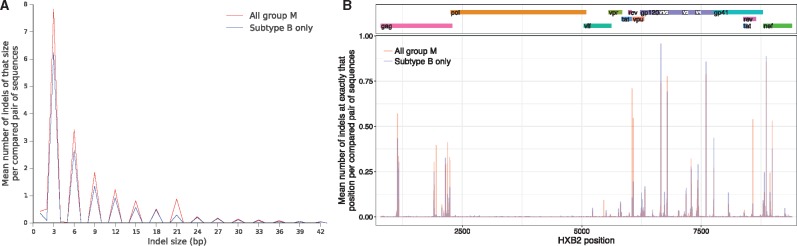

Figure 3.

Quantifying indels in 3,249 whole genomes—those in the 2016 ‘all genome’ group M alignment from the Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV database. We trimmed both 3’ and 5’ ends of the alignment where sequences align poorly, then considered each of the roughly 5.3 million possible pairs of references therein. For each pair we calculated the size and position of their relative indels (i.e. taking their relative alignment from the overall alignment, ignoring positions at which both have a gap). We also considered just the subset of 1,019 subtype B sequences, which is less diverse than group M as a whole but shows similar indel patterns. Left panel: the distribution of indel sizes. The striking bias towards frame-preserving indels could be biological (frame-shifting indels will generally have a large fitness cost), artefactual (removal of frame-shifting indels from sequences during analysis before public release, on the assumption that this is sequencing or bioinformatic error), or a combination of both. Right panel: where in the genome the indels tend to occur. The observed pattern is consistent with purifying selection in pol and diversifying selection in env.