Abstract

Indonesia’s peatlands experience frequent and intense wildfires, producing hazardous smoke with consequences for human health, yet there is a lack of research into adverse effects on wildlife. We evaluated the effects of smoke on the activity and energy balance of Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) in a peat swamp forest at the Tuanan Research Station, Central Kalimantan. We collected behavioural data and urine samples from four adult flanged males before, during, and after wildfires between March 2015 and January 2016. During fires, particulate matter (PM10) concentrations were hazardous. Orangutans increased rest time during and after the smoke period, and decreased travel time and distance and increased fat catabolism post-smoke. The increase in post-smoke ketones was not related to changes in caloric intake and was likely due to an increase in energy expenditure, possibly related to immune response. Results show that wildfire smoke negatively affects orangutan condition, and sustained research is needed to assess the magnitude of the threat to the long-term viability of this Critically Endangered species.

Introduction

Wildfires have occurred in Southeast Asia for millennia, but are increasingly frequent and intense, with the most extensive fires in Indonesia’s peatlands1. Peat fires are a perfect storm resulting from a combination of human activities during recent decades that have dramatically altered these ecosystems via deforestation and draining for conversion to agricultural lands2. Repeated burnings have made these landscapes more susceptible to fires, exacerbated by drought conditions produced by strong El Niño weather systems3. Peatland fires not only destroy thousands of hectares of forest annually, but also release tons of carbon and other gases, contributing to global climate change, and producing hazardous air pollution4. The most disastrous of Indonesia’s fires occurred in 1997 and contributed the equivalent of as much as 40% of the average annual global carbon emissions from the burning of fossil fuels3.

In addition to greenhouse gases, wildfire smoke contains numerous hazardous components, including particulate matter (PM), the leading cause of worldwide pollution-related mortality, and carbon monoxide (CO), a poisonous gas that reduces the amount of oxygen transported to critical organs, including the heart and brain4. In 2015, Indonesia’s peat fires exhibited the most severe fire activity and smoke pollution recorded since NASA’s Earth Observing satellite system began observations in the early 2000s5. The widespread haze produced from these peat fires had significant impacts on human health, causing an estimated 100,300 deaths in the aftermath of the fire6. Most of these deaths likely occurred over the course of the first year after the fire (Loretta Mickley, personal communication).

Wildfire smoke appears to affect the health of nonhuman animals as well, causing eye and throat irritation, breathing difficulty, and impaired immune function in livestock animals like sheep and horses7. Furthermore, a study of Bornean gibbons (Hylobates albibarbis) during the 2006 peat fires found that individuals sang fewer and shorter songs on smoky days8. Given the consequences of haze for human health, these behavioural changes could indicate underlying health effects, though we are not aware of any studies documenting adverse health effects from forest fire smoke for wildlife.

Borneo’s peatlands contain a large proportion of the island’s fauna and provide critical habitats for many threatened species, including the Critically Endangered Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)9,10. Peat-dwelling orangutans are ideal models to investigate how smoke affects wildlife health, as they are an indicator species whose health and behaviour signal environmental quality11. For instance, when fruit is scarce, Bornean orangutans conserve energy by decreasing their active period, travel time, and travel distance, and metabolize fat reserves to produce energy12–15, and in disturbed habitats, travel shorter distances and spend more time resting16,17.

There is a paucity of research into the behavioural changes of animals surviving wildfires, with a noteworthy exception: antechinus (Antechinus stuartii), small insectivorous marsupials, decrease daytime activity and increase energy-conserving torpor use following both prescribed fires and wildfires in Australia. These shifts are thought to be key to individuals’ survival by reducing their energy requirements in burnt areas where food resources are severely reduced, and have been proposed to provide a competitive edge to heterothermic mammals that are able to adjust their energy requirements18,19. While this research provides fascinating insights into the behavioural responses of small insectivorous mammals in burned habitats, no studies have documented similar energy conservation strategies by animals in unburned areas in response to smoke exposure.

Indonesia’s 2015 peat fires provided a unique opportunity to document, for the first time, changes in orangutan behaviour and health in response to wildfire smoke. As a leading cause of haze and the air pollutant most strongly linked to adverse health effects in humans – including asthma, heart attack, and early death20 – we predicted that high particulate matter (PM10) would negatively impact orangutan energetic condition, reflected in reduced travel times, active periods, and travel distances, and increased resting times and ketosis.

Methods

Study Site and Subjects

We conducted research at the Tuanan Orangutan Research Station situated within a 105,166 ha protected area (KPHL Model Kapuas) in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia (2°09′06.1′′S; 114°26′26.3′′E, Fig. 1). Tuanan lies within the Ex-Mega Rice Project, a million-hectare agricultural land conversion project implemented in 1996–1997 that resulted in the construction of more than 4,500 km of drainage and irrigation channels. As a result, more than half of this area burned during the El Niño-driven wildfires of 1997–1998, contributing to a loss of 72% of peat swamp forests in the following nine years and leaving much of the peatland deeply degraded4,21. The study area comprises approximately 900 hectares of regenerating peat swamp forest, about 10% of which burned in 2015. Although Tuanan exhibits less pronounced fluctuations compared to the dipterocarp-dominated masting forests of Borneo, the availability of fruit demonstrates strong inter-annual variation in the magnitude and timing of peak-fruit periods22.

Figure 1.

Map depicting 2015 fire hotspots (grey triangles) across Central Kalimantan detected by satellite (MODIS Active Fire Detections data set), and those within 10 km of Tuanan (TRS) and Palangkaraya (PKY) study locations (black triangles). Map created using ESRI® ArcMapTM 9.3 http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis/eval-help/arcgis-93.

Data were collected between March 2015 and January 2016 as part of a long-term investigation into flanged male orangutan energetics initiated in 2013. We divided the data into three periods: pre-smoke (March–July 2015), smoke (September–October 2015), and post-smoke (November 2015–January 2016). These periods were delineated by the smoke conditions at the research station, recorded daily as the presence or absence of visible smoke by research station staff. WME, EJB, ANH, and local research assistants conducted full-day observations of four habituated adult flanged males across the three study periods (pre-smoke: N = 18 days, mean = 4.5 days/male; smoke N = 20 days, mean = 5 days/male; post-smoke N = 16 days, mean = 4 days/male; Supplementary Table S1).

Data and Sample Collection

We collected behavioural data during nest-to-nest focal animal follows, using two-minute instantaneous sampling to record activity and feeding23. We defined active period as the duration from the first activity point after the focal animal left the nest in the morning until the first activity point when the focal was resting in its nest for the evening. Rest time and travel time were calculated as the proportion of instantaneous samples during the active period when the focal animal was resting or travelling, respectively24. For feeding bouts, we recorded the species, part, and ripeness of food items; calculated energy intake per feeding bout using item-specific feeding rates and nutritional content; and summed all feeding bouts to estimate daily caloric intake (following the nutritional methods and energetic calculations reported in15,22). Ranging data were collected using a handheld GPS unit (Garmin GPSMap 62s), which we used to record the location of the focal animal at 10-minute intervals, and we calculated daily path lengths using the HoRAE toolbox in OpenJUMP25.

To determine whether animals were in ketosis, we collected urine samples opportunistically, prioritising the first urination each morning (modal collection time = 05:00). Samples were collected by positioning a plastic bag under the urinating animal, or by immediately pipetting urine from the leaves or ground. We did not collect samples contaminated with faeces, and used Chemstrip® Test Strips (10 SG or UA, Roche Diagnostics USA) to test for ketones as soon as possible (mean elapsed time = 6.1 minutes).

To document ecological habitat changes, we monitored all of the trees in three phenological plots containing ~1,650 tagged trees (diameter at breast height >10 cm) covering 2.3 ha. We calculated the monthly fruit availability index (FAI) as the number of trees bearing fruits divided by the total number of trees sampled15,26.

We acquired archived data on fire hotspots in Central Kalimantan from the NASA Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) MODIS active fire data set27. Air quality was assessed via concentrations of particulate matter (PM10), collected daily by the BMKG (Meteorology, Climatology & Geophysics Council) in Palangkaraya, located approximately 55 km west of Tuanan. In accordance with the Clean Air Act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency strictly regulates this pollutant, and PM10 values exceeding 150 µg/m3 in a 24-hour period are considered harmful to public health and the environment. Using the NASA FIRMS MODIS active fire data set, we quantified the number of fire hotspots within a 10-km radius of the research station as well as Palangkaraya, where the air quality data were collected.

Data Analysis

For each dependent variable (daily travel time, rest time, active period, travel distance, ketones presence, and caloric intake), we used general linear mixed models (LMM) to determine: 1) immediate effects, i.e., those observed during the smoke period (pre-smoke vs. smoke) and 2) persistent effects, i.e., those observed after the smoke period (pre-smoke vs. post-smoke), including individual ID as a random effect and fruit availability (FAI) as a covariate. We conducted diagnostic tests of all models (residual distribution, leverage, and influence)28. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 13 (Dell Inc., Tulsa, OK). We used two-tailed tests, set alpha at 0.05, and corrected for multiple comparisons against the pre-smoke dataset following29.

Ethical Approval

Research permits were issued by RISTEK-DIKTI (Permit #137/SIP/FRP/SM/V/2013) following the legal requirements of conducting research in Indonesia, and all research methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Rutgers University (Protocol #11-030).

Data Availability Statement

All biological data analysed for this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file. The air quality data that support the findings of this study are available from BMKG (Meteorology, Climatology & Geophysics Council) in Palangkaraya but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of BMKG Palangkaraya.

Results

Fire Activity and Air Quality

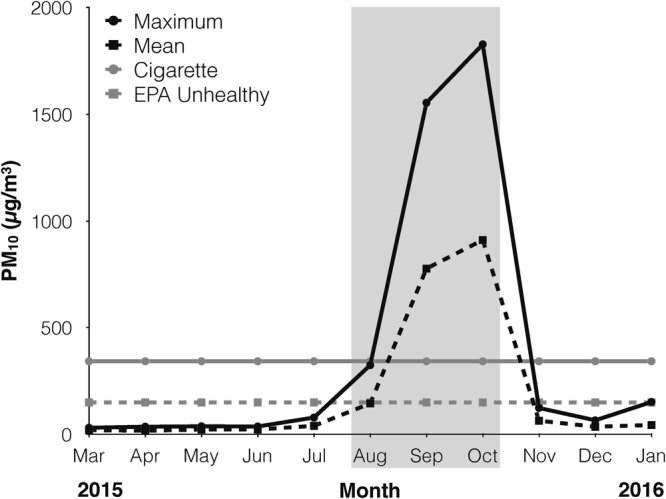

Smoke conditions were recorded daily at the Tuanan Research station. We observed smoke from nearby forest fires beginning August 7 through November 6, 2015 (hereafter, fire season), when daily rains marked the arrival of the wet season. During the 2015 fire season, 79% of daily PM10 values recorded in Palangkaraya exceeded unhealthy levels (63 of 80 days sampled; mean = 588.0, range 61–1,829 µg/m3). In October, mean and maximum monthly values exceeded unhealthy levels by more than 6 and 12 times, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Maximum (solid black) and mean (dashed black) monthly PM10 values observed in Palangkaraya across the study period. PM10 after lighting a cigarette (solid grey)38 and the EPA unhealthy limit (dashed grey) for reference. Light grey rectangle indicates the smoke period.

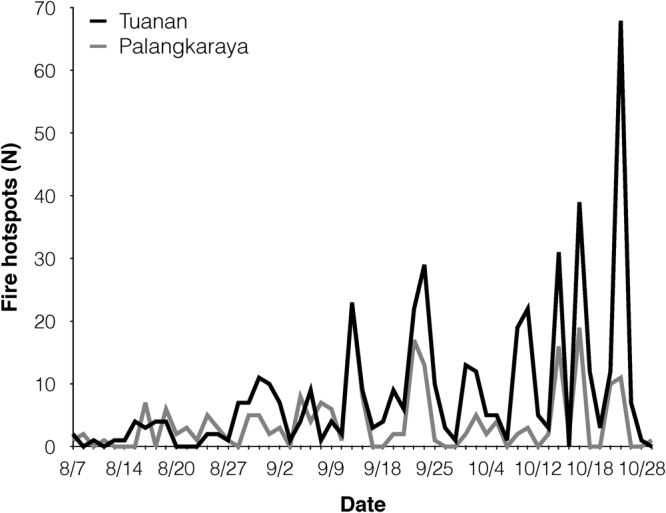

During the fire season, a total of 218 fire hotspots (200 occurring on peatlands) were detected within 10 km of Palangkaraya (Fig. 3). At the same time, 465 hotspots (434 occurring on peatlands) were detected within 10 km of Tuanan (Fig. 3). Outside of the fire season, only eight hotspots (N = 7 pre-smoke, N = 1 post-smoke) were detected in Palangkara and five hotspots in Tuanan (pre-smoke only) in 2015. Daily fire activity at Tuanan (mean = 5.3, range 0–68 hotspots) was significantly greater than in Palangkaraya (mean = 2.5, range 0–23 hotspots; t = 3.45, p < 0.001) across the fire season.

Figure 3.

Daily fire hotspots detected by satellites (MODIS Active Fire Detections data set) at Tuanan (black) and Palangkaraya (grey) during the fire season.

We compared air quality across the three study periods during which we collected behavioural and ecological data at Tuanan (Pre-smoke: March 15–July 7, Smoke: September 4–October 17, Post-Smoke: November 19–January 13). Average daily air quality varied significantly across periods (F2,149 = 353.2, p < 0.0001). Pre- and post-smoke periods did not differ from each other (mean: pre-smoke = 22.2, post-smoke = 42.6 µg/m3; Tukey HSD: p = 0.77), but both had lower PM10 compared to the smoke period (mean: smoke = 830.2 µg/m3; Tukey HSD: p < 0.0001).

Orangutan Activity and Energy Balance

We examined the immediate effects of smoke on orangutan behaviour by comparing data collected during the pre-smoke and smoke periods. Rest time increased significantly during the smoke period compared to baseline levels (Table 1a, Fig. 4a). Neither travel time, active period, nor travel distance significantly differed across these periods (Table 1a, Fig. 4b–d).

Table 1.

LMM results for (a) immediate (smoke) and (b) persistent (post-smoke) changes in activity and energetics; italics = significant after Hochberg correction.

| (a) Immediate | FAI | ID | Smoke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | F | p | F | p | F | p |

| Rest time | 0.38 | 0.006 | 0.94 | 0.434 | 20.10 | <0.001 |

| Travel time | 3.92 | 0.056 | 5.48 | 0.004 | 0.65 | 0.428 |

| Travel distance | 0.97 | 0.333 | 0.321 | 0.810 | 0.06 | 0.812 |

| Active period | 0.09 | 0.762 | 6.07 | 0.002 | 0.16 | 0.691 |

| Calorie intake | 0.33 | 0.568 | 3.69 | 0.022 | 0.17 | 0.679 |

| Ketones | 6.85 | 0.014 | 7.99 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.466 |

| (b) Persistent | FAI | ID | Post-Smoke | |||

| Rest time | 13.76 | 0.001 | 9.79 | <0.001 | 10.92 | 0.003 |

| Travel time | 0.08 | 0.774 | 13.14 | <0.001 | 16.75 | <0.001 |

| Travel distance | 0.00 | 0.977 | 1.20 | 0.327 | 10.92 | 0.003 |

| Active period | 0.88 | 0.356 | 10.15 | <0.001 | 4.26 | 0.048 |

| Calorie intake | 0.96 | 0.336 | 15.92 | <0.001 | 84.18 | 0.001 |

| Ketones | 0.87 | 0.359 | 0.77 | 0.520 | 7.69 | <0.011 |

Figure 4.

Box plots depicting orangutan activity and energetics across the three study periods (a = rest time, b = travel time, c = travel distance, d = active period, e = caloric intake, f = ketones).

We tested for possible persistent effects of smoke by comparing data collected during pre-smoke and post-smoke periods. As predicted, rest time increased and travel time and travel distance decreased (Table 1b, Fig. 4a–c). Following correction for multiple comparisons, active period did not change during the post-smoke period.

We analysed 60 urine samples for the presence of ketones across the three study periods (pre-smoke = 19, smoke = 24, post-smoke = 17 samples). Neither the proportion of samples with ketones nor energy intake differed between pre-smoke and smoke periods (Table 1, Fig. 4e,f). In contrast, both the proportion of samples with ketones and energy intake showed significant increases during the post-smoke period, indicating that the increase in ketone production was not due to reduced calorie consumption (Table 1, Fig. 4e,f). Although fruit availability reached its lowest in May, and was significantly lower during the pre-smoke period compared to the post-smoke period (pre-smoke average = 2.82, minimum = 1.95; post-smoke average = 3.26, minimum = 2.37; t = 19.6, p < 0.001), ketones were not detected during the pre-smoke period (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Urine samples testing positive for ketones (bars) in relation to fruit availability (line) across the study period. Monthly sample sizes are indicated on the x-axis. Light grey rectangle indicates the smoke period.

Discussion

Our study provides the first evidence that wildfire smoke affects orangutan condition. Orangutans reduced their energy budgets by resting more during and after smoke, and spent less time travelling shorter distances while experiencing negative energy balance post-smoke. These changes are similar to those observed during periods of fruit scarcity, when Bornean orangutans adopt an energy-conserving strategy12,15. In the Tuanan population, in particular, orangutans have been observed to fall into a negative energy balance state, as evidenced by significantly higher levels of ketone production, during periods of low fruit availability when energy intake is lowest30. As ketones indicate animals are catabolizing fat as an energy source, it appears orangutans in this study had entered a state of negative energy balance, expending more energy than they consumed post-smoke. Despite lower fruit availability and calorie consumption pre-smoke, no ketones were detected during that period, indicating that post-smoke ketosis was not merely due to reduced energy intake. It is thus more likely that orangutans had increased their energy expenditure post-smoke, despite energy-conserving behavioural changes in physical activity, namely resting and travelling. Such an increase in energy expenditure could occur if animals were experiencing allostatic load, for instance, through increased stress hormone production or immune response31. Interestingly, human subjects exposed to high PM10 levels during the 1997 forest fires showed elevated circulating cytokines (proinflammatory signalling proteins: IL-1β, IL-6, and GM-CSF), indicating a systemic inflammatory response, likely due to the adverse cardiopulmonary effects of particulate air pollution32. As systemic inflammatory responses can elevate energy expenditure and cause weight loss in humans33, increased inflammation presents a possible mechanism for the ketosis we observed post-smoke, and future studies should explore changes in cytokines and other relevant biomarkers (e.g., neopterin, cortisol) in response to wildfire smoke.

Overall, most of our predictions were supported, though our study design and the small number of individuals sampled limit our conclusions. Although for most variables, significant changes were only detected post-smoke, we cannot conclude that orangutans did not experience any health consequences during the fire season and are unable to identify the timing of potential adverse effects. Unfortunately, we were unable to collect data during the peak smoke period (October 14–31), as orangutan observations were suspended for one month while the research team focused on fighting fires. As 173 fire hotspots were detected at Tuanan (37% of total) during the period of research suspension, it is entirely possible that health consequences emerged or intensified during that time. Furthermore, the air quality data we obtained from Palangkaraya is probably a conservative estimate of the conditions experienced by orangutans, as more than twice as many fire hotspots were detected at Tuanan than Palangkaraya across the entire fire season.

Nonetheless, our results suggest that smoke-exposure effects persist at least a few months, highlighting the potential for long-term impacts on wildlife populations. Our findings complement a recent study conducted in Singapore, where ecological community acoustic activity was significantly reduced during the 2015 haze produced by Indonesia’s peatland fires, exhibiting only partial recovery 16 weeks after the smoke had dissipated34. The impacts on wildlife inhabiting Borneo, where air pollution was 15 times worse than that in Singapore, are likely to be much more severe and could be longer-lasting34.

Peatland habitats are integral to the survival of the Critically Endangered Bornean orangutan, whose largest populations inhabit the peat swamp forests of Central Kalimantan9. Annual fires in Borneo significantly impact orangutan habitats and populations, burning > 20,000 km2 of forest and killing hundreds of orangutans in 2015 alone35. Whereas the direct impacts from wildfires are relatively clear, we have little understanding of the indirect effects on surviving wildlife in unburned areas. The unexpected loss of an estimated 93,000 Bornean orangutans from intact forests in Kalimantan between 1999 and 2015 indicates that drivers independent of land-use change are contributing to their population declines36. Prolonged and repeated exposure to toxic smoke may have severe health consequences for orangutans and other wildlife, highlighting the urgent need for sustained research into the long-term impacts. Future studies should include non-adults, especially developing foetuses and infants who are likely to be most vulnerable to long-term health effects37. We plan to expand this research by including additional physiological indicators of health, which will further elucidate the short- and long-term impacts of wildfire smoke on orangutan health and conservation.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are incredibly grateful to the Tuanan Orangutan Research Project team, including our fantastic research assistants (Abuk, Idun, Isman, Rahmadt, Suga, Suwi, Tono), together with the other members of the heroic fire-fighting team (Upa, Nato, Jambran, Barudin, Anyan, Cahaya, Ino, Becca, Julia, Carson, Alex), and camp managers (Perry, Misdi). We offer special thanks to partners Jito Sugardjito and Tatang Mitra Setia and founders and directors Maria van Noordwijk and Carel van Schaik, as well as previous researchers Lynda Dunkel and Brigitte Spillmann for their habituation efforts. This project would not have been possible without funding from Rutgers University and USAID (No. AID-497-A-13-00005); as well as permits, agreements and support from Indonesian partners including Universitas Nasional, RISTEK-DIKTI, BKSDA, LIPI, KLHK, and the BOS Foundation. We thank the helpful staff at the Palangkaraya BMKG for air quality data and Didik Prasetyo for his help in facilitating this data sharing.

Author Contributions

W.E. designed study, collected and analysed data, and wrote the paper. E.B. and A.H. collected data. S.A. helped to coordinate research. E.V. collected and analysed FAI and nutrition data, contributed to figure preparation, facilitated research, and provided funding. All authors edited and provided comments on the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25847-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Page, S. et al. Tropical peatland fires in Southeast Asia in Tropical fire ecology: climate change, land use, and ecosystem dynamics (eds Cochrane, M. A.) 263–287 (Springer, 2009).

- 2.Gaveau DL, et al. Major atmospheric emissions from peat fires in Southeast Asia during non-drought years: evidence from the 2013 Sumatran fires. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6112. doi: 10.1038/srep06112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page SE, et al. The amount of carbon released from peat and forest fires in Indonesia during 1997. Nature. 2002;420:61–65. doi: 10.1038/nature01131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page SE, Hooijer A. In the line of fire: the peatlands of Southeast Asia. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2016;371:20150176. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field RD, et al. Indonesian fire activity and smoke pollution in 2015 show persistent nonlinear sensitivity to El Niño-induced drought. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:9204–9209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524888113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koplitz SN, et al. Public health impacts of the severe haze in Equatorial Asia in September-October 2015: demonstration of a new framework for informing fire management strategies to reduce downwind smoke exposure. Environ Res Lett. 2016;11:094023. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/9/094023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh PS. Fire and smoke inhalation injury in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2007;23:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cveq.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheyne SM. Effects of meteorology, astronomical variables, location and human disturbance on the singing apes: Hylobates albibarbis. Am J Primatol. 2008;70:386–392. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrogh-Bernard H, Husson S, Page SE, Rieley JO. Population status of the Bornean orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus) in the Sebangau peat swamp forest, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biol Conserv. 2003;110:141–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00186-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Posa MRC, Wijedasa LS, Corlett RT. Biodiversity and conservation of tropical peat swamp forests. BioScience. 2011;61:49–57. doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.1.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison, M. E., Cheyne, S. M., Morrogh-Bernard, H. & Husson, S. J. What can apes tell us about the health of their environment? A review of the use of orang-utans and gibbons as indicators of changes in habitat quality in tropical peat swamp forests. Proceedings of the International Symposium and Workshop on Restoration and Wise Use of Tropical Peatland, Palangka Raya, Indonesia 104–107 (2005).

- 12.Knott CD. Changes in orangutan caloric intake, energy balance, and ketones in response to fluctuating fruit availability. Int J Primatol. 1998;19:1061–1079. doi: 10.1023/A:1020330404983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrogh-Bernard, H. C. et al. Orangutan activity budgets and diet: a comparison between species, populations, and habitats in Orangutans: geographic variation in behavioral ecology and conservation 119–134 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- 14.Harrison ME, Morrogh-Bernard HC, Chivers DJ. Orangutan energetics and the influence of fruit availability in the nonmasting peat-swamp forest of Sabangau, Indonesian Borneo. Int J Primatol. 2010;31:585–607. doi: 10.1007/s10764-010-9415-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel ER, et al. Nutritional ecology of wild Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) in a peat swamp habitat: effects of age, sex, and season. Am J Primatol. 2017;79:1–20. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell-Smith G, Campbell-Smith M, Singleton I, Linkie M. Raiders of the lost bark: orangutan foraging strategies in a degraded landscape. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell-Smith G, Campbell-Smith M, Singleton I, Linkie M. Apes in space: saving an imperilled orangutan population in Sumatra. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stawski C, Körtner G, Nowack J, Geiser F. The importance of mammalian torpor for survival in a post-fire landscape. Biol Lett. 2015;11:20150134. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews JK, Stawski C, Körtner G, Parker CA, Geiser F. Torpor and basking after a severe wildfire: mammalian survival strategies in a scorched landscape. J Comp Physiol B. 2017;187:385–393. doi: 10.1007/s00360-016-1039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pope CA, III., Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manage. 2006;56:709–742. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoscilo A, Page SE, Tansey KJ, Rieley JO. Effect of repeated fires on land-cover change on peatland in southern Central Kalimantan, Indonesia, from 1973 to 2005. Int J Wildland Fire. 2011;20:578–588. doi: 10.1071/WF10029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel ER, et al. Nutritional differences between two orangutan habitats: implications for population density. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altmann J. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour. 1974;49:227–267. doi: 10.1163/156853974X00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McQueen A, et al. Bright birds are cautious: seasonally conspicuous plumage prompts risk avoidance by male superb fairy-wrens. Proc R Soc B. 2017;284:20170446. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiniger S, Hunter AJ. OpenJUMP HoRAE: a free GIS and toolbox for home-range analysis. Wildlife Soc B. 2012;36:600–608. doi: 10.1002/wsb.168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrangham RW, Conklin-Brittain NL, Hunt KD. Dietary response of chimpanzees and cercopithecines to seasonal variation in fruit abundance. I. Antifeedants. Int J Primatol. 1998;19:949–970. doi: 10.1023/A:1020318102257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NASA FIRMS “MODIS Active Fires.” Accessed through Global Forest Watch on [21 Dec 2017]. www.globalforestwatch.org (2017).

- 28.Quinn, G. P. & Keough, M. J. Experimental design and data analysis for biologists (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- 29.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel ER, et al. The power of protein: protein regulation, energetics, and health in wild Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017;162:29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muehlenbein MP, Hirschtick JL, Bonner JZ, Swartz AM. Toward quantifying the usage costs of human immunity: altered metabolic rates and hormone levels during acute immune activation in men. Am J Hum Biol. 2010;22:546–556. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Eeden SF, et al. Cytokines involved in the systemic inflammatory response induced by exposure to particulate matter air pollutants (PM10) Am J Resp Crit Care. 2001;164:826–830. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2010160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staal-van den Brekel AJ, Dentener MA, Schols AM, Buurman WA, Wouters EF. Increased resting energy expenditure and weight loss are related to a systemic inflammatory response in lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2600–2605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.10.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee BPYH, Davies ZG, Struebig MJ. Smoke pollution disrupted biodiversity during the 2015 El Niño fires in Southeast Asia. Environ Res Lett. 2017;12:094022. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa87ed. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ancrenaz, M. et al. Pongo pygmaeus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016e.T17975A17966347, http://c!x,doi.grgl1Q.23Q5/1UCN.lIK.2Q16-http://c!x,doi.1.RLTS.T11975Al1966341.en (2017).

- 36.Voigt M, et al. Global demand for natural resources eliminated more than 100,000 Bornean orangutans. Curr Biol. 2018;28:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Bell R, Pless-Mulloli T, Howel D. Does particulate air pollution contribute to infant death? A systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1365–1370. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Invernizzi G, et al. Particulate matter from tobacco versus diesel car exhaust: an educational perspective. Tob Control. 2004;13:219–221. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All biological data analysed for this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file. The air quality data that support the findings of this study are available from BMKG (Meteorology, Climatology & Geophysics Council) in Palangkaraya but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of BMKG Palangkaraya.