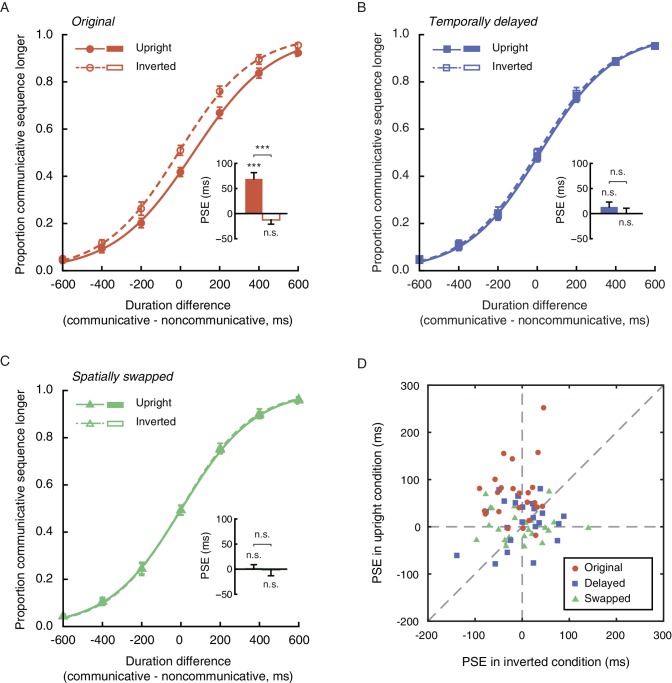

Figure 2. Perception of social interaction shortens subjective duration.

(A) Proportion of responses in which observers reported a communicative motion sequence as longer in duration than a noncommunicative one, plotted as a function of the physical duration difference between the two. Data are shown for the upright (solid curve) and the inverted (dashed curve) conditions in Experiment 1. Inset shows the PSEs. A PSE of 0 indicates a consistency between subjective duration and physical duration. (B-C) Psychometric functions for Experiments 2 and 3 where a temporally delayed version (B) and a spatially swapped version (C) of the motion sequences in Experiment 1 were respectively used. In both cases, the strengths of the spatial-temporal correlations between acting agents were unaltered but the communicative intentions were disrupted. (D) The PSEs for the upright condition versus the PSEs for the inverted condition for individual observers in Experiments 1 (red dots), 2 (blue squares) and 3 (lime triangles). A slope of 1 (dashed diagonal line) represents comparable PSEs for the upright and the inverted conditions. Error bars: standard errors of the mean; ***p<0.001.