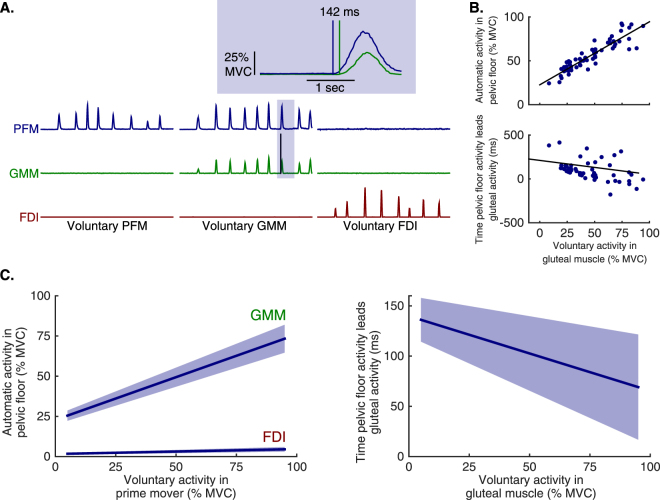

Figure 1.

Electromyographic (EMG) evidence of two muscle coordination patterns involving human pelvic floor muscles (PFM) that the brain can voluntarily access. (A) Example EMG recordings from the PFM (blue), gluteus maximus muscle (GMM, green), and the first dorsal interosseous muscle (FDI, red) in a single participant during repeated and separate voluntary activations of the PFM, GMM, and FDI. Voluntary activation of the PFM elicits the isolated-pelvic coordination pattern which does not have co-activation of the GMM or FDI. Voluntary activation of the GMM activates the gluteal-pelvic coordination pattern which co-activates the GMM and PFM. The inset shows one example voluntary GMM activation, demonstrating that coordinated PFM activity occurred in advance of GMM activity. (B) Example of EMG amplitude and latency in a single participant as voluntary GMM activation is increased. Since all participants performed repeated and scaled muscle contractions, each participant provided EMG data that were used in the group analyses. (C) left. Population average (solid line, ± SEM) PFM activation – separately during voluntary GMM activation and voluntary FDI activation – from a linear mixed model with participant-level random intercepts and slopes. Increases in PFM activation associated with increases in voluntary GMM activation were significantly larger than those associated with increases in voluntary FDI activation (p < 0.005). (C) right. Population average (solid line, ± SEM) PFM activation latency relative to the onset of the GMM – during voluntary GMM activation – from a linear mixed model with participant-level random intercepts and slopes. PFM activation led GMM activation across the range of voluntary GMM activation, with slightly shorter latencies for higher levels of voluntary GMM activation (p = 0.03).