Abstract

Objective

To investigate the incidence of first-ever stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) and associated risk factors in a cohort of persons living with HIV infection (PLWH).

Design

Observational cohort study

Methods

We determined incidence rates of first-ever stroke/TIA in PLWH after ART initiation from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group ALLRT cohort and its parent trials. Poisson regression models evaluated baseline and time-varying covariates as risk factors for stroke/TIA.

Results

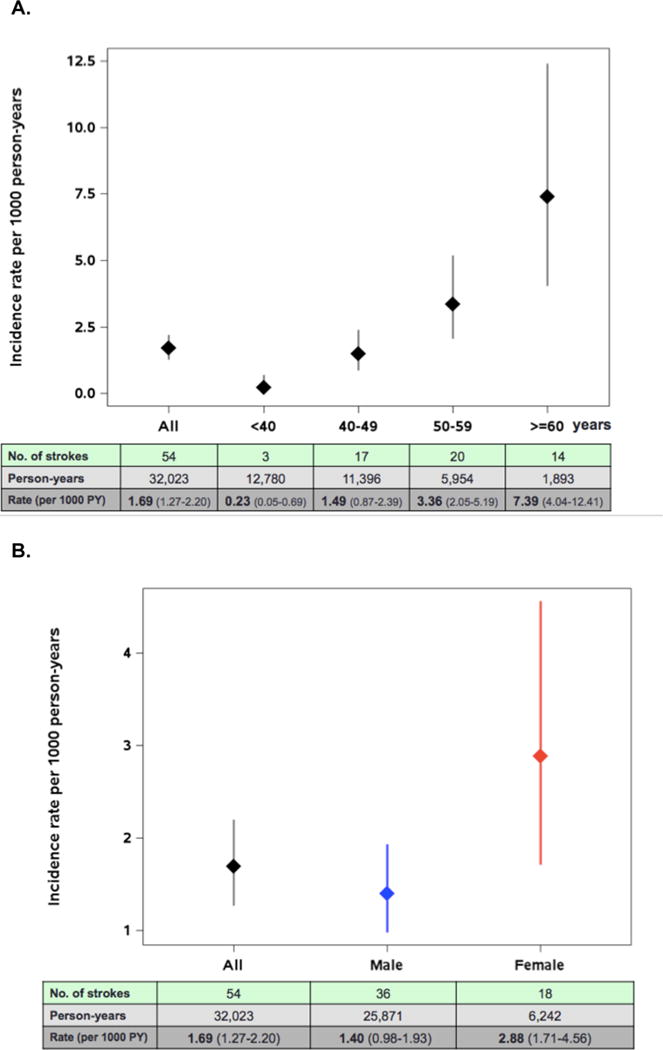

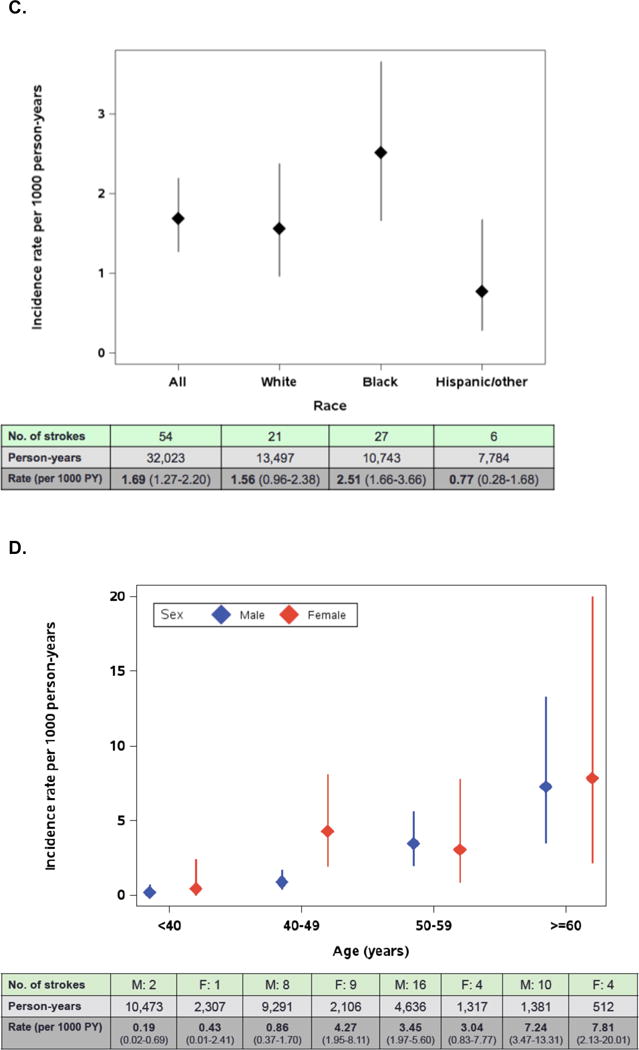

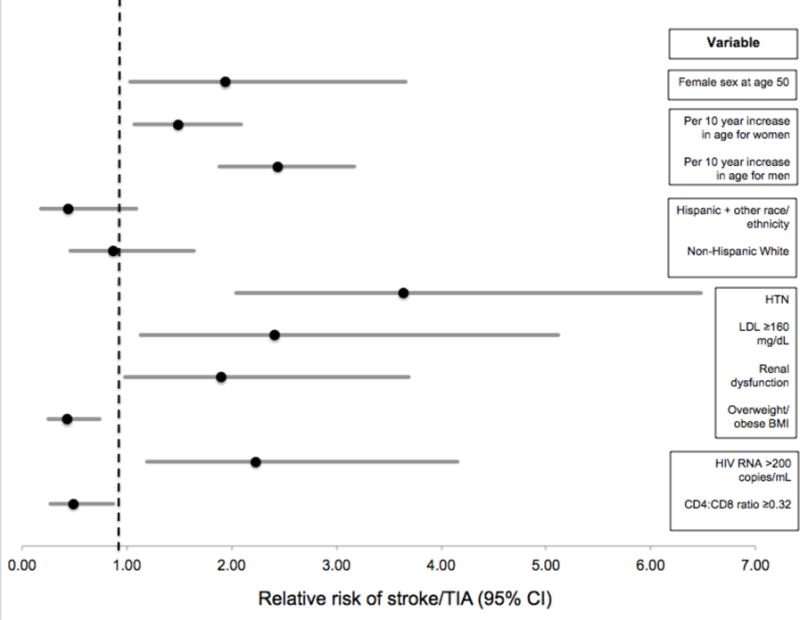

The incidence rate of stroke/TIA was 1.69 per 1000 person-years (PY). Incidence rates were highest in women (2.88 stroke/TIAs per 1000 PY compared with 1.40 per 1000 PY in men) and non-Hispanic Blacks (2.51 stroke/TIAs per 1000 PY compared with 0.77 per 1000 PY in Hispanic/other race/ethnicities and 1.56 per 1000 PY in Whites). In a multivariable model, we found a significant age-by-sex interaction (p=0.01). The higher risk of stroke/TIA in women was more pronounced at younger ages, while older age conferred a greater increase in stroke/TIA risk in men than women. Other risk factors for stroke/TIA included hypertension, higher LDL, and HIV RNA >200 copies/mL. Overweight/obese BMI and higher CD4:CD8 ratio protected against stroke/TIA.

Conclusions

Women and non-Hispanic Blacks living with HIV had the highest incidence rates of stroke/TIA. A concerted effort must be made to include PLWH from these at-risk groups in observational and interventional studies aimed at understanding stroke mechanisms and reducing stroke risk in HIV infection. Strategies to modify stroke risk in PLWH should employ a multi-pronged approach targeting vascular risk factors and engaging and retaining patients in HIV care.

Introduction

While rates of stroke are higher in persons living with HIV infection (PLWH) compared with age-matched HIV-uninfected individuals, many questions persist regarding the nature of cerebrovascular disease and associated risk factors in HIV infection. Several large observational cohort studies have demonstrated that HIV confers an increased risk of stroke, independent of traditional vascular risk factors[1–5]. The majority of these studies have relied on administrative and billing codes to define stroke outcomes from electronic medical records. Furthermore, most studies were performed using clinical care databases or clinic-based cohorts for which information on stroke and other covariates was not assessed at regular intervals or following a standardized protocol, potentially resulting in incomplete or inaccurate capture of clinical information.

We leveraged the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials (ALLRT) cohort and its parent trials to investigate incident first-ever stroke and associated risk factors in PLWH. One key strength of ALLRT is that participants were followed at regular intervals over an extended observation period and underwent standardized collection of clinical and laboratory data, including stroke events. In addition, we capitalized on the relative diversity of ALLRT to explore sex and race differences in stroke risk, based on data from other cohort studies suggesting that the additional vascular risk conferred by HIV infection may be greater in women[1,6,7] and individuals of non-White race/ethnicity[4,5].

Methods

Study population

We conducted a prospective study of antiretroviral (ART)-naïve PLWH enrolled in an ACTG trial between June 1998 and June 2011. Seven thousand seventy-three participants were randomized to receive ART in one of several ACTG parent trials (ACTG protocol 384, 388, A5014, A5095, A5142, A5202, A5257), of which 4,732 continued in ALLRT at their conclusion[8]. Participants were followed a minimum of once every 12 weeks until the completion of the parent protocol and every 16 weeks thereafter in ALLRT. We excluded individuals with a history of stroke at baseline and those who did not initiate ART or did not contribute follow-up time.

Study outcomes

We defined the primary outcome as a composite of first-ever stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) identified prospectively at study follow up visits through a centralized reporting system. TIA was defined as a focal neurologic deficit lasting >30 seconds but <24 hours with: 1) rapid evolution of symptoms to maximal deficit in less than 5 minutes followed by complete resolution; 2) no immediately preceding head trauma; 3) and no associated symptoms of seizure or migraine. Strokes were confirmed by either a demonstrable acute stroke on brain imaging or rapid onset of a focal neurologic deficit persisting for at least 24 hours and attributable to arterial obstruction or rupture in the absence of other causes.

Covariates

We collected data on the following time-varying variables: hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg irrespective of anti-hypertensive therapy use; low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level, dichotomized as < or ≥160 mg/dL; myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus; current or prior smoker; hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, defined by an existing diagnosis in ALLRT or a positive HCV antibody; body mass index (BMI), categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-24 kg/m2), overweight (25-30 kg/m2) and obese (>30 kg/m2); waist circumference, classified as increased when >102 cm for men and >88 cm for women; waist to hip ratio classified as increased when ≥0.90 for men and ≥0.85 for women; and renal dysfunction, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. Statin use (in the preceding 12 months) was available for ALLRT participants. Injection drug use was defined at baseline as never, current or previous use.

We also noted time-varying history of several central nervous system (CNS) opportunistic infections/malignancies, including toxoplasmosis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and lymphoma. We collected baseline and time-varying CD4 count, CD4 to CD8 ratio dichotomized as <0.32 and ≥0.32[9], and HIV RNA level. In addition, we examined ART use (in the preceding 12 months) by class [protease inhibitor (PI); non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI); nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI); and integrase inhibitor use]. We also evaluated abacavir and atazanavir use separately from NRTI and PI use given evidence supporting an association with (abacavir) and protective effect against (atazanavir) cardiovascular disease[3,10–12].

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics were compared between groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum and chi-square tests. First-ever stroke/TIA incidence rates per 1000 person-years (PY) were calculated overall and after stratification by age, sex and race/ethnicity. We performed unadjusted Poisson regression models with each individual baseline and time-varying covariate to identify risk factors for incident stroke/TIA. We then constructed age-adjusted Poisson models followed by models adjusted for age in addition to sex and race/ethnicity. Given the modest number of incident stroke events, we built a multivariable model (Model 1) using forward stepwise selection with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (p≤0.05 for retention in the model, p>0.10 for removal from the model). In a second multivariable model (Model 2), we forced the inclusion of two variables into Model 1 that were not retained in the forward stepwise selection (diabetes mellitus and smoking) but had face validity as established factors that impact stroke risk. We collapsed underweight and normal BMI and overweight and obese BMI, creating a 2-level variable for BMI that performed similarly to a 4-level variable in a sensitivity analysis. Missing data for each variable were represented in the analyses as missing value categories.

Out of concern for the reliability of TIA diagnoses, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding TIAs from the outcome. In addition, based on the results of the unadjusted and adjusted models, we checked for several potential statistical interactions, including differences in the association of: 1) age, race, BMI, smoking and HIV viral load with stroke risk by sex; 2) BMI with stroke risk by smoking status; 3) age with stroke risk by lower vs higher BMI; and 4) PI use with stroke risk in the time period before and after 2005. To address the potential for model overfitting, we constructed a simplified, more parsimonious multivariable model that included: sex, an age-by-sex interaction, hypertension, and BMI.

Results

Study enrollment

Of the 7,073 PLWH enrolled in an ACTG parent trial, we excluded 45 due to a history of stroke at baseline and another 95 participants who did not initiate ART or did not contribute follow-up time. Of the 45 excluded individuals with a history of stroke at baseline, 15 were women and 30 men, resulting in a higher prevalence of a history of stroke at baseline among women (1.1% for women versus 0.5% for men, p=0.023). A total of 6,933 participants were included in the analysis. The median duration of observation was 3.4 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.4, 6.4).

Demographic and clinical characteristics at entry into the parent trial

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of 6,933 participants, 20% were women, 37% were non-Hispanic Blacks and 21% were Hispanic. The median age at baseline was 37 years, and 12% of participants were ≥50 years. Prior to initiating ART, the median CD4 count was 243 cells/uL and median HIV RNA was 57,624 copies/mL. Over the total PY of observation, HIV RNA was suppressed (<200 copies/mL) 85% of the time for the entire cohort (85% for men, 83% for women). The majority of participants (91%) had no history of injection drug use.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics at the time of entry into the ACTG parent trial prior to initiation of antiretroviral therapy

| All (n=6,933) |

Men (n=5,563 |

Women (n=1370) |

P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Women, n (%) | 1,370 (20) | --- | --- | --- |

|

| ||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 37 (30,44) | 37 (30,44) | 38 (31,46) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 2,749 (40) | 2,479 (45) | 270 (20) | <0.001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2,536 (37) | 1,768 (32) | 768 (56) | |

| Hispanic (regardless of race) | 1,452 (21) | 1,149 (21) | 303 (22) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 116 (2) | 106 (2) | 10 (1) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 33 (<1) | 25 (<1) | 8 (1) | |

| More than one race/unknown | 47 (<1) | 36 (<1) | 11 (1) | |

|

Vascular and other risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%)** | 819 (12) | 649 (12) | 170 (12) | 0.72 |

|

| ||||

| LDL≥160 mg/dL, n (%)** | 143 (2) | 100 (2) | 43 (3) | 0.003 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 245 (4) | 154 (3) | 91 (7) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 42 (1) | 33 (1) | 9 (1) | 0.79 |

|

| ||||

| Renal dysfunction, n (%) | 109 (2) | 70 (1) | 39 (3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status, n (%)** | ||||

| Never | 2174 (31) | 1,682 (30) | 492 (36) | <0.001 |

| Current | 975 (14) | 771 (14) | 204 (15) | |

| Previous | 1,949 (28) | 1,624 (29) | 325 (24) | |

|

| ||||

| HCV infection, n (%) | 392 (6) | 298 (5) | 94 (7) | 0.031 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index, n (%)** | ||||

| Underweight/Normal (<24 kg/m2) | 3,654 (53) | 3,096 (56) | 558 (41) | <0.001 |

| Overweight (25-30 kg/m2) | 2,105 (30) | 1,743 (31) | 362 (26) | |

| Obese (>30 kg/m2) | 1,081 (16) | 646 (12) | 435 (32) | |

|

| ||||

| HIV factors and health-related behaviors | ||||

|

| ||||

| CD4 count (cells/mm3), median (IQR) | 243 (89, 370) | 243 (87, 371) | 244 (103, 367) | 0.70 |

|

| ||||

| HIV RNA (copies/mL), median (IQR) | 57,624 (21,430, 203,256) | 61,373 (23,966, 218,058) | 42,655 (12,666, 138,095) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Intravenous drug use, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 6,303 (91) | 5,035 (91) | 1,268 (93) | 0.053 |

| Current | 18 (<1) | 16 (<1) | 2 (<1) | |

| Previous | 612 (9) | 512 (9) | 100 (7) | |

Comparing men and women by Wilcoxon rank-sum or chi-square tests.

Data missing at entry for hypertension in 30% overall (30% of men, 30% of women); for LDL≥160 in 21% overall (21% of men, 19% of women); for smoking in 26% overall (27% of men, 25% of women); for body mass index in 1% overall (1% of men, 1% of women)

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HCV, hepatitis C virus

The race/ethnicity distribution between women and men was statistically different, with fewer non-Hispanic white women and more non-Hispanic black women compared with men (Table 1). Women were also slightly older (median 38 versus 37 years, p<0.001) and had a higher proportion of several vascular risk factors at baseline (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in CD4 count prior to initiation of ART by sex, but women had a lower HIV RNA (median 42,655 versus 61,373 copies/mL, p<0.001).

Stroke/TIA rates overall and stratified by age, sex and race/ethnicity

Fifty-four stroke/TIAs occurred over 32,023 PY (Figure 1), for an overall incidence rate of 1.69 per 1000 PY. The median years since initiation of ART at the time of stroke was 4.0 (IQR 1.9, 6.7). The risk of stroke/TIA was not significantly different between the first half (1998-2004) and second half (2005-2013) of the observation period. The incidence rate of stroke/TIA rose with older age, with 0.23 stroke/TIAs per 1000 PY for those <40 years and 7.39 per 1000 PY for those ≥60 years at the time of incident stroke (Figure 1). The incidence of stroke/TIA was higher in women compared with men overall (2.88 per 1000 PY versus 1.40 per 1000 PY, relative risk [RR] 2.07, 95% CI 1.17-3.63, p=0.01) and across all race/ethnicity groups. The age-adjusted RR of stroke/TIA for women was 1.72 (95% CI 0.96-3.09, p=0.07) (Table 2). Incidence of stroke/TIA in Hispanics combined with other race/ethnicities was 0.77 compared with 2.51 per 1000 PY in non-Hispanic Blacks (age-adjusted RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14-0.82, p=0.02) and 1.56 per 1000 PY in Whites (age-adjusted RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.34-1.05, p=0.08) (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Rates of stroke/TIA with 95% confidence intervals by time-updated age, sex and race/ethnicity.

A. Rates of stroke/TIA by age group

B. Rates of stroke/TIA with 95% confidence intervals by sex

C. Rates of stroke/TIA with 95% confidence intervals by race/ethnicity

D. Rates of stroke/TIA with 95% confidence intervals by time-updated age and sex

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted relative risk of stroke/TIA associated with demographics, vascular and HIV-related factors in the ALLRT cohort and its parent trials

| Unadjusted model | Age-adjusted | Model 11 | Model 22 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

| ||||||||

| Female sex | 2.07 (1.17-3.63) | 0.01 | 1.72 (0.96-3.09) | 0.07 | 1.94 (1.03-3.66)3 | 0.04 | 1.96 (1.04-3.67)3 | 0.04 |

|

| ||||||||

| Current age (per 10 year increase) | 2.43 (2.03-2.91) | <0.001 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| For women | 1.80 (1.35-2.40) | <0.001 | — | — | 1.49 (1.07-2.09) | 0.02 | 1.47 (1.04-2.08) | 0.03 |

| For men | 2.73 (2.19-3.41) | <0.001 | — | — | 2.44 (1.88-3.17) | <0.001 | 2.35 (1.79-3.10) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity (vs Non-Hispanic Black) | ||||||||

| Hispanic + other | 0.31 (0.13-0.74) | 0.009 | 0.34 (0.14-0.82) | 0.02 | 0.44 (0.18-1.09) | 0.08 | 0.45 (0.18-1.09) | 0.08 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.62 (0.35-1.09) | 0.1 | 0.60 (0.34-1.05) | 0.08 | 0.87 (0.46-1.64) | 0.7 | 0.90 (0.47-1.72) | 0.7 |

|

| ||||||||

| Hypertension | 5.22 (3.03-9.02) | <0.001 | 3.67 (2.06-6.56) | <0.001 | 3.64 (2.04-6.48) | <0.001 | 3.51 (1.98-6.22) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| LDL≥160 mg/dL | 2.74 (1.34-5.63) | 0.006 | 2.29 (1.11-4.75) | 0.03 | 2.41 (1.13-5.12) | 0.02 | 2.47 (1.15-5.31) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.01 (1.42-6.36) | 0.004 | 1.50 (0.68-3.30) | 0.3 | — | — | 1.57 (0.69-3.57) | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 1.32 (0.18-9.62) | 0.8 | 0.54 (0.07-4.12) | 0.6 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Renal dysfunction | 4.79 (2.61-8.79) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.03-4.10) | 0.04 | 1.90 (0.98-3.69) | 0.06 | 1.93 (1.00-3.74) | 0.05 |

|

| ||||||||

| Statin use prior 12 months | 2.17 (1.13-4.17) | 0.02 | 1.20 (0.60-2.39) | 0.6 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Current/prior smoker (vs. never) | 2.03 (1.08-3.82) | 0.03 | 1.74 (0.93-3.25) | 0.08 | — | — | 1.53 (0.83-2.84) | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||||

| Current/prior injection drug use (vs. never) | 1.22 (0.49-3.04) | 0.7 | 1.08 (0.43-2.70) | 0.9 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| HCV infection | 1.86 (0.84-4.12) | 0.1 | 1.37 (0.62-3.03) | 0.4 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Overweight/ obese BMI (vs. underweight/ normal BMI) | 0.60 (0.35-1.03) | 0.06 | 0.54 (0.31-0.92) | 0.02 | 0.43 (0.25-0.74) | 0.002 | 0.43 (0.25-0.75) | 0.003 |

|

| ||||||||

| Waist circum-ference >102 cm for men, >88 cm for women | 1.48 (0.80-2.77) | 0.2 | 1.11 (0.58-2.10) | 0.8 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Waist to hip ratio ≥0.90 for men, ≥0.85 for women | 1.78 (0.78-4.03) | 0.2 | 1.08 (0.46-2.52) | 0.9 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Baseline CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (vs. ≧ 200 cells/mm3) | 1.34 (0.79-2.29) | 0.3 | 1.16 (0.68-1.98) | 0.6 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Time-varying CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (vs. ≧ 200 cells/mm3) | 2.22 (1.14-4.30) | 0.02 | 2.42 (1.24-4.74) | 0.01 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Baseline log10 HIV RNA (per 1 log10 increase) | 0.78 (0.54-1.14) | 0.2 | 0.71 (0.48-1.05) | 0.08 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Time-varying HIV RNA >200 copies/mL (vs. ≦ 200 copies/mL) | 2.33 (1.30-4.18) | 0.005 | 3.11 (1.71-5.64) | <0.001 | 2.23 (1.19-4.16) | 0.01 | 2.19 (1.16-4.10) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||

| Time-varying CD4:CD8 ratio ≥0.32 (vs. <0.32) | 0.42 (0.24-0.73) | 0.002 | 0.39 (0.22-0.69) | 0.001 | 0.49 (0.27-0.87) | 0.01 | 0.49 (0.27-0.88) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||||

| PI use prior 12 months | 1.71 (0.98-2.97) | 0.06 | 1.80 (1.03-3.14) | 0.04 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| NRTI use prior 12 months | 0.39 (0.18-0.87) | 0.02 | 0.46 (0.20-1.04) | 0.06 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| NNRTI use prior 12 months | 0.85 (0.50-1.45) | 0.6 | 0.76 (0.45-1.30) | 0.3 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Integrase inhibitor use prior 12 months | 1.47 (0.63-3.44) | 0.4 | 1.46 (0.62-3.42) | 0.4 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Atazanavir use prior 12 months | 1.14 (0.61-2.13) | 0.7 | 1.22 (0.66-2.28) | 0.5 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Abacavir use prior 12 months | 1.16 (0.63-2.13) | 0.6 | 1.14 (0.62-2.10) | 0.7 | — | — | — | — |

Abbreviations: LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HCV, hepatitis C virus; BMI, body mass index; PI, protease inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

Model 1 adjusted for all variables shown in the column and age-by-sex interaction (p=0.01)

Model 2 adjusted for all variables in Model 1, including age-by-sex interaction (p=0.02), diabetes mellitus and smoking

Relative risk shown for female sex in Models 1 and 2 is at 50 years of age

Vascular risk and HIV-related risk factors for stroke/TIA

In age-adjusted analyses, several variables were associated with a higher RR of stroke/TIA (Table 2). Of vascular risk factors, hypertension was associated with the highest risk of stroke/TIA with a RR of 3.67 (95% CI 2.06-6.56). An LDL ≥160 mg/dL more than doubled the risk of stroke/TIA, as did renal dysfunction. While being a smoker was associated with an increased risk of stroke/TIA in an unadjusted model, this association no longer reached statistical significance after adjusting for age (Table 2). In age-adjusted models, we also did not observe a statistically significant association between diabetes mellitus, injection drug use, and HCV infection on stroke/TIA risk. Having an overweight/obese BMI was protective against stroke/TIA (RR 0.54, 95% 0.31-0.92, p=0.02).

Among HIV-related risk factors, recent viremia (HIV RNA >200 copies/mL) conferred over three-fold higher risk of stroke/TIA (age-adjusted RR 3.11, 95% CI 1.71-5.64). A recent CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 was associated with over twice the risk of stroke/TIA, while a CD4 to CD8 ratio ≥0.32 was associated with a 60% reduction in stroke/TIA risk (Table 2). Results were similar when analyzing continuous CD4:CD8 ratio (age-adjusted RR 0.52 per 0.5 units higher, 95% CI 0.34-0.78, p=0.002). Use of a PI was also a risk factor for stroke/TIA in an age-adjusted model, although it was not retained in the final multivariable model. We did not find a statistically significant association of abacavir or atazanavir use with stroke/TIA risk.

We observed a statistically significant interaction between age and sex on stroke risk, which we included in age, sex, and race-adjusted models. The addition of sex, race, and an age-by-sex interaction term did not appreciably change the RR point estimates compared with the models adjusted only for age for most of the vascular and HIV-related covariates (Supplemental Table).

In a multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, an age-by-sex interaction term, race/ethnicity, LDL level, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, BMI, smoking, renal dysfunction, time-varying HIV RNA level and CD4 to CD8 ratio (Model 1), older age was associated with a higher risk of stroke/TIA for women and men, although the effect of age was greater for men (RR 2.44 for every 10 years for men, 95% CI 1.88-3.17 vs. RR 1.49 for every 10 years for women, 95% CI 1.07-2.09). At close to the median age when stroke/TIAs occurred (50 years), women had almost twice the stroke/TIA risk compared with men (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.03-3.66). At younger ages, the higher risk in women was even more pronounced. For example, at 40 years of age, women had over 3 times the stroke/TIA risk compared with men (RR 3.17, 95% CI 1.45-6.93). We observed a trend toward Hispanic combined with other race/ethnicities being protective against stroke/TIA compared with non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity. Of vascular risk factors, hypertension, LDL ≥160 mg/dL, and renal dysfunction conferred greater risk of stroke/TIA, while overweight/obese BMI was associated with a lower risk of stroke/TIA (Table 2, Figure 2). Of HIV-related factors, recent HIV RNA >200 copies/mL was a risk factor for stroke/TIA, whereas a CD4 to CD8 ratio ≥0.32 was associated with a lower risk of stroke/TIA. Forced inclusion of diabetes mellitus and smoking (Model 2) did not significantly impact the associations observed in Model 1.

Figure 2.

Multivariable model of relative risk of stroke/TIA in ALLRT cohort. Model adjusted for all variables shown in the figure and age-by-sex interaction.

Sensitivity analyses

In a sensitivity analysis restricted to strokes (n=41), the results of the multivariable model were comparable to when TIAs were included, although the estimated effect of certain risk factors (e.g., female sex at 50 years of age, LDL ≥160 mg/dL) no longer reached statistical significance. None of the interactions that we tested for were statistically significant aside from the interaction between age and sex on stroke risk, which was included in the multivariable models (Table 2). Results from a simplified, more parsimonious multivariable model that included sex, an age-by-sex interaction, hypertension, and BMI (Supplemental Table) were highly comparable to the full multivariable models (Models 1 and 2 from Table 2).

Discussion

The incidence of stroke/TIA was highest in women and non-Hispanic Blacks in this cohort of PLWH followed regularly in ALLRT and its ACTG parent trials. In age-adjusted models, non-Hispanic Blacks had a higher RR of stroke/TIA when compared with Hispanic and other race/ethnicities, although this effect no longer reached statistical significance in multivariable models. We also observed higher overall rates of stroke/TIA in women compared with men and found a significant interaction between age and sex on stroke/TIA risk. The increased RR of stroke/TIA in women was most pronounced in the 40 to 49 year age group and diminished with older age, while older age conferred a greater increase in stroke/TIA risk in men than women. Although we observed differences in age, race/ethnicity, and HIV RNA level between women and men, as well as several vascular risk factors at entry, the higher RR of stroke/TIA in women was still present after accounting for these factors in multivariable analyses.

Data from several large cohorts have suggested that vascular risk conferred by HIV may be greater in women than in men[1,2,6,7,13]. In the studies focused on cerebrovascular disease, absolute rates of stroke in women were still lower than in men[1,2], which is in line with the known epidemiology of stroke in the general population[14]. Our data are the first to suggest that women living with HIV may be at greater absolute risk of stroke/TIA compared with men. A similar finding of higher absolute rates of stroke in women with HIV has been presented from the Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) cohort, with an age-standardized incidence of stroke among women of 5.02 compared with 2.88 per 1000 PY in men[15], and should additionally be confirmed in other studies.

One proposed mechanism underlying observed sex differences in HIV-associated vascular risk is increased immune activation in women. Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR-7), which mediates innate immunity and activates monocytes, has been shown to promote greater levels of interferon-alpha in women with HIV compared with men, independent of the degree of viremia present[16]. Higher markers of monocyte activation have been detected in women with HIV, even after initiation of ART with successful virologic suppression, compared with: 1) men with HIV and 2) men and women without HIV[17]. Moreover, the prevalence of noncalcified coronary plaque, a biomarker of cardiovascular risk, was higher in women with treated HIV and correlated with elevated monocyte activation, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

Declining estrogen levels in menopause, which affects immune activation and leads to a shift to a more proinflammatory state,[18–20] may also modify the effect of HIV on vascular risk in women. In one study, reduced ovarian reserve contributed more to the burden of noncalcified coronary plaque among women with treated, virologically suppressed HIV than traditional vascular risk factors, whereas in uninfected women, the reverse was true[21]. One explanation of the observed age-by-sex interaction is that perimenopause may be a high-risk transition phase for women with HIV, leading to increased stroke rates. Then, as women reach post-menopause and more advanced age, female sex confers less of an increase in stroke risk among PLWH, while older age plays a greater role. Markers of immune activation and reliable data on menopause status and other women-specific stroke risk factors[22] (e.g., pregnancy, estrogen use) were not available in our study. A crucial next step will be to investigate how immune activation, menopause and other women-specific stroke risk factors, which can vary across the life course and thus may exert variable effects on stroke risk at different ages, interact and influence stroke risk in women living with and without HIV.

Non-Hispanic Blacks were also noted to have higher rates of stroke/TIA compared with individuals of Hispanic and other race/ethnicities and non-Hispanic Whites, which is consistent with previously published studies of ischemic stroke risk in the general population, particularly in younger age groups[14,23,24]. This disparity is mediated, in part, by higher prevalence and worse control of traditional vascular factors among non-Hispanic Blacks[25]. Indeed, we found that the higher RR of stroke/TIA among non-Hispanic Blacks compared with non-Hispanic Whites was no longer present after adjusting for various risk factors, including hypertension, elevated LDL, and smoking. However, the trend toward a higher RR of stroke/TIA for non-Hispanic Blacks compared with Hispanics and other race/ethnicities after adjusting for traditional vascular and HIV-related risk factors raises the possibility that novel unmeasured factors may also be at play. Higher ischemic stroke risk for Blacks has been noted in other observational cohort studies, including in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study-Virtual Cohort[5] and the Kaiser Permanente California database[4]. We also recently demonstrated in a group of ART-treated, virologically suppressed PLWH that Blacks have worse cerebrovascular endothelial function compared with other race/ethnicities, independent of several traditional vascular risk factors[26]. Studies aimed at identifying mechanisms underlying vascular risk in HIV infection and developing novel strategies to reduce risk must have sufficient representation of non-White race/ethnicities and women in order to understand disparities and to evaluate the efficacy of therapies in the highest-risk groups.

Several traditional vascular risk factors, including hypertension and elevated LDL, were associated with a higher RR of stroke. Aggressive risk factor modification will be essential to stem the inevitable tide of stroke and other vascular complications as PLWH age[27]. In light of known discrepancies in risk factor control by race/ethnicity in the general population in the U.S.[28,29], particular attention to risk factor modification may be warranted in our patients of non-White race/ethnicity.

Of HIV-related risk factors associated with a higher risk of stroke/TIA, a non-suppressed viral load conferred the greatest increase in stroke/TIA risk. Lower CD4 count was also a strong risk factor for stroke/TIA in age- and demographics-adjusted models but fell out of the multivariable model, likely due to collinearity with the presence of viremia. Importantly, we investigated whether the association of strokes with worse control of HIV infection may have been explained by strokes or misclassified strokes in the setting of common CNS opportunistic infections or malignancy. Of the 54 stroke/TIAs in the cohort, not one was associated with a recent diagnosis of a CNS infection or malignancy. The strong association of viral load and CD4 count with stroke/TIA generates the hypothesis that the immunologic sequelae of uncontrolled viremia may contribute to stroke risk in HIV infection. While we did not have markers of immune activation for most of the individuals in the cohort, we found in age-adjusted and multivariable models that a higher CD4 to CD8 ratio was protective against stroke/TIA. The CD4 to CD8 ratio has been suggested as a proxy for immune activation and immunosenescence in HIV infection and is associated with an increased risk of several non-AIDS-related outcomes, including cerebrovascular events[30,31]. The strength of the association between lower CD4 to CD8 ratio and higher stroke/TIA risk was present even in a multivariable model adjusted for detectable viremia, suggesting that immune activation, which is a risk factor for stroke in the general population[32], may contribute to cerebrovascular risk in HIV infection independent of viral load.

One surprising finding was the protective effect that obesity had on stroke/TIA risk in the cohort. A similar effect of overweight/obese BMI on stroke risk in HIV infection was observed in the Kaiser Permanente California cohort[4]. Other studies have found a paradoxical association between higher BMI or plasma leptin, an adipokine directly correlated with fat cell mass, and lower cardiovascular risk[33–35]. The association between higher BMI and stroke risk could be confounded by overall health status, as individuals with higher BMI may be healthier and have better control of their HIV infection. However, the protective effect of higher BMI on stroke/TIA risk remained after adjustment for uncontrolled viremia. We also did not find a statistically significant interaction between BMI and age, sex or smoking status to indicate that the protective effect of higher BMI was primarily in specific subgroups. Because BMI does not account for body fat distribution, we also investigated markers of abdominal obesity. Neither greater waist to hip ratio nor greater waist circumference was associated with a significant decrease or increase in stroke/TIA risk in unadjusted or age-adjusted models. While a provocative finding, the effect of overweight/obese BMI should be investigated in other cohorts before specific recommendations can be made regarding ideal BMI in PLWH.

Our study has several limitations. While a physician reviewed data forms for the majority of reported stroke/TIAs, events were not formally adjudicated for this cohort. As a result, there may have been misclassification of outcomes, although this should not have been more or less likely based on sex or race/ethnicity. We also were not able to distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. While prior data have demonstrated that HIV is an independent risk factor for both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes[1,2], the pathophysiology underlying each differs and should ideally be studied separately. Differential loss-to-follow-up is always a potential source of bias in observational studies. In the ALLRT cohort, men were more likely to go off-study than women[36], although the implications on our findings of differential loss-to-follow-up by sex and other factors are unknown. In prior ALLRT analyses that have used statistical methods to correct for differential loss to follow up[37], findings were similar in adjusted and unadjusted analyses. While model overfitting was a concern given the modest number of events, we felt reassured by the highly comparable results between the full multivariable models (Models 1 and 2) and both the demographics-adjusted models and the simplified multivariable model (Supplemental Table). However, our finding that women have higher absolute rates of stroke compared with men should be interpreted cautiously in light of the modest number of stroke events overall and in women.

In summary, in this large observational cohort of PLWH randomized to ART in one of several ACTG clinical trials, the highest incidence of stroke/TIA was among women and non-Hispanic Blacks. Special attention should be paid to these at-risk populations as we design and implement studies focused on understanding and reducing elevated stroke risk in HIV infection. In addition to aggressively targeting modifiable vascular risk factors, efforts to engage and retain patients in care are paramount to addressing the role of uncontrolled viremia in stroke risk in HIV infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NCATS KL2TR000143 and NIH/NIAID UM1AI068634 and UM1AI068636. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sponsors. We are immensely grateful to the staff at the ACTG Clinical Research Sites and the study participants who made this work possible.

Funding sources: This work was supported by NIH/NCATS KL2TR000143 and NIH/NIAID UM1AI068634 and UM1AI068636.

References

- 1.Chow FC, Regan S, Feske S, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Comparison of Ischemic Stroke Incidence in HIV-Infected and Non-HIV-Infected Patients in a US Health Care System. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:351–358. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825c7f24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow FC, He W, Bacchetti P, Regan S, Feske SK, Meigs JB, et al. Elevated rates of intracerebral hemorrhage in individuals from a US clinical care HIV cohort. Neurology. 2014;83:1705–1711. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen LD, Engsig FN, Christensen H, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, Pedersen C, et al. Risk of cerebrovascular events in persons with and without HIV. AIDS. 2011;25:1637–1646. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283493fb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Chao CR, Chow FC, Horberg MA, Hurley LB, et al. HIV infection and incidence of ischemic stroke. AIDS. 2014;28:1911–1919. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sico JJ, Chang C-CH, So-Armah K, Justice AC, Hylek E, Skanderson M, et al. HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology. 2015;84:1933–1940. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, Gilquin J, Partisani M, Simon A, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS. 2010;24:1228–1230. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339192f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smurzynski M, Collier AC, Koletar SL, Bosch RJ, Wu K, Bastow B, et al. AIDS clinical trials group longitudinal linked randomized trials (ALLRT): rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. HIV Clinical Trials. 2008;9:269–282. doi: 10.1310/hct0904-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt PW, Crane HM, Drozd DR, Floris-Moore M, Moore RD, Kitahata MM, et al. CRP, d-dimer and oxidized LDL predict myocardial infarction in treated HIV infection. Presented at the 23rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA, USA. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi AI, Vittinghoff E, Deeks SG, Weekley CC, Li Y, Shlipak MG. Cardiovascular risks associated with abacavir and tenofovir exposure in HIV-infected persons. AIDS. 2011;25:1289–1298. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328347fa16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein JH, Ribaudo HJ, Hodis HN, Brown TT, Tran TTT, Yan M, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of antiretroviral therapies on carotid wall thickness. AIDS. 2015;29:1775–1783. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lafleur J, Bress AP, Rosenblatt L, Crook J, Sax PE, Myers J, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes among HIV-infected veterans receiving atazanavir. AIDS. 2017 Jul 7; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001594. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savès M, Chêne G, Ducimetière P, Leport C, Le Moal G, Amouyel P, et al. Risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:292–298. doi: 10.1086/375844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tirschwell DT, Chow FC, Becker KJ, et al. Incidence of Stroke in the US Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) Cohort. Abstract presented at: 69th Annual American Academy of Neurology Meeting; April 2017; Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier A, Chang JJ, Chan ES, Pollard RB, Sidhu HK, Kulkarni S, et al. Sex differences in the Toll-like receptor–mediated response of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to HIV-1. Nat Med. 2009;15:955–59. doi: 10.1038/nm.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitch KV, Srinivasa S, Abbara S, Burdo TH, Williams KC, Eneh P, et al. Noncalcified Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque and Immune Activation in HIV-Infected Women. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1737–1746. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasui T, Maegawa M, Tomita J, Miyatani Y, Yamada M, Uemura H, et al. Changes in serum cytokine concentrations during the menopausal transition. Maturitas. 2007;56:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cioffi M, Esposito K, Vietri MT, Gazzerro P, D'Auria A, Ardovino I, et al. Cytokine pattern in postmenopause. Maturitas. 2002;41:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harkonen PL, Vaananen HK. Monocyte-Macrophage System as a Target for Estrogen and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:218–227. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Looby SE, Fitch KV, Srinivasa S, Lo J, Rafferty D, Martin A, et al. Reduced ovarian reserve relates to monocyte activation and subclinical coronary atherosclerotic plaque in women with HIV. AIDS. 2016;30:383–93. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, Chireau MV, Fedder WN, Furie KL, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:1545–1588. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000442009.06663.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard G, Kissela BM, Kleindorfer DO, McClure LA, Soliman EZ, Judd SE, et al. Differences in the role of black race and stroke risk factors for first vs recurrent stroke. Neurology. 2016;86:637–642. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, Alwell K, Woo D, Flaherty ML, et al. Stroke Incidence Is Decreasing in Whites But Not in Blacks: A Population-Based Estimate of Temporal Trends in Stroke Incidence From the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study * Supplemental Material. Stroke. 2010;41:1326–1331. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutierrez J, Williams OA. A decade of racial and ethnic stroke disparities in the United States. Neurology. 2014;82:1080–1082. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow FC, Boscardin WJ, Mills C, Ko N, Carroll C, Price RW, et al. Cerebral vasoreactivity is impaired in treated, virally suppressed HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2016;30:45–55. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, et al. Morbidity and Aging in HIV-Infected Persons: The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1130–1139. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redmond N, Baer HJ, Hicks LS. Health Behaviors and Racial Disparity in Blood Pressure Control in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2011;57:383–389. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Rekeneire N, Rooks RN, Simonsick EM, Shorr RI, Kuller LH, Schwartz AV, et al. Racial differences in glycemic control in a well-functioning older diabetic population: findings from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1986–1992. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serrano-Villar S, Sainz T, Lee SA, et al. HIV-infected individuals with low CD4/CD8 ratio despite effective antiretroviral therapy exhibit altered T cell subsets, heightened CD8+ T cell activation, and increased risk of non-AIDS morbidity and mortality. PLoS Pathogens. 2014;10:e1004078. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano-Villar S, Pérez-Elías M-J, Dronda F, Casado J-L, Moreno A, Royuela A, et al. Increased Risk of Serious Non-AIDS-Related Events in HIV-Infected Subjects on Antiretroviral Therapy Associated with a Low CD4/CD8 Ratio. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e85798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esenwa CC, Elkind MS. Inflammatory risk factors, biomarkers and associated therapy in ischaemic stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Gange SJ, Benning L, Jacobson LP, Lazar J, et al. Low CD4+ T-cell count as a major atherosclerosis risk factor in HIV-infected women and men. AIDS. 2008;22:1615–1624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328300581d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hileman CO, Longenecker CT, Carman TL, Milne GL, Labbato DE, Storer NJ, et al. Elevated D-dimer is independently associated with endothelial dysfunction: a cross-sectional study in HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:1345–1349. doi: 10.3851/IMP2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longenecker CT, Dunn W, Jiang Y, Debanne SM, McComsey GA. Adipokines and vascular health in treated HIV infection. AIDS. 2013;27:1353–1356. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283606c11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishnan S, Wu K, Smurzynski M, Bosch RJ, Benson CA, Collier AC, et al. Incidence Rate of and Factors Associated with Loss to Follow-up in a Longitudinal Cohort of Antiretroviral-Treated HIV-Infected Persons: An AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials (ALLRT) Analysis. HIV Clinical Trials. 2015;12:190–200. doi: 10.1310/HCT1204-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lok JJ, Bosch RJ, Benson CA, Collier AC, Robbins GK, Shafer RW, et al. Long-term increase in CD4+ T-cell counts during combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2010;24:1867–1876. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833adbcf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.