Abstract

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a common, chronic debilitating condition. Surgical management traditionally involves fundoplication. Magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) is a new definitive treatment. We describe our experience of introducing this innovative therapy into NHS practice and report the early clinical outcomes.

Methods

MSA was introduced into NHS practice following successful acceptance of a cost-effective business plan and close observation of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations for new procedures, including a carefully planned prospective data collection over a two-year follow-up period.

Results

Forty-seven patients underwent MSA over the 40-month period. Reflux health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL) was significantly improved after the procedure and maintained at one- and two-year (P < 0.0001) follow-up. Drug dependency went from 100% at baseline to 2.6% and 8.7% after one and two years. High levels of patient satisfaction were reported. There were no adverse events.

Conclusions

MSA is highly effective in the treatment of uncomplicated GORD, with durable results and an excellent safety profile. This laparoscopic, minimally invasive procedure provides a good alternative for patients where surgical anatomy is unaltered. Our experience demonstrates that innovative technology can be incorporated into NHS practice with an acceptable business plan and compliance with NICE recommendations.

Keywords: Reflux, Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation, NICE

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a common, chronic and debilitating condition.1,2 It usually occurs in association with a defective barrier mechanism between the oesophagus and stomach, causing excessive exposure of the distal oesophagus to gastric fluids. Inflammatory damage (oesophagitis) occurs and clinical symptoms present.3 Consequently, permanent changes including stricturing and premalignant transformation may develop.4

Symptoms of reflux can have a profound detrimental impact on an individual’s quality of life and wellbeing.5 Heartburn, regurgitation, retrosternal discomfort, chest pain and dysphagia are classical features. Extra-oesophageal manifestations such as chronic cough, wheezing and hoarse voice are also frequently reported. Diagnosis is confirmed with a combination of endoscopic, radiological and physiological investigations.6

Medical therapy with proton-pump inhibitors, H2 antagonists (H2A) and other antacids can temporarily control symptoms. However, drug dependency results, with adverse effects and exposure to long-term complications. Many patients suffer symptom breakthrough, necessitating dose escalation and polypharmacy.7–9 Medical therapy does not address the underlying pathophysiology.10–12 Consequently, the NHS annually experiences at least 4% of the population seeking primary health care advice for GORD symptoms and over one in four of these patients are referred to a hospital for further evaluation and testing.10,13

GORD represents a significant financial burden on health services. In 2016/17, this condition resulted in around 101,695 consultant outpatient attendances in the NHS in England14 and drug therapy expenses of approximately £625 million per year.10 It has been estimated that additional costs of endoscopic evaluations, over the counter drug sales and sick leave are included, the total may be at least £1.5 billion for the NHS.10

Healthcare practice in the NHS follows guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).15 The NICE clinical guideline on the management of GORD and dyspepsia in adults recommends that surgical therapy be reserved for patients with a confirmed diagnosis of acid reflux and adequate symptom control with acid suppression therapy but who do not wish to continue with this therapy long term, with a confirmed diagnosis of acid reflux and symptoms that are responding to a proton-pump inhibitor but who cannot tolerate acid suppression therapy.15

Surgical therapy is aimed at improving the barrier mechanism, which is a combination of the lower oesophageal sphincter and diaphragmatic crural sling. A defective lower oesophageal sphincter and/or the presence of a hiatal hernia usually contribute to symptoms of GORD.16 Traditionally, a tissue fundoplication has been offered, where part (partial) or all (total) of the fundus is used to create a new valve around the distal oesophagus. This eliminates reflux symptoms and the dependence on drug therapy. Despite popularisation in the laparoscopic era, this remains a relatively uncommon intervention. Reasons for this may include the reported adverse-effect profile of surgery (dysphagia, inability to belch or vomit, bloating, flatulence) or the perception of the surgery itself, which may be regarded as a major reconstructive procedure. Considerable variability exists between different techniques and indeed individual surgeons, resulting in a wide discrepancy in reported long-term outcomes.

Magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) using the LINX™ device offers a less invasive and attractive alternative surgical therapy. In this procedure, a customised set of titanium beads with magnetic cores is placed around the distal oesophagus. This enhances the natural lower oesophageal sphincter, preventing excessive reflux, yet opening in response to oesophageal peristalsis or increased intragastric pressure. Consequently, the objectives of reflux elimination and obviation of drug dependency are still achieved but with a diminished adverse-effect profile and a substantially less invasive intervention.

As a new procedure, MSA was the subject of Interventional Procedures guidance from NICE (IPG431 September 2012), which had concluded that the evidence on its safety and efficacy was limited; hence the MSA should only be used with ‘special arrangements for clinical governance, consent and audit or research’. 17 The NICE guidance encouraged publication of further evidence.

As one of the first centres to have introduced the MSA in the UK within the NHS in June 2012, we share our experience. This study prospectively evaluates the effectiveness of this treatment.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective, observational single arm study on all MSA procedures performed between June 2012 and October 2015 at a specialist anti-reflux centre. Preoperative data relating to patient demographics, drug usage, oesophageal physiology and symptom scores related to quality of life were collected. Outcomes analysed were GERD health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL) scores,18 drug use and patient satisfaction at one, two and three-year follow up.

In order to introduce MSA, we addressed two issues which are now fundamental to the adoption of any new procedure, and which required close liaison with hospital managers:

We confirmed with NICE that MSA had been notified as a new procedure and that it was in the process of evaluation. Arrangements were made in line with guidance for clinical governance, consent, audit and research. The NICE interventional procedures guidance was published in September 2012 and we were fully compliant with its recommendations, including detailed written information for patients, specific consent forms and designed a detailed system for prospective audit of all patients. The latter underpins the methods of this report, which in turn support the NICE recommendation to publish outcomes of MSA.

We produced a detailed business case to demonstrate that the likely cost of the procedure, including purchase cost of the LINX device, would be similar to a fundoplication procedure and within NHS tariff.

A cost-effective business case was submitted to offer LINX with the same NHS tariff as fundoplication. The cost of the implant was offset against savings made from reduced usage of surgical equipment, operating time, inpatient stay/readmission and the potential for income generation as a consequence.

Study population and characteristics

All patients who underwent MSA procedure for reflux were included in the study. The diagnosis of GORD was confirmed with a 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring, with an overall DeMeester score greater than 14.72 being regarded as abnormal.

Baseline and follow-up

Baseline data were collected preoperatively, using a standardised questionnaire. Follow-up data were collected via formal telephone clinics at 12-monthly intervals, using a standardised questionnaire. Reflux-related quality of life was assessed using the validated GERD-HRQL tool (Table 1).18

Table 1.

Reflux-related quality of life was assessed using the validated GERD-HRQL tool.18

| Question | Score | ||||

| 1. How bad is your heartburn? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Heartburn when lying down? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Heartburn when standing up? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Heartburn after meals? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Does heartburn change your diet? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Does heartburn wake you from your sleep? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Do you have difficulty swallowing? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Do you have pain with swallowing? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Do you have bloating or gassy feelings? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. If you take medication, does this affect your daily life? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. How satisfied are you with your present condition? | Satisfied | Neutral | Dissatisfied | ||

Scale:

0 = No symptoms

1 = Symptoms noticeable but not bothersome

2 = Symptoms noticeable and bothersome, but not every day

3 = ymptoms bothersome every day

4 = Symptoms affect daily life

5 = Symptoms are incapacitating, unable to do daily activities

Surgical procedure

MSA was performed as a daycase laparoscopic procedure. The technique has been described elsewhere,4,19 but in brief involves the following:

General anaesthesia with standard operative set-up as per laparoscopic fundoplication. Pneumoperitoneum and placement of 2 x 12 mm; 2 x 5 mm and Nathanson’s liver retractor.

Minimal dissection with partial division of the phreno-oesophageal ligament to enable access to the distal oesophagus.

Creation of a window between the posterior vagus and the oesophagus.

Application of the LINX sizing device.

Insertion and locking of the LINX device.

Crural repair (if necessary) with 0-Ethibond™.

Postoperative care

Patients were normally discharged home on the same day with instructions for wound care, analgesia and postoperative information. No specific dietary restrictions were imposed but all patients were encouraged to chew their food well with plenty of fluids. A 24-hour/7-day contact card was provided for any advice, if required. Use of anti-reflux medication could be stopped immediately.

Data entry and statistical analysis

Data were collected and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for review and analysis. Statistical analysis and graphical representations were done using statistical tool packages JMP® and Stata 13.1™. A two-tailed, paired student t-test was used to compare pre- and postoperative values; only available data were analysed and results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

In total, 47 patients (37 male and 10 female) with a mean age of 53.6 years (median 53 years, range 43.3–63 years) underwent MSA insertions over a period of 40 months (1 June 2012 to 31 October 2015). Preoperatively, all patients were dependant on drugs for reflux control and had an abnormal acid exposure with a mean DeMeester score of 34.15 (median 30.14, range 25.1–40.2) and a mean baseline GERD-HRQL score of 25.80 (median 25, Range 19.25–34.5).

All procedures were carried out successfully via a laparoscopic approach with no perioperative complications or adverse events. Mean operative time for MSA device insertions (defined as ‘skin to skin’ time) was 73 minutes (median 74 minutes, range 46–111 minutes). All patients were discharged either the same day or after an overnight hospital stay. Only one patient was readmitted within a 30-day period, for dysphagia, which settled spontaneously.

Two patients (4.2%) required an endoscopic balloon dilatation post-MSA insertion during their follow-up periods. One patient required a dilatation on two separate occasions, at 6 months and 13 months, and the other patient at 9 months. There were no MSA device removals in this study.

Long-term outcomes

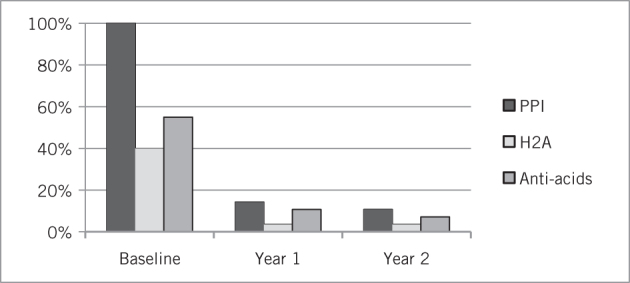

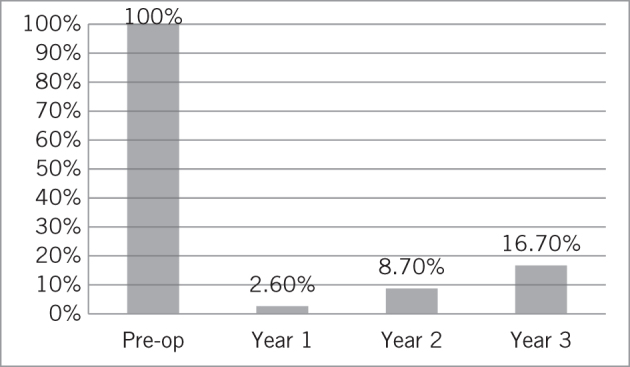

At three-year follow-up, a mean GERD-HRQL score of 5.1 (median 4.5, range 0–12) was recorded on the six patients observed for that length of time. Freedom from the use of any anti-reflux medication was noted in 97.4% of patients at year 1, 91.3% at year 2 and 83.3% at year 3 (Figs 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Use of anti-reflux medication in patients postoperatively

Figure 2.

Drug dependency in patients preoperatively and at one, two and three years postoperatively

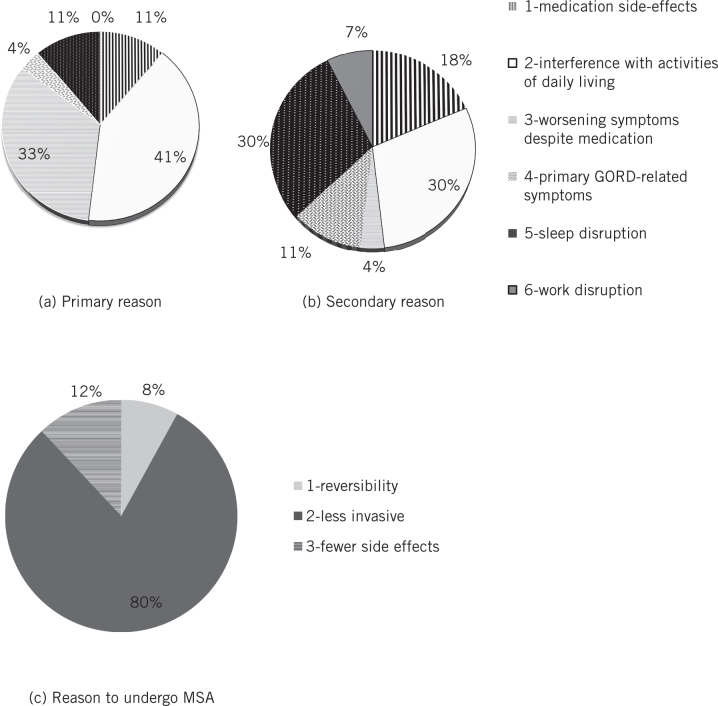

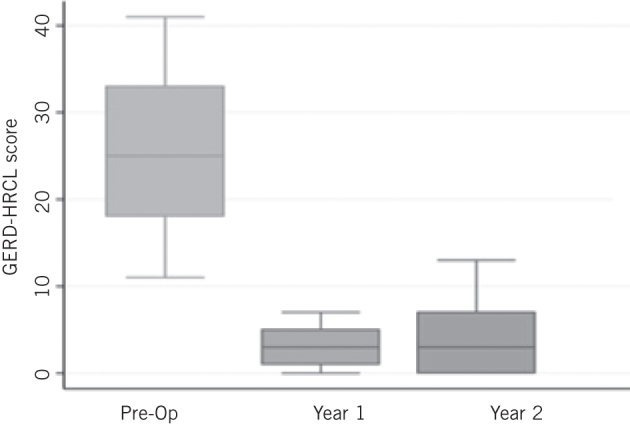

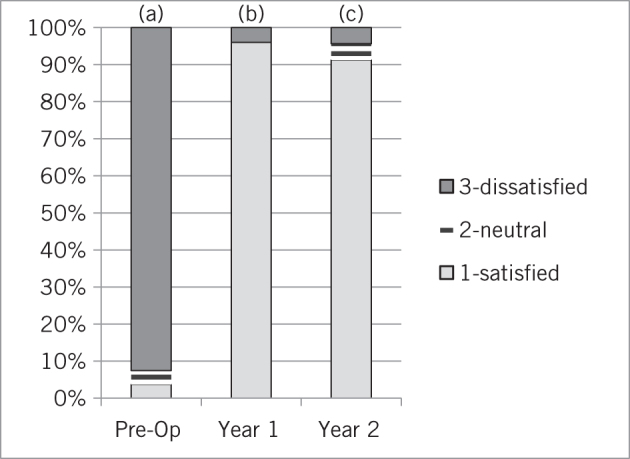

GERD-HRQL was significantly improved at year 1 and this was maintained at years 2 and 3 (baseline score 25.7; year 1 5.1, P < 0.0001; year 2 score 4, P < 0.0001; year 3 score 5.2, P < 0.0001) on follow-up (Fig 3). Before surgery, 92.6% of patients were dissatisfied with their condition and this number dropped at 1-, 2- and 3-year follow-up to 2.6%, 8.7% and 16.7%, respectively (Fig 4). Reported symptoms of dysphagia and gas bloat were unchanged before and after surgery. Primary and secondary reasons for taking any type of anti-reflux surgery and for choosing MSA were also collected (Fig 5).

Figure 3.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL) preoperatively and at one and two years postoperatively

Figure 4.

Patient satisfaction preoperatively and at one and two years postoperatively

Figure 5.

Primary and secondary reasons for taking any type of anti-reflux surgery and reasons for choosing MSA

Discussion

Our experience with MSA supports the existing published evidence that this procedure represents a viable alternative to standard fundoplication in the surgical management of reflux disease.1,2,4,17 Improvement in health-related quality of life and reduced drug dependency were observed and maintained. The procedure is highly suited to the daycase surgery environment and no adverse events occurred.

The safety profile of the MSA device has already been extensively reported.20 Data collected from published studies and literature, the manufacturer’s database and the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database, including 1000 patients undergoing MSA insertions between 2007–2013, corroborated early safety reports.21 Only 5.6% of patients required endoscopic dilation for dysphagia and 3.4% required device removal. Further studies have reported a reduction in these reinterventions, with increasing experience of the operating surgeons. The current rate of device removal is under 1%.22 Three and five-year follow-up studies on the MSA device have shown that it provides symptomatic relief for GORD with minimal side-effects. Safe removal can be facilitated if required.4,23,24

Our experience in introducing MSA, however, does expose some of the unique difficulties relating to the adoption of novel procedures into NHS practice, in particular when a significant capital cost is involved. Local and trust-based NHS managements are under pressure not to support local treatment, which is perceived to be more expensive than existing options, even if there are substantial tangible of benefits to the overall general health of the population and long-term cost savings for the healthcare system itself.

In the example of MSA, the capital expense of the device is ultimately compensated by a reduction in drug therapy costs. Dealing with the consequences of chronic reflux disease and improved health and wellbeing results in improved occupational productivity and less dependence of social welfare support. These benefits are difficult to quantify, however, particularly in relation to single-year financial planning budgets.

NICE Interventional Procedures guidance and its ‘special arrangements’ recommendations can inadvertently be used as an obstacle to develop such innovations. This can lead to considerable frustration for patients, primary medical practitioners and specialist clinicians. The NICE Interventional Procedure Guidance 431, while concluding that the evidence of safety and efficacy of MSA was limited, encouraged the production and publication of its use to boost the evidence base.17 This does not explicitly support the use of MSA as a recommended surgical option for chronic GORD. Whilst NICE planned to review the evidence in 2017, paradoxically, if NHS trusts are not supportive of MSA on the basis of current NICE guidance, then these data will be difficult to generate. Consequently, MSA will remain perpetually on restricted availability (private sector) in the UK yet will flourish in the Western Europe and the United States, as is already being observed.20,25

Conclusions

MSA is a safe and effective minimally invasive surgical treatment for chronic GORD. It offers a viable alternative to permanent medical therapy or fundoplication. Incorporation into standard NHS practice is a challenge in the current climate of financial constraint. NICE guidance may be being used as a tool to inadvertently restrict, rather that encourage, its development in the UK. This might prove to be ultimately detrimental to population health care, both medically and financially in the long term.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. SW is a preceptor for the MSA procedure. BC is a Past Chair of the NICE Interventional Procedures Advisory Committee.

Acknowledgement

This study contributed data to the International LINX Registry, funded by Torax Medical.

References

- 1.Schwameis K, Schwameis M, Zorner B et al. Modern GERD treatment: feasibility of minimally invasive esophageal sphincter augmentation. 2014; : 2,341–2,348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saino G, Bonavina L, Lipham JC et al. Magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux at 5 years: final results of a pilot study show long-term acid reduction and symptom improvement. 2015; : 787–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunbar KB, Agoston AT, Odze RD et al. Association of acute gastroesophageal reflux disease with esophageal histologic changes. 2016; : 2,104–2,012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonavina L, Saino G, Bona D et al. One hundred consecutive patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease: 6 years of clinical experience from a single center. 2013; : 577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiklund I. Review of the quality of life and burden of illness in gastroesophageal reflux disease. 2004; : 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jobe BA, Richter JE, Hoppo T et al. Preoperative diagnostic workup before antireflux surgery: an evidence and experience-based consensus of the Esophageal Diagnostic Advisory Panel. 2013; : 586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. 2013; : 308–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah NH, LePendu P, Bauer-Mehren A et al. Proton pump inhibitor usage and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. 2015; : e0124653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reimer C, Sondergaard B, Hilsted L, Bytzer P. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. 2009; : 80–87 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason J, Hungin AP. Review article: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the health economic implications. 2005; (Suppl 1): 20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones RH, Lydeard SE, Hobbs FD et al. Dyspepsia in England and Scotland. 1990; : 401–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD et al. Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. 1988; : 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong D. Endoscopic evaluation of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. 1999; : 93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Digital Hospital Episode Statistics England. Primary diagnosis 3: character. http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB30098 (cited December 2017).

- 15.National Institutue for Health and Care Excellence . Clinical Guideline CG184 London: NICE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahrilas PJ, Kim HC, Pandolfino JE. Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. 2008; : 601–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutue for Health and Care Excellence Interventional. Procedures Guidance IPG431 London: NICE; 2012. (now replaced). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velanovich V. Comparison of generic (SF-36) vs. disease-specific (GERD-HRQL) quality-of-life scales for gastroesophageal reflux disease. 1998; : 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zak Y, Rattner DW. The Use of LINX for Gastroesophageal Reflux. 2016; : 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith CD, Ganz RA, Lipham JC et al. Lower esophageal sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease: the safety of a modern implant. 2017; (6): 586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipham JC, Taiganides PA, Louie BE et al. Safety analysis of first 1000 patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease. 2015; : 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harnsberger CR, Broderick RC, Fuchs HF et al. Magnetic lower esophageal sphincter augmentation device removal. 2015; : 984–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipham JC, DeMeester TR, Ganz RA et al. The LINX(R) reflux management system: confirmed safety and efficacy now at 4 years. 2012; : 2,944–2,949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz RA. The esophageal sphincter device for treatment of GERD. 2013; : 661–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czosnyka NM, Buckley FP, Doggett SL et al. Outcomes of magnetic sphincter augmentation: a community hospital perspective. 2017; : 1,019–1,023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]