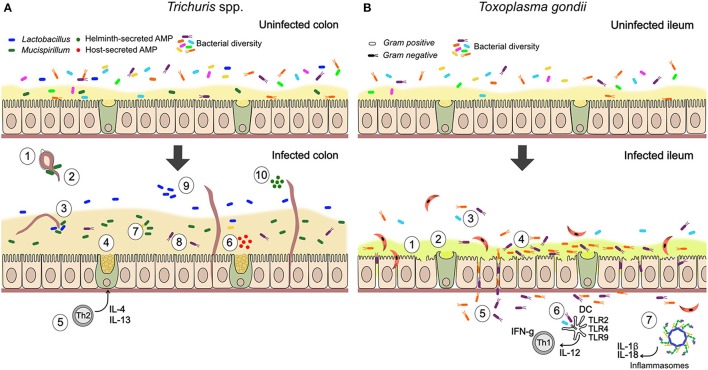

Figure 1.

Summary of documented mechanisms by which infection with Trichuris spp. and Toxoplasma gondii may alter the gut microbiota. (A) In Trichuris infection, parasites stimulate an anti-inflammatory mucogenic immune response that may improve barrier function and reduce bacterial-driven inflammation. Direct interactions through physical attachment and secreted molecules are also likely. (1) Gut bacteria attach to polar caps and allow egg-hatching (Hayes et al., 2010). (2) T. muris-induced changes to the gut microbiota inhibit hatching of further T. muris eggs (White et al., 2018). (3) T. muris can ingest bacteria from their environment (White et al., 2018). (4) Mucin expression changes from MUC2 to MUC5AC, altering physical properties of the mucus (Hasnain et al., 2013). (5) Trichuris drives a Th2-mediated mucogenic response, leading to goblet cell hyperplasia and increase in mucus volume (Broadhurst et al., 2010, 2012). (6) Infection induces production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) by goblet cells (e.g., Ang4; D'Elia et al., 2009). (7) Infection drives expansion of Mucispirillum, a mucolytic genus of bacteria (Wu et al., 2012; Holm et al., 2015; Houlden et al., 2015). (8) Mucus can reduce adherence of bacteria to the epithelium, in the context of inflammatory disease (Broadhurst et al., 2012). (9) Infection drives expansion of Lactobacillus and other changes in community structure, including reduced microbial diversity (Holm et al., 2015; Houlden et al., 2015). (10) Helminths directly secrete AMPs in excretory-secretory products (Abner et al., 2001). (B) During T. gondii infection, inflammatory processes play an important role in parasite-microbiota interactions and their consequences. Degradation of barrier function by parasites allows bacterial translocation and consequent inflammation, while microbe-driven pro-inflammatory responses contribute to anti-parasite immunity. (1) Blunted villi and epithelial damage (Cohen and Denkers, 2014; Trevizan et al., 2016). (2) Change to more acidic and neutral mucins, thought to increase mucus fluidity (Trevizan et al., 2016). (3) Reduction in bacterial diversity (Heimesaat et al., 2006). (4) Increase in adherent Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli and Bacteroides/Prevotella) relative to Gram-positive (Heimesaat et al., 2006). (5) Bacterial translocation to lamina propria (Heimesaat et al., 2006; Hand et al., 2012; Cohen and Denkers, 2014). (6) Stimulation of protective pro-inflammatory immune response against parasites by bacterial TLR stimulation (Benson et al., 2009). With high dose infection, inflammatory disease (ileitis) results from a cytokine storm (Hand et al., 2012). (7) T. gondii infection activates NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes (Ewald et al., 2014; Gorfu et al., 2014), driving production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-18 and IL-1β, that mediate resistance to the parasite but are expected to also affect gut microbes.