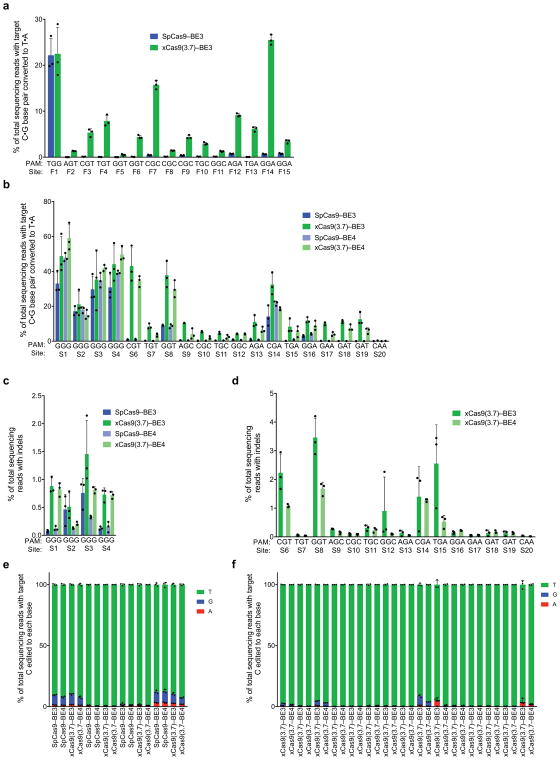

Extended Data Figure 9. Cytidine base editing at 15 additional genomic sites and xCas9 base editing with the BE4 architecture.

a, Base editing by SpCas9–BE3 and xCas9(3.7)–BE3 at 15 sites within the FANCF gene in HEK293T cells. The C•G to T•A conversion frequency at the most efficiently edited base 3 days after plasmid transfection is shown. b, Test of xCas9 3.7 in the BE4 architecture34 on the same sites tested in Fig. 3. The C•G to T•A conversion frequency in HEK293T cells at the most efficiently edited base 3 days after plasmid transfection is shown. c, d, Indel frequency following treatment with BE3 or BE4 variants targeting sites with NGG PAMs (c) and non-NGG PAMs (d). e, f, Product distribution among edited DNA sequence reads (reads in which the target C is mutated) following treatment with BE3 or BE4 variants targeting sites with NGG PAMs (e) and non-NGG PAMs (f). Since SpCas9 has minimal activity on non-NGG PAM sites, only xCas9(3.7)–BE3 and xCas9(3.7)–BE4 data is compared on non-NGG PAM sites. Values and error bars reflect the mean and s.d. of n=3 biologically independent samples. Target sites are in Supplementary Table 12.