Abstract

Objective

In October 2004, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) directed pharmaceutical companies to issue box warnings about the potential link between the use of antidepressants and suicidal ideation among children. The objective of this paper is to analyze the long-run trends in antidepressant use among children before and after the box warning for those with and without severe psychological impairment.

Methods

The analysis uses data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) for children aged 5–17, covering years 2000–2011. The paper compares the changes in the rate of any antidepressant use in the early post-warning years (2004–07) and late post-warning years (2008–2011) to the pre-warning years (2002–03) using multivariate probit models. Recycled predictions methods are used to estimate yearly predicted probabilities of use.

Results

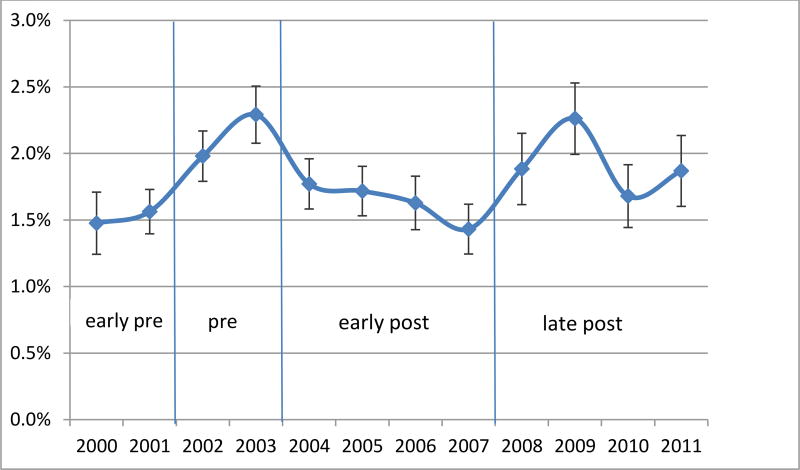

There was a .5% statistically significant decline in the probability of using any antidepressants during the early post-warning years (2004–07) compared to pre-warning years adjusting for all covariates. In the long-run (2008–11), however, there was no statistically significant difference. Five years after the warning in 2009, the adjusted rates of use increased back up to their pre-warning levels (2.29% in 2003, 2.26% in 2009). The initial impact of the warning differed between the severe and non-severe populations, having a stronger and significant effect on the non-severe population.

Conclusions

The return to the pre-box warning rates raises concern that the impact of the warning may have dissipated over time. An important policy implication of these findings could be that more frequent updates of FDA risk warnings might be necessary.

Introduction

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for protecting public health interests by assuring the safety and security of medications.1 To achieve that goal, the FDA undertakes comparative effectiveness research to determine risks and issue risk warnings when necessary. In October 2004, after conducting a series of meta-analyses and finding an increased risk of suicidality events among paroxetine-treated children, the FDA directed pharmaceutical companies to issue box warnings on antidepressants about the potential link between the use of antidepressants and suicidal ideation among children.2–4 The goal of this paper is to analyze the long-run trends in antidepressant use among children before and after the box warning, and to see if an initial decline in use is followed by a return to rates of use before the warning.

The prescription of antidepressants for children was on the rise along with the diagnoses of depression until 2005, when both prescriptions and diagnoses rates dropped sharply due to the implementation of the box warning.3,5 Initially, the box warning resulted in an overall decrease of antidepressant use for both adults and children.6,7 The trends in antidepressant use in the years immediately following the warning have been studied extensively; however, most studies since then have focused on re-testing the effectiveness and risks of antidepressants for pediatric patients rather than analyzing the long-term effects of the box warning on antidepressant use.8–12 One such study suggested that “meta-analyses fail to undermine evidence that antidepressants are associated with increased risk of suicidality in children”, and that the box warning on pediatric use of antidepressants are warranted.10 On the other hand, Lu et al. identified that while antidepressant use among youth declined, suicide attempts may have actually increased after the box warning,12 suggesting that there may have been unintended negative consequences attributable to overall decline in treatment for depression,3,5 and the decline in antidepressant prescription without the FDA-recommended monitoring and use of alternative treatments.13 Understanding national, long-run trends of antidepressant use acts as an indicator of the strength of the box warning in the midst of conflicting evidence, as well as how providers have reacted to the evolving uncertainty and complexity of youth depression treatment.

Other medication and product warnings have had varied impact on patterns of use.14–17 For instance, FDA warnings regarding antipsychotic use for Parkinson’s disease and ADHD medication for pediatric patients did not result in change or decline of use18 possibly due to the lack of a media campaign.19 Other product warnings (e.g. artificial sweeteners and cigarettes), however, have resulted in sharp drops of product use shortly after a warning, only to be later followed by a renewed increase in product use.20,21 Consumer studies show that warning compliance depends on a variety of consumer factors that are both design and non-design related,22 such as the fact that text labels are more difficult to remember,23 and that for certain products it is more difficult to implement effective advisories.24

Individuals adhere to box warnings depending on the perceived risks and benefits of the product, which is true for both mental health patients25 as well as providers.26 These perceived risks are unrelated to the actual risk or even the proposed risk by a warning label.21,27,28 The level of perceived risk is associated with factors such as the prescribers’ years of experience and gender.26 Legal differences,29 perceived liability,30 and provider knowledge31 may also affect prescription behavior, regardless of the information provided by the box warning. Among consumers, a box warning for antidepressants does increase the perceived risk.32 On the other hand, consumers with prior continuous use might have a reduced perceived risk since continuous use of antidepressants reduces the risk of relapse and recurrence of depression.33 In analyzing perceived risks over time, it is also important to consider the role of the pharmaceutical companies. In response to product sales decreases, pharmaceutical companies have been motivated to downplay warnings after their initial implementation.34

Possibly due to changes in these perceived risks and behaviors, the 2004 box warning appears to have a differential effect on antidepressant use among children in the short-run and the long-run. Analyzing the trends of antidepressant use among children is the first step towards understanding the long-run response of consumers, providers, and manufacturers to risk warnings. In this study, we seek to examine the long-run effect of the box warning on antidepressant use and see whether the impact differs between the severe and non-severe populations. We divide the post-warning years into two time periods, early post (2004–07) and late post (2008–2011) to differentiate the short-run and long-run impact of the warning on rates of use. The cutoff year is chosen as 2007 due to FDA’s revision to the box warning that year, and to better accommodate the initial uncertainty that might have been associated with the 2004–07 time period.

Data

For our analysis, we use data for children aged 5–17 from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), covering years 2000–2011. This age range corresponds to the population targeted by the FDA box warning. MEPS is a nationally representative survey of the non-institutionalized US population. Approximately 15,000 individuals are newly surveyed each year about their health care utilization, demographic characteristics, socio-economic status, and physical and mental health status. Our final sample includes 75,819 children aged 5–17.

Psychological impairment in our analysis is defined using the Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) score, which is reported as part of the MEPS data. CIS is a 13-item global measure of impairment administered to parents by an interviewer. It addresses four areas of functioning: interpersonal relations, broad psychopathological domains, functioning in job or school, and use of leisure time, and has been used in prior trends studies among youth35. Items are scored on a range of 0 to 4, with total scores ranging from 0 to 52. This is a parent-reported instrument that correlates well with the clinicians’ Children’s Global Assessment Scale score.36 We use a cutoff score of CIS≥16 to differentiate children with severe psychological impairment from those without impairment.37

The dependent variable of interest is any antidepressant use at a given year. Using the prescription names listed in the MEPS prescription files, we identified the children with any antidepressant use at a given year. The list of antidepressant prescription names included in our definition can be found in Appendix A1.a,b

The additional covariates used in our models are age, race, gender, income level, insurance status, health status, and metropolitan statistical area (MSA). Age is calculated from date of birth and indicates age status as of December 31st of each year; it is categorized into three groups (5–9, 10–13, 14–17). Insurance status indicates the respondents’ insurance coverage by private insurance, Medicaid/SCHIP or Medicare, other public insurance, or uninsured. Income is denoted as a categorical variable: below poverty (<100% of the federal poverty level or FPL), near poverty (100–125% FPL), low income (125–200% FPL), middle income (200–400% FPL), and high income (>400% FPL). The race variable is coded using three Census-based categories: non-Hispanic White, Black, and Hispanic. Other race and ethnicity groups are excluded from the sample due to small sample size. Health status measures perceived health status, as the respondents were asked to rate their health according to the following categories: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor.

Methods

To estimate the how the impact of warning on antidepressant use among kids changes over time, we first divide the entire sample period (2000–2011) into four time periods: early pre-warning (2000–2001), pre-warning (2002–03), early post (2004–07) and late post-warning (2008–11). Then, we estimate the short-run and long-run impact of the warning on antidepressant use using a multivariate probit model:

| (1) |

where y is any antidepressant use at a given year; X is vector of explanatory variables including gender, age, race, income, health status, insurance status, and MSA; Time is the categorical variable that denotes the time periods of early pre, pre, early post, and late post-warning years, and G(․) is the CDF of standard normal distribution. The main coefficient of interest is β1, which denotes the short-run (early post) and long-run (late-post) impact of the warning compared to the pre-warning years.

Sample years before the warning are divided into two categories early-pre (2000–01) and pre (2002–03), and the pre-warning period (2002–03) is used as the reference category. This is mainly due to the noticeable difference in antidepressant use rates between these two periods, with years 2002–03 right before the warning being more representative of the antidepressant use trends right before the warning.

We used the coefficient estimates from the model in Equation 1 to generate recycled predictions, also called the predictive margins method, to estimate the regression adjusted yearly predicted probability of use.39 The standard errors of the predicted probabilities were estimated using bootstrap methods (N=500).40 In all of our analysis, we adjusted for the sampling design used in the MEPS, including the estimation weight, sampling strata, and primary sampling unit.41 We estimated the probit model in Equation 1 for two subsamples (children with and without psychological impairment) to explore whether the long run effects were different between the severe and non-severe populations. Goodness of fit in all models were verified using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (Appendix A2).38

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the final sample that includes 75,819 children aged 5–17. The children in the sample are balanced in terms of gender (48.9% female), predominantly white (42.0%), and are mostly insured (90.4%). Only 27.7% of the children live in households below the federal poverty level, and 1.5% reported the use of any antidepressants. Among our final sample, 19% of the children (n=14,523) are considered to have severe psychological impairment (CIS≥16), and the remaining 81% are considered non-severe (CIS<16). The prevalence of antidepressant use differs noticeably between the severe and non-severe populations. The prevalence of antidepressant use among the severe and non-severe children are 5.0% and .7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Children Aged 5–17 (2000–2011)

| Severe (CIS*>=16) |

Non-severe (CIS<16) |

p- value |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=14,523 | N=61,296 | N=75,819 | |||||

|

|

|

||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| Female | 6,653 | 45.8% | 30,402 | 49.6% | <0.001 | 37,055 | 48.9% |

| Race | |||||||

| white | 6,529 | 45.0% | 25,349 | 41.4% | <0.001 | 31,878 | 42.0% |

| black | 3,527 | 24.3% | 12,689 | 20.7% | 16,216 | 21.4% | |

| hispanic | 4,467 | 30.8% | 23,258 | 37.9% | 27,725 | 36.6% | |

| Age | |||||||

| 5–9 | 4,762 | 32.8% | 23,311 | 38.0% | <0.001 | 28,073 | 37.0% |

| 10–13 | 4,545 | 31.3% | 19,749 | 32.2% | 24,294 | 32.0% | |

| 14–17 | 5,216 | 35.9% | 18,236 | 29.8% | 23,452 | 30.9% | |

| Insurance | |||||||

| private | 5,228 | 36.0% | 28,369 | 46.3% | <0.001 | 33,597 | 44.3% |

| medicare/medicaid | 7,990 | 55.0% | 26,649 | 43.5% | 34,639 | 45.7% | |

| other | 75 | 0.5% | 233 | 0.4% | 308 | 0.4% | |

| uninsured | 1,230 | 8.5% | 6,045 | 9.9% | 7,275 | 9.6% | |

| MSA | 11,850 | 81.6% | 51,189 | 83.5% | <0.001 | 63,039 | 83.1% |

| Income | |||||||

| below poverty (<100% FPL**) | 4,889 | 33.7% | 16,121 | 26.3% | <0.001 | 21,010 | 27.7% |

| near poverty (100–125% FPL) | 1,182 | 8.1% | 4,951 | 8.1% | 6,133 | 8.1% | |

| low income (125–200% FPL) | 2,769 | 19.1% | 12,005 | 19.6% | 14,774 | 19.5% | |

| middle income (200–400% FPL) | 3,651 | 25.1% | 17,303 | 28.2% | 20,954 | 27.6% | |

| high income (>400% FPL) | 2,032 | 14.0% | 10,916 | 17.8% | 12,948 | 17.1% | |

| Perceived health status | |||||||

| excellent | 5,612 | 38.6% | 30,744 | 50.2% | <0.001 | 36,356 | 48.0% |

| very good | 4,354 | 30.0% | 17,404 | 28.4% | 21,758 | 28.7% | |

| good | 3,371 | 23.2% | 10,891 | 17.8% | 14,262 | 18.8% | |

| fair | 777 | 5.4% | 1,501 | 2.4% | 2,278 | 3.0% | |

| poor | 163 | 1.1% | 159 | 0.3% | 322 | 0.4% | |

| Any antidepressant use | 733 | 5.0% | 421 | 0.7% | <0.001 | 1,154 | 1.5% |

CIS stands for Columbia Impairment Scale.

FPL stands for Federal Poverty Level.

Note: p-values are computed using the Pearson's chi-squared statistic.

The probit regression results are presented in Table 2, which includes estimates for the total sample in addition to the subsamples of severe and non-severe children. Among all children, there is a significant decline of .5% in the probability of using any antidepressants during the early post-warning years (2004–07) compared to pre-warning years after adjusting for all covariates (coef=−.13, p=.01). In the long-run, however, there was no statistically significant difference. In late post-warning years (2008–01), the probability of use was not significantly different than the pre-warning years at any conventional level (p=.33).

Table 2.

Impact of post-warning years on antidepressant use among children (aged 5–17)

| (1) All | (2) Severe (CIS>=16) |

(3) Non-severe (CIS<16) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Coef | SE | Coef | SE | Coef | SE | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Time (pre: 2002–03) | ||||||

| early pre: 2000–01 | −0.16** | 0.06 | −0.24** | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.08 |

| early post: 2004–07 | −0.13** | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.16** | 0.06 |

| late post: 2008–11 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Female | −0.08* | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.05 |

| Race (white) | ||||||

| black | −0.58*** | 0.06 | −0.54*** | 0.08 | −0.64*** | 0.07 |

| hispanic | −0.44*** | 0.06 | −0.44*** | 0.07 | −0.44*** | 0.08 |

| Age (5–9) | ||||||

| 10–13 | 0.49*** | 0.05 | 0.51*** | 0.08 | 0.47*** | 0.08 |

| 14–17 | 0.76*** | 0.05 | 0.73*** | 0.08 | 0.79*** | 0.08 |

| Insurance (private) | ||||||

| medicare/medicaid | 0.18*** | 0.06 | 0.19* | 0.08 | 0.18* | 0.08 |

| other | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| uninsured | −0.44*** | 0.09 | −0.62*** | 0.14 | −0.29** | 0.11 |

| Income (poverty) | ||||||

| near poverty | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.11 |

| low income | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 0.07 |

| middle income | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.24** | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.08 |

| high income | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.23* | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.09 |

| Health status (excellent) | ||||||

| very good | 0.18*** | 0.04 | 0.23*** | 0.07 | 0.15** | 0.06 |

| good | 0.43*** | 0.05 | 0.52*** | 0.07 | 0.33*** | 0.06 |

| fair | 0.65*** | 0.08 | 0.68*** | 0.10 | 0.67*** | 0.11 |

| poor | 0.75*** | 0.16 | 0.87*** | 0.20 | 0.53* | 0.22 |

| MSA | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Constant | −2.91*** | 0.10 | −2.25*** | 0.14 | −2.81*** | 0.12 |

| Severe (CIS>=16) | 0.76*** | 0.04 | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Observations | 75,819 | 14,523 | 61,296 | |||

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Note: Marginal effects for time variable in Model 1 are as follows:

2. early pre: 2000–01 −0.006

3. early post: 2004–07 −0.005

4. late post: 2008–11 −0.002

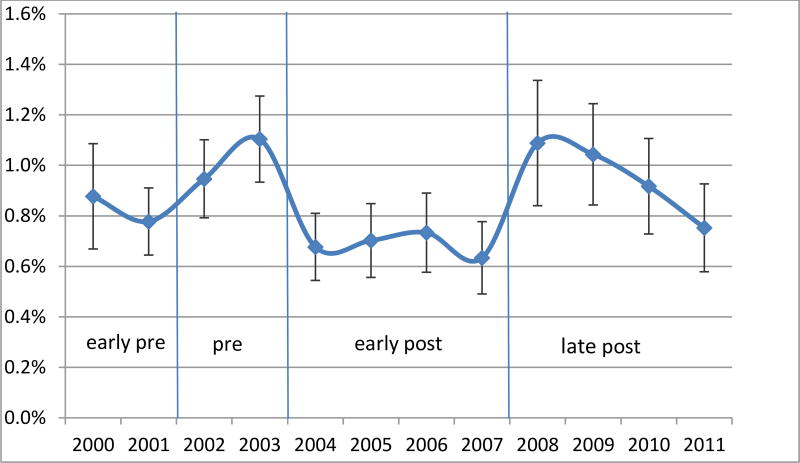

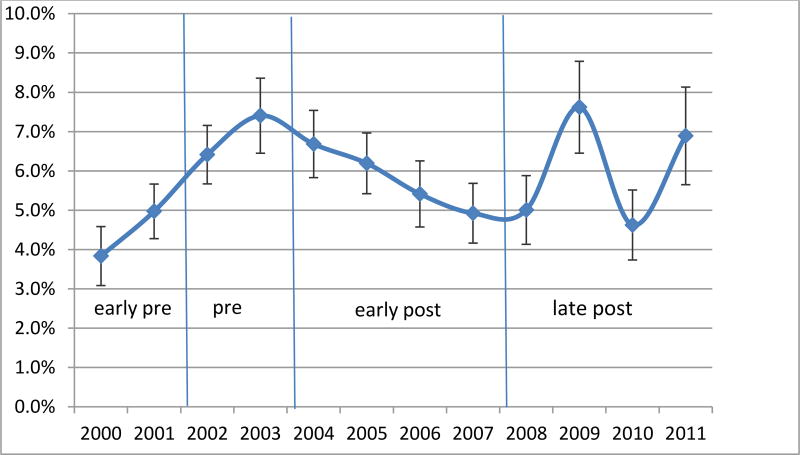

The results also show that short-term impact of the warning differs between the severe and non-severe populations. Among children with severe psychological impairment, there was no significant decline in the probability of using antidepressants during the early post-warning years (2004–2007) compared to the pre-warning years (2002–2003) (p=.17). However, non-severe children were .3% less likely to use antidepressants in the early post-warning years and the effect was significant (coef=−.16, p=.01). Neither the severe nor the non-severe populations showed significant decline in antidepressant use in the late post-warning years (2008–2011) compared to the pre-warning years (2002–2003). In other words, antidepressant use in the late post-warning years did not significantly differ from the pre-warning years in either population.

Figures 1–3 present the regression-adjusted yearly trends in antidepressant use in 2000 to 2011 among the three samples of interest: all children aged 5–17, severe and non-severe children, respectively. Five years after the warning in 2009, the adjusted rates of use increase back up to the pre warning level in 2003 (2.29% in 2003, 2.26% in 2009). The initial decrease in antidepressant use is not prominent among the severe children, as represented by the early-post area in Figure 2. However, we observe an almost perfect U-shaped trend among non-severe children in Figure 3 where antidepressant use rate as of 2008 (1.09%) is almost identical to the pre-warning usage rate of 1.10% in 2003.

Figure 1.

Regression Adjusted Trends in Any Antidepressant Use - All

Figure 3.

Regression Adjusted Trends in Any Antidepressant Use - Non-severe (CIS<16)

Figure 2.

Regression Adjusted Trends in Any Antidepressant Use - Severe (CIS>=16)

As a sensitivity check, we also examined the same trends among the adult population and found no spillover effects of the warning on the adult population. There was no decline in antidepressant rates in the early-post or late-post periods in the adult sample. On the contrary, adults’ rates of any antidepressant use were significantly higher (not lower) than the pre-period in both early-post (2004–07) and late post (2008–11) periods at p<0.001.

Discussion and Conclusions

We found a .5% statistically significant decline in antidepressant use in the years immediately following the box warning, suggesting that the diffusion of risk information was effective at reducing rates of use in the short run. However, the initial impact of the warning seemed to fade away in the long-run, as the prevalence of antidepressant use returned to the pre-warning year levels by 2009. We also found that the initial impact of the warning differed between the severe and non-severe populations. The warning appeared to have a stronger effect on children without severe psychological impairment. As shown by the regression-adjusted annual trends, the U-shaped trend of immediate decrease in use followed by a return to the pre-warning levels is most prominent among children without severe psychological impairment. Among the psychologically impaired population, there was a slight decline in antidepressant use until 2008, but the change in prevalence did not appear as dramatic and was not significant.

These findings suggest that providers and families of youth may have reacted to the box warning in an appropriate manner, weighing the warning in with the risks and benefits of the treatment, and deciding not to use the medication when psychological impairment was low, but choosing to use the medication when impairment was high and the benefits outweighed the risks. A return to the pre-box warning rates raises concern that this thoughtful accounting of the risks and benefits may have dissipated over time. The period of increased caution might have been followed by a return to previous levels after analyzing the newly available information.

An important policy implication of our findings could be that more frequent updates of FDA risk warnings might be necessary to prevent the patients and the providers from “forgetting” the potential risks outlined in the original warning. Methods have been suggested to increase the long-run effectiveness of warnings for both medical and nonmedical products. For example, a study of the warning labels for cigarettes found that designs should be rotated regularly and that they should be simple text accompanied with images.43 Complex advisories are likely to be ignored by consumers and effective advisories should be tailored to specific consumers.44 Label design has a significant impact on warning label effectiveness.45 A careful review of the successes and failures of different consumer advisories can show how to best increase the long-run effectiveness of pediatric antidepressant risk warnings.

One limitation of this study is the methodology used to determine the severity of depression. Even though the Columbia Impairment Scale is commonly used in clinical settings, it is not specific to the assessment of depression severity. The severe psychological impairment indicator we used that was based on the CIS score only serves as a proxy to the respondents’ actual level of severity and need for antidepressants.

An interesting future research question that is not within the scope of this paper is whether the short-run and long-run trends observed in antidepressant use was driven by provider or patient behavior. Some research has suggested that both patient and provider behaviors have changed due to the warning,46–48 but studies have focused mostly on the decreased treatment of depression,5 or the lapses in heeding the box warning in ambulatory services.11 Another related research area is the appropriate clinical reaction to this specific FDA box warning. Rather than simply writing fewer prescriptions, some researchers have advised that the box-warning should concurrently result in increased monitoring of children on antidepressants or an increase in alternatives such as cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal counseling,49 and psychosocial treatment.50

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been partially supported by grant 5R01HS021486-02 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the AHRQ.

Footnotes

This study was presented in part at a poster session at the Fifth Biennial Meeting of the American Society of Health Economists, June 22–25, 2014, Los Angeles.

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

All authors declare no support from any organization for the submitted work other than the AHRQ grant specified above; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

We include a broad list of antidepressants that might sometimes be used for other purposes than depression in children and adolescents.

Bibliography

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed February 18, 2016];About FDA. 2016 http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/default.htm.

- 2.Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Mar;63(3):332–339. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, et al. Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;64(4):466–472. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman TB. A Black-Box Warning for Antidepressants in Children? New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(16):4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, Orton HD, Allen R, Valuck RJ. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;164(6):884–891. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch SH, Barry CL. Pediatric antidepressant use after the black-box warning. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 May-Jun;28(3):724–733. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson K, Price J, Simon KI, Tennyson S. The influence of FDA advisory information and black box warnings on individual use of prescription antidepressants. Review of Economics of the Household. 2014;12(4):771–790. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;17(12):1186–1193. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menke A, Domschke K, Czamara D, et al. Genome-wide association study of antidepressant treatment-emergent suicidal ideation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012 Feb;37(3):797–807. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparks JA, Duncan BL. Outside the Black Box: Re-assessing Pediatric Antidepressant Prescription. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013 Aug;22(3):240–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner AK, Chan KA, Dashevsky I, et al. FDA drug prescribing warnings: is the black box half empty or half full? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006 Jun;15(6):369–386. doi: 10.1002/pds.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. 2014;348:g3596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busch SH, Frank RG, Leslie DL, et al. Antidepressants and Suicide Risk: How Did Specific Information in FDA Safety Warnings Affect Treatment Patterns? Psychiatr. Serv. 2010;61(1):11–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusetzina SB, Higashi AS, Dorsey ER, et al. Impact of FDA drug risk communications on health care utilization and health behaviors: a systematic review. Med Care. 2012 Jun;50(6):466–478. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrenpreis ED, Ciociola AA, Kulkarni PM. FDA-Related Matters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. How the FDA manages drug safety with black box warnings, use restrictions, and drug removal, with attention to gastrointestinal medications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr;107(4):501–504. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrester MB. Effect of cough and cold medication withdrawal and warning on ingestions by young children reported to Texas poison centers. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012 Jun;28(6):510–513. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182587b0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Rasooly I, Brooks G, Pines J, May L, van den Anker J. The impact of pediatric labeling changes on prescribing patterns of cough and cold medications. J Pediatr. 2014 Nov;165(5):1024–1028. e1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weintraub D, Chen P, Ignacio RV, Mamikonyan E, Kales HC. Patterns and trends in antipsychotic prescribing for Parkinson disease psychosis. Arch Neurol. 2011 Jul;68(7):899–904. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry CL, Martin A, Busch SH. ADHD medication use following FDA risk warnings. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2012 Sep;15(3):119–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinhart Y, Carmon Z, Trope Y. Warnings of adverse side effects can backfire over time. Psychol Sci. 2013 Sep;24(9):1842–1847. doi: 10.1177/0956797613478948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wogalter MS, Laughery KR. WARNING! Sign and Label Effectiveness. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1996;5(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laughery KR, Wogalter MS. A three-stage model summarizes product warning and environmental sign research. Safety Science. 2014;61:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strasser AA, Tang KZ, Romer D, Jepson C, Cappella JN. Graphic warning labels in cigarette advertisements: recall and viewing patterns. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Jul;43(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas G, Gonneau G, Poole N, Cook J. The effectiveness of alcohol warning labels in the prevention of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A brief review. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research. 2014;3(1):191–103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spink J, Singh J, Singh SP. Review of package warning labels and their effect on consumer behaviour with insights to future anticounterfeit strategy of label and communication systems. Packaging Technology and Science. 2011;24(8):469–484. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beyer AR, Fasolo B, Phillips LD, de Graeff PA, Hillege HL. Risk perception of prescription drugs: results of a survey among experts in the European regulatory network. Med Decis Making. 2013 May;33(4):579–592. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12472397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wogalter MS, Brelsford JW, Desaulniers DR, Laughery KR. Consumer product warnings: The role of hazard perception. Journal of Safety Research. 1991;22:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wogalter MS, Conzola VC, Smith-Jackson TL. Research-based guidelines for warning design and evaluation. Applied Ergonomics. 2002;33:12. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(02)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoek J, Gendall P, Rapson L, Louviere J. Information Accessibility and Consumers' Knowledge of Prescription Drug Benefits and Risks. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2011;45(2):248–274. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lester P, Kohen I, Stefanacci RG, Feuerman M. Antipsychotic drug use since the FDA black box warning: survey of nursing home policies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011 Oct;12(8):573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salinas GD, Robinson CO, Abdolrasulnia M. Primary care physician attitudes and perceptions of the impact of FDA-proposed REMS policy on prescription of extended-release and long-acting opioids. J Pain Res. 2012;5:363–369. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S35798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gearing RE, Townsend L, MacKenzie M, Charach A. Reconceptualizing medication adherence: six phases of dynamic adherence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011 Jul-Aug;19(4):177–189. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.602560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim KH, Lee SM, Paik JW, Kim NS. The effects of continuous antidepressant treatment during the first 6 months on relapse or recurrence of depression. J Affect Disord. 2011 Jul;132(1–2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mintzes B, Lexchin J, Sutherland JM, et al. Pharmaceutical sales representatives and patient safety: a comparative prospective study of information quality in Canada, France and the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2013 Oct;28(10):1368–1375. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC. Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 May 21;372(21):2029–2038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1413512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983 Nov;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bird HR, Andrews H, Schwab-Stone M, et al. Global measures of impairment for epidemiologic and clinical use with children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1996;6(4):295–307. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. First. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999 Jun;55(2):652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Efron B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. The Annals of Statistics. 1979;7(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machlin S, Yu WY, Zodet M. [Accessed February 18, 2016];Computing Standard Errors for MEPS Estimates. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/standard_errors.jsp.

- 42.Lu CYZF, Lakoma MD, Madden JM, Rusinak D, Penfold RB, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. 2014;348:g3596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tobacco Control. 2011:12. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riley D. Mental models in warnings message design: A review and two case studies. Safety Science. 2014;61:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feunekes GI, Gortemaker IA, Willems AA, Lion R, van den Kommer M. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: testing effectiveness of different nutrition labelling formats front-of-pack in four European countries. Appetite. 2008 Jan;50(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheung A, Sacks D, Dewa CS, Pong J, Levitt A. Pediatric prescribing practices and the FDA Black-box warning on antidepressants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008 Jun;29(3):213–215. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817bd7c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katz LY, Anita L Kozyrskyji, Heather J Prior, Murray W Enns, Brian J Cox. Jitender Sareen. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescription rates, use of health services and outcomes among children, adolescents and young adults. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;178(8):7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piening S, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, de Vries JT, et al. Impact of safety-related regulatory action on clinical practice: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2012 May 1;35(5):373–385. doi: 10.2165/11599100-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wells KB, Tang L, Carlson GA, Asarnow JR. Treatment of youth depression in primary care under usual practice conditions: observational findings from Youth Partners in Care. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012 Feb;22(1):80–90. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gearing RE, Townsend L, Elkins J, El-Bassel N, Osterberg L. Strategies to predict, measure, and improve psychosocial treatment adherence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014 Jan-Feb;22(1):31–45. doi: 10.1097/HRP.10.1097/HRP.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.