Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With thirty-six million older adult (OA) US drivers, safety is a critical concern, particularly among those with dementia. It is unclear at what stage of Alzheimer disease (AD) OAs stop driving and whether preclinical AD affects driving cessation.

METHODS

Time to driving cessation was examined based on Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and AD cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers. 1795 OAs, followed up to 24 years received CDR ratings. A subset (591) had CSF biomarker measurements and were followed up to 17 years. Differences in CDR and biomarker groups as predictors of time to driving cessation were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional models.

RESULTS

Higher CDR scores and more abnormal biomarker measurements predicted a shorter time to driving cessation.

DISCUSSION

Higher levels of AD biomarkers, including among individuals with preclinical AD, lead to earlier driving cessation. Negative functional outcomes of preclinical AD show a non-benign phase of the disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, biomarker, driving, driving cessation, older adults, aged, preclinical, cerebrospinal fluid, amyloid beta, tau, ptau

1. Introduction

The decision to stop driving is a difficult one for older adults, their families, and their clinicians. Many older adults are optimistic that they will continue to drive into the foreseeable future.1 However, there is an elevated crash risk and fatality rate for drivers over 65 years.2, 3 Importantly, concerns about driving safety must be balanced with potential negative effects linked to driving cessation. Older adults who stop driving have higher rates of depression, faster decline in overall health, higher rates of admission to long-term care, and higher overall rates of mortality.4–6

It is well known that active dementia is associated with worse driving performance,7–10 and that persons with dementia will eventually need to stop driving altogether. However, little is known about how dementia severity relates to when an older adult needs to cease driving.

In addition, driving difficulties have recently been linked to preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD).11–13 Preclinical AD is signified by abnormal AD biomarkers in the presence of cognitive normality.14, 15 Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) AD biomarkers reflect the accumulation of amyloid and tau lesions and provide a measure of actual underlying pathology.16, 17 In particular, CSF tau/amyloid-β(Aβ)42 and phosphorylated-tau(ptau)181/Aβ42 ratios are believed to be strong predictors of the presence of preclinical AD.16, 17 Cognitively intact older adults with more abnormal biomarker values make more driving errors on a standardized road test and are more likely to have poorer performance on that test longitudinally than those with normal values.11–13 Because AD biomarkers are linked to driving performance, early driving cessation may also be a functional outcome of preclinical AD.

Given the safety and public health implications of driving cessation among older adults, there is an urgent need to better understand the link between driving cessation and the factors that predict it. We examined the time from baseline to driving cessation as a function of AD cerebrospinal fluid biomarker ratios in 591 participants and CDR scores in 1795 participants, over a period of up to 24 years. We hypothesized that individuals with higher baseline CDR scores would stop driving earlier, and that CSF biomarkers would predict time to driving cessation independent of CDR score.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Older adults (age ≥55) were enrolled in studies conducted at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University. Participants, along with a required collateral source, were enrolled in studies without knowledge of whether or not they had abnormal biomarkers. Participants completed an annual clinical assessment, in which experienced clinicians classified participants using the CDR18 based on information from the participant, as well as a collateral source (CS) who knew the participant well and who can discuss intraindividual changes in the participant’s cognition. Collateral sources have been shown to be highly accurate and were individuals who generally interacted with the participant on a daily basis, had known the participant for 30–60 years, and were most often a female (70%) adult child (38%) or a spouse (46%).19

The CDR has well-documented reliability and validity.20–22 A global CDR, which can be used to compare intraindividual change over time, is derived from scores in the areas of memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care.18, 22 Participants were given an annual CDR of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 3, representing cognitively normal, very mild dementia, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia, respectively. During each annual clinical assessment, which lasts approximately ninety minutes, as part of the Initial Subject Protocol,23 the collateral source was asked whether the participant ever drove, whether they drive now, and if so, whether there are problems or risks because of poor thinking. CDR data were available from October 14, 1991 through December 31, 2015.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was acquired after an overnight fast via standard lumbar puncture by experienced neurologists using a 22-gauge Sprotte spinal needle to draw 20–30 mL of CSF.24 CSF analytes (Aβ42, tau, and ptau181; Innotest, Fujirebio [formerly Innogenetics], Ghent, Belgium) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays (ELIZA). CSF samples are gently inverted and centrifuged at low speed to preclude gradient effects. They are then frozen at −84°C after aliquoting into polypropylene tubes. All biomarker assays include a common reference standard, within-plate sample randomization and strict standardized protocol adherence.16 CSF data were available from May 26, 1998 through December 31, 2015.

All research protocols were approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office, and signed informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier curves were used to examine whether individuals with higher baseline CDR scores stop driving earlier compared to those with lower CDR scores. Because only three participants had a CDR ≥ 2, the analyses were restricted to those with baseline CDRs of 0, 0.5, and 1. All analyses were done using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

A Cox proportional hazards model examined the association of baseline CDR with time to driving cessation, while adjusting for, and simultaneously testing the effects of, gender, education, age, race, the presence of an apolipoprotein E ε4 [APOE4] allele, and driving risks because of poor thinking. Except for education and age, all other variables were treated as categorical. Race was categorized as Caucasian and Minority (minority group 96.76% African American). In each model, female gender, Caucasian race and CDR 0 served as the reference categories. Pearson product-moment correlations were used to examine the strength of the associations between model variables to test for multicollinearity. The proportional hazards assumption for each predictor and the Cox shell residuals for overall model fit were examined in the preliminary modeling. A Wald test was used to examine significant differences between individual levels of CDR and APOE4.

The effect of CSF biomarkers on time to driving cessation was then examined. Higher-levels of CSF tau/Aβ42 and ptau181/Aβ42 have been shown as indicative of preclinical AD.15–17 The CSF variables were dichotomized as in our previous work, such that the highest tertile of values was taken to indicate abnormality and was then compared to the lower two tertiles combined.12, 13 The model was repeated twice, once testing the effect of tau/Aβ42 and once testing the effect of ptau181/Aβ42 along with the other variables.

3. Results

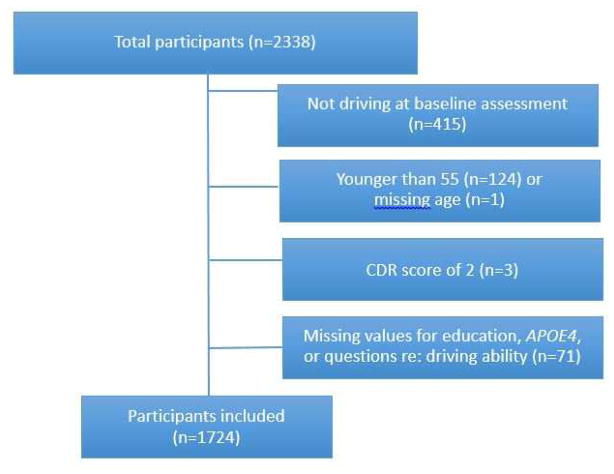

There were 2338 participants in the sample who reported ever driving. Of these, 1923 (82.24%) were still driving at their baseline assessment. After excluding participants younger than 55 years old, participants with a CDR ≥ 2, and participants missing data on any of the demographic variables used in the Cox proportional hazards models, 1724 participants remained (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Participant inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics (N=1724; Biomarker subsample N=559).

| Demographics | (N=1724) | (N=559) |

|---|---|---|

| Women, No. (%) | 894 (51.86) | 300 (53.67) |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 14.72 (3.07) | 15.57 (2.88) |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 72.96 (7.92) | 71.20 (7.27) |

| Minority race,* No. (%) | 185 (10.73) | 45 (8.05) |

| Poor thinking does not affect driving, No. (%) | 1334 (77.38) | 494 (86.51) |

| APOE4+, heterozygous, No. (%) | 639 (37.06) | 196 (36.06) |

| APOE4+, homozygous, No. (%) | 114 (6.61) | 24 (4.29) |

| CDR 0, No. (%) | 914 (53.02) | 404 (72.27) |

| CDR 0.5, No. (%) | 658 (38.17) | 133 (23.79) |

| CDR 1, No. (%) | 152 (8.82) | 22 (3.94) |

| Aβ42, mean (SD), pg/mL | 612.84 (283.75) | |

| tau, mean (SD), pg/mL | 362.14 (223.04) | |

| ptau, mean (SD), pg/mL | 64.33 (33.75) | |

| tau/Aβ42 ratio, mean (SD) | 0.80 (0.82) | |

| ptau/Aβ42 ratio, mean (SD) | 0.14 (0.13) |

Abbreviations: APOE4=apolipoprotein E ε4; CDR=Clinical Dementia Rating

All remaining participants reported their race as Caucasian

3.1. Analyses without biomarkers

Unadjusted analyses

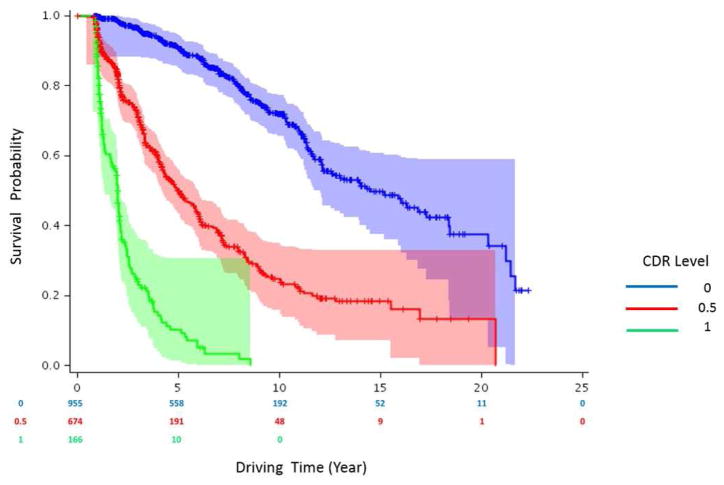

Kaplan-Meier curves for each CDR group were created (Figure 2) and differences between the curves were tested using the log-rank test. Cognitively normal participants (CDR 0) experienced the longest time to driving cessation. Participants with higher baseline CDR scores had a shorter absolute time to driving cessation than those with lower CDR scores. Adjusting for multiple comparisons, there was a statistically significant difference in time to driving cessation between CDR 0 and CDR 0.5 (p<.0001) participants, between CDR 0 and CDR 1 (p<.0001) participants, and between CDR 0.5 and CDR 1 (p=0.005) participants. Median (95% confidence interval [CI]) survival time in years for the groups were 15.2(12.1–18.4), 5.8(4.4–5.8), and 2.0(1.7–2.1) for the CDR 0, 0.5, and 1 groups respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing the relationship between CDR scores and time to driving cessation (N=1724).

Adjusted analyses

In the Cox proportional hazards model, education (Hazards ratio (HR)=1.01; 95% CI=0.98–1.03; p=0.616) and race (HR=0.99; 95% CI=0.75–1.30; p=0.917) had no significant effect on time to driving cessation. Women had a higher risk of driving cessation with time than men (HR=1.26; 95% CI=1.08–1.48; p=0.004). Older age in years was associated with faster time to driving cessation (HR=1.09; 95% CI=1.07–1.10; p<.0001). Examined categorically, when the analysis was repeated dichotomizing the age variable into younger (≤72 years) and older (>72 years) drivers, the older group stopped driving earlier (HR=2.53, 95% CI=2.14–2.99, p<.0001). Having driving problems due to poor thinking (HR=1.32; 95% CI=1.10–1.58; p=0.003), higher baseline CDR level (CDR 0.5 vs. 0: HR=3.84, 95% CI=3.16–4.66; CDR 1 vs. 0: HR=15.07, 95% CI=11.37–19.97; p<.0001), and greater numbers of APOE4 alleles (1 vs.0: HR=1.43, 95% CI=1.20–1.69; 2 vs. 0: HR=1.95, 95% CI=1.46–2.60; p<0.0001) were associated with a faster time to driving cessation.

3.2. Analyses with biomarkers

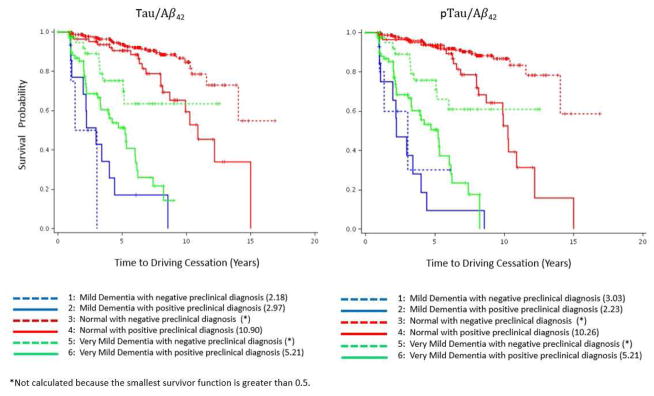

559 of the 1724 participants had CSF data available within six months of an annual clinical assessment date. That clinical assessment date was then considered to be the baseline assessment date in these analyses. Two Cox proportional hazards models were performed for the binary variables of tau/Aβ42 and ptau/Aβ42 separately and each adjusted for the covariates listed previously. In the Cox proportional hazards model testing the effect of tau/Aβ42, only the effect of the biomarker ratio (HR=2.04; 95% CI=1.28–3.22; p<0.003), age (HR=1.08; 95% CI=1.04–1.11; p<.0001), and CDR (CDR 0.5 vs. 0: HR=3.44, 95% CI=2.10–5.63; CDR 1 vs. 0: HR=5.80, 95% CI=2.59–12.99; p<0.001) had a significant effect on driving cessation. Similar results were found in the model that tested the effects of ptau/Aβ42, where the biomarker ratio (HR=2.48; 95% CI=1.59–3.86; p<0.001), age (HR=1.08; 95% CI=1.04–1.11; p<.0001) and CDR (CDR 0.5 vs. 0: HR=3.50, 95% CI=2.16–5.66; CDR 1 vs. 0: HR=5.56, 95% CI=2.45–12.60; p<0.001) were found to be significant. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each combination of biomarker status (positive or negative) and CDR score (0, 0.5, or 1) for tau/Aβ42 and ptau/Aβ42.

4. Discussion

This study sought to determine time to driving cessation as a function of dementia severity and CSF biomarker levels in a group of actively-driving, cognitively normal and mildly impaired older adults. We found that participants with very mild dementia (CDR 0.5) stopped driving at approximately three and a half times the rate per year as those who were CDR 0 at baseline. For those with mild dementia (CDR 1), cessation was over five times the rate per year compared to CDR 0. Additionally, we found that those with abnormal CSF biomarkers levels stopped driving at approximately twice the rate per year compared to those with normal CSF levels.

Although it is logical that those with a higher baseline CDR score would stop driving sooner, prior large studies examining cognitive impairment severity and driving cessation were either cross-sectional25–27 or brief (five years or shorter).10, 28 One large study assessed cessation and cognition over a 10 year period.29 To our knowledge, there are no large studies that have examined driving cessation over a longer time period, nor have others examined relationships between AD biomarkers and driving cessation.

Drivers who were older or APOE4 positive stopped driving earlier. However, the effect of APOE4 was no longer significant when our model included biomarkers. Past research has shown that individuals who are APOE4 positive have more abnormal Aβ42.30 Therefore, APOE4 may have been significant in our earlier analyses because of its relationship to Aβ42 levels.

Somewhat surprisingly, education and race did not appear to play a role in time to driving cessation. Multiple studies have found that those who stopped driving were more likely to be non-white and less educated.31–34 Our results suggest that other factors may drive these differences rather than simply education or race.

Interestingly, while gender did influence the timing of driving cessation in our first model, this effect was no longer significant when AD biomarker levels were added. Prior work has suggested that older adult women stop driving earlier than older adult men, both when cognitively normal and when affected by dementia.35 Even before they are experiencing dementia symptoms, women have been found to restrict their driving more often in the years leading up to a dementing illness.36 However, our analyses suggest that gender differences in driving cessation may be an artifact of differences in underlying pathology levels between our gender groups.

The current study has some limitations including a fairly homogeneous sample of research participants. The study participants are generally well-educated, with minority representation slightly lower than the greater St. Louis region. Furthermore, we do not have information on whether a doctor or family member forced cessation, and this would be a useful area of further study. Additionally, while the CDR score and biomarker levels are significant predictors of driving cessation, these tests are not currently available at all clinics and CSF biomarker collection is rarely covered by insurance. The use of biomarkers is nonetheless potentially useful in future designs of longitudinal, observational, and intervention studies of AD and driving.

In 2011, Sperling, et al suggest that determining very early functional changes could illuminate the conversion from pathologic, preclinical AD to the clinical symptoms of AD.37 Recently, studies of preclinical AD have found that changes in sensory and motor functioning may occur before cognitive symptoms.38 These include decline in visuomotor abilities among many individuals with preclinical AD,39 as well as spatial navigational abilities.40 It is likely that all of these subtle changes in physical and sensory domains combine to impact the complex skill of driving and influence driving cessation.13 Future studies should examine this theory in greater detail, including looking further at sensorimotor deficits and information processing.

Our results suggest that AD biomarker levels are associated with driving cessation in older adults, even in the preclinical stage of the disease. The safety of older drivers is an important public health concern. Driving cessation continues to be a worrisome topic among older adults with early dementia and caregivers who share concerns about the risk of future cognitive decline. Most physicians believe that early dementia should not universally be prohibitive of driving;41 however, this finding could alert physicians to a need for continued monitoring. With better understanding of the outlook, future work should look at interventions targeted at those most at risk of unsafe driving and driving cessation, thus allowing for both continued autonomy and increased safety for individuals and communities.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the relationships between biomarker levels and Clinical Dementia Rating combinations, and time to driving cessation for (A) tau/Aβ42 and (B) ptau/Aβ42 (N=559). Numbers in the legend indicate median survival time in years for each group.

*Not calculated because the smallest survivor function is greater than 0.5.

Research in context.

1. Systematic review

In the review of literature, the authors found driving cessation work was mainly cross-sectional or involved a small participant pool. The authors found no study examining whether driving cessation is associated with Alzheimer disease (AD) biomarkers.

2. Interpretation

AD biomarkers and Clinical Dementia Ratings predict time to driving cessation, indicating that preclinical AD is not without functional consequences.

3. Future directions

Future work should include longitudinal examination of driving in older adults, with the inclusion of AD biomarker information. Driving performance is also a possible functional outcome in primary and secondary AD prevention trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging [R01 AG056466, R01AG043434, R01AG43434-03S1, P50AG005681, P01AG003991, and P01AG026276]; Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan, the Farrell Family Research Fund, and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors thank the participants, investigators, and staff of the Knight ADRC Clinical Core for participant assessments, Genetics Core for APOE genotyping, and Biomarker Core for cerebrospinal fluid analysis. The authors gratefully acknowledge the expertise and suggestions offered by Dr. Brian Ott of Brown University for the submission of this manuscript. Sarah H. Stout had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Ms. Stout contributed to conception and design of the study; collection, management, and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the final manuscript,.

Dr. Babulal contributed to conception and design of the study; analysis and interpretation of the data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Mr. Ma contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Carr contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Head contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Grant contributed to analysis, and interpretation of the data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Williams contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Holtzman contributed to collection and interpretation of the data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Fagan contributed to conception and design of the study; collection, management, and interpretation of the data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Morris contributed to conception and design of the study; interpretation of the data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Roe contributed to conception and design of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation of the final manuscript, supervision, and obtaining funding.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Ms. Stout reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Babulal reports no conflicts of interest.

Mr. Ma reports no conflicts of interest

Dr. Carr receives support from NIA (R01 AG043434; Roe-PI and K23; Betz-PI), NEI (R01 EY026199-01; Bhorade-PI), Missouri Department of Transportation (16-M2PE-05-002; Carr-PI, 16-DL-02-002; Carr-PI and 16-DL-02-003; Barco-PI), State Farm Insurance (Carr-PI), and HealthSouth (Carr-PI) and has past Consulting Relationships in the last two years with The Traffic Injury Research Foundation, Medscape, the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety and the American Geriatric Society. Dr. Carr reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Head reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Grant reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Williams reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Holtzman receives funding from C2N Diagnostics SAB, Genentech SAB, and Neurophage SAB. He is a consultant for AbbVie. His lab receives grants from the NIH, the JPB Foundation, Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, the Tau Consortium, Eli Lilly, and C2N Diagnostics. Dr. Holtzman reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Fagan is on the scientific advisory boards of IBL International and Roche and is a consultant for AbbVie, Novartis and DiamiR. Dr. Fagan reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Morris and his family do not own stock or have equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Morris has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by the following companies: Janssen Immunotherapy, Pfizer, Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, SNIFF (The Study of Nasal Insulin to Fight Forgetfullness) study, and A4 (The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease) trial. Dr. Morris has served as a consultant for Lilly USA, and Charles Dana Foundation. He receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants # P50AG005681; P01AG003991; P01AG026276 and UF1AG032438. Dr. Morris reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Roe reports no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ross LA, Dodson JE, Edwards JD, Ackerman ML, Ball K. Self-rated driving and driving safety in older adults. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2012;48:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boot WR, Stothart C, Charness N. Improving the safety of aging road users: A mini-review. Gerontology. 2013;60:90–96. doi: 10.1159/000354212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayhew DR, Simpson HM, Ferguson SA. Collisions involving senior drivers: High-risk conditions and locations. Traffic injury prevention. 2006;7:117–124. doi: 10.1080/15389580600636724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liddle J, Turpin M, Carlson G, McKenna K. The needs and experiences related to driving cessation for older people. Br J Occup Ther. 2008;71:379–388. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liddle J, Bennett S, Allen S, Lie DC, Standen B, Pachana NA. The stages of driving cessation for people with dementia: needs and challenges. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:2033–2046. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor BD, Tripodes S. The effects of driving cessation on the elderly with dementia and their caregivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2001;33:519–528. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iverson DJ, Gronseth GS, Reger MA, Classen S, Dubinsky RM, Rizzo M. Practice parameter update: Evaluation and management of driving risk in dementia: Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology. 2010;74:1316–1324. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181da3b0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hird MA, Egeto P, Fischer CE, Naglie G, Schweizer TA, Pachana N. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of On-Road Simulator and Cognitive Driving Assessment in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;53:713–729. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett JM, Chekaluk E, Batchelor J. Cognitive Tests and Determining Fitness to Drive in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64:1904–1917. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anstey KJ, Windsor TD, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. Predicting Driving Cessation over 5 Years in Older Adults: Psychological Well-Being and Cognitive Competence Are Stronger Predictors than Physical Health. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott BR, Jones RN, Noto RB, et al. Brain amyloid in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease is associated with increased driving risk. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring. 2017;6:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roe CM, Barco PP, Head DM, et al. Amyloid Imaging, Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers Predict Driving Performance Among Cognitively Normal Individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31:69–72. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roe CM, Babulal GM, Head DM, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and longitudinal driving decline. Alzheimer’s & dementia (New York, N Y) 2017;3:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunderland T, Linker G, Mirza N, et al. Decreased β-Amyloid1–42 and Increased Tau Levels in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Alzheimer Disease. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:2094–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blennow K, Dubois B, Fagan AM, Lewczuk P, De Leon MJ, Hampel H. Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2015;11:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid(42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:343–349. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.noc60123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Racine AM, Koscik RL, Nicholas CR, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid ratios with Aβ42 predict preclinical brain β-amyloid accumulation. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring. 2016;2:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cacchione PZ, Powlishta KK, Grant EA, Buckles VD, Morris JC. Accuracy of collateral source reports in very mild to mild dementia of the alzheimer type. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:819–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams MM, Roe CM, Morris JC. Stability of the clinical dementia rating, 1979–2007. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:773–777. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC, McKeel DW, Jr, Fulling K, Torack RM, Berg L. Validation of clinical diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:17–22. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke WJ, Miller JP, Rubin EH, et al. Reliability of the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:31–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520250037015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis PB, Morris JC, Grant E. Brief screening tests versus clinical staging in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roe CM, Fagan AM, Grant EA, et al. Amyloid imaging and CSF biomarkers in predicting cognitive impairment up to 7. 5 years later. Neurology. 2013;80:1784–1791. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918ca6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada H, Tsutsumimoto K, Lee S, et al. Driving continuity in cognitively impaired older drivers. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2016;16:508–514. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lafont S, Laumon B, Helmer C, Dartigues J-F, Fabrigoule C. Driving cessation and self-reported car crashes in older drivers: the impact of cognitive impairment and dementia in a population-based study. Journal Of Geriatric Psychiatry And Neurology. 2008;21:171–182. doi: 10.1177/0891988708316861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wackerbarth S, Johnson MMS. Predictors of driving cessation, independent living and power of attorney decisions by dementia patients and caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 1999;14:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards JD, Ross LA, Ackerman ML, et al. Longitudinal predictors of driving cessation among older adults from the ACTIVE clinical trial. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:P6–P12. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.1.p6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi M, Lohman MC, Mezuk B. Trajectories of cognitive decline by driving mobility: evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29:447–453. doi: 10.1002/gps.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Annals of Neurology. 2010;67:122–131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dugan E, Lee CM. Biopsychosocial risk factors for driving cessation findings from the health and retirement study. Journal of aging and health. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0898264313503493. 0898264313503493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi M, Mezuk B, Lohman MC, Edwards JD, Rebok GW. Gender and racial disparities in driving cessation among older adults. Journal of aging and health. 2013;25:147S–162S. doi: 10.1177/0898264313519886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waldorf B. Automobile reliance among the elderly: Race and spatial context effects. Growth and Change. 2003;34:175–201. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann WC, McCarthy DP, Wu SS, Tomita M. Relationship of health status, functional status, and psychosocial status to driving among elderly with disabilities. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2005;23:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Wahlström B. Why do older drivers give up driving? Accident Analysis and Prevention. 1998;30:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dit Asse LM, Fabrigoule C, Helmer C, Laumon B, Lafont S. Automobile driving in older adults: Factors affecting driving restriction in men and women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62:2071–2078. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albers MW, Gilmore GC, Kaye J, et al. At the interface of sensory and motor dysfunctions and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2015;11:70–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mollica MA, Navarra J, Fernández-Prieto I, et al. Subtle visuomotor difficulties in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuropsychology. 2017;11:56–73. doi: 10.1111/jnp.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allison SL, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Head D. Spatial Navigation in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;52:77–90. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkinson MA, Berg-Weger ML, Carr DB, et al. Driving and dementia of the Alzheimer type: Beliefs and cessation strategies among stakeholders. Gerontologist. 2005;45:676–685. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]