

In budding yeast, checkpoint mutations such as rad9∆ and ddc1∆ exacerbate fitness defects caused by general DNA replication defects (e.g., defects in DNA ligase, Pol α, Pol ε, or Pol δ) (Weinert et al. 1994; Dubarry et al. 2015), but suppress defects caused by mutations affecting telomere function (e.g., defects in Cdc13, Stn1, Yku70) (Addinall et al. 2008; Holstein et al. 2017). The opposing effects of checkpoint mutations in general DNA replication or telomere-defective contexts is most likely explained by damage to noncoding telomeric DNA being comparatively benign in comparison to damage to coding DNA in the middle of chromosomes. By this logic, the suppression of dna2∆ by rad9∆ implies that dna2∆ might cause telomere-specific rather than general chromosome replication defects. Furthermore, Dna2 localizes to human and yeast telomeres (Choe et al. 2002; Chai et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2013), and pif1∆, which suppresses dna2∆, affects a helicase that is active at telomeres and affects telomere length (Dewar and Lydall 2010; Budd and Campbell 2013; Lin et al. 2013; Phillips et al. 2015). Thus, several lines of evidence suggest that Dna2 might play critical function(s) at telomeres.

To further explore whether Dna2 is important at telomeres, we set out to clarify the effects of checkpoint pathways on fitness of dna2∆ mutants. We find that deletion of numerous DNA damage checkpoint mutations, all affecting responses to RPA-coated ssDNA, as well as deletions of Pif1 and Mph1 helicases, and Pol32, a subunit of Pol δ, suppress dna2∆ to a similar extent. These findings, along with a number of other telomere phenotypes lead us to suggest that the most critical function of Dna2 for cell viability is at telomeres. There are three possible substrates for Dna2 activity at telomeres: unwound telomeres, long flaps on terminal telomeric Okazaki fragments, and G4 quadruplexes formed on the G-rich ssDNA. We propose that the critical function of Dna2 is removing RPA-coated, 5′ C-rich, ssDNA at telomeres.

Materials and Methods

Yeast culture and passage

All yeast strains were in W303 background and RAD5+ and ade2-1, except strains used for microscopy, which were ADE2. Strains and plasmids details are in Supplemental Material, Tables S1 and S2 in File S1, respectively. Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Media were prepared as described previously and standard genetic techniques were used to manipulate yeast strains (Sherman et al. 1986). YEPD (1 liter: 10 g yeast extract, 20 g bactopeptone, 50 ml 40% dextrose, 15 ml 0.5% adenine, 935 ml H2O) medium was generally used. Dissected spores were germinated for 10–11 days at 20°, 7 days at 23°, or 3–4 days at 30°. Colonies from spores on germination plates were initially, instead of patched onto YEPD medium plates and grown for 3 days. Next. these were streaked for single colonies and incubated for 3 days at 23°. Thereafter, 5–10 colonies of each strain were pooled by toothpick and streaked for single colonies every 3 days.

Yeast spot test assays

A total of 5–10 colonies were pooled, inoculated into 2 ml YEPD medium and grown to saturation on a wheel at 23°. Saturated cultures were fivefold serially diluted in sterile water (40:160 μl) in 96-well plates. Cultures were transferred onto rectangular YEPD medium agar plates with a rectangular pin tool, and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days before photography, unless stated otherwise.

In-gel assay/Southern blots

In-gel assays were performed as previously described (Dewar and Lydall 2012), with minor modifications. Infrared 5′ IRDye 800 probes were used (AC probe: M3157, CCCACCACACACACCCACACCC; TG probe: M4462, GGGTGTGGGTGTGTGTGGTGGG; Integrated DNA Technologies). No RNAse was used during nucleic acid purification. Samples were run on a 1% agarose gel in 0.5× TBE (50 V for 3 hr), and the probe was detected on a LI-COR (Odyssey) imaging system. ssDNA was quantified using ImageJ. The gel was then placed back in an electrophoresis tank, run for 2 hours, and processed for Southern blotting. Then, gel was stained using SYBR Safe, and DNA was detected using a Syngene’s G:BOX imaging system. DNA was then transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane. The membrane was hybridized with a 1 kbp Y′ and TG probe, as previously described (Holstein et al. 2014). Loading controls were generated by foreshortening the full-sized SYBR Safe-stained gel images with Adobe Illustrator CS6.

Yeast live-cell imaging

Cells were grown shaking in liquid synthetic complete medium supplemented with 100 µg/ml adenine at 25°, to OD600 = 0.2–0.3, and processed for fluorescence microscopy as described previously (Silva et al. 2012). Rfa1 was tagged with cyan fluorescent protein (clone W7) (Heim and Tsien 1996) and Cdc13 with yellow fluorescent protein (clone 10C) (Ormö et al. 1996; Khadaroo et al. 2009). Fluorophores were visualized with oil immersion on a widefield microscope (AxioImager Z1; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a 100× objective lens (Plan Apochromat, numerical aperture 1.4; Carl Zeiss), a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Orca-ER; Hamamatsu Photonics), DIC, and an illumination source (HXP120C; Carl Zeiss). Eleven optical sections with 0.4 µm spacing through the cell were imaged. Images were acquired and analyzed using Volocity software (PerkinElmer). Images were pseudocolored according to the approximate emission wavelength of the fluorophores.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. Table S1 in File S1 lists all strains.

Results

dna2∆ lethality is suppressed by checkpoint inactivation

To clarify the effect of DNA damage checkpoint gene deletions in dna2∆ cells, heterozygous dna2∆ checkpoint∆ diploid strains were sporulated, tetrads were dissected, and viable genotypes determined. We examined the effects of RAD9, DDC1, and MEC1, affecting a checkpoint mediator protein, a component of the 9-1-1 checkpoint sliding clamp, and the central checkpoint kinase (homolog of human ATR), respectively, and all previously studied in the context of dna2∆ (Budd et al. 2011; Kumar and Burgers 2013). We also examined RAD17, encoding a partner of Ddc1 in the checkpoint sliding clamp; CHK1, encoding a downstream checkpoint kinase; RAD53, a parallel downstream kinase; and TEL1, encoding the homolog of human ATM. As a positive control for suppression, we also examined the effects of PIF1, encoding a 5′ to 3′ helicase, because pif1∆ (like rad9∆) suppresses dna2∆ (Budd et al. 2006).

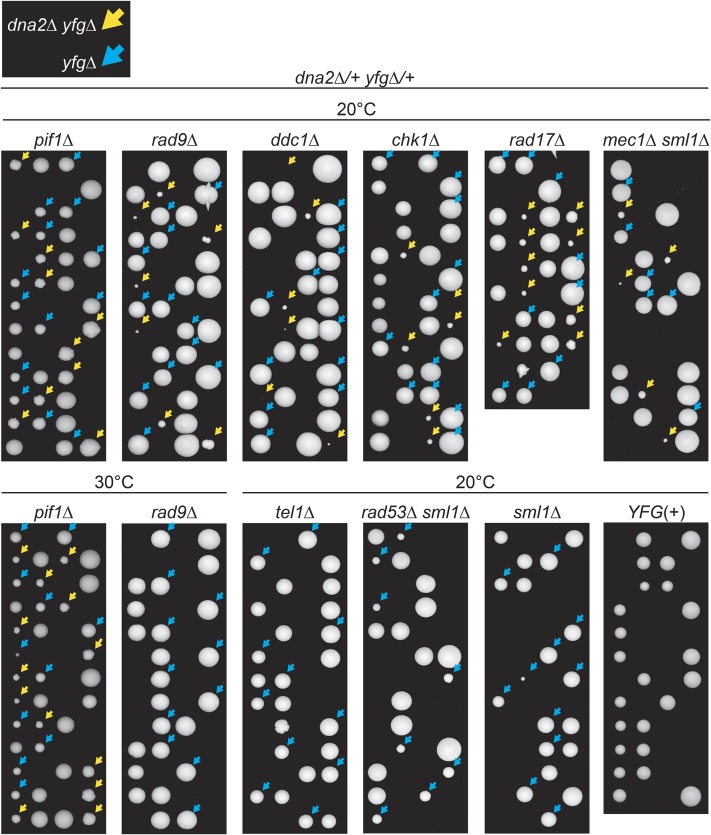

dna2∆ rad9∆ and dna2∆ pif1∆ strains are temperature sensitive (Budd et al. 2006, 2011) and therefore spores were germinated at 20, 23, and 30° to allow comparison of dna2∆ suppression frequencies at different temperatures. Interestingly, the effects of rad9∆, ddc1∆, rad17∆, chk1∆, and mec1∆ were very similar, as they each permitted dna2∆ strains to form colonies at 20 and 23° but not at 30° (Figure 1, Figure S1a in File S1, and Table 1). In comparison, pif1∆ suppressed dna2∆ with higher efficiency and at higher temperatures, and pif1∆ dna2∆ colonies on germination plates were larger than those permitted by checkpoint gene deletions (Figure 1, Figure S1a in File S1, and Table 1). tel1∆ and rad53∆ did not suppress dna2∆, presumably because they have different roles in the DNA damage response. We conclude that rad9∆, ddc1∆, rad17∆, chk1∆, and mec1∆, but not rad53∆ and tel1∆ checkpoint mutations, suppress inviability caused by dna2∆. These data suggest that dna2∆ causes lethal Rad9, Rad17, Ddc1, Chk1, and Mec1 mediated cell-cycle arrest. Given that checkpoint mutations suppress dna2∆ and telomere defects (cdc13-1, yku70∆, and stn1-13) (Addinall et al. 2008; Holstein et al. 2017) but enhance DNA replication defects (Weinert et al. 1994; Dubarry et al. 2015), the pattern of dna2∆ genetic interactions strongly suggests that dna2∆ cells contain telomere defects.

Figure 1.

Checkpoint mutations permit growth of dna2∆ cells at 20°. Diploids heterozygous for dna2∆ and pif1∆, rad9∆, ddc1∆, chk1∆, rad17∆, mec1∆ sml1∆, tel1∆, rad53∆ sml1∆ or sml1∆ mutations were sporulated, tetrads were dissected, and spores germinated. Germination plates were incubated for 10–11 days at 20°, or 3–4 days at 30°. Strains of dna2∆ yfg∆ background are indicated by yellow arrows, and strains of yfg∆ background are indicated by blue arrows. Additional images of growth at 20, 23, or 30° are in Figure S1 in File S1. Strains were as follows: DDY1285, DDY874, DDY876, DDY878, DDY880, DDY958, DDY950, DDY947, DDY952, and DDY1276. Strain details are in Table S1 in File S1.

Table 1. dna2∆ suppression efficiency.

| 20° | 23° | 30° | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viable dna2∆ xyz∆ | Expected dna2∆ xyz∆ | Viable dna2∆ xyz∆ | Expected dna2∆ xyz∆ | Viable dna2∆ xyz∆ | Expected dna2∆ xyz∆ | |

| XYZ | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | ||

| rad9∆ | 14 | 26 | 7 | 26 | 0 | 25 |

| ddc1∆ | 13 | 26 | 11 | 26 | 0 | 26 |

| rad17∆ | 20 | 23 | 12 | 26 | 0 | 25 |

| chk1∆ | 14 | 26 | 7 | 25 | 0 | 26 |

| mec1∆ sml1∆ | 16 | 49 | 0 | 12 | ||

| pif1∆ | 24 | 25 | 13 | 12 | ||

| mph1∆ | 10 | 26 | 0 | 13 | ||

| pol32∆ | 0 | 13 | 5 | 13 | 9 | 13 |

| rad53∆ sml1∆ | 0 | 19 | 0 | 25 | ||

| tel1∆ | 0 | 38 | 0 | 13 | ||

| sml1∆ | 0 | 13 | ||||

20, 23, and 30° are the temperatures at which spores were germinated. The leftmost column shows the gene deleted in each dna2∆/+ diploid. Viable dna2∆ xyz∆ is the number of spores that germinated and formed visible colonies. Expected dna2∆ xyz∆ is the expected number of viable dna2∆ xyz∆ strains if xyz∆ completely suppressed the dna2∆ inviable phenotype, based on the total number of tetrads dissected. For example, 25% of dna2∆/+ rad9∆/+ spores should be dna2∆ rad9∆, and 12.5% of mec1∆/+ sml1∆/+ dna2∆/+ should be mec1∆ sml1∆ dna2∆.

DNA2 deletion causes temperature sensitivity

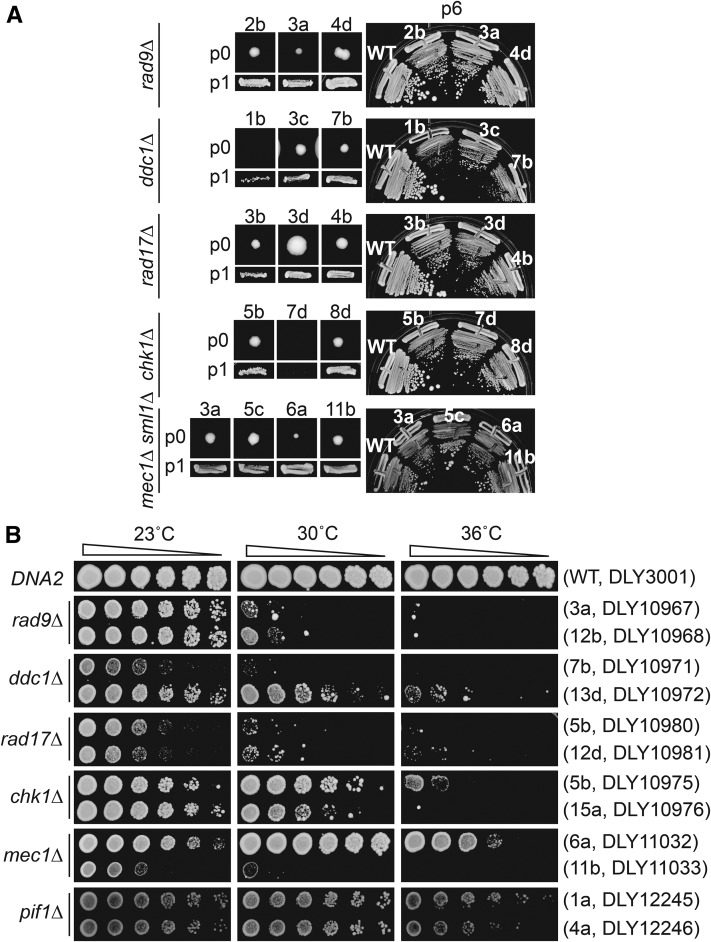

On germination plates dna2∆ checkpoint∆ colonies were often small and heterogeneous in size in comparison with dna2∆ pif1∆ colonies, implying that mutating checkpoint genes did not suppress the dna2∆ growth defects as efficiently as removing the Pif1 helicase (Figure 1). One explanation for this difference in colony size was that checkpoint mutations permitted only a limited number of cell divisions, but that ultimately the dna2∆ checkpoint∆ double-mutant clones would senesce and cease growth. To test this hypothesis, dna2∆ checkpoint∆ double mutants were passaged further. Interestingly, the opposite to senescence was observed, and dna2∆ checkpoint∆ mutants in fact became fitter and more homogeneous in colony size with passage and grew indefinitely (Figure 2A and Figure S2a in File S1). This suggests that dna2∆ checkpoint∆ double mutants originally grow quite poorly and that some type of adaptation to the absence of Dna2 occurs in dna2∆ checkpoint∆ mutants. We considered that additional suppressor mutations had arisen in dna2∆ checkpoint∆ mutants, but backcross experiments did not support this hypothesis (Figure S1b in File S1). It was also clear that even different strains of the same genotype became similarly fit when passaged at 23°, which is inconsistent with different suppressor mutations arising. However, all strains remained temperature sensitive for growth at higher temperatures, and growth at high temperature was more heterogeneous than growth at low temperature (Figure 2B and Figure S2b in File S1). Overall, passage of dna2∆ checkpoint∆ strains shows that they adapt to the absence of Dna2 but remain temperature sensitive for growth, presumably because ongoing cellular defects are more penetrant at higher temperature. Consistent with a previous study (Budd et al. 2006), dna2∆ pif1∆ strains, the least temperature-sensitive genotype, formed smaller colonies at 36° than at 30°, showing that even these cells also have a temperature-sensitive molecular defect (Figure 2B). We noted a similarity between yku70∆ and dna2∆ strains as each genotype exhibits a temperature-sensitive phenotype and is suppressed by checkpoint mutations (Maringele and Lydall 2002). In the case of yku70∆ mutants, high levels of 3′ ssDNA are generated at telomeres at high temperature (Maringele and Lydall 2002).

Figure 2.

dna2∆ strains improve growth with passage, but remain temperature sensitive. (A) Colonies of dna2∆ yfg∆ double mutants on germination plates (passage 0, p0) p1 (patched) and p6 (streaked) are shown. A single DNA2 (wild type; WT) is used for comparison at p6. (B) Spot test assays of strains at p6 (or p1 for pif1∆ dna2∆ strain). Strains of each genotype at each temperature were grown on single agar plates, but images have been cut and pasted to make comparisons easier. Original images are in Figure S2 in File S1. Each colony position on germination plates from Figure 1 and strain numbers are indicated. Strain details are in Table S1 in File S1.

dna2∆ cells have abnormal telomere length with limited ssDNA

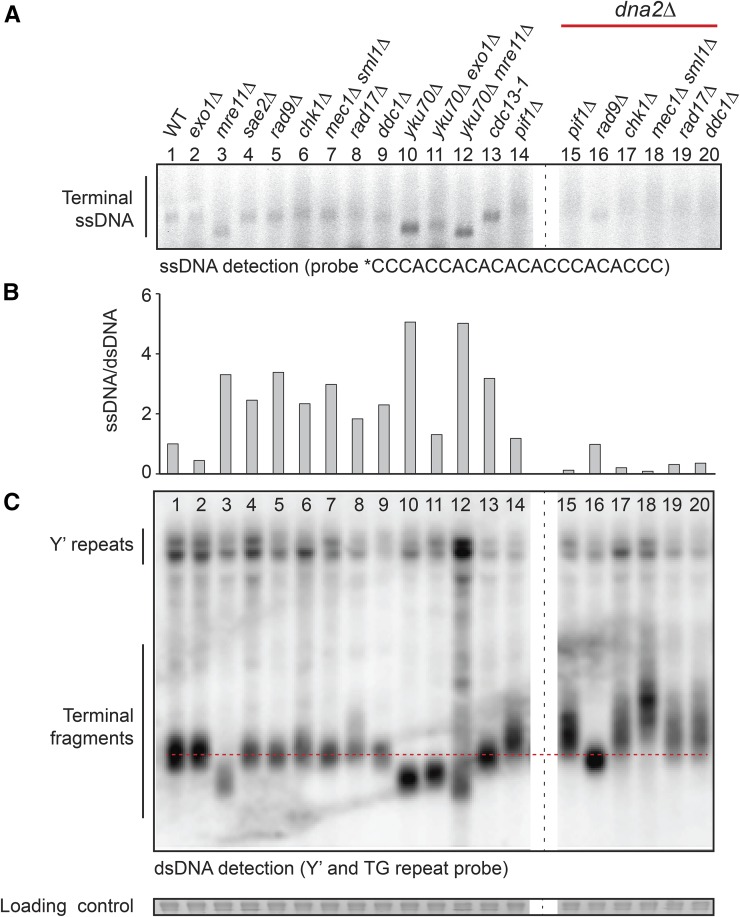

We next tested whether Dna2 affects the structure of telomeric DNA. We first tested for increased levels of 3′ ssDNA at telomeres in dna2∆ cells because this is seen in yku70∆ cells (Maringele and Lydall 2002). Furthermore, in fission yeast, Dna2 was shown to be involved in the generation of G-rich ssDNA at telomeres (Tomita et al. 2004). Importantly, it was reported that dna2∆ rad9∆ cells have abnormally low levels of telomeric 3′ G-rich ssDNA (Budd and Campbell 2013). Consistent with what was reported for rad9∆ dna2∆, chk1∆ dna2∆, mec1∆ dna2∆, rad17∆ dna2∆, ddc1∆ dna2∆, and pif1∆ dna2∆ cells all showed low levels of 3′ G-rich ssDNA at telomeres in comparison with DNA2 strains (Figure 3, A and B and Figures S3 and S4 in File S1). We conclude that all dna2∆ mutants have low levels of telomeric 3′ ssDNA. Interestingly, the dna2∆ ssDNA phenotype is opposite to that observed in other telomere-defective strains (cdc13-1 and yku70∆ mutants), which contain high levels of 3′ telomeric ssDNA (Maringele and Lydall 2002). We also checked for 5′ C-rich ssDNA and saw no evidence for increased levels of telomeric C-rich ssDNA (Figure S5 in File S1).

Figure 3.

Telomeres of dna2∆ strains are abnormal and have low levels of ssDNA. (A) An in-gel assay was performed to measure telomeric ssDNA. Saturated cultures were diluted at 1:25 (dna2∆ strains) or 1:50 (other strains) and grown for 6 hr until a concentration of ∼107 cells/ml was attained. DNA was isolated from dna2∆ strains at passage 6, except for dna2∆ pif1∆ strain which is of unknown passage number. Strains were as follows: wild type (WT) (DLY3001), exo1∆ (DLY1272), mre11∆ (DLY4457), sae2∆ (DLY1577), rad9∆ (DLY9593), chk1∆ (DLY10537), mec1∆ sml1∆ (DLY1326), rad17∆ (DLY7177), ddc1∆ (DLY8530), yku70∆ (DLY6885), yku70∆ exo1∆ (DLY1408), yku70∆ mre11∆ (DLY1845), cdc13-1 (DLY1108), pif1∆ (DLY4872), pif1∆ dna2∆ (DLY4690), rad9∆ dna2∆ (DLY10967), chk1∆ dna2∆ (DLY10975), mec1∆ sml1∆ dna2∆ (DLY11032), rad17∆ dna2∆ (DLY10981), and ddc1∆ dna2∆ (DLY10973). Strain details are in Table S1 in File S1. * indicates a 5′ IRDye 800 label. (B) ssDNA and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) were quantified using ImageJ analysis of the images shown in A and C. The ratio of ssDNA/dsDNA was plotted and the wild-type strain was given the value of “1”; all other ratios are expressed relative to the wild type. The telomeric regions quantified are indicated in Figure S3 in File S1. Analysis of independent strains of the same genotypes is shown in Figure S4 in File S1. (C) Southern blotting was performed to measure telomeric dsDNA with a Y’-TG probe. SYBR Safe was used as a loading control, as previously described (Holstein et al. 2014).

To search for other telomeric DNA phenotypes in dna2∆ strains, we examined telomere length by Southern blotting. Interestingly, the telomeres of chk1∆ dna2∆, mec1∆ dna2∆, rad17∆ dna2∆, and ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells were long, and in fact longer and more diffuse than pif1∆ strains, known to have very long telomeres (Schulz and Zakian 1994) (Figure 3C and Figures S4 and S6 in File S1). In contrast, and as reported before, rad9∆ dna2∆ telomeres were slightly shorter than the wild-type length (Budd and Campbell 2013). Rad9 is unique among checkpoint proteins because it binds chromatin and inhibits nuclease activity at telomeres and DSBs (Bonetti et al. 2015; Ngo and Lydall 2015). Perhaps, therefore, the comparatively short telomere length in rad9∆ dna2∆ mutants reflects this chromatin-binding function of Rad9 at telomeres. In summary, all dna2∆ mutants analyzed have abnormal telomere lengths and low levels of 3′ G-rich ssDNA.

Long telomeres are present in telomerase-deficient, recombination (RAD52)-dependent survivors (Wellinger and Zakian 2012). Recombination is also important to rescue stalled replication forks in telomeric sequences because the terminal location of telomeric DNA means that stalled forks cannot be rescued by forks arriving in the opposite direction, as in elsewhere in the genome. Because the telomeres in dna2∆ strains were often long, we wondered if recombination contributed to the viability of dna2∆ strains. Interestingly, Rad52 did seem to contribute to the viability of rad9∆ dna2∆ and ddc1∆ dna2∆ strains (Figure S7 in File S1). This strongly suggests that recombination-dependent mechanisms help dna2∆ cells maintain viability.

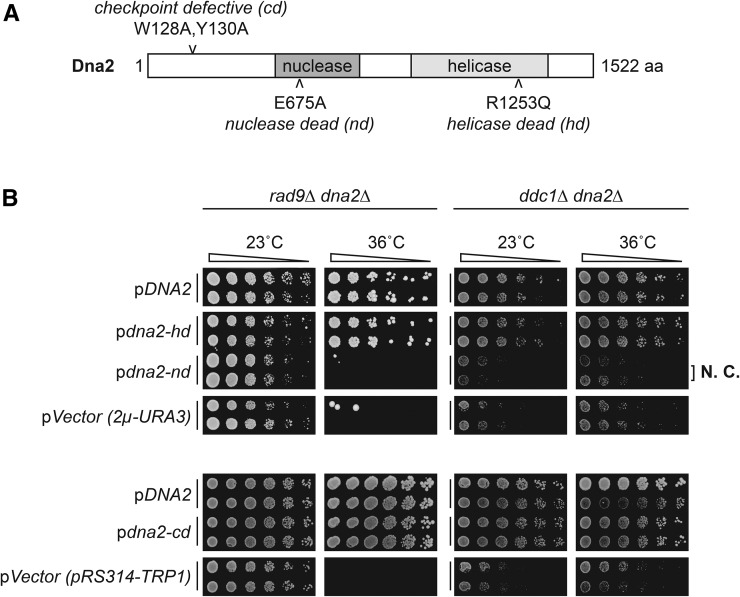

Dna2 nuclease is critical in checkpoint-defective cells

Dna2 is a nuclease as well as a helicase, and directly activates the central checkpoint kinase Mec1 (Kumar and Burgers 2013). Any of these functions might be important at telomeres or elsewhere. To test which biochemical activity is most important to cell fitness, we transformed nuclease-, helicase-, or checkpoint-defective alleles of DNA2 into rad9∆ dna2∆ or ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells, and measured growth at high temperature. It was clear that helicase dead and checkpoint-defective alleles rescued the dna2∆ defect and permitted growth at high temperatures (Figure 4B and Figure S8 in File S1). In contrast, the nuclease-defective allele of DNA2 did not rescue the dna2∆ growth defect. We conclude that the most critical function of Dna2 in checkpoint-defective yeast cells is its nuclease function.

Figure 4.

The nuclease domain of Dna2, but not helicase or checkpoint domains, confers viability of dna2∆ strains. (A) Domain structure of yeast Dna2. Mutations affecting checkpoint, nuclease, and helicase domains are indicated. (B) Spot test assay performed as in Figure 2B. Strains from passage 6 of original colony 3a (rad9∆ dna2∆, DLY10967), and 13d (ddc1∆ dna2∆, DLY10973) were used for plasmid transformation. rad9∆ dna2∆ and ddc1∆ dna2∆ strains carrying DNA2, empty vector or helicase-dead, nuclease-dead or checkpoint-dead alleles of DNA2 were inoculated into 2 ml –URA or –TRP media for plasmid selection and cultured for 48 hr, at 23°. Original images are in Figure S8 in File S1. Strain details are in Table S1 in File S1. Plasmid details are in Table S2 in File S1. N.C., no complementation.

dna2∆ mutants contain RPA-bound telomeres

dna2∆ cells are temperature sensitive, have telomere length phenotypes, and stimulate checkpoint pathways. However, paradoxically, dna2∆ cells have reduced levels of telomeric ssDNA when measured by in-gel assay. We reasoned that one plausible function for Dna2 nuclease activity was removal of ssDNA present in vivo that was not detectable in vitro. That is, unwound terminal telomeric DNA formed Y-shaped structures in vivo, with splayed arms of G-rich and C-rich ssDNA. The 5′ C-rich and 3′ G-rich ssDNA should bind RPA and CST (Cdc13, Stn1, and Ten1) (Nugent et al. 1996), respectively, with the RPA-coated 5′ ssDNA stimulating DNA damage checkpoint pathways. The ssDNA present on the arms of Y-shaped telomeres in vivo might not be detected by in-gel assays because complementary ssDNA strands would reanneal during DNA purification. Finally, telomere unwinding might be catalyzed by helicases (for example, Pif1) and high temperature, explaining the effects of pif1∆ and temperature on fitness of dna2∆ cells.

Most eukaryotic cells contain 3′ ssDNA overhangs on the G-rich strand of telomeric DNA, and this ssDNA is bound by proteins such as Pot1 and CST. If unwound telomeres occur in dna2∆ cells, then CST should still bind the 3′ strand, but in addition, RPA could bind the C-rich 5′ strand and stimulate the checkpoint. Presumably, in such a case, both RPA and CST complexes would colocalize at telomeres and stop the stimulation of the checkpoint pathway. To explore RPA and CST localization, the two largest subunits of each complex, Cdc13 and Rfa1, were tagged with yellow and cyan fluorescent proteins, respectively, and their localization in dna2∆ cells was examined by live-cell microscopy.

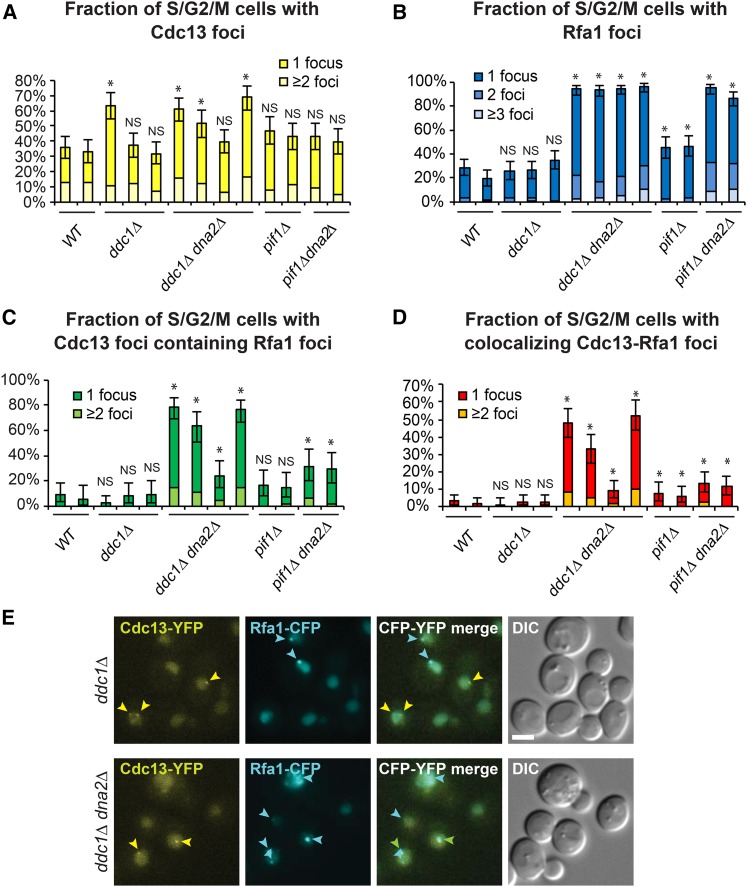

We examined Cdc13 and Rfa1 foci in ddc1∆ dna2∆, pif1∆ dna2∆ cells and wild-type, ddc1∆, pif1∆ controls. Because some of these cells grew poorly and may have altered cell-cycle distributions, we counted foci in budded cells (S/G2/M) as this is when RPA foci are more likely to be present (Figure 5). We observed broadly similar fractions of cells with Cdc13 foci in all cultures at the level of 30–70%, but checkpoint-defective strains ddc1∆ and ddc1∆ dna2∆ had somewhat higher levels (closer to 70%) (Figure 5A). In G1 cells the number of Cdc13 foci was smaller (<20%), but ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells tended to have consistently slightly higher levels (on average 15%) (Figure S9a in File S1). We conclude that DNA2 deletion has no strong effect on Cdc13 foci formation.

Figure 5.

dna2∆ mutants accumulate CST and RPA, the ssDNA binding complexes. (A–D) Percentages of Cdc13 foci, Rfa1 foci, or colocalized Cdc13-Rfa1 foci in dna2∆ and control strains are shown. (A) Percentage of budded (S/G2/M) cells with either Cdc13 foci only or Cdc13-Rfa1 foci. (B) Percentage of budded cells with either Rfa1 foci only or Cdc13-Rfa1 foci. (C) Percentage of budded cells with Cdc13 foci that colocalize with Rfa1 foci. (D) Percentage of budded cells with colocalizing Cdc13-Rfa1 foci. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (n = 213–437, from two independent cultures of each strain). * indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05) determined using Fisher’s exact test. Strains are as follows: wild type (WT) (DLY12342, DLY12343), ddc1∆ (DLY12282, DLY12280, DLY12283), ddc1∆ dna2∆ (DLY12281, DLY12341, DLY12284, DLY12279), pif1∆ (DLY12346, DLY12347), and pif1∆ dna2∆ (DLY12344, DLY12345). (E) An example of live-cell images is shown. Cdc13-Rfa1 colocalized foci are indicated by green arrows, Cdc13 foci by yellow arrows, and Rfa1 foci by blue arrows. Bar, 3 µm. Strain details are in Table S1 in File S1.

We also searched for Rfa1 foci and observed that, on average, 30% of budded and 10% of unbudded control cells contained Rfa1 foci (Figure 5B and Figure S9b in File S1). In contrast, ddc1∆ dna2∆ and pif1∆ dna2∆ cultures contained a much higher fraction of budded cells with Rfa1 foci. Generally, >80% of ddc1∆ dna2∆ and pif1∆ dna2∆ cells, and ∼40% of pif1∆ cells contained at least one Rfa1 focus (Figure 5B), suggesting that high levels of DNA damage and ssDNA are present in these strains. In G1 cells, the number of Rfa1 foci was smaller (up to 80%), and cells hardly ever contained more than one Rfa1 focus (Figure S9b in File S1).

If the Rfa1 foci observed in dna2∆ cells were primarily at telomeres, rather than at DSBs or long flaps on Okazaki fragments elsewhere in the genome, then Rfa1 foci in dna2∆ cells should preferentially localize at telomeres. Assuming Cdc13 foci are at telomeres (Khadaroo et al. 2009), then >60% of these telomeric loci in ddc1∆ dna2∆ budded cells colocalized with Rfa1 (Figure 5C). In contrast, <10% of Cdc13 foci contained Rfa1 in wild-type or ddc1∆ budded cells, suggesting low Rfa1 at telomeres in wild-type and ddc1∆ strains. This suggests that RPA-bound ssDNA occurs at high frequency near telomeres in ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells. pif1∆ dna2∆ cells contained nearly as many Rfa1 foci and Cdc13 foci as ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells, but less Cdc13 foci contained Rfa1 (∼30%). We conclude that pif1∆ dna2∆ cells have less RPA-bound ssDNA at telomeres than ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells. Interestingly, pif1∆ single mutants also contained more Rfa1 foci than wild-type cells, and more colocalization of Rfa1 and Cdc13 (∼5%) (Figure 5, B–D). This suggests that pif1∆ cells, which contain long telomeres, show comparatively high levels of RPA binding at telomeres, possibly due to the difficulty of replicating through long stretches of telomeric DNA.

Overall, of all the genotypes examined, ddc1∆ dna2∆ mutants had the highest fraction of Cdc13 foci that contain Rfa1, Rfa1 foci that contain Cdc13, and Cdc13-Rfa1 foci (Figure 5, C and D and Figure S9f in File S1). These data are consistent with a model in which both G-rich and C-rich ssDNA are found at high levels at telomeres in ddc1∆ dna2∆ cells. Interestingly, pif1∆ dna2∆ cells also contained increased levels of CST/RPA-bound ssDNA, suggesting that Pif-independent helicases may unwind telomeric C-rich and G-rich ssDNA in the absence of Pif1, to generate substrates for RPA binding.

dna2∆ lethality is suppressed by mph1∆ and pol32∆, but not sgs1∆

To search for additional activities that might unwind telomeric DNA, like Pif1, we examined genes affecting likely candidates. Sgs1 was a candidate since it functions with Dna2 in resection of DSBs and uncapped telomeres (Cejka et al. 2010; Ngo et al. 2014), but its deletion did not suppress dna2∆ (Figure S10a in File S1), as has been reported by others (Hoopes et al. 2002; Weitao et al. 2003; Budd et al. 2005). On this basis Sgs1 does not seem to contribute to telomere unwinding, or if it does, it also has other functions that are essential in dna2∆ strains.

We examined Mph1, because like Pif1, Mph1 stimulates Dna2 activity on 5′ flaps in vitro (Kang et al. 2009). Interestingly, mph1∆ suppressed dna2∆. The effect of mph1∆ was similar to checkpoint mutations, but not as strong as pif1∆ (Figure S10, a–c in File S1). Therefore loss of Mph1, a 3′ to 5′ helicase, like loss of Pif1, a 5′ to 3′ helicase, suppresses the inviability of dna2∆ cells. Given the polarity of the Mph1 helicase, it would most likely engage with the 3′ G-rich overhanging strand to unwind telomeric DNA, and compete with CST for this substrate. To test this hypothesis, mph1∆ was combined with cdc13-1 and the temperature-sensitive phenotype was scored. Interestingly, mph1∆ mildly suppresses the temperature-dependent growth defects of cdc13-1 mutants (Figure S10d in File S1). This suggests that Mph1 and CST compete to bind the same G-rich strand at telomeres, and is consistent with the idea that Mph1 engages with the 3′ telomeric overhang to unwind telomeric double-stranded DNA.

Finally, we tested Pol32, a DNA Pol δ subunit, which helps displace 5′ ends of Okazaki fragments. It had been reported that pol32∆ suppresses some alleles of DNA2, and weakly suppresses dna2∆ (Budd et al. 2006; Stith et al. 2008). Interestingly, we confirmed that pol32∆ suppressed dna2∆. In contrast to checkpoint mutations, pol32∆ suppressed dna2∆ at high temperature (30° and 23°) but not at 20° (Figure S10, a–c in File S1). This temperature-dependent suppression may be explained by the fact that pol32∆ mutants are cold sensitive (Gerik et al. 1998).

Discussion

We report that loss of proteins affecting numerous aspects of the DNA damage response permit budding yeast cells to divide indefinitely in the absence of the essential protein Dna2. Loss of DNA damage checkpoint proteins (Rad9, Ddc1, Rad17, Chk1, and Mec1) or Pif1, a 5′ to 3′ helicase, Mph1, a 3′ to 5′ helicase, or Pol32, a DNA polymerase δ subunit, suppress the inviability of dna2∆ cells. The suppression of dna2∆ by checkpoint mutations makes dna2∆ mutants more similar to telomere-defective strains than general DNA replication-defective strains (Dubarry et al. 2015). Consistent with this, dna2∆ strains show telomere length phenotypes and a high degree of colocalization of Cdc13, a telomeric G-rich ssDNA binding protein, and Rfa1, a more general ssDNA binding protein in vivo. dna2∆ mutants are also temperature sensitive and have low levels of telomeric G-rich ssDNA. The nuclease function of Dna2, but not helicase and checkpoint functions, is critical to confer the viability of dna2∆ checkpoint∆ strains at high temperature.

The low levels of telomeric 3′ ssDNA that we detect at telomeres of dna2∆ mutants by in vitro in-gel assay is the opposite phenotype to the high levels of 3′ ssDNA found at telomeres in other telomere-defective strains suppressed by checkpoint gene mutations (for example, cdc13-1 and yku70∆ mutants) (Maringele and Lydall 2002; Ngo et al. 2014). Our explanation is that high levels of RPA-coated C-rich ssDNA and comparatively normal levels of CST-coated G-rich ssDNA are present at unwound telomeres of dna2∆ cells in vivo. This is detected as colocalization by live-cell imaging, but when DNA is extracted, it renatures during purification and ssDNA is not detected.

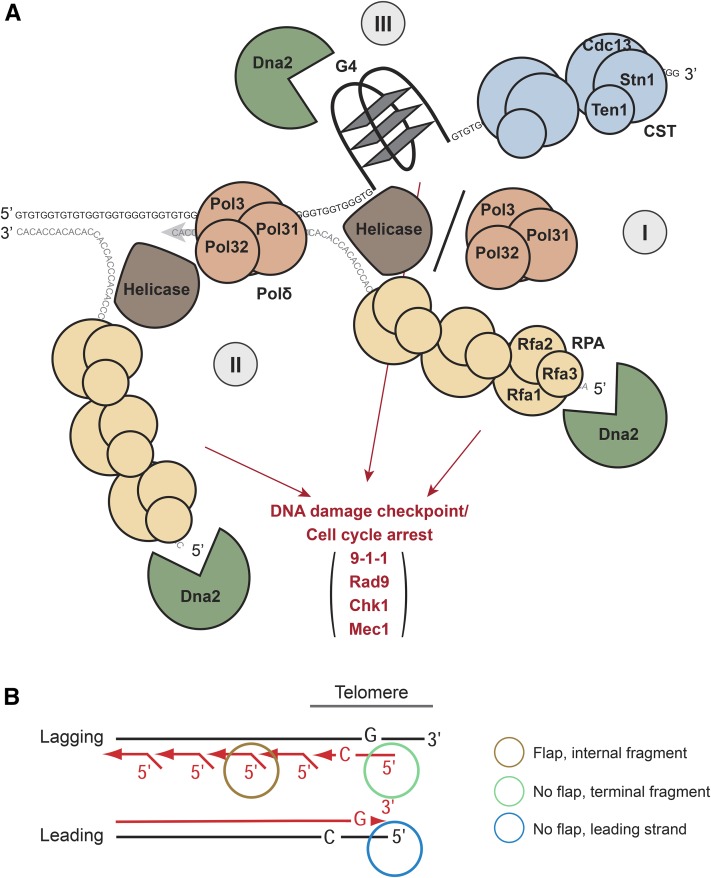

There are at least three plausible scenarios for why Dna2 might have its most critical functions at or near telomeres (Figure 6A). One model that best fits all our data is that Dna2 nuclease activity removes potentially harmful, RPA-coated 5′ C-rich ssDNA at the termini of telomeres (Figure 6A, scenario I). In this model, helicases like Pif1 or Mph1 unwind the telomeric termini. The G-rich strand is bound by the telomeric CST complex and is presumably quite benign, but the C-rich strand is bound by RPA and potentially stimulates DNA damage checkpoint activity. Pol32, a subunit of DNA polymerase δ with strand displacement activity (Podust et al. 1995; Maga et al. 2001), might also generate ssDNA at the telomeric terminus, if CST recruits Pol α for lagging strand fill-in, which in turn recruits Pol δ (Waga and Stillman 1998; Maga et al. 2000; Burgers 2009).

Figure 6.

Three plausible roles for Dna2 in removing unwound RPA-coated ssDNA at telomeres. (A) Three scenarios for Dna2 activity. Scenario I: 5′ RPA-coated ssDNA cleavage at telomeric termini. Telomere ends are unwound by helicases, for example, Pif1 or Mph1. The 3′ G-rich strand is bound by CST and the 5′ C-rich strand is bound by RPA, a substrate for Dna2 cleavage. Scenario II: Processing of long flaps on Okazaki fragments near telomeres. DNA polymerase δ displacement activity, stimulated by helicase(s), generates long flaps on an Okazaki fragment near telomere. Long C-rich flap, bound by RPA, are subjected to Dna2 cleavage. Scenario III: G-quadruplex unwinding and processing. G-quadruplexes formed on telomeric G-rich ssDNA are unwound or processed by Dna2. All proteins were drawn to scale. (B) Lagging and leading strand replication at telomeres. Short red arrows indicate Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand. The long red arrow indicates replicated leading strand. The brown circle indicates the flap formed on an internal Okazaki fragment. The green circle indicates no flap on the terminal telomeric Okazaki fragment. The blue circle indicates no flap on the leading strand template.

Another potential role for Dna2 at telomeres is in removing long flaps of subtelomeric Okazaki fragments (Figure 6A, scenario II). Finally, Dna2 nuclease activity may be needed at stalled replication forks in telomeric regions (Figure 6A, scenario III). For example, mammalian and yeast telomeres are G-rich, difficult to replicate, and can form G-quadruplexes that might be processed by Dna2 (Gilson and Geli 2007; Masuda-Sasa et al. 2008; Lin et al. 2013; Maestroni et al. 2017). At other genomic locations, other substrates for Dna2 (e.g., DSBs or stalled replication forks) can also occur (Hu et al. 2012; Ngo et al. 2014), but our evidence is that telomeres are particularly reliant on Dna2.

If Dna2 acts at the very termini of telomeres (Figure 6A, scenario I), either the lagging strand, the leading strand, or both might be targets for Dna2 (Figure 6B). It is well-established that the leading and lagging strands of telomeres are processed by different mechanisms (Parenteau and Wellinger 1999; Wu et al. 2012; Bonetti et al. 2013; Soudet et al. 2014). After lagging strand replication is complete, the very terminus cannot be fully replicated because of the end replication problem. Irrespective of whether the most terminal Okazaki fragment is created by passage of the replication fork or CST recruitment of Pol α, it is unusual as unlike >99% of the other Okazaki fragments, it will not contain a flap at its 5′ end (Figure 6B). Perhaps the absence of a flap and/or a polymerase facilitates helicase engagement. The leading strand telomere end, which is thought to be blunt after the replication fork has passed, may also be susceptible to helicase activities.

We and others (Budd and Campbell 2013) have shown that dna2∆ rad9∆ cells have a short telomere phenotype. All other dna2∆ strains, including other checkpoint-defective strains, have long telomeres. Hence it is not telomere length per se that determines the survival of dna2∆ cells. Rad9, like its human ortholog 53BP1, binds chromatin and inhibits resection at telomere-defective cdc13-1 cells and at DSBs (Iwabuchi et al. 2003; Lazzaro et al. 2008; Bunting et al. 2010; Ngo and Lydall 2015). Perhaps Rad9 binding to chromatin also inhibits helicase activity, telomere unwinding, and nuclease activity. Presumably unwound telomeres are also more susceptible to nucleases (other than Dna2). Consistent with this, the 9-1-1 complex recruits Dna2 and Exo1 nuclease to uncapped telomeres (Ngo and Lydall 2015), and ddc1∆ dna2∆ and rad17∆ dna2∆ mutants, defective in 9-1-1, have long telomeres.

Telomeres in all organisms are difficult to replicate and need to be protected from the harmful aspects of the DNA damage response. Telomeric structures like t-loops, and proteins like CST, shelterin, and the Ku heterodimer may help protect telomeric DNA from being unwound by helicases. Our experiments in yeast suggest that Dna2 is critical for removing RPA-coated C-rich ssDNA at unwound telomeres. DNA2 is an essential gene in budding and fission yeasts, C. elegans, mice, and human cells. Interestingly, C. elegans dna2∆ mutants show temperature-dependent delayed lethality (Lee et al. 2003), suggesting that temperature-dependent telomere unwinding in C. elegans creates substrates for Dna2 nuclease activity at high temperatures.

Dna2 localizes at telomeres in yeast, humans, and mice, and Dna2 affects telomere phenotypes in all these organisms (Choe et al. 2002; Lin et al. 2013). Dna2, checkpoint proteins, Pif1 and Mph1 helicases, and Pol32 are all conserved between human and yeast cells, and affect telomere-related human diseases such as cancer, suggesting our observations may be relevant to human disease (Paeschke et al. 2013; Byrd and Raney 2015; Ceccaldi et al. 2016). It will be interesting to see if telomere-specific functions for Dna2 are conserved across eukaryotes.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.118.300809/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to Lata Balakrishnan, Peter Burgers, Judy Campbell, Laura Maringele, and Duncan Smith for advice and input. This work was funded by European Union Marie Curie International Training Network (ITN) network CodeAge (FP7-PEOPLE-2011-ITN) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (BB/M002314/1). The Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation (DFF) and the Villum Foundation supported the work performed by M.L.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: D. Bishop

Literature Cited

- Addinall S. G., Downey M., Yu M., Zubko M. K., Dewar J., et al. , 2008. A genomewide suppressor and enhancer analysis of cdc13–1 reveals varied cellular processes influencing telomere capping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 180: 2251–2266. 10.1534/genetics.108.092577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S. H., Bae K. H., Kim J. A., Seo Y. S., 2001. RPA governs endonuclease switching during processing of Okazaki fragments in eukaryotes. Nature 412: 456–461. 10.1038/35086609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan L., Bambara R. A., 2013. Okazaki fragment metabolism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5: a010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti D., Martina M., Falcettoni M., Longhese M. P., 2013. Telomere-end processing: mechanisms and regulation. Chromosoma 123: 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti D., Villa M., Gobbini E., Cassani C., Tedeschi G., et al. , 2015. Escape of Sgs1 from Rad9 inhibition reduces the requirement for Sae2 and functional MRX in DNA end resection. EMBO Rep. 16: 351–361. 10.15252/embr.201439764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Campbell J. L., 1997. A yeast replicative helicase, Dna2 helicase, interacts with yeast FEN-1 nuclease in carrying out its essential function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 2136–2142. 10.1128/MCB.17.4.2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Campbell J. L., 2013. Dna2 is involved in CA strand resection and nascent lagging strand completion at native yeast telomeres. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 29414–29429. 10.1074/jbc.M113.472456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Choe W. C., Campbell J. L., 1995. DNA2 encodes a DNA helicase essential for replication of eukaryotic chromosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 26766–26769. 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Tong A. H. Y., Polaczek P., Peng X., Boone C., et al. , 2005. A network of multi-tasking proteins at the DNA replication fork preserves genome stability. PLoS Genet. 1: e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Reis C. C., Smith S., Myung K., Campbell J. L., 2006. Evidence suggesting that Pif1 helicase functions in DNA replication with the Dna2 helicase/nuclease and DNA polymerase delta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 2490–2500. 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2490-2500.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Antoshechkin I. A., Reis C., Wold B. J., Campbell J. L., 2011. Inviability of a DNA2 deletion mutant is due to the DNA damage checkpoint. Cell Cycle 10: 1690–1698. 10.4161/cc.10.10.15643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting S. F., Callen E., Wong N., Chen H. T., Polato F., et al. , 2010. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell 141: 243–254. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers P. M., 2009. Polymerase dynamics at the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 4041–4045. 10.1074/jbc.R800062200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd A. K., Raney K. D., 2015. A parallel quadruplex DNA is bound tightly but unfolded slowly by pif1 helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 6482–6494. 10.1074/jbc.M114.630749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccaldi R., Sarangi P., D’Andrea A. D., 2016. The Fanconi anaemia pathway: new players and new functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17: 337–349. 10.1038/nrm.2016.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cejka P., Cannavo E., Polaczek P., Masuda-Sasa T., Pokharel S., et al. , 2010. DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature 467: 112–116. 10.1038/nature09355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai W., Zheng L., Shen B., 2013. DNA2, a new player in telomere maintenance and tumor suppression. Cell Cycle 12: 1985–1986. 10.4161/cc.25306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe W., Budd M., Imamura O., Hoopes L., Campbell J. L., 2002. Dynamic localization of an Okazaki fragment processing protein suggests a novel role in telomere replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 4202–4217. 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4202-4217.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar J. M., Lydall D., 2010. Pif1- and Exo1-dependent nucleases coordinate checkpoint activation following telomere uncapping. EMBO J. 29: 4020–4034. 10.1038/emboj.2010.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar J. M., Lydall D., 2012. Simple, non-radioactive measurement of single-stranded DNA at telomeric, sub-telomeric, and genomic loci in budding yeast. Methods Mol. Biol. 920: 341–348. 10.1007/978-1-61779-998-3_24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Valentin M., Therkildsen C., Veerla S., Jonsson M., Bernstein I., et al. , 2013. Distinct gene expression signatures in lynch syndrome and familial colorectal cancer type x. PLoS One 8: e71755 10.1371/journal.pone.0071755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubarry M., Lawless C., Banks A. P., Cockell S., Lydall D., 2015. Genetic networks required to coordinate chromosome replication by DNA polymerases alpha, delta, and epsilon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G3 5: 2187–2197. 10.1534/g3.115.021493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxin J. P., Dao B., Martinsson P., Rajala N., Guittat L., et al. , 2009. Human Dna2 is a nuclear and mitochondrial DNA maintenance protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29: 4274–4282. 10.1128/MCB.01834-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerik K. J., Li X., Pautz A., Burgers P. M., 1998. Characterization of the two small subunits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 19747–19755. 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson E., Geli V., 2007. How telomeres are replicated. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 825–838. 10.1038/nrm2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R., Tsien R. Y., 1996. Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr. Biol. 6: 178–182. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00450-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein E. M., Clark K. R., Lydall D., 2014. Interplay between nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and DNA damage response pathways reveals that Stn1 and Ten1 are the key CST telomere-cap components. Cell Rep. 7: 1259–1269. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein E. M., Ngo G., Lawless C., Banks P., Greetham M., et al. , 2017. Systematic analysis of the DNA damage response network in telomere defective budding yeast. G3 7: 2375–2389. 10.1534/g3.117.042283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes L. L. M., Budd M., Choe W., Weitao T., Campbell J. L., 2002. Mutations in DNA replication genes reduce yeast life span. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 4136–4146. 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4136-4146.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Sun L., Shen F., Chen Y., Hua Y., et al. , 2012. The intra-S phase checkpoint targets Dna2 to prevent stalled replication forks from reversing. Cell 149: 1221–1232. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi K., Basu B. P., Kysela B., Kurihara T., Shibata M., et al. , 2003. Potential role for 53BP1 in DNA end-joining repair through direct interaction with DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 36487–36495. 10.1074/jbc.M304066200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia P. P., Junaid M., Ma Y. B., Ahmad F., Jia Y. F., et al. , 2017. Role of human DNA2 (hDNA2) as a potential target for cancer and other diseases: a systematic review. DNA Repair (Amst.) 59: 9–19. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. Y., Choi E., Bae S. H., Lee K. H., Gim B. S., et al. , 2000. Genetic analyses of Schizosaccharomyces pombe dna2(+) reveal that dna2 plays an essential role in Okazaki fragment metabolism. Genetics 155: 1055–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y. H., Kang M. J., Kim J. H., Lee C. H., Cho I. T., et al. , 2009. The MPH1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae functions in Okazaki fragment processing. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 10376–10386. 10.1074/jbc.M808894200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao H. I., Bambara R. A., 2003. The protein components and mechanism of eukaryotic Okazaki fragment maturation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38: 433–452. 10.1080/10409230390259382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadaroo B., Teixeira M. T., Luciano P., Eckert-Boulet N., Germann S. M., et al. , 2009. The DNA damage response at eroded telomeres and tethering to the nuclear pore complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 11: 980–987. 10.1038/ncb1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Burgers P. M., 2013. Lagging strand maturation factor Dna2 is a component of the replication checkpoint initiation machinery. Genes Dev. 27: 313–321. 10.1101/gad.204750.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Peng X., Daley J., Yang L., Shen J., et al. , 2017. Inhibition of DNA2 nuclease as a therapeutic strategy targeting replication stress in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 6: e319 10.1038/oncsis.2017.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro F., Sapountzi V., Granata M., Pellicioli A., Vaze M., et al. , 2008. Histone methyltransferase Dot1 and Rad9 inhibit single-stranded DNA accumulation at DSBs and uncapped telomeres. EMBO J. 27: 1502–1512. 10.1038/emboj.2008.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. H., Lee M. H., Lee T. H., Han J. W., Park Y. J., et al. , 2003. Dna2 requirement for normal reproduction of Caenorhabditis elegans is temperature-dependent. Mol. Cells 15: 81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. E., Moore J. K., Holmes A., Umezu K., Kolodner R. D., et al. , 1998. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell 94: 399–409. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81482-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levikova M., Cejka P., 2015. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dna2 can function as a sole nuclease in the processing of Okazaki fragments in DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 7888–7897. 10.1093/nar/gkv710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levikova M., Klaue D., Seidel R., Cejka P., 2013. Nuclease activity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dna2 inhibits its potent DNA helicase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: E1992–E2001. 10.1073/pnas.1300390110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W., Sampathi S., Dai H., Liu C., Zhou M., et al. , 2013. Mammalian DNA2 helicase/nuclease cleaves G-quadruplex DNA and is required for telomere integrity. EMBO J. 32: 1425–1439. 10.1038/emboj.2013.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall D., Weinert T., 1995. Yeast checkpoint genes in DNA damage processing: implications for repair and arrest. Science 270: 1488–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestroni L., Matmati S., Coulon S., 2017. Solving the telomere replication problem. Genes (Basel) 8: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga G., Stucki M., Spadari S., Hubscher U., 2000. DNA polymerase switching: I. Replication factor C displaces DNA polymerase alpha prior to PCNA loading. J. Mol. Biol. 295: 791–801. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga G., Villani G., Tillement V., Stucki M., Locatelli G. A., et al. , 2001. Okazaki fragment processing: modulation of the strand displacement activity of DNA polymerase delta by the concerted action of replication protein A, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and flap endonuclease-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 14298–14303. 10.1073/pnas.251193198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maringele L., Lydall D., 2002. EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70Delta mutants. Genes Dev. 16: 1919–1933. 10.1101/gad.225102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda-Sasa T., Polaczek P., Peng X. P., Chen L., Campbell J. L., 2008. Processing of G4 DNA by Dna2 helicase/nuclease and replication protein A (RPA) provides insights into the mechanism of Dna2/RPA substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 24359–24373. 10.1074/jbc.M802244200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimitou E. P., Symington L. S., 2008. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455: 770–774. 10.1038/nature07312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myler L. R., Gallardo I. F., Zhou Y., Gong F., Yang S. H., et al. , 2016. Single-molecule imaging reveals the mechanism of Exo1 regulation by single-stranded DNA binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: E1170–E1179. 10.1073/pnas.1516674113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navadgi-Patil V. M., Burgers P. M., 2009a A tale of two tails: activation of DNA damage checkpoint kinase Mec1/ATR by the 9–1-1 clamp and by Dpb11/TopBP1. DNA Repair (Amst.) 8: 996–1003. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navadgi-Patil V. M., Burgers P. M., 2009b The unstructured C-terminal tail of the 9–1-1 clamp subunit Ddc1 activates Mec1/ATR via two distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell 36: 743–753. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo G. H., Lydall D., 2015. The 9–1-1 checkpoint clamp coordinates resection at DNA double strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 5017–5032. 10.1093/nar/gkv409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo G. H., Balakrishnan L., Dubarry M., Campbell J. L., Lydall D., 2014. The 9–1-1 checkpoint clamp stimulates DNA resection by Dna2-Sgs1 and Exo1. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 10516–10528. 10.1093/nar/gku746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent C. I., Hughes T. R., Lue N. F., Lundblad V., 1996. Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science 274: 249–252. 10.1126/science.274.5285.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormö M., Cubitt A. B., Kallio K., Gross L. A., Tsien R. Y., et al. , 1996. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science 273: 1392–1395. 10.1126/science.273.5280.1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeschke K., Bochman M. L., Garcia P. D., Cejka P., Friedman K. L., et al. , 2013. Pif1 family helicases suppress genome instability at G-quadruplex motifs. Nature 497: 458–462. 10.1038/nature12149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenteau J., Wellinger R. J., 1999. Accumulation of single-stranded DNA and destabilization of telomeric repeats in yeast mutant strains carrying a deletion of RAD27. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 4143–4152. 10.1128/MCB.19.6.4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G., Dai H., Zhang W., Hsieh H. J., Pan M. R., et al. , 2012. Human nuclease/helicase DNA2 alleviates replication stress by promoting DNA end resection. Cancer Res. 72: 2802–2813. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. A., Chan A., Paeschke K., Zakian V. A., 2015. The pif1 helicase, a negative regulator of telomerase, acts preferentially at long telomeres. PLoS Genet. 11: e1005186 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike J. E., Burgers P. M., Campbell J. L., Bambara R. A., 2009. Pif1 helicase lengthens some Okazaki fragment flaps necessitating Dna2 nuclease/helicase action in the two-nuclease processing pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 25170–25180. 10.1074/jbc.M109.023325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podust V. N., Podust L. M., Muller F., Hubscher U., 1995. DNA polymerase delta holoenzyme: action on single-stranded DNA and on double-stranded DNA in the presence of replicative DNA helicases. Biochemistry 34: 5003–5010. 10.1021/bi00015a011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puddu F., Granata M., Di Nola L., Balestrini A., Piergiovanni G., et al. , 2008. Phosphorylation of the budding yeast 9–1-1 complex is required for Dpb11 function in the full activation of the UV-induced DNA damage checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 4782–4793. 10.1128/MCB.00330-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M. L., Bambara R. A., 2006. Reconstituted Okazaki fragment processing indicates two pathways of primer removal. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 26051–26061. 10.1074/jbc.M604805200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz V. P., Zakian V. A., 1994. The saccharomyces PIF1 DNA helicase inhibits telomere elongation and de novo telomere formation. Cell 76: 145–155. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90179-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F., Fink G. R., Hicks J. B., 1986. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Shim E. Y., Chung W. H., Nicolette M. L., Zhang Y., Davis M., et al. , 2010. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 29: 3370–3380. 10.1038/emboj.2010.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S., Gallina I., Eckert-Boulet N., Lisby M., 2012. Live cell microscopy of DNA damage response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 920: 433–443. 10.1007/978-1-61779-998-3_30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soudet J., Jolivet P., Teixeira M. T., 2014. Elucidation of the DNA end-replication problem in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 53: 954–964. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. A., Miller A. S., Campbell J. L., Bambara R. A., 2008. Dynamic removal of replication protein A by Dna2 facilitates primer cleavage during Okazaki fragment processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 31356–31365. 10.1074/jbc.M805965200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith C. M., Sterling J., Resnick M. A., Gordenin D. A., Burgers P. M., 2008. Flexibility of eukaryotic Okazaki fragment maturation through regulated strand displacement synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 34129–34140. 10.1074/jbc.M806668200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss C., Kornowski M., Benvenisty A., Shahar A., Masury H., et al. , 2014. The DNA2 nuclease/helicase is an estrogen-dependent gene mutated in breast and ovarian cancers. Oncotarget 5: 9396–9409. 10.18632/oncotarget.2414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T., Zaitseva E. M., Kowalczykowski S. C., 1997. A single-stranded DNA-binding protein is needed for efficient presynaptic complex formation by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad51 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 7940–7945. 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K., Kibe T., Kang H. Y., Seo Y. S., Uritani M., et al. , 2004. Fission yeast Dna2 is required for generation of the telomeric single-strand overhang. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 9557–9567. 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9557-9567.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waga S., Stillman B., 1998. The DNA replication fork in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67: 721–751. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T. A., Kiser G. L., Hartwell L. H., 1994. Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 8: 652–665. 10.1101/gad.8.6.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitao T., Budd M., Campbell J. L., 2003. Evidence that yeast SGS1, DNA2, SRS2, and FOB1 interact to maintain rDNA stability. Mutat. Res. 532: 157–172. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Sanger Institute. COSMIC, the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer Database. Available at: http://cancer.13 sanger.ac.uk/cosmic. Accessed: September 19, 2017.

- Wellinger R. J., Zakian V. A., 2012. Everything you ever wanted to know about Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres: beginning to end. Genetics 191: 1073–1105. 10.1534/genetics.111.137851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Takai H., De Lange T., 2012. Telomeric 3′ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell 150: 39–52. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Chung W. H., Shim E. Y., Lee S. E., Ira G., 2008. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 134: 981–994. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Elledge S. J., 2003. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300: 1542–1548. 10.1126/science.1083430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. Table S1 in File S1 lists all strains.