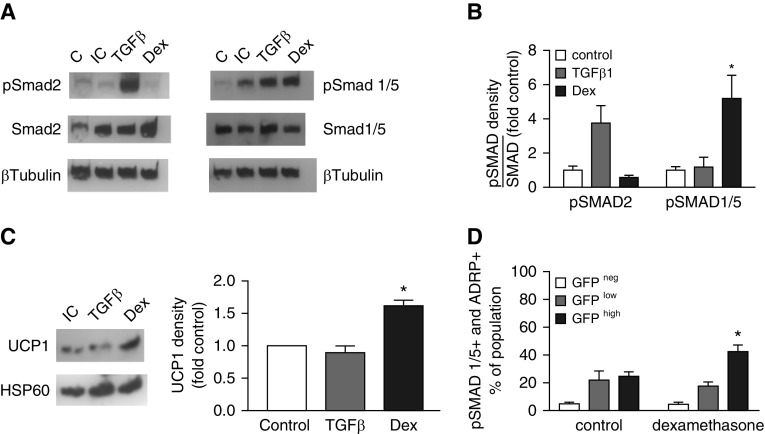

Figure 6.

Dex increases UCP1 in cultured MLg 2908 cells and pSMAD1/5 both in culture and in vivo. (A) MLg 2908 neonatal mouse lung fibroblasts were induced to assume a lipid-storage phenotype and then exposed to medium alone (control) or supplemented with either transforming growth factor β 1 (TGF-β1) or Dex and then harvested for Western immunoblotting. The blots were probed for either pSmad2 and Smad2 or pSmad1/5 and Smad1/5, followed by β-tubulin. C, uninduced control; IC, induced control. (B) The density of pSmads in immunoblots is expressed relative to the abundance of the corresponding Smad for each sample and normalized to the ratio for the control. Mean ± SEM, n = 4 separate experiments, *P < 0.05 comparing Smad1/5 for Dex-treated MLg with controls. (C) MLg cells were induced and stimulated as in A before mitochondrial isolation and Western immunoblotting. The density of UCP1 relative to the respective induced control (set to a density of one) is shown for three separate experiments. Mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 comparing Dex-treated mice with controls. (D) On P8, fibroblasts were isolated from a separate cohort of controls or mice that had been treated with Dex as shown in Fig. 1A. (A) After staining for pSmad1/5 and ADRP, flow cytometry was performed, gating on CD45− cells. Mean ± SEM, n = 5 mice for each treatment group from four different litters. *P < 0.05 comparing the GFPhigh population from Dex-treated mice with controls. HSP60, heat shock protein 60; pSMAD, phosphorylated form of a homolog of the Drosophila family of proteins including SMA (small body size) and mothers against decapentaplegia (MAD).