Abstract

Evaluating the feeding value of wet okara as a protein supplement for lactating ewes with twin lambs was the objective. A 4 × 4 Latin square replicated 2× (4 sheep, 4 treatments, 4 periods per square; 2 squares) was conducted to examine the influence of concentrate mix (okara or not) and type of forage (silage or hay) on ewe milk composition and growth of their lactating lambs. Treatment periods were 14 days (7 days adaptation and 7 days collection). Ewes (55 to 74.8 kg BW) were fed 1 of 4 diets: wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay (TSH), okara and corn with mixed grass hay (OSH), soybean and wheat middlings with hay crop silage (TSS), and okara and corn with hay crop silage (OSS). Ewes fed hay diets had lower forage dry matter intakes than ewes fed silage. Intake of okara supplement was higher (P < 0.05) with OSH (3.64 kg/d) than with OSS (1.70 kg/d). There was no difference in supplement intake between TSH and TSS. There were no differences among diets for lamb daily gains or in ewe milk compositions among the diets. Okara is an effective source of protein for lactating ewes and their twin lambs.

Keywords: Okara, Protein, Lactating ewe, Suckling lamb

1. Introduction

Competition between food for rising human populations and feed for animals is pushing up the cost of livestock production, increasing the need to look for by-product feeds from food and drink manufacturing. One such waste product is okara, the residue from the production of soymilk and tofu. Okara is an off-white pulp that consists of the insoluble parts of soybeans and contains approximately 20% dry matter. On a dry matter basis (DM), okara contains 25% to 29% crude protein (% of DM), 75% total digestible nutrients (% of DM), and 30% neutral detergent fiber (% of DM) (O'Toole, 1999). While okara is consumable by humans, production of okara exceeds the demand for human consumption. Consumption of okara by humans is further confounded by the high fiber content of okara, which makes it much less able to be consumed in mass quantities by humans. Okara is used as animal feed (Wlek and Zollitsch, 2004, Sinha et al., 2013), but in some areas it is also burnt as fuel or even dumped in landfills (O'Toole, 1999).

For farmers raising meat sheep, one of the most important factors in maintaining economic viability is how quickly and efficiently their lambs grow. High growth rate and efficiency decrease the time that it takes the lambs to reach market weight, which in turn decreases the labor and feed costs associated with raising lambs. There have recently been a number of studies evaluating okara as a protein feed for growing ruminants (Rahman et al., 2014; Harjanti et al., 2012), but little is known about the effect of okara on lactating ruminants. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the effect of okara as a protein supplement on ewe feed intake, milk composition, and lamb growth.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and housing

Eight Dorset ewes and their twin lambs from the indoors. Ewes were in their second or later lactation, and were in early lactation and weighed between 55.6 and 74.8 kg. At the start of the study lambs had a mean body weight of 9.39 kg (ranging between 6.96 and 12.11 kg) and were between 9 and 16 days old.

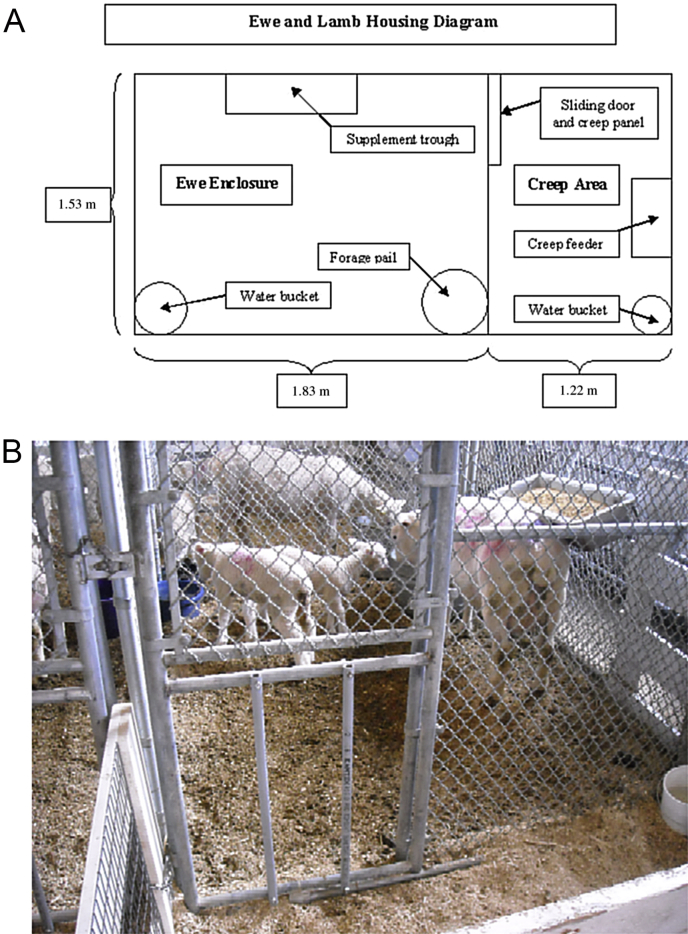

Ewes were housed individually with their own lambs in 8 separate pens measuring 1.53 m × 1.83 m with an attached creep area measuring 1.22 m × 1.53 m (Fig. 1A). The creep area and ewe enclosure were connected by a sliding door that served as the creep panel and access to the pen. Water buckets were located in a back corner of the pen, concentrate feeders were hung on the chain link walls of the pen and the forage pail was located in a front corner of the pen. In the creep area, water buckets were located in a front corner and the creep feed trough was hung on the front or side of the fence panels. Concentrate feeders were hung at the top of the pen such that ewes could access the concentrate, but lambs could not. Forage pails were at floor level, but lambs did not express an interest in the forages during the course of the study (Fig. 1B). Sawdust was used as the bedding material.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of housing (A) and photo of ewe and lamb housing (B).

2.2. Experimental design, sample collection, and analysis

The replicated Latin square study was divided into 4 periods, each period having a 7-day adjustment time and 7 days of data collection. Feed intake data was collected on a daily basis and samples of 10 g were taken out of each ewe's refusals each day. Each day's 10 g refusal samples were stored and analyzed at the end of each period. Samples of the feed offered were also analyzed to determine the actual nutrient composition of the feed consumed. Creep feed intake was also recorded on a daily basis. Ewe and lamb weights were recorded once a week using a Tru-Test AG350 Indicator animal scale (Tru-Test Distributors Limited, Pakuranga, New Zealand) for ewes and lambs weighing over 10 kg and using a OHAUS ES Series data ranger scale (Ohaus Corp., Pine Brook, NJ) for lambs weighing less than 10 kg. Milk samples were also taken once a week, stripping the teats before taking each sample. Lambs were not separated from ewes except during the milk collection period. Milk samples were analyzed for percent fat, true protein, lactose and total solids using Milkoscan/Fossomatic equipment. The Milkoscan use Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) technology for the determination of milk components. Feed samples were tested for dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), net energy for lactation (NEL), acid detergent fiber (ADF), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), total digestible nutrients (TDN), lignin, Ca and P using near infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIR).

2.3. Diets

Ewes were randomly assigned to 4 dietary treatments (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3): a wheat middling and corn concentrate fed with a mixed grass hay (TSH), an okara and corn concentrate fed with mixed grass hay (OSH), a soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate fed with hay crop silage (TSS), and an okara and corn concentrate fed with hay crop silage (OSS). Diets were formulated with the Small Ruminant Nutrition System (Tedeschi et al., 2008) for a 50-kg lactating ewe producing 1.5 kg of milk a day at 6.5% milk fat and 5.2% true protein. Daily dry matter intake was estimated to be about 3 kg. Diets were formulated to satisfy the National Resource Council (NRC, 2007) recommendations. Dietary treatments were rotated every 14 days. Ewes were offered forage and concentrate daily at 08:00, using the previous day's intake to estimate intake and to allow for 10% refusals. Forages and concentrate were offered in separate feeders. Additional feed was added in the evening at about 17:30 as needed. Water was offered ad libitum. Creep feed was offered to lambs at the beginning of each week, with extra added as necessary during the week to allow for ad libitum intake. Okara was obtained locally and stored in a cooler at −1 to 4.4 °C, as were the okara mixed diets. Enough silage for the week was collected from a bunker silo and also stored in the cooler. Diets were designed to be iso-nitrogenous. However, this did not occur, as our pre-experimental hay was higher quality than what was actually fed to the ewes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Concentrate compositions (g/kg DM fed).

| Item | TSH1 | OSH2 | TSS3 | OSS4 | Creep5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean meal | – | – | 222 | – | 248 |

| Wheat middlings | 308 | – | 517 | – | – |

| Corn (ground) | 500 | – | – | – | – |

| Corn (cracked) | – | 415 | – | 109 | 431 |

| Okara | – | 545 | – | 860 | – |

| Soy hulls | – | – | – | – | 230 |

| Molasses | 148 | – | 178 | – | – |

| Ammonium chloride | 16 | 10 | 19 | 7 | |

| Vitamin–mineral premix | 27 | 15 | 33 | 12 | 10 |

| Calcium carbonate | – | 15 | 33 | 12 | 8 |

| CSF vitamin E premix6 | – | – | – | – | 2.5 |

| Decox, 6% concentrate | – | – | – | – | 0.5 |

| Water | – | – | – | – | 70 |

CSF = Cornell sheep flock.

A wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

An okara and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

A soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate with hay crop silage.

An okara and corn concentrate with hay crop silage.

For lamb consumption only.

Premix contained 19,075 mg/kg (DM basis) and 17,011 mg/kg (air dry basis) of vitamin E.

Table 2.

Nutrient composition (g/kg DM) of forages used for diets as analyzed.1

| Item | TSH2 | OSH3 | TSS4 | OSS5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | 916 | 907 | 386 | 380 |

| CP | 132 | 135 | 185 | 194 |

| NEL, Mcal/kg | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.13 | 1.17 |

| ADF | 415 | 456 | 400 | 406 |

| NDF | 655 | 636 | 518 | 510 |

| TDN | 549 | 508 | 529 | 536 |

| Lignin | 72.8 | 89.3 | 72.9 | 90.0 |

| Ca | 8.1 | 9.2 | 13.5 | 13.1 |

| P | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

DM = dry matter; CP = crude protein; NEL = net energy for lactation for dairy cattle; ADF = acid detergent fiber; NDF = neutral detergent fiber; TDN = total digestible nutrients.

Values were determined by NIR (Dairy One, Ithaca, NY, USA).

A wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

An okara and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

A soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate with hay crop silage.

An okara and corn concentrate with hay crop silage.

Table 3.

Nutrient composition of concentrate supplements.1

| Item | TSH2 | OSH3 | TSS4 | OSS5 | Creep feed6 | Okara |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM, g/kg DM | 855 | 232 | 885 | 255 | 895 | 223 |

| CP, g/kg DM | 245 | 291 | 261 | 294 | 210 | 391 |

| NEL, Mcal/kg DM | 1.92 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 1.94 | 2.387 | 2.05 |

| ADF, g/kg DM | 104 | 98 | 109 | 107 | – | 201 |

| NDF, g/kg DM | 176 | 202 | 180 | 159 | 247 | 319 |

| TDN, % DM | 810 | 804 | 810 | 822 | – | 770 |

| Ca, % DM | 4.0 | 16.2 | 13.2 | 17.9 | 5.8 | 2.3 |

| P, % DM | 5.4 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

DM = dry matter; CP = crude protein; NEL = net energy for lactation; ADF = acid detergent fiber; NDF = neutral detergent fiber; TDN = total digestible nutrients.

Values were determined by NIR (Dairy One, Ithaca, NY, USA).

A wheat middling and corn concentrate fed with mixed grass hay.

An okara and corn concentrate fed with mixed grass hay.

A soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate fed with hay crop silage.

An okara and corn concentrate fed with hay crop silage.

Creep feed values based on calculations, not feed analysis; only consumed by lambs.

This value is metabolizable energy per kilogram.

2.4. Statistical design and welfare assurance

Data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis models in the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS, version 7.0 software (SAS, 1998) according to Templeman and Douglass (1999). Statistical design was a replicated 4 × 4 Latin square (Table 4). In Latin Squares the treatments are grouped in 2 different ways. Every row and every column has every treatment and every sheep has every diet. The effect of the grouping is to eliminate from the errors all differences among sheep and treatments (Cochran and Cox, 1992). Because of the Latin square design, no interactions could be obtained without confounding with period. Class variables were period, diet and sheep, and the covariance structure was assumed to be first order autoregressive. Degrees of freedom were calculated using the Satterthwaite method. Sheep and diet were random, period is fixed. As noted above, there was a 7-day adjustment per period followed by a 7-day collection for each sheep. Treatments consisted of 2 types of concentrate and 2 types of forage for 4 treatments. Differences among diets were determined using Tukey's test for all treatment comparisons. Significance was P < 0.05 unless otherwise stated. The study had Institutional Care and Committee Use approval, ensuring that all current standard operating practices for the health and welfare of the sheep were followed.

Table 4.

Representation of design used in study.1

| Sheep | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replication 1 | ||||

| 1 | TSH | OSH | TSS | OSS |

| 2 | OSH | TSS | OSS | TSH |

| 3 | TSS | OSS | TSH | OSH |

| 4 | OSS | TSH | OSH | TSS |

| Replication 2 | ||||

| 5 | TSH | OSH | TSS | OSS |

| 6 | OSH | TSS | OSS | TSH |

| 7 | TSS | OSS | TSH | OSH |

| 8 | OSS | TSH | OSH | TSS |

TSH is a wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay; OSH is an okara and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay; TSS is a soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate with hay crop silage; OSS is an okara and corn concentrate with hay crop silage. Replications 1 and 2 were conducted simultaneously, and sheep included ewe and her lambs.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Ewe diet intakes and composition

Because milk supplies the majority of the nutrients needed by suckling lambs, composition and quantity are important to suckling lamb growth (Hegarty et al., 2006). If the ewe diet can be manipulated to increase the quantity or nutritive properties of the milk, growth rates of the suckling lambs should also increase. Suckling lambs grow to heavier weights before weaning, thus having to spend less time on farm consuming feed that could be used to feed pregnant and lactating ewes. Manipulating lactating ewe diets to increase the volume of nutrients produced in the milk without increasing the cost of feeding those lactating ewes, the profit margin would increase. No difference was seen in the lamb mean daily gains and mean rate of gain at P > 0.05 (96 g/d), suggesting diets did not influence amount of nutrients lambs were receiving. Each diet was equally effective at producing growth in lambs and maintaining plane of nutrition in the lactating ewes. Shuhong et al. (2013) reported in a review of literature that okara crude protein content ranged from 160 to 334 g/kg with the majority of research reporting crude protein in the range of 240 to 300 g/kg. While this is lower than the average soybean meal in the USA (480 g/kg), this would not account for results observed in our study, as our study balanced diet composition.

Ewe mean daily dry matter intake was not significant between periods or between diets, but there were differences between the daily dry matter intakes of supplement and of forages (P < 0.05; Table 5). The amount of okara supplement consumed by ewes fed hay tended to be larger than the amount of okara supplement consumed by ewes fed hay crop silage (P = 0.07). The lower intake of the okara-based supplement for the ewes fed hay crop silage as forage could possibly be accounted for by the high NDF content of the supplement, which contained less corn than the okara-based supplement for the ewes fed grass hay (Table 3). There was also a difference between the dry matter intakes of forages: there was significantly higher intake of hay crop silage than of hay (P ≤ 0.05), but there was no difference in the intake of hay crop silage between diets TSS and OSS or of hay between diets TSH and OSH (P > 0.05). Silage had lower NDF than hay. Rahman et al. (2014) in an okara study on the growth performance of goats fed okara waste also saw no difference in performance when diets were balanced for composition.

Table 5.

Mean daily dry matter intake (kg/d).

| Item | TSH1 | OSH2 | TSS3 | OSS4 | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage | 0.62a | 0.61a | 1.65b | 1.59b | 0.180 |

| Supplement | 2.88ab | 3.64b | 2.57ab | 1.70a | 0.470 |

| Total intake by ewe | 3.50 | 4.25 | 4.21 | 3.29 | 0.392 |

| Creep feed5 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.060 |

| Total intake6 | 3.97 | 4.67 | 4.66 | 3.64 | 0.416 |

SE = standard error.

a,b Means within a row followed by the same letter were not different (P > 0.05).

A wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

An okara and corn concentrate fed with mixed grass hay.

A soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate fed with hay crop silage.

An okara and corn concentrate fed with hay crop silage.

Consumed only by lambs.

By lamb and ewe.

3.2. Milk composition

While there was not a significant difference between milk fat percentage among the 4 diets (P > 0.05), there was a trend towards higher milk fat percentage in diets with hay crop silage fed as the forage versus diets with grass hay (Table 6). Silage diets resulted in greater forage intake than hay diets and tended towards lower concentrate intake. Higher intake of the silage tended to result in increased NDF intake (Table 7). Higher NDF intake would lead to more acetate precursors, which leads to more milk fat. Percentage of protein in milk did not follow this trend and was also not significantly different among the 4 diets. Milk protein content was shown in one study not to be affected by crude protein concentration in the feed consumed by ewes (Roy et al., 1999). There was not a significant difference in milk urea nitrogen (MUN) concentration among the different diets (P > 0.05), but there was a trend for diets with grass hay as the forage to have higher MUN. This was especially true for the MUN concentration of Diet OSH, which had the higher supplement intake. There was no difference in the concentration of lactose in the milk among the different diets (P > 0.05), which was expected because lactose acts as the main osmotic regulator in milk production. The difference in total solids among diets was not statistically significant (P > 0.05), though there was a trend toward higher solids in the diets fed hay crop silage. This can be explained by the trend towards higher milk fat percentages in the diets fed hay crop silage as the forage.

Table 6.

Ewe milk composition (% of milk) as influenced by diet.

| Item | TSH1 | OSH2 | TSS3 | OSS4 | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | 6.02 | 6.10 | 6.85 | 7.20 | 0.516 |

| Total protein | 4.64 | 4.81 | 4.5 | 4.64 | 0.165 |

| MUN, mg/dL | 8.14 | 12.76 | 6.87 | 7.41 | 1.7 |

| Lactose | 4.98 | 4.92 | 5.12 | 5.00 | 0.493 |

| Total solids | 16.46 | 16.82 | 17.55 | 17.94 | 0.060 |

SE = standard error; MUN = milk urea nitrogen.

A wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

An okara and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

A soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate with hay crop silage.

An okara and corn concentrate with hay crop silage.

Table 7.

Daily intake (kg/d) of nutrients per day.

| Item | TSH1 | OSH2 | TSS3 | OSS4 | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEL, Mcal/d | 6.16 | 7.51 | 6.62 | 5.16 | 0.41 |

| TDN | 2.64 | 3.24 | 2.95 | 2.24 | 0.34 |

| NDF | 0.99 | 1.12 | 1.34 | 1.08 | 0.21 |

| CP | 0.78 | 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.81 | 0.26 |

SE = standard error; NEL = Net energy for lactation; TDN = total digestible nutrients; NDF = nutrient detergent fiber; CP = crude protein.

A wheat middling and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

An okara and corn concentrate with mixed grass hay.

A soybean meal and wheat middling concentrate with hay crop silage.

An okara and corn concentrate with hay crop silage.

4. Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to determine whether okara was an effective protein source for lactating ewes. Using okara as a protein supplement would be beneficial to farmers and tofu or soymilk producers because it would provide an inexpensive source of protein for animal consumption and also eliminate the disposal problems faced by tofu and soymilk producers. Thus, there is a definite possibility that a mutually beneficial relationship could be formed between farmers and tofu and soymilk producers.

There is still much research to be done to further investigate okara as a livestock protein supplement. In the 20% dry matter form, okara can be difficult to handle, which poses a problem for many livestock producers. Investigating the drying of okara for use as an animal feed would be beneficial. It would also be interesting to look further into the fermentation of 20% dry matter okara and its effects on rumen digestibility. Future research could also examine whether okara is equally effective as a feed for growing weaned lambs as it is for lactating ewes.

Acknowledgment

An honors thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Animal Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a bachelor's degree with distinction in research by the senior author.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Cochran W.G., Cox G.M. 2nd ed. Wiley; NY: 1992. Experimental designs. [Google Scholar]

- Harjanti D.W., Sugawara Y., Al-Mamun M., Sano H. Effects of replacing concentrate with soybean curd residue silage on ruminal characteristics, plasma leucine, and glucose turnover rates in sheep. J Anim Sci Adv. 2012;2(4):361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty R.S., Warner R.D., Patrick D.W. Genetic and nutritional regulation of lamb growth and muscle characteristics. Aust J Agric Res. 2006;57:721–730. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC) The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2007. Nutrient requirements of small ruminants: sheep, goats, cervids, and new world camelids. [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole D.K. Characteristics and use of okara, the soybean residue from soy milk production – a review. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:363–371. doi: 10.1021/jf980754l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.M., Nakawaga T., Abdullah R.B., Emong W.K.W., Akashi R. Feed intake and growth performance of goats supplemented with soy waste. Pesq Agropec Bras. 2014;49(7):448–554. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., Laforest J.P., Castonguay F., Brisson G.J. Effects of maturity of silage and protein content of concentrates on milk production of ewes rearing twin or triplet lambs. Can J Anim Sci. 1999;79:499–508. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 1998. The SAS system, version 7.0. [Google Scholar]

- Shuhong L., Zhu L., Li K., Yang Y., Lei Z., Zhang Z. Soybean curd residue: composition, utilization, and related limiting factors. Ind Eng. 2013;2013 Article ID 423590, 8 pages. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S.K., Sinha A.K., Mahto D.K., Ranjan R. Study on the growth performance of the broiler after feeding of okara meal containing with or without non-starch polysaccharides degrading enzyme. Vet World. 2013;36(6):325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi L.O., Cannas A., Fox D.G. A nutrition mathematical model to account for dietary supply and requirements of energy and nutrients for domesticated small ruminants: the development and evaluation of the small ruminant nutrition system. Rev Bras Zootec. 2008;37(suplemento especial):178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Templeman R.J., Douglass L.W. ASAS national meetings, July 23. 1999. NCR-170 ASAS mixed model workshop. [Google Scholar]

- Wlek S., Zollitsch W. Sustainable pig nutrition in organic farming: by-products from food processing as a resource. Renew Agric Food Syst. 2004;19(3):159–167. [Google Scholar]