Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to investigate the combined effects of long working hours and low job control on self-rated health.

Methods:

We analyzed employees’ data obtained from the third Korean Working Conditions Survey (KWCS). Multiple survey logistic analysis and postestimation commands were employed to estimate the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI).

Results:

The odds ratio (OR) for poor self-rated health was 1.24 [95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.13 to 1.35] for long working hours, 1.04 (95% CI: 0.97 to 1.13) for low job control, and 1.47 (95% CI: 1.33 to 1.62) for both long working hours and low job control. The RERI was 0.18 (95% CI: 0.02 to 0.34).

Conclusion:

These results imply that low job control may increase the negative influence of long working hours on self-rated health.

Keywords: job stress, Korean Working Conditions Survey, working hours

Despite a decreasing trend in working hours, Korea exhibits one of the longest average working hours in comparison to other countries.1 There are several reasons underlying the prevalent long working hours in Korea.2 First, Korean society has encouraged long working hours for better economic achievement. Many employees sacrifice their evenings to achieve goals employers or supervisors set, and employees have accepted this. Second, the legal minimum wage is too low to maintain healthy lives. Employees earning near minimal wages working 40 hours a week cannot meet basic needs. For this reason, many employees voluntarily extend working hours to earn more to support their cost of living. Third, as there is widespread job insecurity and poor social protection for the unemployed in Korean society, even those earning a decent income in large companies want to make as much extra income as possible.3

Long working hours might contribute to the rapid economic growth of South Korea, but the negative effects of long working hours, including various health problems, remain a widespread social concern in Korea. An increasing number of studies have reported the association between long working hours and negative health outcomes, including sleep deprivation, depression and anxiety disorders, and cardiovascular diseases, especially stroke.4–14 The relative risk of stroke is 1.33 for those working 55 hours or more than those working 36 to 40 hours (standard working hours).7

In addition to long working hours, social psychological stressors in the workplace may also contribute to poor health.8 Low job control is one of the most well-known occupational stressors. In the job strain model developed by Karasek and Theorell,15 high job strain is defined as the combination of low decision latitude in a task and high psychological demands. High job strain and low job control (low decision latitude, which is one component of job strain) are risk factors for cardiovascular disease and mental health problems such as depression.16–20

Long working hours are linked with insufficient recovery due to reduced sleep hours and rest times.21,22 Furthermore, long working hours are associated with extended exposure to hazardous working conditions. For this reason, the influence of long working hours should be investigated in the context of other working conditions, including occupational stressors. Recently, several studies have explored the interaction between long working hours and other work stressors. A study in Japan reported the harmful effects of overtime work under low job control,23 while a study in Korea showed that long working hours under precarious employment can lead to more severe mental health problems.24 However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have explored these interactions as the main purpose of the study, given that epidemiologists have recently suggested the method for interaction analysis.25 If greater health problems arise due to interactions between long working hours and low job control, an important point for intervention may be to reduce the working hours of workers who are simultaneously exposed to long working hours and low job control.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyze the interaction between long working hours and low job control, and their effect on employees’ health with the sample from third Korean Working Condition Survey (KWCS).

METHODS

Study Subjects

This study used the sample from the third KWCS carried out in 2011 by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA). The KWCS is conducted to assess the distribution of risk factors related to working conditions for occupational safety and health policy, and is comparable to the European Working Conditions Survey. The KWCS provides a nationally representative sample, including the economically active population over 15 years of age. To exclude the influence of underemployment, we included only employees who worked 36 hours or more per week. The total sample size of the third KWCS was 50,033 (unweighted sample size = 50,032). The sample size of employees was 35,903 (unweighted sample size = 29,711), and the sample size of employees with weekly working hours of more than 35 hours was 32,857 (unweighted sample size = 27,039).

Sampling, the Questionnaire, and Survey Weighting

The survey, which involved face-to-face interviews, was conducted by trained interviewers in 2011. The survey sample was drawn from the population and housing census conducted in 2010. In order to ensure a representative sample of the economically active population aged over 15 years, unemployed people, retired persons, housewives, and full-time students were excluded from the survey sample.

Sampling was based on a two-stage stratified approach using the probability-proportional-to-size method, by which census districts were selected based on the number of households in the census district. Then, 10 households were randomly selected within each selected census district. Finally, one eligible person from each selected household was interviewed. When more than one eligible person was identified in a selected household, interviewee selection was randomized using the randomization program on portable computers.

Survey weighting was conducted for the representativeness of the entire economically active population of Korea and was estimated by distribution, region, locality, size, sex, age, and occupation. The response rate of households was considered as well.

Ethical Considerations

The need for ethical review and informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of Hallym University Hospital.

Study Variables

Questionnaire of the 3rd KWCS

All study variables were assessed by the questionnaire. For comparability, the questionnaire was developed based on a translation of the questionnaire for the European Working Conditions Survey. Although validation was not conducted for the third KWCS, the validity and reliability of second KWCS have been reported.26 Regarding working conditions, the second and third KWCSs employed almost the same questions.

Sociodemographic and Behavioral Characteristics

Information about age, sex, education level, income, smoking, and alcohol consumption was collected via interviews. Age was categorized as 15 to 29, 30 to 44, 45 to 55, and 60 or more years. Education level was categorized as middle school (lower secondary education) or less, high school (higher secondary education), or college or more (post-secondary education, tertiary education, or more). Monthly income was divided into quartiles. Alcohol consumption was categorized as none, moderate, or risky. Risky alcohol consumption was defined as drinking more than 7 units of alcohol at one time (binge drinking) or drinking more than 14 units of alcohol per week. Smoking was categorized as nonsmokers, ex-smokers, or current smokers.

Occupational Characteristics

Occupations was categorized as management and professional, office work, sales and service, or manual. A small number of employees in farming and fishery (weighted count: 86) were regarded as manual. Employment status was categorized as regular, temporary, or daily. (Daily labor refers to work based on a daily contract; in Korea, there is a relatively high proportion of daily workers in construction. In general, daily workers face a very unstable employment status.) Shift work was divided into two groups based on the response to the item, “I perform shift work.”

Working Hours and Low Job Control

Working hours were calculated by adding the average number of weekly working hours of the main paid job and the second paid job. Working hours were divided into two categories: 36 to 52 hours per week was considered standard, and more than 52 hours per week was considered long. The legal number of working hours per week in Korea is 40, and 52 hours is the maximum allowed when employees agree to work extended hours. Low job control was defined based on the response to the questionnaire item, “You can influence decisions that are important for your work.” Answers of “rarely” or “never” were regarded as low job control, while “always,” “most of the time,” or “sometimes” were regarded as high job control.

Self-rated Health

Health was assessed based on the response to the subjective question, “How is your health in general?” “Very poor,” “poor,” or “fair” were regarded as self-rated poor health, while “very good” or “good” were regarded as good health.

Other Health Variables

The third KWCS considered medical histories of hypertension and obesity using the questions, “Have you been diagnosed with hypertension by a physician?” and “Have you been diagnosed with obesity by a physician?” However, a medical history of other chronic diseases was not investigated.

Statistical Analysis

A Chi-square test with survey weighting (svy: tab) was used to estimate differences among groups based on long working hours and job control. To estimate odds ratios (ORs), multiple survey logistic analysis was employed [svy: logistic (for adjusted ORs)]. In the model, age, sex, educational level, income, occupation, smoking, and alcohol consumption were included as potential confounders.

For the interaction analysis, we initially employed multiple survey logistic analysis including all other potential confounding variables and the product term between long working hours and low job control in the model. Then, we estimated the combined effect of long working hours and low job control using the linear combination (lincom) command. Finally, we conducted interaction analysis between long working hours and low job control using “linear combination of coefficients” (lincom) and “nonlinear combination of coefficients” (nlcom). RERI and confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the nonlinear combination of coefficients, and the ratio of ORs and CIs were estimated using the linear combination of coefficients. The commands “lincom” and “nlcom” are post-estimation commands for estimating the combined effects of multiple variables after regression-based models. These commands can perform interaction analysis based on both additive and multiplicative scales, and can estimate CIs. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, Texas).

Relative Excess Risk Due to Interaction (RERI) and Ratios of Odds Ratios (ORs)

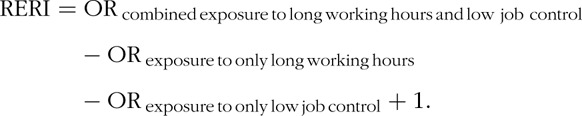

RERI can be used to estimate the interaction between two combined exposures based on an additive scale, calculated using the following formula27:

|

RERI greater than 0 indicates supra-additivity with positive interaction on the additive scale.

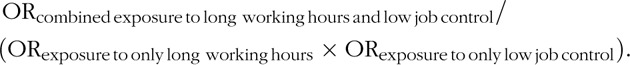

Ratios of ORs estimate the interaction between two combined exposures based on a multiplicative scale and are calculated using the following formula:

|

A ratio greater than 1 indicates that the combined effect of two exposures is greater than the product of the estimated effect of two separate exposures.

RESULTS

Working Hours Based on Sociodemographic and Work Characteristics

A significant proportion of employees in Korea (0.29) worked more than 52 hours per week (Table 1). Men tended to work longer hours than women, and older employees had the highest proportion of long working hours. Regarding socioeconomic status (SES), employees with the lowest education level, with low and middle income, in the service and sales sector, and with temporary contracts had the highest proportion of long working hours. Regarding occupation, the proportion of service and sales workers who worked more than 52 hours per week was 0.42. Regarding work characteristics, shift workers and employees with low job control had a higher proportion of long working hours. Furthermore, unfavorable health behaviors were related to long working hours. In addition, the proportion of current smokers who worked more than 52 hours per week was 0.34, and the proportion of risky alcohol consumers who worked more than 52 hours per week was 0.33.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population by Working Hours

| Total | Long Working Hours (−) | Long Working Hours (+) | |||||

| N | Proportion | N | Proportion | N | Proportion | P* | |

| Gender | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Female | 12,667 | 0.39 | 9392 | 0.74 | 3265 | 0.26 | |

| Male | 20,200 | 0.61 | 13898 | 0.69 | 6302 | 0.31 | |

| Age, years | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 15–29 | 4,972 | 0.15 | 3,361 | 0.68 | 1,612 | 0.32 | |

| 30–44 | 15,841 | 0.48 | 11,619 | 0.73 | 4,221 | 0.27 | |

| 45–59 | 10,003 | 0.30 | 7,087 | 0.71 | 2,916 | 0.29 | |

| 60- | 2,041 | 0.06 | 1,224 | 0.60 | 818 | 0.40 | |

| Smoker | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 17,370 | 0.52 | 13,000 | 0.75 | 4,370 | 0.25 | |

| Ex | 3,789 | 0.11 | 2,608 | 0.69 | 1,181 | 0.31 | |

| Current | 11,698 | 0.35 | 7,682 | 0.66 | 4,016 | 0.34 | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 6,857 | 0.21 | 5,116 | 0.75 | 1,741 | 0.25 | |

| Moderate | 16,337 | 0.50 | 11,669 | 0.71 | 4,668 | 0.29 | |

| Risky | 9,663 | 0.29 | 6,505 | 0.67 | 3,158 | 0.33 | |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Middle school | 2,887 | 0.09 | 1,710 | 0.59 | 1,178 | 0.41 | |

| High school | 11,904 | 0.36 | 7,203 | 0.61 | 4,701 | 0.39 | |

| College or more | 18,064 | 0.55 | 14,378 | 0.80 | 3,687 | 0.20 | |

| Occupation | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Professional and managerial | 2,820 | 0.08 | 2,442 | 0.87 | 379 | 0.13 | |

| Office | 10,440 | 0.32 | 9,187 | 0.88 | 1,253 | 0.12 | |

| Sale and service | 8,779 | 0.27 | 5,049 | 0.58 | 3,731 | 0.42 | |

| Manual | 10,817 | 0.33 | 6,613 | 0.61 | 4,204 | 0.39 | |

| Employment | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Regular | 27,635 | 0.84 | 20,112 | 0.73 | 7,523 | 0.27 | |

| Temporary | 3,788 | 0.12 | 2,218 | 0.59 | 1,570 | 0.41 | |

| Daily | 1,434 | 0.04 | 960 | 0.67 | 474 | 0.33 | |

| Income | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Lowest | 5,536 | 0.17 | 3,736 | 0.67 | 1,801 | 0.33 | |

| Low middle | 8,918 | 0.28 | 5,591 | 0.63 | 3,328 | 0.37 | |

| High middle | 9,017 | 0.28 | 6,356 | 0.70 | 2,662 | 0.30 | |

| Highest | 8,717 | 0.27 | 7,070 | 0.81 | 1,648 | 0.19 | |

| Shift work | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 29,706 | 0.90 | 21,568 | 0.73 | 8,139 | 0.27 | |

| Yes | 3,151 | 0.10 | 1,723 | 0.55 | 1,429 | 0.45 | |

| Job control | <0.0001 | ||||||

| High job control | 20,830 | 0.63 | 15,109 | 0.73 | 5,722 | 0.27 | |

| Low job control | 12,027 | 0.37 | 8,181 | 0.68 | 3,846 | 0.32 | |

Long working hours (−): within the legal limit: 36 ≤ working hours ≤ 52.

Long working hours (+): more than the legal limit: 52 < working hours.

*P values estimated by survey-weighted Chi-square test.

Proportion of Poor Self-Rated Health, and Factors Related to Poor Self-Rated Health

The proportion of poor self-rated health was 0.28 (9,276/32,857), and the proportion of low job control was 0.37 (12,027/32,857).

Table 2 summarizes the factors associated with poor self-rated health without considering the interaction between long working hours and low job control. Long working hours (OR: 1.30, 95% 95% CI: 1.22 to 1.40) and low job control (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.16) were associated with lower self-rated health. Temporary (OR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.10 to 1.32) or daily (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.43 to 1.90) employment status had lower self-rated health relative to regular employment. Regarding education level, those with a middle school education or less (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.22 to 1.58) had a higher risk of poor self-rated health than college graduates. Long working hours, low job control, temporary employment, daily employment, low educational level (middle school or less), and moderate alcohol consumption were significantly statistically associated with poor self-rated health. However, there were no statistically significant associations between occupation, income, smoking, or sex and poor self-rated health.

TABLE 2.

Factors Associated With Poor Self-Rated Health by Multiple Survey Logistic Analysis

| OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Working hours | ||||

| ≤52 hours and >35 | reference | |||

| >52 hours | 1.30 | 1.22 | 1.40 | <0.001 |

| Job control | ||||

| High job control | reference | |||

| Low job control | 1.09 | 1.02 | 1.16 | 0.007 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Professional and managerial | reference | |||

| Office | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.10 | 0.619 |

| Sales and service | 0.99 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 0.900 |

| Manual | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.24 | 0.259 |

| Employment | ||||

| Regular | reference | |||

| Temporary | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.32 | <0.001 |

| Daily | 1.65 | 1.43 | 1.90 | <0.001 |

| Shift work | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 0.852 |

| Income | ||||

| Highest | reference | |||

| High middle | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 0.825 |

| Low middle | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 0.336 |

| Lowest | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.20 | 0.285 |

| Education | ||||

| College or more | reference | |||

| High school | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.11 | 0.417 |

| Middle school or less | 1.39 | 1.22 | 1.58 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Ex- | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 0.082 |

| Current | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.291 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Moderate | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 0.011 |

| Risky | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.11 | 0.793 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | reference | |||

| Female | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 0.432 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 15–29 | reference | |||

| 30–44 | 1.45 | 1.31 | 1.59 | <0.001 |

| 45–59 | 2.03 | 1.83 | 2.26 | <0.001 |

| 60+ | 2.61 | 2.24 | 3.05 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Interaction Analysis using Post-Estimation Command (Linear Combination of Coefficients and Nonlinear Combination of Coefficients)

When employees worked long hours without low decision latitude, the OR for self-rated health was 1.24 (95% CI: 1.13 to 1.35). The OR for poor self-rated health was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.97 to 1.13) when employees worked under low job control without long working hours. Moreover, when employees were simultaneously exposed to long working hours and low job control, the OR for poor self-rated health was 1.47 (95% CI: 1.33 to 1.62). RERI (indicating additive interaction) was 0.18 (95% CI: 0.02 to 0.34). The ratio of ORs (indicating multiplicative interaction) was 1.13 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.28), with a P value of 0.06 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effect of Long Working Hours and Low Job Control on Self-Rated Health∗

| Long Working Hours (−) | Long Working Hours (+) | OR for Long Working Hours (−) versus Long Working Hours (+) Within Strata of Job Control | |

| OR (95% CI): P | OR (95% CI): P | OR (95% CI): P | |

| High job control | reference | 1.24 (1.13–1.35): <0.001 | 1.24 (1.13–1.35): <0.001 |

| Low job control | 1.04 (0.97–1.13): 0.252 | 1.47 (1.33–1.62): <0.001 | 1.40 (1.27–1.55): <0.000 |

| OR for low job control (0) versus low job control (1) Within strata of long working hours | 1.04 (0.97–1.13): 0.252 | 1.18 (1.06–1.31): <0.001 | |

| Measure of interaction on additive scale: RERI | 0.18 (0.02–0.34): 0.027 | ||

| Measure of interaction on multiplicative scale: ratio of ORs | 1.13 (0.99–1.28): 0.061 |

Long working hours (−): within the legal limit: 36 ≤ working hours ≤ 52.

Long working hours (+): more than the legal limit: 52 < working hours.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction.

*The model was adjusted for age, sex, education, income, occupation, smoking, and alcohol consumption. ORs and ratios of ORs were estimated using the linear combination command, and RERI was estimated using the nonlinear combination command after multiple survey logistic analysis (linear combination and nonlinear combination are post-estimation commands for the combination of effects in Stata).

Additional Analysis Including Hypertension and Obesity in the Model

In Table 3, age, sex, income, education, occupation, income, smoking, and alcohol consumption are included as potential confounders. A medical history of hypertension or obesity was additionally included in the model. Although hypertension (OR: 1.88; 95% CI: 1.63 to 2.17) and obesity (OR: 1.97; 95% CI: 1.62 to 2.42) increased the risk of poor self-rated health, the statistical significance of long working hours and low job control on self-rated health did not change. When hypertension and obesity were included in the model, the OR for poor self-rated health with long working hours was 1.24 (95% CI: 1.13–1.35), while the OR for poor self-rated health with low job control was 1.05 (95% CI: 0.97–1.14). Further, RERI was 0.19 (95% CI: 0.03–0.35) and the ratio of ORs was 1.14 (95% CI: 0.99–1.29) when hypertension and obesity were included.

DISCUSSION

Interaction Between Long Working Hours and Low Job Control

Longer working hours can result in longer exposure to harmful working conditions. The interaction between long working hours and job stressors could have a synergistic detrimental effect on health. Measuring interactions on an additive scale is the most appropriate way to assess interaction in modern epidemiologic studies.27,28 The current study investigated the interaction between long working hours and low job control. RERI due to combined exposure to long working hours and low job control was greater than 0, indicating that the effect of joint exposure was greater than the additive effect of both exposures. Thus, although the size of the effect was moderate, there was synergism between concurrent exposure to long working hours and low job control.

Although no previous study has reported the interaction between long working hours and other psychosocial stressors based on an additive scale, several studies have suggested that there could be an interaction between long working hours and psychosocial working conditions. A study among British civil servants reported that the OR between long working hours and major depressive disorders increased when SES and job stressors were adjusted.13 That study did not directly investigate the subpopulation among British civil servants that worked long hours. However, another study of the same population found that higher-level civil servants—usually associated with high job control—tended to work long hours.12 The results suggested that a higher grade and high job control might reduce the detrimental effects of long working hours on mental health.

Another study reported that the incidence of type II diabetes mellitus increased among individuals with low SES, although long working hours were not associated with such an increase among all participants.29 These results suggest that high job control and higher social position might ameliorate the harmful influence of long working hours. Conversely, long working hours might be more harmful under unfavorable psychosocial working conditions due to higher exposure to adverse conditions. By contrast, in Korea, a significant proportion of employees with low SES worked long hours, as summarized in Table 1. This phenomenon could imply that workers with low SES have to work long hours to meet basic needs and to compensate for low hourly wages. Similarly, in another Korean study, simultaneous exposure to both long working hours and precarious employment had a greater effect on depression than exposure to just one or the other (although that study did not include an interaction analysis based on the additive scale).24 These results might reflect the heavy burdens (simultaneous exposure to long working hours and low job control) borne by Korean employees with low SES.

To explore the interaction between SES and long working hours, an additional interaction analysis—which included gender, age, employment status, income, smoking, alcohol consumption, and shift work as covariates—was conducted for the same population. We did not find a significant interaction between educational level and long working hours on the additive scale (RERI: 0.15; 95% CI: 0.08–0.32; P = 0.062). Moreover, it is unclear whether an interaction exists between long working hours and low job control in other populations. To enhance external validity, an additional analysis using a similar survey among different populations (eg, European workers) should be conducted in the future.

Suggestion for Strict Regulation of More than 52 Working Hours a Week

With the introduction of the 5-day work week in 2002, the Labor Standards Act limited weekly working hours to 52 hours with the employee's consent. The legal limit for working hours has been a controversial issue in Korea.30 The Korean government, especially the Department of Employment and Labor, has not regarded working more than 52 hours as illegal, as working an additional 16 hours on the weekend is excluded from the calculation. On the basis of this interpretation of the Labor Standards Act, employers have been able to encourage employees to work additional hours on the weekend without violating the law. However, the courts have changed their opinion regarding limits on weekly working hours. There is some judicial precedent that additional weekend hours should be included in weekly working hours.30–32 Accordingly, the debate concerning limits on weekly working hours requires a sociopolitical solution.33 The findings of the present study suggest that more strict regulations on working hours should be implemented. In particular, strict regulation on working hours to not exceed 52 hours per week could significantly improve the health of vulnerable subpopulations (eg, employees with low job control, which is generally related to low SES).

Study Limitations

Although this study used a large, nationally representative sample, it has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study could not establish a causal relationship between exposure and health outcomes. As employees tend to reduce working hours when they are sick, poor self-rated health might not lead to long working hours. Thus, the possibility of reverse causation between poor self-rated health and long working hours might be low. It is also possible that poor self-rated health could contribute to the perception of low job control. Given the nature of cross-sectional study, we cannot exclude the possibility of reverse causation. However, the results of the present study are consistent with the results of other cohort studies that reported low job control and adverse health outcomes.17,18,34

Second, the measurement of working hours and health status was subjective and could be subject to information bias. In particular, self-rated health is a subjective measurement of health status. However, previous research, including a prospective cohort study, has consistently reported that poor self-rated health is linked with objective health outcomes, such as mortality.35–37 Even after adjusting for other health-related covariates, self-rated health could predict future mortality.

Third, the validity and reliability of the questionnaires used for the third KWCS were not estimated, although a previous study reported that the second KWCS survey was valid and reliable.

Finally, we assessed job control using a single question related to decision authority. Thus, this single question might not capture other aspects of job control, especially skill discretion, which is another component of low job control. Although the reliability of this single question might be debatable, the authors believe this question arguably measures one of the most important aspects of job control.

CONCLUSION

This study's findings suggest a need to adjust policies regarding working hours. Long working hours under stressful working conditions might have a synergistic negative effect on health. In particular, the health of a vulnerable subpopulation (workers with low job control) might be significantly improved by reducing the number of working hours. In addition, the health of the average population might be improved by reducing the working hours of those who work more than 52 hours (the legal limit) in Korea. Along with strict regulations on working hours, the minimum wage should be increased to support healthy living conditions for those who work the standard number of hours.38 Moreover, social protection programs for the unemployed should be improved.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (OSHRI) and the KOSHA for providing the raw data from the KWCS.

Footnotes

The need for ethical review and informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of the Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital (Approval number: 2017-I050).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Average Annual Working Time 2013/1. OECD; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae KS. What sustains the working time regime of long hours in South Korea? 2012; 95:128–162. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung EH. Employment stability in Korea in comparative perspective. 2014; 103:103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artazcoz L, Cortès I, Escribà-Agüir V, Cascant L, Villegas R. Understanding the relationship of long working hours with health status and health-related behaviours. 2009; 63:521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. 2014; 40:5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim BH, Lee HE. The association between working hours and sleep disturbances according to occupation and gender. 2015; 32:1109–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivimäki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. 2015; 386:1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nixon AE, Mazzola JJ, Bauer J, Krueger JR, Spector PE. Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. 2011; 25:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakashima M, Morikawa Y, Sakurai M, et al. Association between long working hours and sleep problems in white-collar workers. 2011; 20:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shields M. Long working hours and health. 1999; 11:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Gimeno D, et al. Long working hours and sleep disturbances: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. 2009; 32:737–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. 2011; 41:2485–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virtanen M, Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M. Overtime work as a predictor of major depressive episode: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. 2012; 7:e30719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim I, Kim H, Lim S, et al. Working hours and depressive symptomatology among full-time employees: results from the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2013; 39:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karasek R, Theorell T. Theorell T, Karasek RS. The psychosocial environment. . New York: Basic Books; 1992. 31–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot MG, Bosma H, Hemingway H, Brunner E, Stansfeld S. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. 1997; 350:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. 2006; 32:443–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. 2015; 15:738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosma H, Marmot MG, Hemingway H, Nicholson AC, Brunner E, Stansfeld SA. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. 1997; 314:558–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. 1992; New York: Basic Books, 338. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Härmä M. Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. 2006; 32:502–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Hulst M. Long workhours and health. 2003; 29:171–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hino A, Inoue A, Kawakami N, et al. Buffering effects of job resources on the association of overtime work hours with psychological distress in Japanese white-collar workers. 2015; 88:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim W, Park EC, Lee TH, Kim TH. Effect of working hours and precarious employment on depressive symptoms in South Korean employees: a longitudinal study. 2016; 73:816–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. 2012; 41:514–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim YS, Rhee KY, Oh MJ, Park J. The validity and reliability of the second Korean working conditions survey. 2013; 4:111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderWeele TJ, Knol MJ. A tutorial on interaction. 2014; 3:33–72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Walker AM. Concepts of interaction. 1980; 112:467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Kawachi I, et al. Long working hours, socioeconomic status, and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of published and unpublished data from 222 120 individuals. 2015; 3:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park EJ. Extended work and holiday work. 2014; 51:261–288. (in Korean). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han IS. Debate on weekend working. 2014; 8:46–60. (in Korean). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HY. Weekend working hours should be included in weekly working hours. 2012; 42:354–358. (in Korean). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bae KS. Long working hours and reducing working hours in South Korea. 2013; 10:7–18. (in Korean). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonde JP. Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. 2008; 65:438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mavaddat N, Parker RA, Sanderson S, Mant J, Kinmonth AL. Relationship of self-rated health with fatal and non-fatal outcomes in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2014; 9:e103509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen C, Schooling CM, Chan WM, et al. Self-rated health and mortality in a prospective Chinese elderly cohort study in Hong Kong. 2014; 67:112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. 2009; 69:307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris J, Donkin A, Wonderling D, Wilkinson P, Dowler E. A minimum income for healthy living. 2000; 54:885–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]