Abstract

Objective

The low level of passively diffused IgG through the blood–brain barrier is sufficient to blur the estimation of intrathecal IgG synthesis (ITS). Therefore, this estimation requires a mathematical calculation derived from empirical laws, but the range of normal values in healthy controls is wide enough to prevent a precise calculation. This study investigated the precision of various methods of ITS estimations and their application to two clinical situations: plasma exchange and immune suppression targeting ITS.

Methods

Based on a mathematical model of ITS, we constructed a population of healthy controls and applied a tunable ITS.

Results

We demonstrate the following results: underestimation of ITS is common at individual level but true ITS is well fitted by cohorts; Q IgG increases after plasma exchange; IgG Loc calculation based on Qlim falsely increases when Q Alb decreases; the sample size required to demonstrate a decrease in ITS increases exponentially with larger Q Alb.

Interpretation

Studies evaluating changes in ITS level should be adjusted to Q Alb. Low amounts of ITS could be largely underestimated.

Introduction

Owing to the immune privilege, B cells and plasma cells are virtually absent from the normal central nervous system (CNS). Therefore, synthesis of immunoglobulins (Igs) does not occur in the normal CNS. However, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contains a tiny concentration of blood‐borne Igs reflecting a low‐rate passive diffusion of molecules through the blood–CSF barrier (BCB) to the CSF. It has long been known that although virtually all molecules may diffuse from serum to the CSF, the permeability of the BCB positively correlates with their molecular weight.1 For example, the ratio increases from 1:205 with albumin (65 kDa) to 1:440 with IgG (150 kDa) and 1:900 with IgM (970 kDa).2 Moreover, permeability of the BCB commonly increases during CNS pathologies, leading to an increase in CSF concentrations of blood‐borne proteins and Igs. As a consequence, intrathecally synthesized Igs related to CNS inflammation only increase the CSF Igs concentration, which is nonnull in the basal state. Therefore, direct assaying of Igs in the CSF is obscured by a variable concentration of blood‐borne Igs, so the exact quantification of CSF Igs synthesis requires a mathematical approach taking into account BCB permeability and blood concentrations of targeted molecules.

Quantitative results basically necessitate the subtraction of a putative basal CSF IgG (explained by normal BCB permeability) from the observed abnormal CSF IgG concentration. Since this basal CSF IgG level varies greatly in individual healthy controls, calculations are based on a cut‐off situated at the upper limit of the normal group. Therefore, on an individual level, quantification of intrathecal synthesis (ITS) is intrinsically underestimated by calculation. Cohort studies may minimize this pitfall by using a cut‐off based on the mean instead of the upper limit of the intrathecal concentration. However, the range of the potential underestimation of ITS has never been estimated exactly with these methods.

Patients with polyclonal Ig synthesis, which remains undetected by OCB and at too low a level to increase the IgG index, may be inappropriately classified as being devoid of ITS. This is highly problematic in patients suspected of suffering from non‐MS CNS autoimmune disorders like autoimmune encephalitis since basic CSF findings (cells, OCB, IgG index) are strong supportive clues in the early tentative diagnosis, so they may be required to undergo specific analysis. Moreover, in some cases of autoimmune encephalitis reacting against an unknown antigen, no immunoblot is available to demonstrate a putative intrathecal Ig synthesis. This lack of sensitivity of nonspecific techniques to screen ITS may lead to a greater underestimation of it than commonly thought in various CNS pathologies (i.e., stroke, Rasmussen)3, 4 and animal models of CNS autoimmunity.5, 6, 7 Lastly, although ITS is mainly used nowadays as a surrogate binary clue, decreasing the ITS level may be a valuable goal so the precise monitoring of ITS may become an issue.

We present for the first time a theoretical framework demonstrating and quantifying the intrinsic underestimation of intrathecal Ig synthesis with a mathematical model. Discrepancies between calculated and exact intrathecal IgG synthesis are outlined for both single patient and cohort studies. The influences of IgG level changes on plasma and ITS are examined and the consequences for future studies targeting ITS are summarized.

Theoretical Background

The problem of passive protein transfer toward the BBB

The albumin quotient (or ratio), Q Alb = [AlbCSF]/[Albserum], is a widely used parameter of BCB dysfunction that increases with its permeability and is influenced by age and underlying CNS pathologies. Normal maximal Q Alb is calculated by the formula: (4 + age(years)/15) × 10−3 and is usually less than 10(×10−3). In the basal state, which is devoid of intrathecal IgG synthesis, CSF IgG levels exclusively depend on the passive diffusion of blood IgG. Therefore, the ratio [IgGCSF]/[IgGserum] is proportional to Q Alb. Supposing a linear relation, Link et al. defined the IgG index = Q IgG/QAlb, with normal values <0.7.8 However, this linear cut‐off did not precisely take into account either normal Q IgG variance or nonlinear correlation with Q Alb (ITS may be under‐ or overestimated depending on low or high Q Alb). Moreover, since Q Alb increases with age, the IgG index is thought to decrease mechanically without any change in ITS.9 In fact, data are best fitted by an empiric hyperbolic function (the “Reibergram”),10 whose constant parameters were later improved thanks to a large dataset of 4154 control patients (supposed to be) devoid of ITS.11 Basically, the notion of hyperbolic function of quotients is based on the concept of decreased CSF flow rate, with the dual effect of a decrease in CSF volume flow and an increase in time to protein transfer, and “dysfunction of the BCB” is equivalent to a reduced CSF flow rate. Therefore, hyperbolic function is the application of Fick's laws of diffusion applied to albumin and Igs.11, 12

Normal basal Q IgG (Q IgG_basal) is variable and cannot be exactly calculated in the event of ITS

In normal patients, all the IgG molecules in the CSF are passively diffused from blood. For a given Q Alb in a population of normal patients, the distribution of Q IgG follows a normal law around the mean curve: Q mean = f(Q Alb) (Fig. 1A). The variance of Q IgG defined by [(Q Lim – Q Low)/Q mean] is about 0.91 for each Q Alb. 11 Individual variations in the diffusion pathway and CSF flow have been given as tentative explanations of this individual Q IgG variability.11

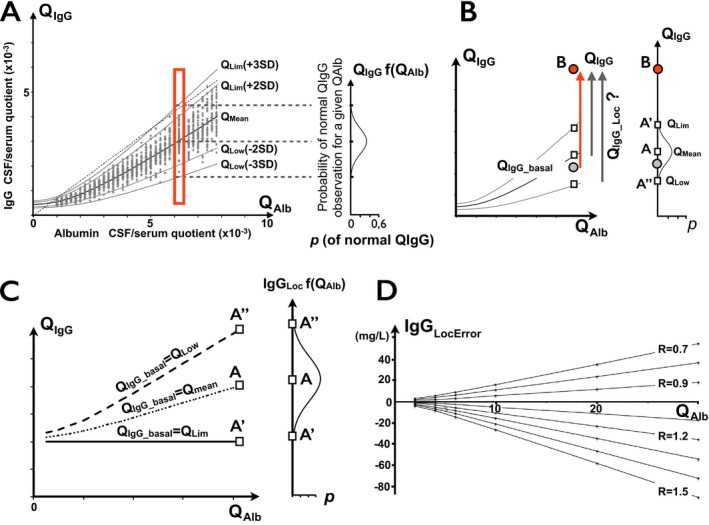

Figure 1.

(A) CSF IgG passively diffused from blood to CSF in normal population. Plot of CSF/serum quotients with hyperbolic function of quotient ratios (“Reibergram”). Reference range defined by QL im = Q mean ± 2SD or ±3SD involving 96% and 99% of normal population, respectively. Dotted line is upper normal limit (>0.7) of IgG index, intersecting QL im curve at two points. Right insert: probability curve of basal QI gG for a given QA lb. The maximum probability is obtained for Qmean. Points are obtained from a simulated healthy population. (B). Range of calculated intrathecal IgG synthesis depending on basal QI gG estimation. True IgGL oc should be calculated based on normal QI gG_basal preceding disease onset (gray circle), which is unknown. In practice, QI gG_Loc, and therefore, IgGL oc, strongly depend on choice of possible QI gG_basal. By raising point B as a definitely abnormal QI gG (≫QL im), the range for the ratio of intrathecally synthesized IgG depends on estimation of basal (before disease onset) QI gG_basal. In individual patients, QL im(+3SD) (point A’) is usually used as an approximation of basal QI gG_basal. However, the true QI gG_basal may be anywhere on the segment A’ – A’’, with the highest probability closest to Q mean at point A. Therefore, quantitative estimation of IgG synthesis IgGL oc=(QI gG – QI gG_basal) x [IgGserum] is strongly influenced by arbitrary choice of QI gG_basal. (C) IgGL oc depending on basal QI gG estimation. IgGL oc(Lim3SD)= 20 mg/L, IgGL oc(mean) ≈ 43 mg/L. Therefore, the true IgGL oc of QI gG(B) is in the range of 20–65 mg/L. Using point B at QI gG=QL im(3SD) + 2 and [IgGserum] = 10 g/L. (D) Error range of IgGL oc calculations assuming various R ratios (R=QI gG_norm/QI gG_basal). A ratio of 1.5 is equal to QL im3SD/Q mean. Calculations assume that [IgGserum] = 10 g/L and QI gG_basal = Q mean.

In the event of ITS, the IgG concentration in the CSF is the sum of the IgG passively diffused from blood and intrathecally synthesized IgG. The relation therefore becomes:

| (1) |

where Q IgG_basal is the putative Q IgG of the same patient before the onset of ITS (Fig 1B). In clinical practice, only Q IgG is directly available but not Q IgG_basal or [IgGCSF_Loc], which may only be approximated by the choice of the discrimination curve of Reiber.

The mean Q IgG among the normal population (therefore the mean Q IgG_basal) is defined by the Q mean curve. The upper limit of the reference range, Q Lim, is usually arbitrarily fixed as Q mean + 3SD and involves >99% of the normal population. Using this definition, intrathecal IgG synthesis is acknowledged when Q IgG > Q Lim. Q Lim is commonly fixed at Q mean + 3SD, since in the latter case only <1% of healthy controls may display a Q IgG > Q Lim, giving a very high specificity to abnormal Q IgG values. A major drawback of this reference range is a loss of sensitivity in cases displaying a low level of ITS (Q IgG > Q IgG_basal but Q IgG ≤ Q Lim). In common practice, demonstration of ITS in these cases requires a CSF‐restricted OCB positivity. As expected, restriction of the reference range to Q Lim + 2SD instead of +3SD, although increasing the risk of false positivity (4% of normal outside this range), increases the percentage of abnormal Q IgG in MS cohorts by 6–10% for IgG and up to 20% for IgM.9

Underestimation bias of local IgG synthesis –the “silent ITS”

The true amount of intrathecally (or locally) synthesized IgG should be calculated as:

| (2) |

Since Q IgG_basal is an unavailable parameter, a Q IgG_norm replaces it, assuming Q IgG_norm = Q Lim or Q mean. As previously demonstrated, replacing Q IgG_basal by Q Lim confers a maximum of specificity in single patient studies, with the drawback of unavoidable underestimation of ITS. Replacing Q IgG_basal by Q mean is interesting since the probability of being close to the exact Q IgG_basal is higher. The main drawback is the false positivity of an ITS in one half of cases (having Q IgG_basal > Q mean) and a negative result in the other half (having Q IgG_basal < Q mean), so this method of calculation is not suitable at an individual level. By contrast, this approximation is allowed and is more precise in patient groups since differences in Q IgG_basal around the Q mean are compensated by the size effect of the cohort.9

The range of IgGLoc is variable and always underestimated, depending on the Q IgG_basal assumption, with the maximum of probability of IgGLoc under the assumption of Q IgG_basal = Q mean. Underestimation of IgGLoc is proportional to Q Alb (Fig. 1B, right panel). In the case of Q IgG = Q Lim(+3SD) (ΔQ IgG = 0), IgGLoc, based on Q Lim calculation, is estimated to be null in single individuals but the underestimation falls within the range of 0 to 106 mg/L, in the Q Alb interval 1 to 20 × 10−3. With higher ΔQ IgG, IgGLoc increases, whereas the absolute value of IgGLoc underestimation remains unchanged. As a consequence, this underestimated “silent” ITS can be closely approximated with a high level of probability by using Q mean.

In general, the calculated amount of locally synthesized IgG may be expressed as:

| (3) |

with IgGLocError = (Q IgG_basal–Q IgG_norm) x [IgGserum]. It is therefore easy to demonstrate that the error in calculating IgGLoc is proportional to Q IgG_basal x (1–R), where R is the ratio of the Q IgG_norm and the true Q IgG_basal (i.e., R = Q Lim3SD/Q IgG_basal ≅ 1.5). IgGLocError is null when Q IgG_basal is known (during simulation). On the other hand, although the range of IgGLocError variations remains negligible for the lowest values of R, substantial amounts are concerned for higher values of R (Fig. 1C).

The fraction of intrathecal Ig from local synthesis, IFIgG (in percent), is the proportion of locally synthesized IgG among the full IgG concentration in the CSF. Theoretically, this fraction should be null only if local IgG synthesis is absent. However, based on the limitation described above and on the common assumption that Q Lim ~ Q IgG_basal, IFIgG is calculated as:

| (4) |

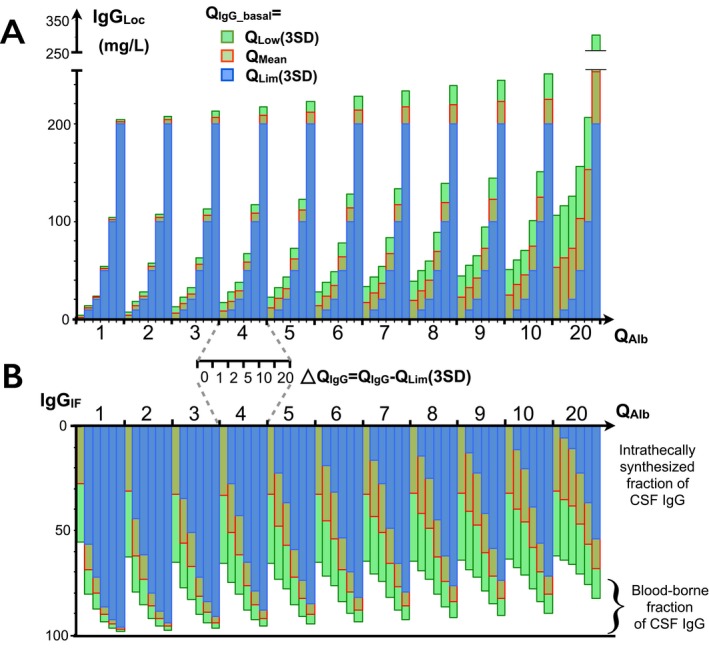

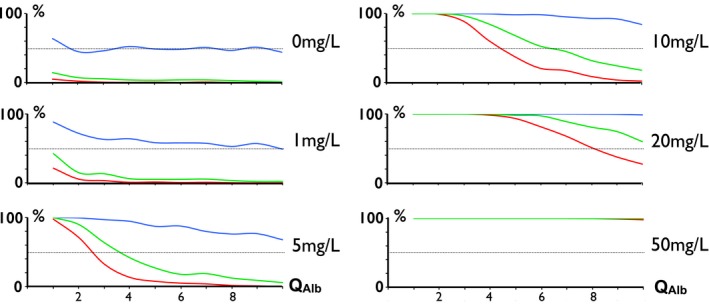

Therefore, in the event of null IgGLoc, although IFIgG is calculated to be 0%, the maximum probability of the true IFIgG in an individual patient is about 30% (0–65%) of the intrathecal fraction of IgG (Fig. 2). Interestingly, this fraction of “silent ITS” is higher for the lowest Q IgG and increases along the Q Alb axis. For Q Alb ≥ 4, the true IFIgG is close to twice that of the calculated IFIgG, and about thrice for Q Alb ≥ 7. The main consequence is that the fraction of “silent ITS” may be nonnegligible and even be major in the event of low Q IgG.

Figure 2.

Influence of choice of basal IgG on estimation of intrathecal IgG synthesis. Calculations are provided for six levels of QI gG increase above QL im (3SD) from ΔQI gG = 0 to +20 mg/L and for each QA lb from 0 to 20 × 10−3. Results of three formulas are displayed: formula applied to individual results: QI gG_basal = Q lim(3SD) (blue); formula for cohort studies, QI gG_basal = Q mean (red); and maximum expected value (at 99%) when QI gG_basal = QL ow (green). Distribution of probability of exact value is centered by red bar. (A) IgGL oc. Underestimation of IgGL oc is highest for the lowest increase of QI gG (0 to +2) above QL im, and increases with higher QA lb. (B) Intrathecal fraction of IgG synthesis. The most probable intrathecally synthesized fraction of CSF IgG is far higher than estimated, especially for low ΔQI gG and high QA lb. For example, with QA lb = 5 and ΔQI gG = 1, IFI gG% is probably about twice that of the expected value (47% vs 22%).

Calculations are tuned by PLEX in the presence of a nonnull ITS

Healthy controls (no ITS)

PLEX lowers serum Ig levels but is not thought to modulate Ig synthesis either in the peripheral compartment or in the event of ITS. Therefore, CSF concentrations of locally synthesized Ig should not be affected. Moreover, the effect of PLEX on serum Ig levels is major but transient, depending on the synthesis rate and half‐life of Ig. Since a large fraction of CSF IgG is passively diffused from the serum, a drop in serum IgG level should decrease the CSF IgG level. On the other hand, the IgG index may mechanically increase since [IgGserum] is the denominator of the fraction. However, for a concentration equilibrium, [IgGCSF] = f([IgGserum]), meaning that both terms of Q IgG are to be simultaneously modified. In fact, a null concentration of serum IgG should be associated with a null CSF concentration.

Diffusion from serum IgG to CSF is modeled by Fick's law which uses a constant of diffusion thought to be a consequence of anatomical microstructures underlying the diffusion pathway and specific to each patient.11 Therefore, Q IgG is a constant for a given patient at a given BCB physiologic state, irrespective of [IgGserum]. As a counterintuitive consequence, although [IgGserum]’ decreases after PLEX, both QIgG and IgG indexes remain constant in the absence of ITS:

| (5) |

so the predicted new level of CSF IgG is: [IgGCSF]’ = Q IgG_basal x [IgGserum]’.

Patients with ITS

The problem gains in complexity if a substantial amount of IgG is synthesized in the CSF. Let us now suppose a constant amount of locally synthesized IgG (IgGLoc). In the equilibrium state (before lowering [IgGserum]):

Therefore, after lowering the initial [IgGserum] to a lower [IgGserum]’:

| (6) |

As a consequence, Q IgG’ increases proportionally to the right term of the equation (6), Q IgGLoc’. In other words, a decrease in serum IgG dramatically tunes the contrast between locally synthesized and passively diffused CSF IgG. Changes in serum albumin level, in association with PLEX, poor physiological condition or chronic infection do not modify Q Alb. 12, 13

Closing the BCB increases QIgG although true ITS remains unchanged

The amount of passively diffused IgG from blood to CSF depends on BCB permeability, so restricting the latter mechanically decreases both Q Alb and Q IgG. The corresponding point on the Reibergram shifts left of the normal curve range. In the event of significant ITS, a level of complexity is added by the dual origin of Q IgG (Eq. (1)), where only Q IgG_basal decreases whereas Q IgG_Loc remains constant. This change tunes the contrast of ITS among the IgG CSF concentrations and may shift apparently normal Q IgG values outside the normal range (Fig. 3).

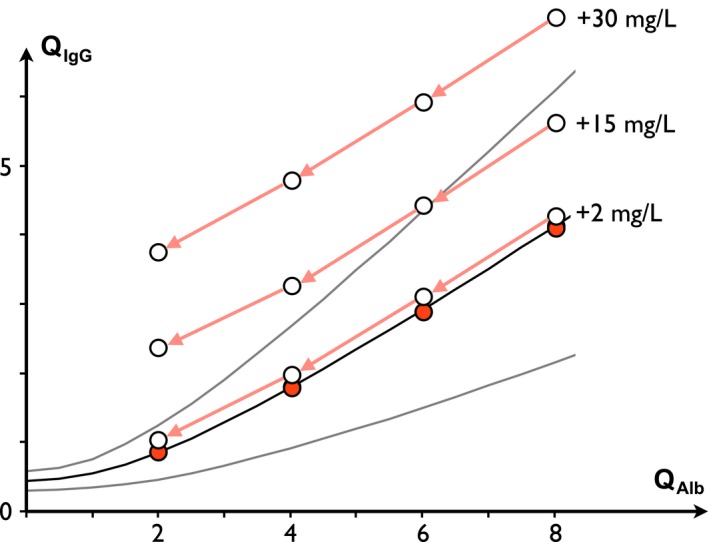

Figure 3.

Evolution of QI gG with decreasing QA lb and at constant ITS. QI gG_basal (red circles) is arbitrarily fixed as equal to Q mean and three examples of constant ITS levels are depicted (2, 15, and 30 mg/L). QI gG decreases as QA lb decreases. Since the variance of normal QI gG is skewed for lower QA lb, the QI gG values associated with an ITS may progressively reach an abnormal range as long as QA lb decreases. IgG index increases as QA lb decreases.

The IgG index always increases in response to closure of the BCB. For example, in response to a decrease from Q Alb(×10−3) = 8 to 2, the IgG index increases from 0.89 to 1.92 at ITS = 30 mg/L. Therefore, an apparently low or normal IgG index may become abnormal without any increase in the former ITS in response to the normalization of the BCB (i.e., recovery of CSF flow rate).

Moreover, calculation of IgGLoc, which is based on Q Lim(3SD) for single patient calculation, may incorrectly confirm this apparent onset of ITS, whereas calculation based on Q mean is accurate.

Material and Methods

Construction of a mathematical model of intrathecal IgG synthesis

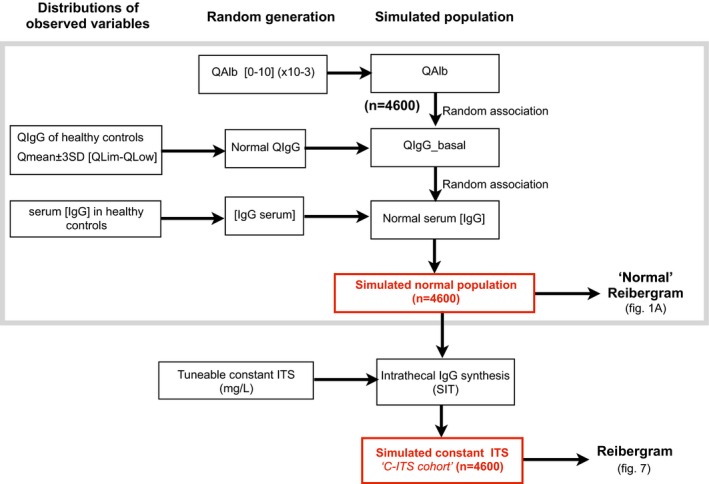

As demonstrated above, ITS is underestimated both in qualitative and quantitative terms. Although it is possible to assess it approximately, the true ITS of patients cannot be measured or calculated unless Q IgG_basal is known. Therefore, using a simple mathematical model based on the abovementioned assumptions, we simulated a population of healthy controls and obtained a model of a normal Reibergram (Fig. 1). We then used this simulated healthy population to construct a cohort with a constant (tuneable) ITS (C‐ITS cohort) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Construction flowchart of mathematical model simulating IgG concentration in populations of healthy controls and patients with constant intrathecal synthesis (C‐ITS cohort).

Statistics

Random values were obtained with StatPlus (AnalystSoft Inc., v5) and used to construct the dataset. All data were processed on Excel (Microsoft Corp., v14). The chi‐squared test was used to compare qualitative variables. The t‐test for paired samples was used for quantitative variables since Q IgG and IgGLoc follow a normal rule. P value for statistical significance was set at 0.05. Calculations of sample size and statistical calculations were made with JMP (SAS Institute Inc., v8.0.2). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve estimation and area under curve (AUC) (95% confidence interval, CI) were calculated with XLSTAT (Addinsoft, v19.7).

Results

Effects of variable levels of intrathecal IgG synthesis on estimated parameters of synthesis

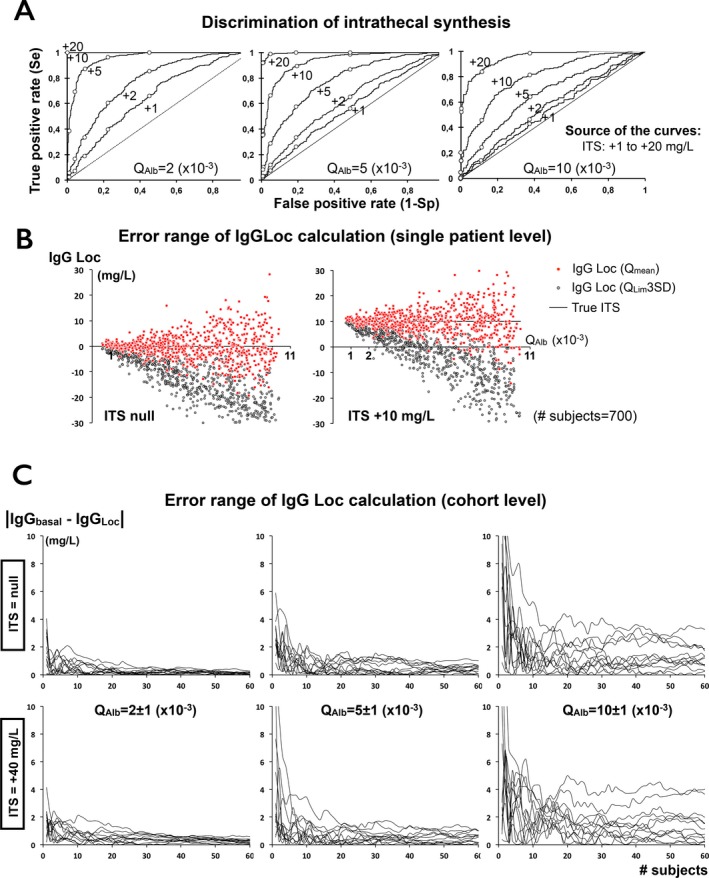

Using the C‐ITS simulated population, ROC curve estimations were obtained for various levels of ITS at different Q Alb (Fig. 5A). AUC increased along with ITS but was inversely proportional to Q Alb. Low amounts of ITS were poorly discriminated at high Q Alb. At single patient level, estimation of true IgGLoc was poor and IgGLoc(Lim) was highly unreliable (Fig. 5B). We compared true IgGLoc values with the results obtained at a cohort level using the various possible calculations (not shown). A correct approximation of the true IgGLoc was systematically obtained for calculations based on Q Mean, even with IgGLoc levels lower than 1 mg/L. On the other hand, estimations of IgGLoc based on Q Lim at 2SD or 3SD gave arbitrary results. Moreover, the precision of the results based on Q Mean was independent from Q Alb, whereas estimation based on Q Lim was strongly biased (results not shown). However, calculation of IgGLoc(mean) based on the simulation of small cohorts of patients demonstrated that the speed of convergence of IgGLoc was independent from the true ITS and inversely proportional to Q Alb (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Estimation of intrathecal synthesis. (A) ROC curve for various amounts of ITS and different QA lb indicating sensitivity (Se) and specificity to discriminate ITS from normal QI gG. Points from left to right give Se and Sp of IgG index, QL im(3SD), QL im(2SD), QL im(1SD), and Q mean. All AUC except one (ITS +1 mg/L at QA lb 10) are significantly different from 0.5. Low amounts of ITS are poorly discriminated by Reibergram except at very low values of QA lb. For example, AUC of ITS +5 mg/L decreases from 0.954 (0.941–0.966) at QA lb=2 to 0.667 (0.624–0.710) at QA lb=10. (B) At single patient level, calculation of IgGL oc remains unreliable, especially based on QL im. (C) Convergence of the error range (in absolute value) of IgGL oc calculation at a cohort level. Convergence toward the exact ITS value is independent from amount of ITS, but strongly depends from QA lb. Fewer than 10 patients are required to compensate extreme outliers. Formula is: |mean(IgGL oc_true) – mean(IgGL oc calculated)|. For each condition (QA lb; ITS), up to 60 subjects are included in 12 independent simulated assays.

The proportion of abnormal Q IgG strongly depended on the ITS level and the Q Alb (Fig. 6). For a null ITS (normal state), about half of the Q IgG were situated above the Q Mean and almost none were higher than Q Lim. However, at ITS levels as low as +1–5 mg/L, the distribution of Q IgG was strongly biased above Q Mean with the lowest Q Alb. For example, for an ITS as low as +5 mg/L, 95% of the Q IgG were higher than Q Mean, whereas only 13% were higher than Q Lim + 3SD (with Q Alb = 4 × 10−3). As a consequence, the population bias Q IgG > Q Mean is characteristic of a low level of ITS.

Figure 6.

Proportion of QI gG (from C‐ITS cohort) above curves: Qmean (blue), QL im2SD (green), and QL im3SD (red) for various levels of ITS. At a cohort level, a shift of QI gG above the mean is more sensitive of an abnormal low‐grade ITS than suggested by the proportion of patients with QI gG > QL im3SD. As an extreme example, with an ITS of 5 mg/L for QA lb= 5(×10−3), almost all patients are QI gG > Q mean, whereas a few are QI gG > QL im3SD.

Simulation of CSF parameters after plasma exchange (PLEX)

Interestingly, lowering the IgG level tunes the IgG index and Q IgG with an unexpected sensitivity. An increase in IgG index is even predicted for extremely low levels of ITS (1 mg/L) when [IgGserum] is decreased by more than 90%. For an ITS value of 10 mg/L (Q IgG remains under Q Lim), a minimal decrease in [IgGserum] of 20% is sufficient to turn the IgG index and Q IgG into abnormal values. Results obtained for common ITS values and PLEX outcome are listed in Table 1. Note that when [IgGserum] was lowered even more, the fraction of IgGCSF in CSF became substantial even at very low ITS rates (i.e., up to 30% of IgGCSF is of local origin for ITS = 1 mg/L and PLEX rate = 90%). Interestingly, after a PLEX procedure depleting [IgGserum] by 90%, [IgGCSF] became almost a pure product of locally synthesized IgG.

Table 1.

Main CSF parameters after lowering serum IgG level by plasma exchange (PLEX)

| [IgGserum] | True ITS (IgGLoc) (mg/L) | [IgGCSF] (mg/L) | IgG index | Q IgG (×10−3) | IgGLoc (Lim) (mg/L) | True IFIgG (%) | Estimated IFIgG (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before PLEX | 0 | 23 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 24 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0 | 4.2 | 0 | |

| 5 | 28 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 0 | 17.9 | 0 | |

| 25 | 48 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 13.2 | 52.1 | 27.5 | |

| 50 | 73 | 1.5 | 7.3 | 38.2 | 68.5 | 52.4 | |

| −20% | 0 | 18.4 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 19.4 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0 | 5.2 | 0 | |

| 5 | 23.4 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 0 | 21.4 | 0 | |

| 25 | 43.4 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 15.5 | 57.6 | 35.9 | |

| 50 | 68.4 | 1.7 | 8.6 | 40.5 | 73.1 | 59.3 | |

| −50% | 0 | 11.5 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 8.0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 16.5 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 0 | 30.3 | 0 | |

| 25 | 36.5 | 1.5 | 7.3 | 19.1 | 68.5 | 52.4 | |

| 50 | 61.5 | 2.5 | 12.3 | 44.1 | 81.3 | 71.7 | |

| −90% | 0 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 0 | 30.3 | 0 | |

| 5 | 7.3 | 1.5 | 7.3 | 3.8 | 68.5 | 52.4 | |

| 25 | 27.3 | 5.5 | 27.3 | 23.8 | 91.6 | 87.3 | |

| 50 | 52.3 | 10.5 | 52.3 | 48.8 | 95.6 | 93.3 |

Simulation with various levels of true ITS (from null to 50 mg/L). Q IgG_basal = Q mean is used for the sake of clarity. Starting parameters: Q Alb = 5 × 10−3; Q IgG_basal = 2.3 × 10−3; Q Lim(3SD) = 3.47 × 10−3; [IgGserum] = 10 g/L. Results initially abnormal or becoming abnormal after PLEX are in bold. In the event of null ITS, IgG index remains normal throughout PLEX procedures, whereas if ITS is raised to 5 mg/L (see Fig. 7), IgG index becomes abnormal when basal [IgGserum] is reduced by 50%. Estimated IFIgG increases from 0% to 52% for a 90% decrease in basal [IgGserum].

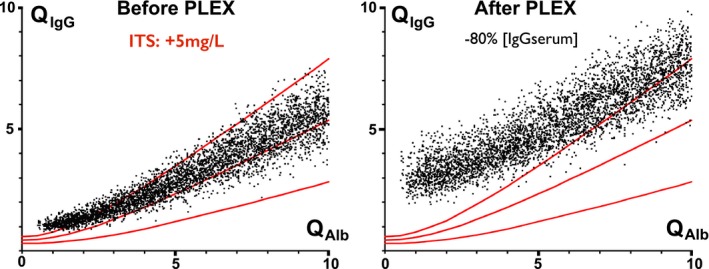

Simulations of PLEX in the C‐ITS cohort are depicted in Figure 7. PLEX increased Q IgG as well as the dispersion of the values. In both examples, the ratio of the IgG index before and after PLEX increased 1.8‐ and 2.7‐fold, respectively, after a procedure decreasing [IgGserum] by 80%. Note that the precision of the IgGLoc estimation remained unchanged after PLEX.

Figure 7.

PLEX effect on QI gG. (Left) C‐ITS population (+5 mg/L). QI gG with low QA lb are slightly increased to abnormal range. (Right) QI gG are increased and in abnormal range. Mean IgG index is increased 1.8‐fold (up to ×3.6).

Consequences for sample size determination in future studies aiming to quantify ITS variations

We provide an estimation of the minimal sample size required to demonstrate a decrease in ITS (Table 2). In the C‐ITS cohort, the standard deviation of IgGLoc(mean) was stable whatever the fixed variations of the ITS level, but it increased collinearly with Q Alb levels (1.7–8.7 in the Q Alb interval 2–10 × 10−3). Therefore, the sample size depends on the distribution of Q Alb in the tested population. Sample size estimations are provided for a range of ITS variations depending on Q Alb. The demonstration of very low synthesis rates remains challenging unless large cohorts can be assembled.

Table 2.

Sample size estimation according to ITS changes and Q Alb strata

| Q Alb (×10−3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| IgGLoc SDa (mg/L) | 1.7 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 8.7 |

| Estimated sample size for ITS variation of: | ||||

| 1 mg/L | 93 | 387 | 756 | 2379 |

| 5 mg/L | 7 | 18 | 33 | 98 |

| 10 mg/L | 4 | 7 | 10 | 26 |

| IgG index (SD) | ||||

| Basal | 0.42 (0.08) | 0.45 (0.08) | 0.48 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.08) |

| +ITS 10 mg/L | 0.94 (0.16) | 0.69 (0.1) | 0.65 (0.08) | 0.62 (0.08) |

| Estimated sample size: | 6 | 7 | 10 | 23 |

Sample size is estimated to detect a difference with a power of 80% at P = 0.05.

SD of IgGLoc are similar whatever the level of basal ITS.

Discussion

A comprehensive theoretical analysis of the diffusion law from blood to CSF was proposed by Reiber et al.10, 11 who provided an elegant mathematical formulation now widely used to quantify absolute and proportional ITS, a criterion used as supportive evidence to diagnose autoimmune and infectious disorders. Unfortunately, this method fails to demonstrate Igs synthesis in up to 21–39% of MS cases9 and in up to 90% of paraneoplastic disorders.14 In the latter, a minor ITS is regularly demonstrated by techniques such as oligoclonal bands (OCB) measured by isoelectric focusing and immunoblotting against various antigens. Unfortunately, these extremely sensitive techniques provide only qualitative information so there is still a “gray zone” where ITS is qualitatively supported by OCB but remains lower than the quantitative cut‐off.

Intrathecal IgG synthesis is often expressed in a binary manner where CSF is considered to be positive if either the IgG index or CSF‐specific oligoclonal bands are observed. Since OCB sensitivity is higher than the two quantitative criteria (IgG index or Q IgG), thorough examination of these criteria for establishing the ITS level is largely neglected. Since the pioneering work of Reiber et al., it is now known that the relation of Q IgG to Q Alb is a nonlinear curve.12, 15 While methods for quantifying ITS (IgGLoc) have been largely debated and several formulas have been proposed,16, 17 the formula derived from the Reibergram remains the best approach although it provides only an approximation.12 However, as we demonstrate above, whatever the choice of Q Lim cut‐off, results concerning “silent ITS” remain mostly unchanged: that is ROC curves calculated (not shown) with the procedure described by Auer et al.17 are very close to those obtained with Reiber's formula.

“Silent ITS” is a common feature in MS, since up to half of the patients demonstrate Q IgG below the Q Lim. Therefore, follow‐up of ITS in these patients could be a challenge. We demonstrate that, at an individual level, approximation of the range of ITS is limited to a statistical approach. We show that when this formula is applied to a single patient (using Q Lim as an approximation of the basal state), ITS is constantly and substantially underestimated, especially at the lowest levels of ITS. Moreover, when a single patient undergoes serial CSF analysis, successive approximations of ITS may give the misleading impression of changes in ITS. For example, if Q Alb is decreased by a treatment “closing” the BCB, the apparent ITS may increase although the true ITS remains unchanged. In a given patient undergoing serial CSF examinations, the apparent change in or onset of ITS should be carefully interpreted if Q Alb decreases. In this case, the calculation of IgGLoc should not be based on Q Lim but rather on Q mean, which minimizes the risk of error.

Q Alb in MS patients is sometimes slightly higher than expected with age, but evolution of Q Alb during the course of MS is poorly known, except for a regular increase due to aging. Higher values of Q Alb are associated with poor outcome.18, 19 Q Alb remained unchanged after various drug treatments (steroids,20 fingolimod,21 natalizumab22), but decreased after pulsed high‐dose steroids,23, 24 natalizumab,25, 26, 27 and mitoxantrone.28 In some cases, the IgG index may paradoxically increase as predicted in relation with a decreasing Q Alb. 24 Therefore, quantification of ITS may often be related with Q Alb and IgGLoc(mean) should be used. Moreover, given the increasing dispersion of values as Q Alb increases, the sensitivity of the traditional approximation decreases as long as Q Alb increases. Therefore, while an ITS of 1 mg/L is easily detected with the lowest Q Alb, a very large cohort is required to detect it when Q Alb = 10(×10−3). On the other hand, we confirm that the use of formulas using Q Mean in a cohort of patients provides a correct approximation of the exact IgGLoc, although convergence below ±2 mg/L is slow in higher Q Alb.

Interestingly, this underestimation of intrathecal IgG synthesis is higher than the common range of many monoclonal antibody (mAb) concentrations required for biological activity, which are usually between 0.1 and 1 mg/L. Therefore, the amount of intrathecally synthesized IgG is sufficient to obtain a biological effect, even in the lower range of underestimated IgG synthesis. In other words, concentrations of intrathecally synthesized IgG may reach the required lower limit for biological activity in the CSF long before any ITS is detected. Moreover, antibodies directed to extracellular targets and with predictable biological activity are retained in brain tissues.29 Recent data suggest that autoreactive antibodies spilling over from the blood at a low level owing to an intact BCB may be completely cleared from the CSF by adsorption on CNS targets.30, 31

As a secondary outcome, we examined how to decipher ITS variations in two common clinical situations: plasma exchange (affecting serum IgG levels) and immune suppression targeting intrathecal IgG synthesis. Few data on this issue are available in the literature and the reliability of ITS measures obtained from patients after PLEX or immunosuppression is unknown.

We previously demonstrated that PLEX treatment reduces serum IgG levels and tunes CSF to an almost pure locally synthesized IgG level. The levels of antineuronal antibodies in serum and CSF before and after PLEX dropped only in serum, whereas CSF levels remained unchanged, but QAlb and QIgG were not reported.32, 33 The IgG CSF/serum ratio increased after PLEX in most cases (anti‐Yo and anti‐Hu). In natalizumab‐treated MS patients treated by PLEX in relation with a progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML), IgG index increased34 and the activity index (AI) against JCV increased 4‐fold.35 Although a rebound of local IgG synthesis induced by PML‐immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) could not be excluded, these results are in line with the predicted outcome of ITS after PLEX. However, in a single patient suffering from limbic encephalitis with ITS of multiple autoantibodies, variations in antibody indexes were heterogeneous and unpredictable in response to PLEX and add‐on steroid treatments.36 As a consequence, aside from the predictable biological effect of PLEX, one should keep in mind that ITS is highly dynamic in most clinical situations, obscuring the effect of PLEX by a simultaneous unpredictable modification of ITS (i.e., increasing during an early ongoing inflammatory process and abating after steroid therapy).

Moreover, our results are based on the calculation of steady‐state concentrations, which are supported by the dynamics of IgG (slow variations in blood, high CSF turnover). Delays to reach a new steady state after abrupt changes in BCB permeability or blood IgG concentrations are thought to be short but remain unknown. High doses of IgG (i.e., rituximab) injected in CSF are completely washed‐out in less than 2 days.37 Moreover, about half of the whole‐body IgG is distributed in the interstitium (extravascular compartment) and the transcapillary escape rate (the transfer rate from the extra‐ to intravascular compartment) is about 3% per hour of the intravascular mass.38 Therefore, the steady state of IgG levels in blood is obtained in approximately 2 days39 and returns to pre‐PLEX levels in a few weeks. Therefore, we consider that 2 days are sufficient to reach a steady state of IgG levels in blood and CSF. CSF drawn the day after PLEX still shows an IgG level suggestive of a former higher level of blood IgG, which may erroneously suggest the occurrence of ITS. In a study including 41 patients treated by PLEX, the IgG index was increased in 19% before PLEX, in 95% at day 1 post‐PLEX, in 25% at day 2 and in 5% later.40 Although 63% of these patients were suffering from Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), only a few of them also had multiple sclerosis, paraneoplastic cerebellitis or autoimmune encephalitis, which are all known to be associated with low level ITS. Considering our results, one cannot rule out that this apparently spurious ITS, especially in patients tapped at day 2 or later, may reveal a low level of true ITS. Madzar et al.41 provided CSF details from a single patient that allowed recalculation of Q IgG. Their findings indicated a low level of ITS occurring in association with biases from nonsteady IgG concentrations. Future studies are required to decipher this hypothesis.

GBS is not usually considered to be associated with ITS.42 OCB are sometimes reported but are identical between blood and CSF (type 4, indicating passive transfer).43 Considering the very high Q Alb values observed in GBS (in the range of 20–80 × 10−3), “silent ITS” could be more common than usually thought. Indeed, specific ITS was demonstrated for IgG against various antigens (αB‐crystallin,44 gangliosides,45, 46 galactocerebrosidase47), although there were some methodological concerns. For example, with QAlb = 50(×10−3), if Q Mean and Q Lim3SD are, respectively, 31.1 and 44.8, then Q IgG is still below Q Lim although a true ITS occurs up to IgGLoc = 100 mg/L (QIgG = 41.2). In this situation, OCB would be blurred and a smaller ITS would be completely silent. Moreover, some of the control patients used to calculate Reiber's formula were GBS patients, thereby introducing a potential self‐referencing bias. As a conclusion, the possibility of a small ITS associated with GBS should be reconsidered.

A major and unexpected result of QAlb variations is the paradoxical increase in IgG index and IgGLoc(Lim) in the absence of a real change in ITS. This pitfall is avoided by calculating IgGLoc(mean), which remains unchanged. However, it only concerns cases in which the level of ITS is low.

Since ITS may be a surrogate marker of a persistent intrathecal inflammation or be pathogenic by itself, any change in level may be a valuable target for future therapies.48 Although slight changes may be difficult to demonstrate, we calculated that the size of the cohort required to demonstrate a decrease in ITS may be adjusted to the expected proportion of higher QAlb.

Conclusion

We herein demonstrate and quantify for the first time the range of underestimation of intrathecal IgG synthesis in individual patients. This range is higher than the lower common range of IgG concentrations required to obtain a biological effect. On the other hand, results obtained with cohorts fit well with the exact ITS value. Importantly, the sample size of a cohort needed to demonstrate slight variations in ITS requires adjustment with the expected BCB permeability.

Author Contributions

BM conceptualized and designed the study; BM and GGM collected the clinical data. GGM and CH collected and managed the biological data. BM, BB, EK, MR, DH and DS clinically managed the data. BM, GGM, DH and DS analyzed and interpreted the data. BM, DH and DS performed the statistical analysis. BM drafted the manuscript; all authors critically evaluated the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Nothing to report.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to R. Cooke for copyediting.

References

- 1. Felgenhauer K. Protein size and cerebrospinal fluid composition. Klin Wochenschr 1974;52:1158–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reiber H. Dynamics of brain‐derived proteins in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Chim Acta 2001;310:173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Granata T, Gobbi G, Spreafico R, et al. Rasmussen's encephalitis: early characteristics allow diagnosis. Neurology 2003;60:422–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doyle KP, Quach LN, Sole M, et al. B‐lymphocyte‐mediated delayed cognitive impairment following stroke. J Neurosci 2015;35:2133–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta PD, Patrick BA, Mehta SP, Wisniewski HM. Chronic relapsing EAE in guinea pigs: IgG index and oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid and sera. Immunol Invest 1985;14:347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olsson T, Henriksson A, Link H, Kristensson K. IgM and IgG responses during chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (r‐EAE). J Neuroimmunol 1984;6:265–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suckling AJ, Reiber H, Kirby JA, Rumsby MG. Chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Immunological and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier‐dependent changes in the cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroimmunol 1983;4:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Link H, Tibbling G. Principles of albumin and IgG analyses in neurological disorders. III. Evaluation of IgG synthesis within the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1977;37:397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reiber H, Teut M, Pohl D, et al. Paediatric and adult multiple sclerosis: age‐related differences and time course of the neuroimmunological response in cerebrospinal fluid. Mult Scler 2009;15:1466–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reiber H, Felgenhauer K. Protein transfer at the blood cerebrospinal fluid barrier and the quantitation of the humoral immune response within the central nervous system. Clin Chim Acta 1987;163:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reiber H. Flow rate of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)–a concept common to normal blood‐CSF barrier function and to dysfunction in neurological diseases. J Neurol Sci 1994;122:189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reiber H. Knowledge‐base for interpretation of cerebrospinal fluid data patterns. Essentials in neurology and psychiatry. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2016;74:501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reiber H. Cerebrospinal fluid data compilation and knowledge‐based interpretation of bacterial, viral, parasitic, oncological, chronic inflammatory and demyelinating diseases. Diagnostic patterns not to be missed in neurology and psychiatry. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2016;74:337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dalakas MC, Li M, Fujii M, Jacobowitz DM. Stiff person syndrome: quantification, specificity, and intrathecal synthesis of GAD65 antibodies. Neurology 2001;57:780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reiber H. Cerebrospinal fluid–physiology, analysis and interpretation of protein patterns for diagnosis of neurological diseases. Mult Scler 1998;4:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blennow K, Fredman P, Wallin A, et al. Formulas for the quantitation of intrathecal IgG production. Their validity in the presence of blood‐brain barrier damage and their utility in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1994;121:90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Auer M, Hegen H, Zeileis A, Deisenhammer F. Quantitation of intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis ‐ a new empirical formula. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uher T, Horakova D, Tyblova M, et al. Increased albumin quotient (QAlb) in patients after first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis is associated with development of brain atrophy and greater disability 48 months later. Mult Scler 2016;22:770–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akaishi T, Narikawa K, Suzuki Y, et al. Importance of the quotient of albumin, quotient of immunoglobulin G and Reibergram in inflammatory neurological disorders with disease‐specific patterns of blood–brain barrier permeability. Neurol Clin Neurosci 2015;3:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ratzer R, Iversen P, Bornsen L, et al. Monthly oral methylprednisolone pulse treatment in progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016;22:926–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kowarik MC, Pellkofer HL, Cepok S, et al. Differential effects of fingolimod (FTY720) on immune cells in the CSF and blood of patients with MS. Neurology 2011;76:1214–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mancuso R, Franciotta D, Rovaris M, et al. Effects of natalizumab on oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients: a longitudinal study. Mult Scler 2014;20:1900–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frequin ST, Barkhof F, Lamers KJ, et al. CSF myelin basic protein, IgG and IgM levels in 101 MS patients before and after treatment with high‐dose intravenous methylprednisolone. Acta Neurol Scand 1992;86:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang HY, Matsui M, Araya S, et al. Immune parameters associated with early treatment effects of high‐dose intravenous methylprednisolone in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2003;216:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Glehn F, Farias AS, de Oliveira AC, et al. Disappearance of cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands after natalizumab treatment of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2012;18:1038–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrer A, Tumani H, Niendorf S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid parameters of B cell‐related activity in patients with active disease during natalizumab therapy. Mult Scler 2013;19:1209–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Romme Christensen J, Ratzer R, Bornsen L, et al. Natalizumab in progressive MS: results of an open‐label, phase 2A, proof‐of‐concept trial. Neurology 2014;82:1499–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Axelsson M, Mattsson N, Malmestrom C, et al. The influence of disease duration, clinical course, and immunosuppressive therapy on the synthesis of intrathecal oligoclonal IgG bands in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2013;264:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. von Budingen HC, Harrer MD, Kuenzle S, et al. Clonally expanded plasma cells in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients produce myelin‐specific antibodies. Eur J Immunol 2008;38:2014–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Castillo‐Gomez E, Kastner A, Steiner J, et al. The brain as ‘immunoprecipitator’ of serum autoantibodies against NMDAR1. Ann Neurol 2016;79:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O'Connor KC, Appel H, Bregoli L, et al. Antibodies from inflamed central nervous system tissue recognize myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Immunol 2005;175:1974–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Graus F, Abos J, Roquer J, et al. Effect of plasmapheresis on serum and CSF autoantibody levels in CNS paraneoplastic syndromes. Neurology 1990;40:1621–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Furneaux HF, Reich L, Posner JB. Autoantibody synthesis in the central nervous system of patients with paraneoplastic syndromes. Neurology 1990;40:1085–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Warnke C, Stettner M, Lehmensiek V, et al. Natalizumab exerts a suppressive effect on surrogates of B cell function in blood and CSF. Mult Scler 2015;21:1036–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Warnke C, von Geldern G, Markwerth P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid JC virus antibody index for diagnosis of natalizumab‐associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 2014;76:792–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piepgras J, Holtje M, Otto C, et al. Intrathecal immunoglobulin A and G antibodies to synapsin in a patient with limbic encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015; 2: e169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kadoch C, Li J, Wong VS, et al. Complement activation and intraventricular rituximab distribution in recurrent central nervous system lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1029–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chopek M, Mc Cullough J. Protein and biochemical changes during plasma exchange In: Berkman E, Umlas J, eds. Therapeutic Hemapheresis. Washington, DC: AABB Press, 1980:13–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brecher ME. Plasma exchange: why we do what we do. J Clin Apheresis 2002;17:207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berger B, Hottenrott T, Leubner J, et al. Transient spurious intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in neurological patients after therapeutic apheresis. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Madzar D, Maihofner C, Zimmermann R, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid under non‐steady state condition caused by plasmapheresis. J Neural Transm 2011;118:219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reiber H. Polyspecific antibodies without persisting antigen in multiple sclerosis, neurolupus and Guillain‐Barré syndrome: immune network connectivity in chronic diseases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2017;75:580–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zeman A, McLean B, Keir G, et al. The significance of serum oligoclonal bands in neurological diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993;56:32–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wanschitz J, Ehling R, Loscher WN, et al. Intrathecal anti‐alphaB‐crystallin IgG antibody responses: potential inflammatory markers in Guillain‐Barre syndrome. J Neurol 2008;255:917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mata S, Galli E, Amantini A, et al. Anti‐ganglioside antibodies and elevated CSF IgG levels in Guillain‐Barre syndrome. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Simone IL, Annunziata P, Maimone D, et al. Serum and CSF anti‐GM1 antibodies in patients with Guillain‐Barre syndrome and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J Neurol Sci 1993;114:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Meyer Sauteur PM, Huizinga R, Tio‐Gillen AP, et al. Intrathecal antibody responses to GalC in Guillain‐Barre syndrome triggered by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Neuroimmunol 2018;314:13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bonnan M. Intrathecal IgG synthesis: a resistant and valuable target for future multiple sclerosis treatments. Mult Scler Int 2014;2015:296184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]