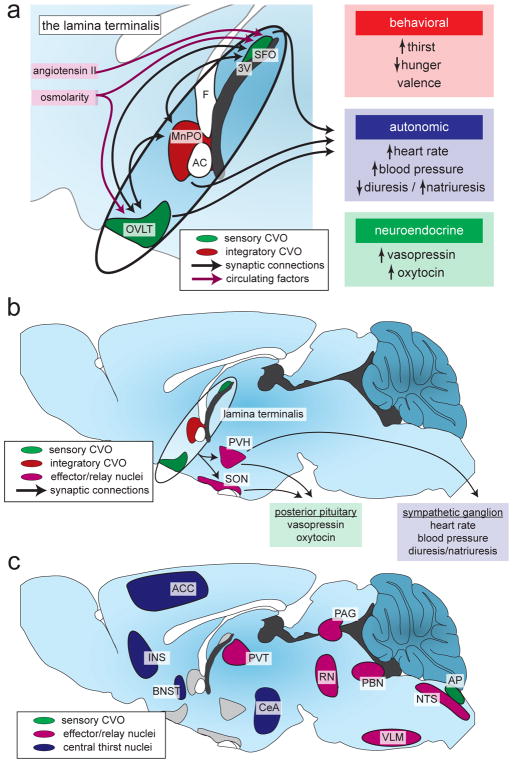

Figure 3. The neural circuit that controls thirst.

(A) A set of integrated brain structures called the lamina terminalis monitors the state of the blood and generates appropriate motivational, autonomic, and hormonal responses. The subfornical organ (SFO) and organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT) directly sense circulating factors and, along with the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO), integrate this information and communicate with downstream brain regions. 3V, third ventricle; AC, anterior commissure; F, fornix.

(B) The downstream circuit that controls the autonomic and hormonal responses to fluid imbalance relies on projections from the lamina terminalis to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) and the supraoptic nucleus (SON).

(C) The downstream circuit that generates thirst is less clear, although many brain regions have been implicated in the central representation of thirst and as relay and effector/output nuclei. These brain regions were identified using Fos mapping studies in rodents and fMRI/PET mapping studies in humans. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AP, area postrema; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; CeA, central amygdala; INS, insular cortex; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; PVT, paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus; RN, raphe nuclei; VLM, ventrolateral motor nucleus.