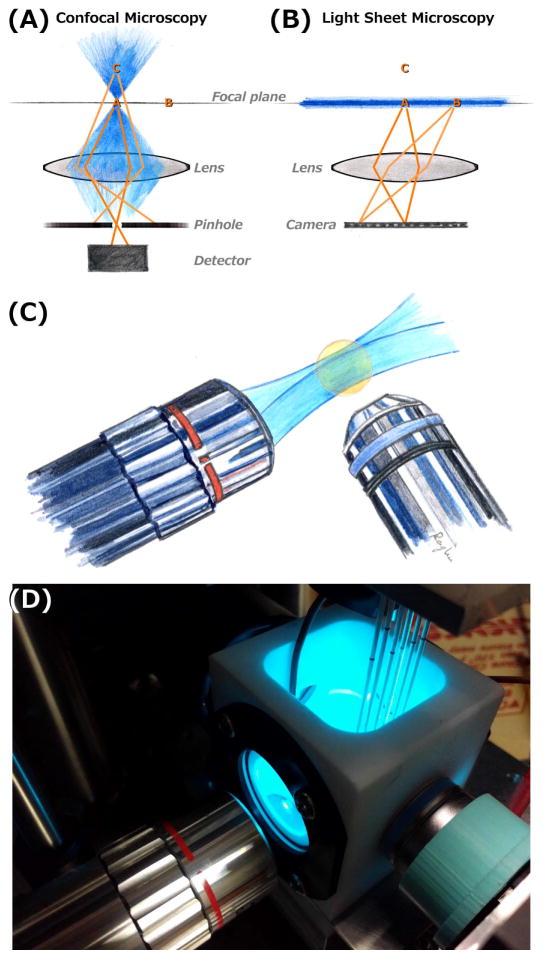

Figure 1.

(A,B) Schematic illustrations of confocal (A) and light sheet fluorescence (B) microscopies. Excitation light is shown in blue, focused to a point in confocal imaging and shaped into a sheet in light sheet imaging. In each diagram, points A and B lie in the objective lens focal plane, and C is outside the plane. In confocal microscopy, fluorophores outside the focal point are excited, but their emission light is blocked by a confocal pinhole. At any instant, information is collected from only a single point (point A), and three-dimensional images are formed by scanning across all three dimensions. In light sheet microscopy, only fluorophores in the focal plane are excited, and their emission is mapped onto a camera. This provides an image of the entire plane at any instant, and enables three-dimensional imaging by scanning in the one perpendicular direction. (C) Schematic illustration of a typical lens geometry for light sheet fluorescence microscopy. The excitation sheet (blue) is provided by one lens, and emission from its intersection with a specimen (orange) is detected by a perpendicular lens. (D) A photograph of one of the home-built light sheet fluorescence microscopes in the author’s laboratory. The excitation and detection lenses are oriented as in (C). Specimens, in this case larval zebrafish, are mounted in agar gels extruded from glass capillaries, held from above by a computer-controlled stage. The specimens, and the end of the detection lens, are immersed in a temperature-controlled bath.