Introduction

HIV-infected persons with sustained viremic control in the United States and similar high-income areas are now projected to live a close-to-normal lifespan[1, 2]. This welcome shift in epidemiology has introduced new challenges into the clinical care of individuals living with HIV, as longevity has been accompanied by a higher burden of chronic diseases and comorbidities, or ‘multimorbidity’[3]. Many of these comorbid diseases are not direct results of HIV infection or immunosuppression (and are thus termed HIV-associated non-AIDS, or ‘HANA,’ conditions); nonetheless, they are independently associated with HIV infection and may present earlier, more frequently, or more severely in persons with HIV infection than in those without.

Chronic pulmonary disease and respiratory symptoms occur at high frequency among HIV-infected individuals, and clinically relevant pulmonary conditions are commonly non-infectious. Non-infectious pulmonary conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gas exchange abnormalities (i.e. diffusing capacity impairment), asthma, and cardiopulmonary dysfunction are prevalent among persons with HIV, and HIV infection is associated with many of these disorders and is an independent risk factor for COPD[4, 5]. Like other HANA conditions, features unique to HIV may contribute to chronic pulmonary disease in HIV. Such mediators include chronic inflammation and aberrant immune activation and regulation, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and pulmonary and systemic dysbiosis, among others. Further complicating the assessment, HIV infected populations are enriched for confounders of the relationship between infection and lung health, including chronic and recurrent infection, injection and inhalational drug use, and – most importantly – alarmingly high rates of tobacco smoking. Unraveling the contributions of each of these contributors is a focus of current research in HIV-associated comorbidities.

Of additional concern, conditions such as COPD, diffusing capacity impairment, and cardiopulmonary dysfunction are not only becoming more frequent as the HIV-infected population ages, but they are also progressive. The incident health burden in this population will therefore likely worsen over the coming decades. Furthermore, progression may be more pronounced or more rapid in persons with HIV, particularly since the contributors to disease development and progression are incompletely understood, and no therapies have been tested specifically in HIV-infected individuals.

In this article, focused primarily on antiretroviral therapy (ART) era data, we will briefly review infectious lung disease in association with HIV, describe respiratory symptoms encountered in persons with HIV, and review the literature related to the most common non-infectious chronic lung diseases in HIV. We will discuss risk factors and pathogenesis of disease, outline available data describing differences in disease characteristics between HIV-infected and HIV–uninfected groups, and describe gaps in the literature and opportunities for further investigation to help better prevent and manage chronic lung disease in this unique population.

Infectious Pulmonary Complications in the Current Era

While infectious complications of HIV, including pneumonia, are generally less common than they were in the pre-ART era[6, 7], pulmonary infection still contributes significantly to health burden among individuals with HIV[8]. In fact, pulmonary infection remains the leading reason for hospitalization[9]. Continued pneumonia risk may be in part due to incomplete penetrance of ART coverage even in high-access regions. Up to 14% of HIV-infected persons in the United States are not aware of their infection, and a surprisingly low percentage (30%) achieve viral suppression[10]. Even in well-treated individuals, pulmonary immunity is not completely normal, potentially predisposing to an increased risk of pneumonia despite CD4 cell count reconstitution[11]. Thus, pulmonary infection continues to threaten at-risk individuals.

Bacterial pneumonia with typical infectious organisms (S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus, Pseudomonas, Staph species, and Klebsiella) is the most frequent cause of lower respiratory tract infection in patients with HIV[8, 12]. Risk factors, as expected, include low CD4 cell count, absence of ART, and tobacco smoking, as well as injection drug use and chronic infectious hepatitis[8]. Seasonal influenza has not been proven to be more frequent among persons with HIV, but disease may be more severe, particularly in those with CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/uL and those not taking ART[13–15]. Importantly, influenza vaccination rates among persons with HIV remain suboptimal, at 26–57% in recent cohort studies[16, 17].

Less-typical infections, which are in large part dependent on deficiencies in cell-mediated immunity, continue to occur in patients with HIV, particularly in those with a new diagnosis of AIDS or those who lack optimal viral control. Tuberculosis is declining among persons with HIV on ART therapy[18, 19], as ART is associated with decrease in incidence of TB across populations and at all levels of CD4 cell count[20]. Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) remains a leading cause of opportunistic infection, though the incidence has significantly decreased following the advent of ART[6]. Risk factors include CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/uL, lack of PCP prophylaxis, homelessness, and history of other AIDS-defining illness[21, 22]. Crypotoccus and the endemic mycoses (Histoplasma, Coccidiodes, and Blastomyces) may all cause pneumonia in persons with HIV. Cryptococcosis was a frequent fungal pathogen in the pre-ART era, but incidence has decreased dramatically in the ART era[21, 23]. Although primary pulmonary disease occurs, it is now rare[23]. Regarding the endemic mycoses, lower CD4 cell count is associated with coccidioidomycosis, and pulmonary disease severity is worse with lower CD4 cell counts, higher HIV viral load, and absence of ART[24]. Histoplasma infection is associated with detectable viremia, suggesting significant risk in association with poor viral control and immune function[25, 26]. There are no data available regarding epidemiology of Blastomyces, but blastomycosis should be considered as a potential fungal pathogens in persons who have visited endemic regions.

Respiratory Symptoms and Functional Capacity

Respiratory symptoms are common among HIV-infected persons when assessed in research settings. Although few studies have specifically included validated assessment tools targeting patient experience of respiratory health (e.g. the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ]), several investigators have included basic questionnaire data regarding patient self-report of symptoms. These symptoms, including cough and phlegm production, breathlessness, or wheeze have been found in greater than 30% of participants in HIV cohort studies[27–31]. Comparisons of symptoms between persons with HIV and those without have varied by setting and cohort[28, 32]. A large study sampling 3,872 participants from the U.S. multicenter MACS (Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study) and WIHS (Women’s Interagency HIV Study) cohorts found HIV to be an independent risk factor for cough, dyspnea, and wheeze among men in the MACS and for wheeze among women in WIHS[28]. A recent Cochrane meta-analysis and systematic review also found that people living with HIV are more likely than those without to experience respiratory symptoms. Cough was only significantly more common in association with HIV in populations without access to ART in the pooled estimates (possibly representing infectious etiologies), but breathlessness was more common in HIV-infected persons despite ART[33].

Chronic respiratory symptoms are not typically isolated findings. In the general population, respiratory symptoms have been associated both with poorer health-related quality of life and with underlying lung disease[34]. In persons with HIV, symptoms may similarly be attributable to chronic lung disease and have been associated with abnormal pulmonary function testing, including worse airway obstruction and decreased diffusing capacity[28, 30, 32, 35] as well as elevated pulmonary artery pressures on echocardiogram[36]. Additionally, respiratory symptoms and functional impairment are related, likely via linkage with underlying pulmonary disease. A commonly used and validated measure of functional capacity and physical endurance is the six-minute walk distance[37]. A study of US veterans with HIV found chronic cough to be independently associated with worse performance on six-minute walk testing, mediated by worse airflow limitation on pulmonary function testing[29]. Data from the same cohort found that chronic cough or phlegm and reduced six-minute walk distance were associated with radiographic emphysema among persons with HIV, but not in those who were not HIV-infected[38]. This differential symptom association in persons with early pulmonary disease has raised questions as to whether systemic and local inflammation in HIV lung disease is a unique contributor to respiratory symptoms and functional impairment.

There may also be associations of respiratory symptoms with quality of life and underlying pulmonary disease that are unique to HIV. A recent cross-sectional study of respiratory health status comparing SGRQ scores in HIV-infected ART-treated adults versus uninfected persons found that HIV infection was independently associated with worse respiratory health status[39]. Among persons with HIV, worse airflow obstruction, current smoking, and higher serum levels of the inflammatory marker IL-6 have been associated with worse SGRQ scores[40].

Pulmonary function testing is indicated as part of the initial evaluation for lung disease in persons with chronic respiratory symptoms and for monitoring of lung function in known lung disease. Of concern, despite the high prevalence of reported respiratory symptoms and participant experience of poor respiratory health status, diagnostic pulmonary testing of symptomatic individuals is infrequently performed in HIV clinics[28]. One study specifically identifying HIV-infected persons at increased risk for obstructive lung disease found that of those identified as high-risk (83% of whom were classified as such based on chronic respiratory symptoms, prior hospitalization for respiratory indication, or reported history of chronic lung disease), 90% had never had spirometry[41]. These findings suggest either that respiratory signs and symptoms are not ascertained in clinical care outside of the research setting, or that appropriate diagnostic testing is not readily pursued. Under-recognition of symptoms and disease in clinical practice may lead to missed opportunities for risk reduction and treatment among persons with HIV.

Non-Infectious Pulmonary Complications of HIV

Although the risk of acute pulmonary infections has decreased in the modern ART era, non-infectious pulmonary complications have taken on increased importance. HIV infection is an independent risk factor for several clinically important respiratory syndromes and diseases, including COPD, diffusing capacity impairment (a decrease in respiratory gas exchange), asthma, and pulmonary hypertension. These conditions are associated with increase in respiratory symptoms, decreased health-associated quality of life, increased healthcare costs, and increased mortality. Of note, primary lung cancer, which is beyond the scope of this review, is also more common among people living with HIV than uninfected persons, and is the leading cause of cancer-related death. HIV-associated lung cancer has been reviewed in detail elsewhere[42, 43].

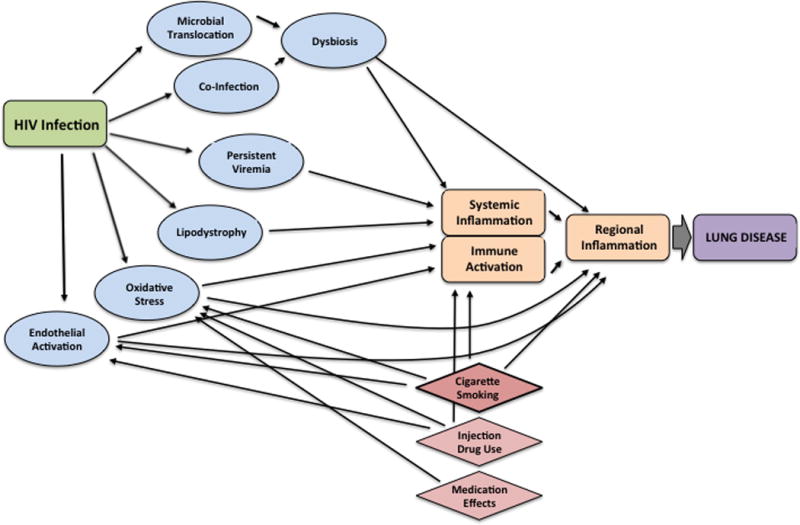

The degree to which these conditions are driven by specific HIV-related factors versus shared confounding risk factors remains unclear, but broad unifying syndromes inherent to acute and chronic HIV infection have been proposed as pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to pulmonary disease and symptoms. These include microbial translocation and resultant inflammation, chronic inflammation engendered by lymphocyte activation, macrophage/monocyte activation, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and changes to the host microbiome (Figure 1). Translational investigations assessing contributions of each of these inter-related processes to pulmonary disease and dysfunction will be reviewed.

Figure 1.

Mediators and confounders of the relationship between chronic HIV infection and lung disease

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Emphysema

COPD is a disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation and is classically described as resulting from two phenotypes or patterns of pathology: chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is characterized by airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion, clinically manifest by chronic cough and sputum production. Emphysema describes the loss of surface area and gas exchange capacity of lung alveoli; the destruction of lung tissue also contributes to physiologic abnormalities including decrease in lung elastic recoil with subsequent “air trapping” or dynamic hyperinflation. Both phenotypes of COPD are associated with breathlessness, decreased functional capacity, and decreased quality of life. COPD is diagnosed in the clinical setting by demonstrating airflow obstruction on spirometry. Emphysema also leads to gas diffusing impairment on pulmonary function testing, and may be recognized radiographically on chest imaging studies, including quantitative and qualitative interpretations of computed tomography (CT) scans. COPD is typically a smoking-related disease, but among persons with HIV, as in the general population[44], pulmonary function abnormalities and emphysema are also detected in non-smokers, suggesting additional mechanisms of pathophysiology that are independent of smoke exposure.

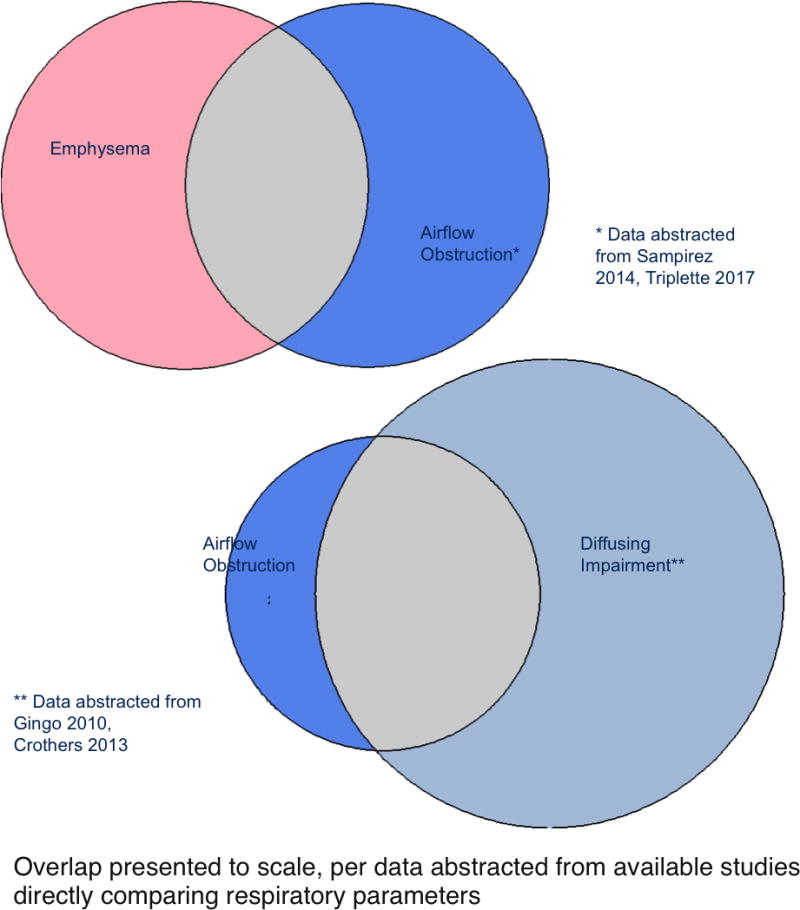

COPD is one of the better-characterized HIV-associated chronic lung diseases, with a long history in the epidemic. The first formal report of HIV-associated COPD in 1989 described premature bullous disease and emphysema in 42% of CT scans of persons with AIDS in a retrospective chart review[45]. A study published in 2000, including both pre- and post-ART participants, documented an increased frequency of radiographic emphysema in young persons infected with HIV (15%), including those who did not smoke tobacco, compared to matched controls (2%)[46]. Subsequent descriptive cohort studies have generally reported high proportion and rate of COPD, either from administrative data or self-report[4, 5] or as measured by spirometry[27, 30, 47–55], with prevalence reports of 3–27% for airflow obstruction and 10–37% for radiographic emphysema[46, 52, 56–58], depending on the classification methods used (Table 1). Some studies have reported lower prevalence of airflow obstruction, with percentages between 3–7% [31, 59–62], generally in cohorts with younger age and/or lower current or cumulative exposure to tobacco or biomass smoke, though not universally[31]. The few studies that have assessed overlap of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction find that emphysema is frequently independent of airflow obstruction[38, 52] (Figure 2), a finding that is also noted in general population studies and that suggests potential differences in pathophysiology[63]. It is worth noting that the presence or absence of radiographic emphysema is dependent on the method used for quantifying the CT data and the selection of a cutoff for ‘normal’ versus ‘abnormal;’ thus, studies including negative controls are particularly useful, but they are rare[38, 46].

Table 1.

Prevalence of and risk factors for COPD, radiographic emphysema, and diffusing impairment in HIV-infected persons

| COPD: Administrative Data/Self Report | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Prevalence | Smoking Status (%) | Age Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

ART (%) | Risk Factors for COPD | Notes | Study Design |

| Crothers 2006[4] | 1014 | 10% ICD-9 15% self-report |

Current: 36 Former: 40 Never: 24 |

55 (49–61) | 81.3 | Older age, bacterial pneumonia history, IDU, pack-years smoked, lower CD4 cell count (per 50 cell, in ICD-9 code analysis only) | VACS cohort | Prospective cohort, including HIV-negative controls |

| Gingo 2014[28] | MACS: 907 | 15.4% self-report | Current: 31 Former: 44 Never: 25 |

49.2 (8.8) | 78.4 | None identified | Included MACS and WIHS cohorts | Prospective cohort, including HIV- negative controls considered at high risk for contracting HIV |

| WIHS: 1405 | 8.1% self-report | Current: 39 Former: 29 Never: 32 |

44.4 (8.7) | 76.2 | Cocaine use, higher HIV viral load, pack-years smoked | |||

| Spirometry-defined COPD (FEV1/FVC < 0.7) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Prevalence | Smoking Status (%) | Age Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

ART (%) | Risk Factors for COPD | Notes | Study Design |

| George 2009[27] | 234 | 6.8 % | Current: 37 Former: 23 Never: 40 |

44.1 (9.4) | 83.3 | Older age, ART, bacterial pneumonia history, pack-years smoked | Single-center U.S. Pre-BD spirometry only |

Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Gingo 2010[48] | 167 | 21 % | Current: 53 Former: 23 Never: 24 |

46 (20–70) | 80.7 | ART, IDU, pack-years smoked | Single-center U.S. | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Onyedum 2010[60] | 100 | 3 % | Smokers excluded | Males 38.3 (9.5) Females 30.1 (5.7) |

ART excluded | NR | Single-center Nigeria Excluded pre-existing COPD, excluded pulmonary TB, excluded smokers and those exposed to biomass, excluded patients on ART. More stringent definition of COPD requiring FEV1 < 80% predicted. Pre-BD spirometry only |

Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls |

| Hirani 2011[49] | 98 | 16.3 % | Current: 21 Former: 34 Never: 44 |

45 (11) | 87.7 | Older age, IDU, history of PCP, pack-years smoked. | Single-center U.S. More stringent definition of COPD requiring FEV1 < 80% predicted. Pre-BD spirometry only |

Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Kristoffersen 2012[54] | 63 | 10 % 19 % after 4 years of follow-up |

Current: 48 | 43.3 (9.0) | 89 | NR | Single-center Denmark Pre-BD spirometry only |

Prospective cohort, HIV-infected only |

| Crothers 2013[30] | 300 | 18 % | Current: 47 Former: 27 Never: 26 |

54 (8) | 89 | NR | MACS/VACS cohort | Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls |

| Drummond 2013[98] | 316 | 16 % | Current: 84 Former: 9 Never: 6 |

48 (6.5) | 55 | NR | Cohort of injection drug users Pre-BD spirometry only |

Prospective cohort, including HIV-negative controls |

| Maddedu 2013[53] | 111 | 23.4 % | Current: 57 |

42 .3 (8.1) | 78.4 | Current smoking | Single-center Italy. Excluded: history of PCP, asthma, current alcohol or drug use | Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls matched on age, sex, smoking |

| Samperiz 2014[52] | 275 | 17.2 % | Current: 62 Former: 25 Never: 13 |

48.5 (6.6) | 95.6 | Older age, current smoking | Single-center Spain | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Nakamura 2014[55] | 49 | 10.2 % | Current: 45 Former: 16 Never: 39 |

40 median | 97.9 | NR | Single-center Japan. Pre-BD spirometry only |

Case-control, including HIV-negative controls |

| Akanbi 2015[51] | 356 | 15.4 % | Current: 4 Former: 17 Never: 79 |

44.5 (7.1) | 98 | Older age | Single-center Nigeria. 38% biomass exposure |

Cross-sectional, HIV-infected participants onl |

| Drummond 2015[35] | 908 | 27 % | Current: 68 Former: 19 Never: 13 |

50 (44–55) | 73 | Older age, current smoking, history of asthma, history of PCP | Multicenter U.S. Pre-BD spirometry only |

Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Makinson 2015[50] | 338 | 26 % | All current smokers per inclusion | 50 (46–53) | NR | Older age, lower BMI, HCV | Multicenter France | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Pefura-Yone 2015[59] | 461 | 2.2 % | Current: 5 Former: 8 Never: 87 |

42 .6 (10.1) | 85 | Alcohol use, lower BMI, history of TB | Single-center Cameroon TB 42 % Biomass exposure 38% |

Case-control, including HIV-negative controls matched on age and sex |

| Nimmo 2015[61] | 218 | 6.8 % | Current: 23 Former: 24 Never: 53 |

46.7 (9.8) | 84.4 | NR | Single-center U.K. Study designed to assess lower airway bacterial colonization |

Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Kunisaki 2015[62] | 989 | 5.5 % | Current: 28 Former: 11 Never: 61 |

36 (30–44) | 0 | Older age, current smoking | Multinational Inclusion: CD4>500, ART naïve. COPD varied by region |

Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Risso 2017[41] | 571 | 9 % | Current: 51 Former: 21 Never: 28 |

48.3 (9.9) | 93.5 | Older age, lower BMI, lower CD4 cell count, pack-years smoked | Single-center France. Only those with positive respiratory screen advanced to full PFTs | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Radiographic emphysema | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Prevalence** | Smoking Status (%) | Age Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

ART (%) | Risk Factors for Emphysema | Notes | Study Design |

| Diaz 2000[46] | 114 | 15% Semi-quantitative | Current: 60 | 34.1 (22.8–63.4) | NR | NR | Included patients from 1994–1997 | Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls matched on age & smoking history |

| Samperiz 2014[52] | 275 | 10.5 % Quantitative | Current: 61.5 Former: 25.1 Never: 13.5 |

48.5 (6.6) | 95.6 | Quantitative: lower BMI, pack-years smoked, stage C HIV | Single-center Spain | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| 37.7 % Qualitative | Qualitative: Current smoking, lower CD4 cell count | |||||||

| Guaraldi 2014[56] | 1446 | 19% Semi-quantitative | Current: 40 | 48.4 (7.6) | ART use was inclusion criteria | Older age, current smoking, IDU, leukocytosis | Single Center Italy | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Leader 2016[57] | 510 | 25.1% Quantitative (>2.5% voxels below -950 HU) | Current: 64 Former: 21 Never: 15 |

48.9 (9.5) | 69 | Older age, current smoking, lower FEV1/FVC | Multicenter U.S. | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Triplette 2017[38] | 164 | 31% Semi-quantitative (cutoff of >10% emphysema) | Current: 63 Former: 21 Never : 16 |

55 (49–59) | 71 | CD4/CD8 <0.4 | Subset of VACS cohort; specifically evaluating CD4/CD8 ratio in emphysema | Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls |

| Diffusing impairment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Prevalence of diffusing impairment | DLCO % predicted Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

Smoking Status (%) | Age Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

ART (%) | Risk Factors for Diffusing Impairment | Notes | Study Design |

| Gingo 2010[48] | 167 | 64.1% (< 80% predicted) | 72.3 (17.6) | Current: 53 Former: 23 Never: 24 |

46 (20–70) | 80.7 | Ever smoking, PCP prophylaxis | Single-center U.S. | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Kristoffersen 2012[54] | 63 | 42 % (< 80% predicted) | 83.3 (15.5) | Current: 48 | 43.3 (9.0) | 89 | NR | Single-center Denmark. DLCO not corrected for hemoglobin |

Prospective cohort, HIV-infected only |

| Crothers 2013[30] | 300 | 30 % (< 60% predicted) |

69.0 (19) | Current: 47 Former: 27 Never: 26 |

54 (8) | 89 | NR | MACS/VACS cohort |

Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls |

| Fitzpatrick 2013[66] | 63 | NR | 65.5 (13.7) | Current: 46 Former: 29 Never: 25 |

49.1 (8.9) | 81 | Cocaine use, pneumonia history (bacterial or PCP) | WIHS cohort | Cross-sectional, including HIV-negative controls considered high risk for contracting HIV |

| Samperiz 2014[52] | 275 | 52.2 % (< 80% predicted) |

79.7 (16.5) | Current: 62 Former: 25 Never: 13 |

48.5 (6.6) | 95.6 | Lower BMI, current smoking, advanced HIV [C stage] | Single-center Spain | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Makinson 2015[50] | 301 | NR | 68 (59–83) | All current smokers per inclusion | 50 (46–53) | NR | NR | Multicenter France | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

| Leung 2016[99] | 345 | NR | 75.2 (65.7–87.2) | Current: 48 Former: 29 Never: 19 |

49 (45–53) | 100 | NR | Single-center Italy | Cross-sectional, HIV-infected only |

ART: anti-retroviral therapy; IDU: injection drug use; IQR: interquartile range; MACS: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study;

VACS: Veterans Aging Cohort Study; WIHS: Women’s Interagency HIV Study

ART: anti-retroviral therapy; BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; HCV: hepatitis C virus; IQR: interquartile range; MACS: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study; NR: not reported; PCP: Pneumocystis pneumonia;

PFTs: pulmonary function tests; TB: tuberculosis; VACS: Veterans Aging Cohort Study; WIHS: Women’s Interagency HIV Study

ART: anti-retroviral therapy; BMI: body mass intex; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity;

IDU: injection drug use; IQR: interquartile range; NR: not reported; PFTs: pulmonary function tests; TB: tuberculosis;

VACS: Veterans Aging Cohort Study

Emphysema definitions vary across studies, but in general can be determined qualitatively (e.g. individual radiologist impression) or quantitatively (e.g. computerized calculations of low lung density). Semi-quantitative methods involve ranking a score for severity based on visual assessment.

ART: anti-retroviral therapy; BMI: body mass index; DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; IQR: interquartile range; MACS: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study; PCP: Pneumocystis pneumonia; VACS: Veterans Aging Cohort Study;

WIHS: Women’s Interagency HIV Study

Studies cited in the tables within Table 1 were identified via database search via PubMed (MEDLINE) with combinations of search terms including “HIV,” “AIDS,” “COPD,” “emphysema,” “ airflow obstruction,” “spirometry,” “asthma,” “diffusing capacity,” “diffusion capacity,” “diffusing impairment,” “diffusion impairment,” and “gas transfer.” References of references were then reviewed to identify additional studies. Tables updates as of August 2017.

Figure 2.

Overlap of emphysema, airflow obstruction, and diffusing impairment in HIV-infected persons with respiratory abnormalities

Despite the strong association with smoking in the HIV-uninfected population, HIV-infected persons without smoke exposure also exhibit fixed airflow obstruction[48], and multiple studies have identified HIV infection as an independent risk factor for prevalent COPD[4, 5, 28, 55], radiographic emphysema[64], incident diagnosis of COPD[5], and more frequent COPD exacerbations[65]. These data suggest that HIV infection contributes to COPD independent of usual pathways.

Clinically identifiable risk factors for COPD among individuals with HIV are frequently the same as those in the general population (Table 1). Across most cohorts, older age and cigarette smoking remain independent risk factors for COPD or airflow obstruction[27, 35, 41, 48–53, 62]. Other identified independent factors in some groups have included include low body mass index (BMI)[41, 50, 59], injection drug use[48, 49], history of bacterial pneumonia[27] or colonization[61], Pneumocystis pneumonia[35, 49, 66], pulmonary tuberculosis[52, 59], and co-infection with infectious hepatitis C[41, 50, 66]. The contribution of hepatitis C to airflow obstruction beyond injection drug use remains unclear, and not all studies find an independent effect[67].

HIV-specific risk factors such as ART use, CD4 cell count, and HIV viral levels have been examined in most studies of HIV and pulmonary function. Two single-center cross-sectional studies found a positive association between ART use and risk of spirometry-defined COPD. The prevalence of ART prescription in these studies was approximately 80%, and CD4 cell count and HIV viral load were not associated with COPD[27, 48]. A recent study assessed pulmonary function trajectories in the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial[68], an international prospective trial randomizing ART initiation to immediate versus deferred (until CD4 cell count < 350 cells/uL or AIDS developed) in HIV-infected individuals naïve to ART with CD4 cell counts > 500 cells/uL[69]. In this trial, there were no differences in spirometry changes or respiratory symptoms between groups, supporting that ART does not directly contribute to worse pulmonary function. Given the trial’s enrollment criteria, however, deleterious effects of ART attributable to reconstitution of the immune system in persons with lower nadir CD4 counts or higher viral loads cannot be ruled out.

Associations with CD4 cell count have been reported in several studies[30, 41, 51, 64]. In one report, lower CD4 count was linearly associated with increased odds of COPD[41], while in the others, very low CD4 cell count (< 200 cells/uL) were required to demonstrate associations with airflow obstruction[30, 51]. All of these cohorts reported high rates of ART prescription (89–98%). A study evaluating risk of emphysema found a nadir CD4 cell count < 200 cells/uL significantly associated with risk of radiographic emphysema[64].

Regarding viral load, one study in a cohort of high-risk injection drug uses found that high HIV viral RNA level (>200,000 copies/mL) was associated with obstructive lung disease when comparing to HIV-uninfected participants[47]. Other studies assessing HIV viral load did not use the same stratification methods in analyses, and findings are therefore difficult to compare. Perhaps in contrast to the other reported findings, a study evaluating self-report of COPD exacerbation among injection drug users with spirometry-confirmed COPD found that HIV-infected persons with higher CD4 cell counts (> 350 cells/uL) or undetectable HIV viral levels had increased odds of exacerbation when compared to uninfected controls, while those with lower CD4 cell counts or detectable viremia did not[65]. The reasons for these findings are not clear.

Finally, a recent HIV emphysema study found that low CD4/CD8 ratio (<0.4), associated with chronic inflammation and T-cell activation in HIV[70], was independently associated with higher odds of emphysema when compared to a high CD4/CD8 ratio (>1.0)[58]. Interestingly, a small translational study also found lower CD4/CD8 ratio in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of HIV-infected patients compared to controls[71].

The contradictory results about the impact of HIV-associated variables are likely secondary to differences among cohorts in duration of HIV, level of HIV control, and alternate risk factors, as well as varying methods of analyzing data. Additionally, potentially pertinent contributors such as true nadir CD4 cell counts, periods of ART adherence/non-adherence, and duration of HIV are difficult to capture retrospectively, and may account for unmeasurable differences among participants and between cohorts.

Mechanistic contributors to COPD including oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, cellular senescence, immune activation, and endothelial dysfunction have been evaluated in a smaller number of translational studies. Oxidative stress is a feature of both HIV infection[72] and COPD[73], and has been assessed in basic and translational studies[74–76]. For example, one translational study measuring decreased glutathione, a marker of oxidative stress, in bronchoalveolar fluid collected from persons with and without HIV found HIV infection without ART (compared to HIV-uninfected) to be a risk factor for oxidative stress[77]. How this finding relates to pulmonary function is not yet clear. Systemic inflammation, immune activation, and cellular senescence may be linked in HIV[78–80], with mechanisms including low level HIV viral persistence[81, 82], microbial translocation[83, 84], or viral co-infection (CMV[85], EBV[86], hepatitis[87]) as drivers of T-cell or B-cell pattern recognition and stimulation. Elaboration of inflammatory mediators may contribute to COPD; therefore, these links have been assessed in translational studies, below.

Given that COPD in the general population has been associated with dysfunctional systemic inflammation[88, 89] that also typifies chronic HIV[90–92], a relationship between the two has also been sought as a possible mechanism of HIV-associated COPD. One cross-sectional study in HIV found increases in peripheral IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) with airflow obstruction, while IL-8 was not associated; additionally, surface markers of T-cell activation were associated with abnormal spirometry[93]. IL-6 was similarly associated in another cohort, while IL-8 and TNF-alpha were not[94]. Cellular senescence, also a feature of chronic HIV infection and inflammation, may be important in HIV-related COPD. Shorter telomere length was seen in individuals with worse spirometry in one cross-sectional study[93]. T-cell surface markers of replicative senescence in the same study were paradoxically associated with better spirometry,[93] a phenomenon potentially explained by unique effects of HIV infection on terminal differentiation of effector memory T cells[95]. More recently, investigations have examined monocyte and macrophage activation. The circulating monocyte marker sCD163 was increased in individuals with worse spirometry,[94] and sCD14 was associated with greater risk of radiographic emphysema in persons with HIV, but not in HIV-uninfected persons[64]. High levels of sCD163 have also been associated with incident chronic lung disease in a prospective cohort study of HIV-infected persons; notably, the association between sCD163 and chronic lung disease was strongest in nonsmokers[96] . Similarly, circulating endothelin-1, a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction, was a significant biomarker for airflow obstruction in persons with HIV, but had no relationship to pulmonary function in HIV-uninfected individuals[94]. Taken together, these studies suggest an interaction between monocyte markers, endothelial dysfunction, and other inflammatory pathways and risk of COPD that may be unique to HIV.

Few studies have examined lung function trajectory among persons with HIV, and decline of spirometry measures of lung function has been performed only over relatively short-term follow-up periods[54, 94, 97, 98]. Lung function normally declines with increasing age, but whether lung function declines more rapidly among persons with HIV than those without has not been proven. One prospective study in a high-risk cohort of injection drug users enrolling both HIV-infected and uninfected individuals found greater decline among individuals with the highest threshold of viral load (> 75,000 copies/mL) and the lowest CD4 cell counts (< 100 cells/uL) when compared to uninfected persons[98]. Certain clinical risk factors beyond HIV-specific variables have been associated with worse trajectory. One study assessing the qualitative assessment of radiographic emphysema over several years of follow-up found that 17% of participants progressed, with risk factors for progression including baseline presence of combined centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema (present in 23% of the cohort), worse DLco, high pack-years smoked, male sex, and lower BMI[99]. While single-center cross-sectional studies found associations between ART use and COPD, a large prospective study evaluating pulmonary function decline in association with initiation of ART found no difference in rate of lung function decline between people randomized to initiate ART at CD4 cell counts > 500 cells/uL versus at CD4 cell counts < 350 cells/uL[69].

Several mechanisms might contribute to lung function decline in HIV. One study evaluating biomarkers of inflammation, monocyte activation, and endothelial dysfunction in HIV-infected and uninfected participants found that endothelin-1 independently predicted worse airflow obstruction over time in HIV-infected persons; other biomarkers were not significantly associated with decline[94]. Additional research in large cohorts including HIV-infected and uninfected participants, with sustained longitudinal follow-up, is necessary to define the natural history of airflow obstruction in HIV-infected persons and to define modifiable risk factors to reduce the incidence and progression of COPD.

Diffusing Impairment

A common measure of pulmonary function, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), is a sensitive surrogate for gas exchange across the alveolar capillary membrane, and is associated with functional impairment and with clinical symptoms, including breathlessness and dyspnea on exertion. Reduction of the DLCO may be secondary to destruction of the alveolar interface (from emphysema/COPD), scarring of the interface (interstitial lung disease or fibrosis), or pulmonary vascular disease/cardiopulmonary dysfunction. Diffusing capacity is not always measured as part of routine pulmonary function testing or in the research setting, thus fewer data are available for DLCO than for spirometry. When DLCO measures have been obtained in HIV cohorts, DLCO deficits are by far the most common pulmonary function abnormality and are in some cases severely abnormal[30, 48, 52, 54, 66, 94]. HIV has been shown to be an independent risk factor for DLCO impairment in cohorts including HIV-infected and uninfected participants in both the pre- and post-ART eras[30, 66]. Interestingly, while in many cases DLCO impairment is seen in association with abnormal spirometry or radiographic emphysema[30, 66, 99, 100] (and therefore likely to represent lung disease), significant DLCO impairment is also found with normal spirometry, suggesting another pathophysiology driving gas exchange impairment in these participants[30, 48, 66, 97](Figure 2). Certain cohorts have found diffusing impairment to correlate with abnormal echocardiogram findings, with increased tricuspid regurgitant velocity (TRV) suggesting elevated pulmonary artery pressures or cardiopulmonary dysfunction as a contributor[36, 100], but a significant portion of HIV-infected individuals have neither COPD nor cardiac dysfunction to explain their DLco impairment.

Several characteristics have been found to define diffusing impairment in HIV infected persons. These include expected pulmonary risk factors, such as smoking, low BMI[30, 48, 52] and injection drug use, in addition to HIV-specific risk factors, including CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/uL[30, 66] and CDC stage C HIV[52]. A study that stratified by smoking status (ever-smokers versus non-smokers) found that among smokers, DLCO was most strongly associated with airflow obstruction and radiographic emphysema, whereas in non-smokers, forced vital capacity and changes in sputum cell counts were associated with DLco, supporting different mechanisms of diffusing impairment between groups[100]. Finally, blood markers of diffusing impairment have been evaluated in two studies. In one study including only HIV-infected persons, serum IL-6 and CRP were increased in individuals with worse DLCO, suggesting a Th1 inflammatory component[93]. Another study including both HIV-infected and uninfected participants also found that higher IL-6 and TNF-alpha were independently associated with worse DLCO. Additionally, markers of monocyte activation (sCD163, IL2 receptor), microbial translocation (lipopolysaccharide), and endothelial dysfunction (endothelin-1) were linked to lower DLco in HIV-infected individuals[94]. The trajectory of DLCO over time in HIV-infected persons and the degree to which it may be affected by modifiable risk factors remain unclear. One study found diffusing capacity in HIV-infected persons to decline over time[54], while another found a paradoxical increase in DLCO over time[94], though the latter was possibly secondary to regression to the mean. This study did not find significant differences in DLCO trajectory between HIV-infected and –uninfected groups, but was performed over a limited period of follow-up and was likely underpowered to detect such differences.

Asthma

Asthma is the most frequent chronic lung disease in the United States, but compared to the data for COPD in HIV, there are far fewer data regarding asthma in adults with HIV. One single-center U.S. study found a very high prevalence of doctor-diagnosed asthma (20.6%) in HIV-infected adults[101]. Another report in the multicenter MACS and WIHS cohorts found that asthma was the most frequent self-reported respiratory diagnosis in each group (13.5% prevalence in MACS and 22.9% in WIHS), although no significant difference in prevalence or incidence of diagnosis was found between HIV-infected and uninfected participants[28]. Administrative data from Canada assessing multimorbidity in HIV (irrespective of pre- or post-ART) found a prevalence of asthma claims of 12.7%[102]. In contrast, a cross-sectional study performed in Zimbabwe found a much lower burden of self-reported asthma (4.3%)[103]. Information on risk factors was not available in this study.

Spirometry findings supporting asthma include reversible airflow obstruction evidenced by improvement in airflow in response to bronchodilator, or airway hyper-reactivity detected on bronchoprovocation testing with a bronchial irritant such as methacholine. The U.S. single-center study referenced above found bronchodilator reversibility in 9% of HIV-infected participants[101]. Another cross-sectional study including HIV-infected and uninfected men found a 26.2% prevalence of airway hyper-reactivity in HIV-infected men (versus 14.4% of uninfected controls)[104].

Clinical factors associated with asthma in HIV-infected persons have been assessed. These risks include innate factors such as female sex and family history of asthma, as well as potentially modifiable exposures such as prior history of pneumonia and obesity [28, 101]. Interestingly, higher BMI was also associated with increased asthma risk, and there appears to be an asthma phenotype of obese HIV-infected females who are at risk for adult-onset asthma. ART use was found to be associated with lower risk of asthma in one study, but data are not conclusive[101]. Biomarkers that have been associated with asthma in HIV include atopic markers such as sputum eosinophils[101] and IgE[104], and inflammatory mediators IL-4 and RANTES[101]. Non-traditional markers associated with chronic HIV infection[101] and adipose-related inflammatory mediators such as adiponectin are also linked to asthma in HIV infection[105]. Adipokines have been related to obesity-related asthma in the general population, and the relationship between adipokines and HIV-associated lipodystrophy suggests possible disease mechanisms which may been enriched in those with HIV[106].

Pulmonary Hypertension and Cardiac Dysfunction

Pulmonary hypertension has been recognized as a complication of HIV since the pre-ART era, and prevalence estimates suggest that frequency has not significantly changed following ART, remaining at approximately 0.5% of HIV-infected persons[107, 108]. Cohort studies in the ART era suggest that elevated pulmonary arterial pressures assessed via echocardiogram were much more common, with clinically significant elevations in the tricuspid regurgitant velocity (TRV) or pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) in 8–35% of participants[36, 109, 110]. HIV was found to be an independent risk factor for elevated PASP in one of these studies, with sevenfold greater odds of PASP elevation in HIV-infected participants[109]. The significance of elevated pulmonary artery pressures on echocardiogram is not known, and it is unclear if this finding confers a greater risk of developing true pulmonary hypertension in the future.

Reports of association of HIV-related factors with pulmonary hypertension are conflicting, with some studies reporting association with ART or low CD4 cell count (< 200 cells/uL) while others do not[36, 107, 109]. The molecular mechanisms of pulmonary hypertension in HIV remain under investigation, having been linked to viral factors directly via HIV viral proteins contributing to pathogenesis[111–113], and also indirectly with markers of inflammation (IL-6 and interferon-gamma)[36] and endothelial dysfunction (asymmetric dimethylarginine[114] and endothelin-1[115, 116]) relating to elevated pulmonary pressures on right heart catheterization or echocardiogram. A recent study of both HIV-infected individuals and a simian immunodeficiency virus-infected non-human primate model found a relationship between glutaminolysis and pulmonary hypertension[117]. Other work in animal models and cell lines implicates interactions of HIV and drugs of abuse such as cocaine and opiates in pulmonary hypertension[118–120].

Despite the increased relative risk of pulmonary hypertension in this population, the absolute risk of developing Group 1 pulmonary hypertension remains relatively small. Much more common, and thus likely representing a much greater burden of symptoms, is cardiac dysfunction, including left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction. While “heart failure” may not typically be considered a pulmonary disease, the symptoms of cardiac dysfunction overlap considerably with pulmonary abnormalities, and shared risk factors and pathogenesis may underlie cardiac and pulmonary complaints. A study assessing the overlap between cardiac dysfunction and pulmonary function in HIV-infected persons found that elevated PA systolic pressure and tricuspid regurgitant velocity were associated with worse airflow obstruction and worse diffusing capacity, and participants with elevated tricuspid regurgitant velocity had increased respiratory symptoms[36]. In HIV-uninfected persons, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction has been found in association with COPD, and is associated with worse functional capacity (including 6MWD)[121], and heart failure syndromes in general are associated with worse diffusing impairment[122], the most common of the HIV-associated pulmonary function abnormalities.

Congestive heart failure is a more frequent diagnosis among persons with HIV than in uninfected controls[123]. A retrospective cohort study from 2011 involving veterans enrolled in the VACS and the Lung Health Study of Veterans found an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.8 for incident heart failure during approximately 7 years of follow up. In this cohort, HIV RNA of > 500 copies/mL was associated with higher risk of heart failure[124]. A follow-up large study of administrative VA data evaluating 98,015 participants without baseline CVD again found an increased risk of incident heart failure diagnoses in association with HIV, with significantly increased hazard ratios for both preserved and reduced ejection fractions. HIV RNA of > 500 copies/mL was associated with increased risk of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and CD4 cell count < 200 cells/uL (versus >= 500) was associated with increased risk of both HFrEF and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Participants younger than age 40 at baseline had a particularly pronounced risk of incident HF diagnosis[125].

A large ART-era meta-analysis published in 2013, including 11 studies (mean pooled age of participants 42, 21% with hypertension and 23% with active smoking), found reports of LV systolic dysfunction of around 8% and LV diastolic dysfunction around 43%. Predictors of systolic dysfunction in this analysis included elevated high-sensitivity CRP, active tobacco smoking, and prior myocardial infarction. Predictors of diastolic dysfunction included older age and HTN. HIV-associated risk factors such as CD4 cell count and HIV RNA were not identified as predictors, but most (98%) participants were on ART with undetectable HIV RNA (74%)[126].

Therapies for Lung Diseases in HIV

Ideal therapies for chronic lung diseases such as COPD, asthma, and pulmonary hypertension in HIV are largely unknown. The majority of trials in these diseases have not included HIV-infected individuals. Standard therapies are therefore generally recommended, but specific concerns exist in the HIV-infected population. In particular, commonly used therapies such as inhaled corticosteroids for COPD and asthma may have more side effects in those with HIV including increased adrenal suppression from interactions with certain antiretroviral agents, mainly ritonavir and cobicistat[127]. Additionally, inhaled corticosteroids are associated with increased risk of bacterial pneumonia[128] and tuberculosis[129–131] when used in persons with chronic lung disease in the general population; these concerns are of particular relevance to individuals with existing immune suppression, particularly in regions with higher tuberculosis burden. There has been a single published study investigating treatment of COPD specifically in HIV-infected individuals[97]. This study was a small randomized pilot study of rosuvastatin in persons with HIV and airway obstruction or DLco impairment. It demonstrated a trend of slower decline in airway obstruction and an increase in DLco after 24 weeks of treatment when compared to placebo, possibly mediated via pleotropic anti-inflammatory effects, including effects on endothelial function[97] . Data in larger cohorts are necessary to confirm this finding.

The greatest opportunity for modification of respiratory disease in the HIV-infected population likely lies in intensifying focus on smoking cessation. In industrialized areas, smoking prevalence among persons with HIV is double that in the general population[132]. Large epidemiologic study estimating attributable mortality associated with smoking in European and North American cohorts suggest that smoking may in fact cause more lost life years than HIV infection itself[133, 134]. Quit rates for smokers are significantly less among persons with HIV[132], but the majority of HIV-infected individuals express and interest in quitting and have made at least one quit attempt[135, 136]. For HIV-infected persons who smoke, supporting their efforts to quit smoking[137] must be a priority for improving lung health, as well as general health.

Areas of uncertainty and opportunity

Despite an increased recognition of chronic pulmonary disease and symptoms in individuals with HIV infection, there are still many unanswered questions. First, limited longitudinal data exist describing the trajectory of pulmonary function, functional capacity, and mortality among persons with and at risk for lung disease over time. Current data suggest that persons with HIV, particularly those with poor virologic control, experience more rapid decline over time[98]. Longer-term prospective data in larger, contemporary cohorts enrolling both infected and well-matched uninfected individuals with and without typical pulmonary disease risk factors are needed to 1) better define the course of disease, 2) identify predictors of progressive disease and 3) identify and confirm targets to reduce the risk and progression of disease. Additionally, despite the shared risk factors and physiologic intersection between cardiac dysfunction and pulmonary disease in HIV, and the enhanced focus on multimorbidity in chronically infected patients, very few studies in the literature have directly assessed the overlap between cardiac dysfunction and pulmonary disease and outcomes among persons with HIV. Finally, for persons who are diagnosed with chronic lung disease or respiratory symptoms, aside from the salutary effects of smoking cessation[138], very little data are available regarding clinical care and therapy. These gaps will be very important to address to improve the respiratory health of people living longer with HIV in the current era.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: K24 HL123342 (AM), R01 HL096453 (KMK)

References

- 1.Marcus JL, Chao CR, Leyden WA, Xu L, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Klein DB, et al. Narrowing the Gap in Life Expectancy Between HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Individuals With Access to Care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(1):39–46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PloS one. 2013;8(12):e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Justice AC, Braithwaite RS. Lessons learned from the first wave of aging with HIV. Aids. 2012;26(Suppl 1):S11–18. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283558500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crothers K, Butt AA, Gibert CL, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Crystal S, Justice AC. Increased COPD among HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative veterans. Chest. 2006;130(5):1326–1333. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crothers K, Huang L, Goulet JL, Goetz MB, Brown ST, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183(3):388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0836OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gingo MR, Balasubramani GK, Kingsley L, Rinaldo CR, Jr, Alden CB, Detels R, et al. The impact of HAART on the respiratory complications of HIV infection: longitudinal trends in the MACS and WIHS cohorts. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan JH, Moore RD, Keruly JC, Chaisson RE. Effect of antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of bacterial pneumonia in patients with advanced HIV infection. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000;162(1):64–67. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9904101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohli R, Lo Y, Homel P, Flanigan TP, Gardner LI, Howard AA, et al. Bacterial pneumonia, HIV therapy, and disease progression among HIV-infected women in the HIV epidemiologic research (HER) study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006;43(1):90–98. doi: 10.1086/504871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry SA, Fleishman JA, Moore RD, Gebo KA, Network HIVR Trends in reasons for hospitalization in a multisite United States cohort of persons living with HIV, 2001–2008. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(4):368–375. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318246b862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, Van Handel MM, Stone AE, LaFlam M, et al. Vital Signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV–United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1113–1117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown J, Lipman M. Community-Acquired Pneumonia in HIV-Infected Individuals. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16(3):397. doi: 10.1007/s11908-014-0397-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afessa B, Green B. Bacterial pneumonia in hospitalized patients with HIV infection: the Pulmonary Complications, ICU Support, and Prognostic Factors of Hospitalized Patients with HIV (PIP) Study. Chest. 2000;117(4):1017–1022. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen C, Simonsen L, Sample J, Kang JW, Miller M, Madhi SA, et al. Influenza-related mortality among adults aged 25–54 years with AIDS in South Africa and the United States of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(7):996–1003. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters PJ, Skarbinski J, Louie JK, Jain S, New York City Department of Health Swine Flu Investigation T. Roland M, et al. HIV-infected hospitalized patients with 2009 pandemic influenza A (pH1N1)–United States, spring and summer 2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 1):S183–188. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheth AN, Althoff KN, Brooks JT. Influenza susceptibility, severity, and shedding in HIV-infected adults: a review of the literature. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;52(2):219–227. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Althoff KN, Anastos K, Nelson KE, Celentano DD, Sharp GB, Greenblatt RM, et al. Predictors of reported influenza vaccination in HIV-infected women in the United States, 2006–2007 and 2007–2008 seasons. Prev Med. 2010;50(5–6):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durham MD, Buchacz K, Armon C, Patel P, Wood K, Brooks JT, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination rates in the HIV outpatient study-United States, 1999–2013. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;60(6):976–977. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albalak R, O’Brien RJ, Kammerer JS, O’Brien SM, Marks SM, Castro KG, et al. Trends in tuberculosis/human immunodeficiency virus comorbidity, United States, 1993–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2443–2452. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones JL, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, DeCock KM, Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIVDG HIV-associated tuberculosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. The Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Group. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(11):1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suthar AB, Lawn SD, del Amo J, Getahun H, Dye C, Sculier D, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of tuberculosis in adults with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan JE, Hanson D, Dworkin MS, Frederick T, Bertolli J, Lindegren ML, et al. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated opportunistic infections in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 1):S5–14. doi: 10.1086/313843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarcz L, Chen MJ, Vittinghoff E, Hsu L, Schwarcz S. Declining incidence of AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses: results from 16 years of population-based AIDS surveillance. AIDS. 2013;27(4):597–605. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b0fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, Graviss E, Hamill R, Brandt ME, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992–2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(6):789–794. doi: 10.1086/368091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masannat FY, Ampel NM. Coccidioidomycosis in patients with HIV-1 infection in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;50(1):1–7. doi: 10.1086/648719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baddley JW, Sankara IR, Rodriquez JM, Pappas PG, Many WJ., Jr Histoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients in a southern regional medical center: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myint T, Al-Hasan MN, Ribes JA, Murphy BS, Greenberg RN. Temporal trends, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of histoplasmosis in a tertiary care center in Kentucky, 2000 to 2009. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(2):100–105. doi: 10.1177/2325957413500535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George MP, Kannass M, Huang L, Sciurba FC, Morris A. Respiratory symptoms and airway obstruction in HIV-infected subjects in the HAART era. PloS one. 2009;4(7):e6328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gingo MR, Balasubramani GK, Rice TB, Kingsley L, Kleerup EC, Detels R, et al. Pulmonary symptoms and diagnoses are associated with HIV in the MACS and WIHS cohorts. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2014;14:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campo M, Oursler KK, Huang L, Goetz MB, Rimland D, Hoo GS, et al. Association of chronic cough and pulmonary function with 6-minute walk test performance in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(5):557–563. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crothers K, McGinnis K, Kleerup E, Wongtrakool C, Hoo GS, Kim J, et al. HIV infection is associated with reduced pulmonary diffusing capacity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(3):271–278. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a9215a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Q, Carruthers S, McIvor A, Smaill F, Thabane L, Smieja M. Effect of smoking on lung function, respiratory symptoms and respiratory diseases amongst HIV-positive subjects: a cross-sectional study. AIDS research and therapy. 2010;7:6–16. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drummond MB, Kirk GD, Ricketts EP, McCormack MC, Hague JC, McDyer JF, et al. Cross sectional analysis of respiratory symptoms in an injection drug user cohort: the impact of obstructive lung disease and HIV. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown J, Roy A, Harris R, Filson S, Johnson M, Abubakar I, et al. Respiratory symptoms in people living with HIV and the effect of antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2017;72(4):355–366. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voll-Aanerud M, Eagan TM, Plana E, Omenaas ER, Bakke PS, Svanes C, et al. Respiratory symptoms in adults are related to impaired quality of life, regardless of asthma and COPD: results from the European community respiratory health survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:107. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drummond MB, Huang L, Diaz PT, Kirk GD, Kleerup EC, Morris A, et al. Factors associated with abnormal spirometry among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2015;29(13):1691–1700. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris A, Gingo MR, George MP, Lucht L, Kessinger C, Singh V, et al. Cardiopulmonary function in individuals with HIV infection in the antiretroviral therapy era. AIDS. 2012;26(6):731–740. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835099ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, Hernandes NA, Mitchell KE, Hill CJ, et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1447–1478. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Triplette M, Attia E, Akgun K, Campo M, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Pipavath S, et al. The Differential Impact of Emphysema on Respiratory Symptoms and 6-Minute Walk Distance in HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):e23–e29. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown J, McGowan JA, Chouial H, Capocci S, Smith C, Ivens D, et al. Respiratory health status is impaired in UK HIV-positive adults with virologically suppressed HIV infection. HIV Med. 2017 doi: 10.1111/hiv.12497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung JM, Liu JC, Mtambo A, Ngan D, Nashta N, Guillemi S, et al. The determinants of poor respiratory health status in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(5):240–247. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Risso K, Guillouet-de-Salvador F, Valerio L, Pugliese P, Naqvi A, Durant J, et al. COPD in HIV-Infected Patients: CD4 Cell Count Highly Correlated. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0169359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sigel K, Pitts R, Crothers K. Lung Malignancies in HIV Infection. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;37(2):267–276. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1578803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiderlen TR, Siehl J, Hentrich M. HIV-Associated Lung Cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40(3):88–92. doi: 10.1159/000458442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamprecht B, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gudmundsson G, Welte T, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, et al. COPD in never smokers: results from the population-based burden of obstructive lung disease study. Chest. 2011;139(4):752–763. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuhlman JE, Knowles MC, Fishman EK, Siegelman SS. Premature bullous pulmonary damage in AIDS: CT diagnosis. Radiology. 1989;173(1):23–26. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.1.2781013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz PT, King MA, Pacht ER, Wewers MD, Gadek JE, Nagaraja HN, et al. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary emphysema among HIV-seropositive smokers. Annals of internal medicine. 2000;132(5):369–372. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drummond MB, Kirk GD, Astemborski J, Marshall MM, Mehta SH, McDyer JF, et al. Association between obstructive lung disease and markers of HIV infection in a high-risk cohort. Thorax. 2012;67(4):309–314. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gingo MR, George MP, Kessinger CJ, Lucht L, Rissler B, Weinman R, et al. Pulmonary function abnormalities in HIV-infected patients during the current antiretroviral therapy era. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;182(6):790–796. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1858OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirani A, Cavallazzi R, Vasu T, Pachinburavan M, Kraft WK, Leiby B, et al. Prevalence of obstructive lung disease in HIV population: a cross sectional study. Respiratory medicine. 2011;105(11):1655–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makinson A, Hayot M, Eymard-Duvernay S, Quesnoy M, Raffi F, Thirard L, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed COPD in a cohort of HIV-infected smokers. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(3):828–831. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00154914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akanbi MO, Taiwo BO, Achenbach CJ, Ozoh OB, Obaseki DO, Sule H, et al. HIV Associated Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Nigeria. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015;6(5) doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samperiz G, Guerrero D, Lopez M, Valera JL, Iglesias A, Rios A, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for pulmonary abnormalities in HIV-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2014;15(6):321–329. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madeddu G, Fois AG, Calia GM, Babudieri S, Soddu V, Becciu F, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an emerging comorbidity in HIV-infected patients in the HAART era? Infection. 2013;41(2):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kristoffersen US, Lebech AM, Mortensen J, Gerstoft J, Gutte H, Kjaer A. Changes in lung function of HIV-infected patients: a 4,5-year follow-up study. Clinical physiology and functional imaging. 2012;32(4):288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakamura H, Tateyama M, Tasato D, Haranaga S, Ishimine T, Higa F, et al. The prevalence of airway obstruction among Japanese HIV-positive male patients compared with general population; a case-control study of single center analysis. Journal of infection and chemotherapy : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2014;20(6):361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guaraldi G, Besutti G, Scaglioni R, Santoro A, Zona S, Guido L, et al. The burden of image based emphysema and bronchiolitis in HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy. PloS one. 2014;9(10):e109027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leader JK, Crothers K, Huang L, King MA, Morris A, Thompson BW, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Quantitative Evidence of Lung Emphysema and Fibrosis in an HIV-Infected Cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(4):420–427. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Triplette M, Attia EF, Akgun KM, Soo Hoo GW, Freiberg MS, Butt AA, et al. A Low Peripheral Blood CD4/CD8 Ratio Is Associated with Pulmonary Emphysema in HIV. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0170857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pefura-Yone EW, Fodjeu G, Kengne AP, Roche N, Kuaban C. Prevalence and determinants of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in HIV infected patients in an African country with low level of tobacco smoking. Respiratory medicine. 2015;109(2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Onyedum CC, Chukwuka JC, Onwubere BJ, Ulasi II, Onwuekwe IO. Respiratory symptoms and ventilatory function tests in Nigerians with HIV infection. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10(2):130–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nimmo C, Capocci S, Honeyborne I, Brown J, Sewell J, Thurston S, et al. Airway bacteria and respiratory symptoms are common in ambulatory HIV-positive UK adults. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):1208–1211. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00361-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kunisaki KM, Niewoehner DE, Collins G, Nixon DE, Tedaldi E, Akolo C, et al. Pulmonary function in an international sample of HIV-positive, treatment-naive adults with CD4 counts > 500 cells/muL: a substudy of the INSIGHT Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) trial. HIV Med. 2015;16(Suppl 1):119–128. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oelsner EC, Pottinger TD, Burkart KM, Allison M, Buxbaum SG, Hansel NN, et al. Adhesion molecules, endothelin-1 and lung function in seven population-based cohorts. Biomarkers. 2013;18(3):196–203. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.762805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Attia EF, Akgun KM, Wongtrakool C, Goetz MB, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Rimland D, et al. Increased risk of radiographic emphysema in HIV is associated with elevated soluble CD14 and nadir CD4. Chest. 2014;146(6):1543–1553. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lambert AA, Kirk GD, Astemborski J, Mehta SH, Wise RA, Drummond MB. HIV Infection Is Associated With Increased Risk for Acute Exacerbation of COPD. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(1):68–74. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fitzpatrick ME, Gingo MR, Kessinger C, Lucht L, Kleerup E, Greenblatt RM, et al. HIV infection is associated with diffusing capacity impairment in women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(3):284–288. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a9213a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fischer WA, 2nd, Drummond MB, Merlo CA, Thomas DL, Brown R, Mehta SH, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection is not an independent risk factor for obstructive lung disease. Copd. 2014;11(1):10–16. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.800854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Group ISS. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kunisaki KM, Niewoehner DE, Collins G, Aagaard B, Atako NB, Bakowska E, et al. Pulmonary effects of immediate versus deferred antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive individuals: a nested substudy within the multicentre, international, randomised, controlled Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2016;4(12):980–989. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30319-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Serrano-Villar S, Sainz T, Lee SA, Hunt PW, Sinclair E, Shacklett BL, et al. HIV-infected individuals with low CD4/CD8 ratio despite effective antiretroviral therapy exhibit altered T cell subsets, heightened CD8+ T cell activation, and increased risk of non-AIDS morbidity and mortality. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(5):e1004078. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Popescu I, Drummond MB, Gama L, Coon T, Merlo CA, Wise RA, et al. Activation-induced cell death drives profound lung CD4(+) T-cell depletion in HIV-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190(7):744–755. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1226OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aukrust P, Muller F, Svardal AM, Ueland T, Berge RK, Froland SS. Disturbed glutathione metabolism and decreased antioxidant levels in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy–potential immunomodulatory effects of antioxidants. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003;188(2):232–238. doi: 10.1086/376459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kirkham PA, Barnes PJ. Oxidative stress in COPD. Chest. 2013;144(1):266–273. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lassiter C, Fan X, Joshi PC, Jacob BA, Sutliff RL, Jones DP, et al. HIV-1 transgene expression in rats causes oxidant stress and alveolar epithelial barrier dysfunction. AIDS research and therapy. 2009;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pacht ER, Diaz P, Clanton T, Hart J, Gadek JE. Alveolar fluid glutathione decreases in asymptomatic HIV-seropositive subjects over time. Chest. 1997;112(3):785–788. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Diaz PT, Wewers MD, King M, Wade J, Hart J, Clanton TL. Regional differences in emphysema scores and BAL glutathione levels in HIV-infected individuals. Chest. 2004;126(5):1439–1442. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cribbs SK, Guidot DM, Martin GS, Lennox J, Brown LA. Anti-retroviral therapy is associated with decreased alveolar glutathione levels even in healthy HIV-infected individuals. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e88630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Appay V, Almeida JR, Sauce D, Autran B, Papagno L. Accelerated immune senescence and HIV-1 infection. Experimental gerontology. 2007;42(5):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annual review of medicine. 2011;62:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Desai S, Landay A. Early immune senescence in HIV disease. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2010;7(1):4–10. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0038-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cockerham LR, Siliciano JD, Sinclair E, O’Doherty U, Palmer S, Yukl SA, et al. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation are associated with HIV DNA in resting CD4+ T cells. PloS one. 2014;9(10):e110731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hatano H, Jain V, Hunt PW, Lee TH, Sinclair E, Do TD, et al. Cell-based measures of viral persistence are associated with immune activation and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)-expressing CD4+ T cells. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;208(1):50–56. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang W, Lederman MM, Hunt P, Sieg SF, Haley K, Rodriguez B, et al. Plasma levels of bacterial DNA correlate with immune activation and the magnitude of immune restoration in persons with antiretroviral-treated HIV infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2009;199(8):1177–1185. doi: 10.1086/597476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, Epling L, Teague J, Jacobson MA, et al. Valganciclovir reduces T cell activation in HIV-infected individuals with incomplete CD4+ T cell recovery on antiretroviral therapy. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;203(10):1474–1483. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Appay V, Sauce D. Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences. The Journal of pathology. 2008;214(2):231–241. doi: 10.1002/path.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sajadi MM, Pulijala R, Redfield RR, Talwani R. Chronic immune activation and decreased CD4 cell counts associated with hepatitis C infection in HIV-1 natural viral suppressors. AIDS. 2012;26(15):1879–1884. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357f5d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Agusti A, Edwards LD, Rennard SI, MacNee W, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: a novel phenotype. PloS one. 2012;7(5):e37483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gadgil A, Duncan SR. Role of T-lymphocytes and pro-inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2008;3(4):531–541. doi: 10.2147/copd.s1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Armah KA, McGinnis K, Baker J, Gibert C, Butt AA, Bryant KJ, et al. HIV status, burden of comorbid disease, and biomarkers of inflammation, altered coagulation, and monocyte activation. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;55(1):126–136. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]