Abstract

At abnormally elevated levels of intracellular Ca2+, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake may compromise mitochondrial electron transport activities and trigger membrane permeability changes that allow for release of cytochrome c and other mitochondrial apoptotic proteins into the cytosol. In this study, a clinically relevant canine cardiac arrest model was used to assess the effects of global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake capacity, Ca2+ uptake-mediated inhibition of respiration, and Ca2+-induced cytochrome c release, as measured in vitro in a K+-based medium in the presence of Mg2+, ATP, and NADH-linked oxidizable substrates. Maximum Ca2+ uptake by frontal cortex mitochondria was significantly lower following 10 min cardiac arrest compared to non-ischemic controls. Mitochondria from ischemic brains were also more sensitive to the respiratory inhibition associated with accumulation of large levels of Ca2+. Cytochrome c was released from brain mitochondria in vitro in a Ca2+-dose-dependent manner and was more pronounced following both 10 min of ischemia alone and following 24 h reperfusion, in comparison to mitochondria from non-ischemic Shams. These effects of ischemia and reperfusion on brain mitochondria could compromise intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, decrease aerobic and increase anaerobic cerebral energy metabolism, and potentiate the cytochrome c-dependent induction of apoptosis, when re-oxygenated mitochondria are exposed to abnormally high levels of intracellular Ca2+.

Keywords: Hippocampus, Cortex, Respiration, Apoptosis, Excitotoxicity

1. Introduction

Substantial evidence obtained from neuronal culture models of excitotoxicity indicates that mitochondria are a primary initial target of injury caused by the elevated influx of Ca2+ that occurs following excessive activation of ionotropic receptors for excitatory amino acids, e.g., glutamate. Although respiration-dependent mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation plays a role in buffering cytosolic Ca2+ levels during activation of these receptors (White and Reynolds, 1995; Wang and Thayer, 1996; Rueda et al., 2016), excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration can lead to either apoptosis or necrosis, depending on the extent of the excitotoxic insult (Dugan et al., 1995; Ankarcrona et al., 1995; Budd and Nicholls, 1996; Castilho et al., 1999; Niquet et al., 2006). The mechanisms by which Ca2+-injured mitochondria lead to cell death include failure to maintain adequate levels of cellular ATP, generation of reactive oxygen species, and the release of mitochondrial proteins that can activate the cascade of events leading to apoptosis (Thornton and Hagberg, 2015; Cali et al., 2012; Perez-Pinzon et al., 2012; Polster and Fiskum, 2004). Involvement of these mechanisms in neuronal death following cerebral ischemia and reperfusion is due to the extremely high levels of extracellular excitotoxic neurotransmitters and the supranormal levels of intracellular Ca2+ that exist within a few minutes following the onset of complete ischemia (Silver and Erecinska, 1990).

The contribution of apoptosis to delayed neuronal death following cerebral ischemia is well established (Krajewska et al., 2004; Hagberg et al., 2009). Evidence obtained from a variety of in vitro and in vivo apoptotic cell death paradigms indicates that the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol is one mechanism by which the cascade of cell death proteases (caspases) is activated (Ow et al., 2008; Broughton et al., 2009). Such activation leads to chromatin condensation, nucleosomal DNA fragmentation, and formation of apoptotic cell bodies. Loss of cytochrome c from mitochondria may also promote mitochondrial free radical production and the increase in the generation of reactive oxygen species that often accompanies the induction of apoptosis (Cai et al., 1998; Franklin, 2011). Release of cytochrome c is inhibited by the anti-apoptosis gene product Bcl-2 (Kluck et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1997; Polster et al., 2001), which has also been shown to protect against ischemic and hypoxic neural cell apoptosis (Martinou et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1995; Krajewski et al., 1995; Myers et al., 1995; DeVries et al., 2001), and to protect neural cell mitochondria against both Ca2+ and oxidative stress-mediated respiratory injury (Murphy et al., 1996a, 1996b; Kowaltowski and Fiskum, 2005).

Cytochrome c is a 12.5 kDa component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain that is normally entrapped between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes and interacts loosely with other electron transport components in the inner membrane through electrostatic interactions (Matlib and O’Brien, 1976; Cortese et al., 1995). However, when mitochondria are exposed in vitro to conditions that result in osmotic swelling and an increase in the matrix volume, cytochrome c can be released into the surrounding milieu due to rupture of the outer membrane (Chappell and Crofts, 1965). Release of cytochrome c and other proteins by this mechanism under conditions that include the presence of exogenous Ca2+ has been interpreted to be due to high amplitude swelling due to activation of a mitochondrial inner membrane permeability transition pore (PTP) (Pfeiffer et al., 1995; Kantrow and Piantadosi, 1997; Yang and Cortopassi, 1998; Ye et al., 2016; Gustafsson and Gottlieb, 2008). Several laboratories have proposed that the opening of this pore is a critical event in precipitating the release of cytochrome c associated with the induction of apoptosis (Kroemer et al., 1997; Pastorino et al., 1998; Scarlett and Murphy, 1997; Bradham et al., 1998). However, observations made with both cells and isolated brain mitochondria incubated under physiologically realistic conditions suggest that release of cytochrome c can also occur by a more specific increase in permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane that does not necessitate swelling and membrane disruption (Vander Heiden et al., 1997, Bossy-Wetzel et al., 1998; Andreyev et al., 1998; Andreyev and Fiskum, 1999; Zhuang et al., 1998; Polster et al., 2001).

Although mitochondria from different animal cells and tissues share many common biochemical characteristics, different types of mitochondria deviate in the amount of Ca2+ they can actively accumulate and differ in their sensitivity to Ca2+-induced functional alterations (Fiskum and Cockrell, 1985; Murphy et al., 1990; Andreyev and Fiskum, 1999; Toman and Fiskum, 2011). The vulnerability to Ca2+-induced mitochondrial injury may also depend on the structural and functional integrity of the mitochondria. Brain mitochondria are highly sensitive to respiratory dysfunction and membrane lipid alterations caused by ischemia and reperfusion (Fiskum et al., 1999; Wang and Michaelis, 2010), although the effects of these alterations on the responses of mitochondria to elevated levels of ambient Ca2+ has not been adequately addressed. As neuronal mitochondria are exposed to excessively high levels of cytosolic Ca2+ following even brief periods of cerebral ischemia (Silver and Erecinska, 1990), it is quite possible that accumulation of abnormal Ca2+ levels by functionally impaired mitochondria during reperfusion could result in further impairment in cerebral energy metabolism, release of cytochrome c, and elevated production of reactive oxygen species.

The primary objective of the present study was to determine if a relatively short period of global cerebral ischemia in the absence or presence of a prolonged period of reperfusion compromises the ability of brain mitochondria to buffer extramitochondrial Ca2+ under physiologically relevant conditions. Another objective was to determine whether cerebral ischemia, plus or minus reperfusion, alters the vulnerability of mitochondria to Ca2+ induced changes, e.g., respiration and cytochrome c release, that could promote necrotic or apoptotic cell death.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Canine cardiac arrest model of global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion

A well-established canine ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest and resuscitation model was used in this study (Vaagenes et al., 1984; Rosenthal et al., 1987). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the George Washington University School of Medicine, where all experiments were conducted. Adult female beagles weighing 10–15 kg were initially anesthetized with intravenous sodium thiamylal (17.6 mg/kg). Soon thereafter, intravenous chloralose at 37.5 mg/ml was administered and a second dose was given 30 min later. For animals that were used for 24 h experiments, hourly boluses of intravenous morphine sulfate (0.1 mg/kg) were given. Also, antibiotic prophylaxis was provided with 250 mg intravenous ceftriaxone. All animals were intubated, ventilated with 21% O2, and subjected to a left lateral thoracotomy. In this study, 3 groups were used: Sham operated, non-ischemic controls; animals experiencing 10 min cardiac arrest in the absence of resuscitation and; animals that underwent 10 min cardiac arrest, resuscitation, and 24 h of reperfusion under constant critical care. One key variable in this model is the resuscitative ventilatory O2 concentration used following the 10 min electrically induced cardiac arrest (Liu et al., 1998; Balan et al., 2006). In this study 100% O2 was used during 3 min of open-chest manual cardiac massage and following cardiac defibrillation. Approximately 5 min later, when the first arterial blood gas determination was obtained, the ventilatory O2 setting was adjusted and then continuously controlled throughout the 24 h period of reperfusion to maintain arterial pO2 in the normal range of 80 and 120 mm Hg. At the end of each experimental period, a craniotomy was performed and 1–2 g of right frontal cortex was excised and immersed within 5 s in ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer. The right cerebral hemisphere was then removed, the hippocampus and striatum excised and placed in mitochondrial isolation buffer within 30 s of the hemispherectomy. Animals were then euthanized by intra-arterial administration of a pentobarbital-based euthanasia solution.

2.2. Isolation of brain mitochondria

Brain mitochondria from canine frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum were isolated according to a procedure that yields both synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria (Demarest et al., 2016). Brain tissue samples were placed in ice-cold mitochondrial isolation medium containing 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 5 mM Hepes-KOH, 1 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 1 mM EGTA (pH 7.4). Samples were homogenized with a teflon tissue grinder pestle and then centrifuged at 1300 × G for 3 min, resulting in a pellet containing nuclei and tissue debri. The supernatant was centrifuged at 22,000 × G for 8 min, yielding a pellet containing primarily “free”, non-synaptic mitochondria plus synaptic nerve endings (synaptosomes). The pellet was resuspended in isolation medium containing 0.02% digitonin. Digitonin is a steroid glycoside that binds to and forms micelles with cholesterol and cholesterol esters. Digitonin at this very low concentration selectively permeabilizes membranes that contain relatively high levels of cholesterol. Since synaptosomes have high cholesterol, exposure to digitonin releases mitochondria from the synaptic nerve endings without permeabilizing mitochondrial inner or outer membranes. Following 2 min of suspension in the digitonin-containing solution, the suspension was centrifuged again at 22,000 × G for 8 min. A small fraction of the pellet termed the “fluffy layer” was carefully aspirated off the top of the pellet. The pellet was again resuspended in isolation medium not containing digitonin and centrifuged at 22,000 × G for 8 min in a microcentrifuge. The resulting pellet was resuspended in a minimum volume of buffer containing 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), and 1 mg/ml fatty acid free BSA to a protein concentration of approximately 30 mg ml−1, as determined by a modified biuret reaction with BSA as a standard (Skarkowska and Klingenberg, 1963).

2.3. Mitochondrial incubations

Unless stated otherwise, mitochondria were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min in medium containing 125 mM KCl, 2 mM K2HPO4, 5 mM HEPES-KOH, 5 mM glutamate, 5 mM malate, 3 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.0). When mitochondria were exposed to exogenous Ca2+, one or more additions of CaCl2 were made starting 1–2 min following the addition of mitochondria to the media. For measurements of the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, a 1 ml aliquot of the 2 ml suspension was removed following 10 min of incubation and centrifuged at 13,000 × G for 3 min in a micro-centrifuge. A 0.75 ml aliquot of supernatant was carefully removed, supplemented with 30 μl of Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, frozen on dry ice and stored at −70 °C. The pellet was resuspended to the initial 1 ml volume with experimental medium containing protease inhibitors but not oxidizable substrates, ATP or MgCl2, and then rapidly frozen and stored at −70 °C.

2.4. Mitochondrial calcium transport

Calcium fluxes were measured by monitoring the medium free Ca2+ concentration of the 2 ml mitochondrial suspension (0.5 mg protein ml−1) with the fluorescent indicator Calcium Green 5N (0.1 μM), using excitation and emission wavelengths of 506 and 513 nm, respectively. Fluorescence was continually monitored with a Hitachi F-2500 spectrofluorometer equipped with a temperature-regulated cuvette holder (37 °C) and magnetic stirring. The maximum Ca2+ uptake capacity was defined as the sum of the Ca2+ additions that were completely accumulated.

2.5. Mitochondrial respiration

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption was measured polarographically with a Clark-type electrode in a 0.6 ml closed chamber with magnetic stirrer (Yellow Springs Instruments Co.) at a thermostatically controlled temperature of 37 °C. The solubility of oxygen was taken to be 195 μM at 37 °C. The mitochondrial protein concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1 was used for the assay using 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate as substrates. State 3 respiration was measured after addition of 0.4 mM ADP to the same incubation medium that was used for the Ca2+ uptake measurements.

2.6. Western immunoblot measurements of cytochrome c

Frozen mitochondrial samples were thawed on ice and 16 μl aliquots (diluted to 0.1 mg mitochondrial protein ml−1) were run on to 4–20% Tris-Glycine gradient gels under denaturing and reducing conditions. Horse heart cytochrome c was used as a standard and Rainbow Marker was used as molecular weight standard. SDS-PAGE was performed in a Novex chamber at constant current (20 mA per gel) in a cold room until the dye front reached the bottom of the gel. Proteins were electro-transferred to PVDF membranes using a Novex blot module at constant voltage (30 V) for 1.5 h until the transfer of rainbow marker was complete. Gels were coomassi stained to ensure complete transfer of proteins. Membranes were rinsed with tris-buffered saline buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and blocked overnight in TBS-T supplemented with 10% dry milk at 4 °C. Immunodetection of cytochrome c was performed using 7H8 mouse anti-cytochrome c antibody (PharMingen) as primary antibody (1:2000 dilution) and sheep anti-mouse IgG bound to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) as secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution). After thorough washing of the membrane with TBS-T, peroxidase activity was detected using Enhanced Chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham). X-ray film was exposed for different periods obtain band intensities in a range that was determined with purified cytochrome c to be linearly related to the amount of protein. Typically, the antibodies used demonstrated negligible cross-reactivity with either Rainbow marker or mitochondrial bands other than the 12.5 kDa band (cytochrome c). Band intensities were analyzed densitometrically using Storm Imager System (Molecular Dynamics) or GelExpert system (NucleoTech).

2.7. Reagents and materials

Pre-cast gradient gels and PVDF membrane-filter paper sandwiches were from Novex; X-OMAT AR film was from Kodak; Rainbow Marker was from Amersham; mannitol, sucrose, EGTA, MgCl2, ATP, ADP, defatted BSA, cytochrome c, oligomycin, Triton and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail were purchased from Sigma. KCl, KOH, HCl, MgSO4, HEPES and Tris were from Fisher Scientific. Calcium Green 5N was purchased from Molecular Probes.

2.8. Data analysis

One-way ANOVA and the Duncan’s method for multiple pairwise comparisons were used for comparisons of results obtained for three animal groups. The number of animals used in each group (n = 4) was purposely kept to the minimum necessary for statistical analyses due to the use of dogs in this clinically realistic animal model of cardiac arrest and resuscitation.

3. Results

3.1. Calcium uptake by brain mitochondria following cardiac arrest and resuscitation

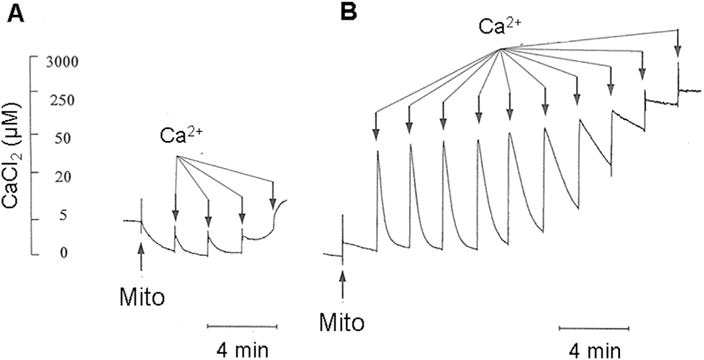

Brain mitochondria have a very limited ability to accumulate calcium ions in the absence of exogenous adenine nucleotides and (or) Mg2+ (Tjioe et al., 1970; Rottenberg and Marbach, 1989). Fig. 1A describes the changes in the medium free Ca2+ that occurred when canine cortex mitochondria isolated from a non-ischemic animal were exposed to multiple additions of CaCl2 in the presence of the NAD-linked oxidizable substrates malate plus glutamate and in the absence of exogenous Mg2+ or adenine nucleotides. These mitochondria accumulated all of the first two additions of 10 nmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein. However, upon addition of a third bolus, essentially no additional Ca2+ was accumulated and the mitochondria started to release the Ca2+ that had been already accumulated. In contrast, under the same conditions but in the presence of 3 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2, mitochondria sequestered seven additions of 300 nmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein for a total of over 2100 nmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein and did not exhibit net release of Ca2+ even when no additional Ca2+ could be sequestered (Fig. 1B). As published earlier (Andreyev et al., 1998) (Andreyev and Fiskum, 1999) in the presence of ATP and Mg2+ the Ca2+ uptake capacity was not affected by the presence of 2.0 μM cyclosporin A, which is a potent inhibitor of PTP opening (not shown).

Fig. 1. Fluorescent measurements of calcium uptake by cerebral cortex mitochondria.

Synaptic plus non-synaptic mitochondria were isolated from non-ischemic frontal cortex and added at a final concentration of 0.5 mg protein ml−1 to a KCl-based medium maintained at 37 °C and containing the respiratory substrates glutamate plus malate and the fluorescent calcium indicator Calcium Green 5N (0.1 μM). Mitochondria calcium uptake was measured by following the increase and subsequent decrease in fluorescence (506 nm excitation and 523 nm emission) upon addition of CaCl2 aliquots. A. Mitochondrial uptake of 10 nmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein aliquots in the absence of either ATP or Mg2+. B. Mitochondrial uptake of 300 nmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein aliquots in the presence of 3 mM ATP and 4 mM Mg2+.

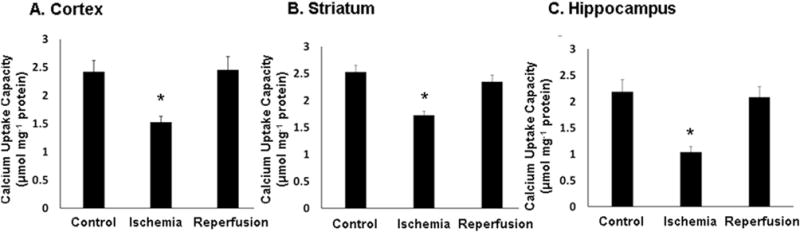

The maximum calcium uptake capacity by brain mitochondria following 10 min cardiac arrest in the absence or presence of 24 h reperfusionwas determined in the presence of both ATP and Mg2+. The mean calcium uptake capacity ± s.e. for mitochondrial preparations from the frontal cortex, hippocampus and striatum from n = 4 non-ischemic control animals, and from animals subjected to ischemia alone (n = 4) or ischemia plus 24 h reperfusion (n = 4) are presented in Fig. 2. The Ca2+ uptake capacities for mitochondria isolated from the different brain regions were similar, ranging from approximately 2.0–2.5 μmol mg−1 protein. Ten min cardiac arrest-induced global cerebral ischemia resulted in a significant reduction in the uptake capacity for all three brain regions compared to respective control mitochondria (p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA and the Duncan’s method for multiple pairwise comparisons). The uptake capacity following 10 min ischemia alone was reduced by 38%, 28%, and 55% for mitochondrial isolated from frontal cortex, striatum, and hippocampus, respectively. The uptake capacity for hippocampal mitochondria after ischemia alone was also significantly lower than that observed with cortical and striatal mitochondria (p < 0.05). Following 24 h reperfusion, the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake capacities for mitochondria from all three brain regions recovered and were not significantly different from those for non-ischemic animals but were significantly higher than those for the mitochondria following ischemia alone.

Fig. 2. Effects of ischemia and reperfusion on calcium uptake capacities of mitochondria isolated from cerebral cortex, striatum and hippocampus.

The mean calcium uptake capacities ± s.e. for mitochondria isolated from; A. cerebral cortex, B. striatum, and C. hippocampus were measured using tissue obtained from non-ischemic controls, animals that underwent 10 min cardiac arrest alone, and animals that underwent 10 min cardiac arrest followed by 24 h reperfusion. Measurements were performed at 37 °C in the presence of the respiratory substrates glutamate and malate and both ATP and Mg2+, as shown in Fig. 1B. and explained in Materials and Methods.

3.2. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake-induced respiratory inhibition

Fig. 1B indicates that the rate at which Ca2+ is accumulated by brain mitochondria declines as the maximal Ca2+ uptake capacity is approached. Since at the high Ca2+ concentrations used in these experiments the rate of Ca2+ uptake is limited by the rate of respiration-dependent proton efflux (Fiskum et al., 1979), we performed preliminary experiments to determine if the rate of O2 consumption also falls off under these conditions. We also compared the effects of Ca2+ on resting respiration (State 2) and maximal, ADP-stimulated oxidative phosphorylation (State 3 respiration) by mitochondria from a non-ischemic control brain to those of brain mitochondria following 10 min of cardiac arrest. As shown in Table 1, in the absence of added Ca2+, the State 2 rate of respiration was twice as high for the control mitochondria compared to the ischemic brain mitochondria. More importantly, the State 3 respiration by ischemic mitochondria was 30% lower than that of control mitochondria. Following exposure of control brain mitochondria to 0.3 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein, State 2 and State 3 respiratory rates were 30% and 25% greater, respectively, than the rates in the absence of Ca2+. In contrast, the State 2 rate observed with ischemic brain mitochondria exposed to this level of Ca2+ was 93% higher than in the absence of Ca2+. Moreover, the State 3 rate was 15% lower than in the absence of Ca2+. Respiration by both control and ischemic brain mitochondria was substantially altered by exposure to the much higher level of Ca2+ equal to 2.1 μmol mg−1 protein, which exceeds the uptake capacity of ischemic brain mitochondria and is close to the uptake capacity of control mitochondria (Fig. 2). At this level of Ca2+, the State 2 rate of respiration by control mitochondria was 93% higher than the rate in the absence of Ca2+. The State 2 rate for ischemic mitochondria was similar to that observed in the absence of Ca2+. However, at this level of Ca2+, there was an 83% inhibition of State 3 respiration, resulting in a State 3 rate equivalent to the State 2 rate. A similar effect of high Ca2+ was also observed with control brain mitochondria, with a 50% reduction in State 3 respiration which was also equivalent to State 3 respiration. In summary, the presence of 0.3 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein caused uncoupling to both control and ischemic mitochondria, as reflected by increases in State 2 respiration. This Ca2+ level also caused respiratory inhibition to ischemic but not control mitochondria, as reflected by the State 3 rates of O2 consumption. At the higher level of 2.1 μmol Ca2+ mg−1, severe respiratory inhibition and uncoupling was observed with frontal cortex mitochondria from both non-ischemic and ischemic brains. As observed with the Ca2+ uptake measurements, the presence of cyclosporin A had no effect on Ca2+-induced respiratory alterations (not shown).

Table 1.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake-induced respiratory inhibition.

| Calcium Added (μmol mg−1) | Respiration (nmol O2 min−1 mg protein−1)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State 2

|

State 3

|

|||

| Control | Ischemic | Control | Ischemic | |

| None | 28 | 14 | 110 | 78 |

| 0.3 | 36 | 27 | 138 | 67 |

| 2.0 | 54 | 16 | 55 | 13 |

Oxygen electrode measurements of respiration by isolated frontal cortex brain mitochondria were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Mitochondria were suspended at a concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1 in a KCL-based medium maintained at 37 °C containing the respiratory substrates glutamate plus malate, ATP, and Mg2+ at the same concentrations used in the Ca2+ uptake measurements. The initial rate of respiration (State 2) was measured and at 8 min, 0.4 mM ADP was added and the State 3 rate of respiration was measured. When present, CaCl2 was added at a level of either 0.3 or 2.1 μmol mg−1 protein at 1 min after the addition of mitochondria.

3.3. Cytochrome c release from normal, ischemic, and ischemic/reperfused brain mitochondria

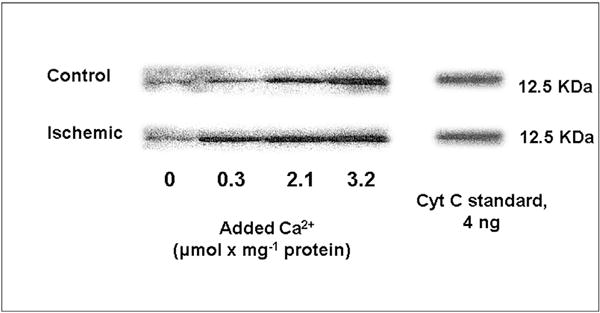

Excessive mitochondrial uptake of Ca2+ is one of several proposed mechanisms responsible for the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytoplasm where it can trigger caspase-dependent apoptosis (Smaili et al., 2000). Since cytochrome c is also a required component of the electron transport chain, its’ release into the cytosol could be responsible for impaired respiration and metabolic failure, leading to necrotic cell death. We measured the release of cytochrome c from brain mitochondria in vitro in the same experimental media containing Mg2+ and ATP used for Ca2+ uptake and O2 consumption measurements. At the end of 10 min incubation at 37° in the absence and presence of a single addition of Ca2+, the suspensions were rapidly centrifuged in a microcentrifuge and the supernatant and pellet fractions processed for immunoblot measurements of cytochrome c (see Methods). Fig. 3 provides an example of these immunoblots, demonstrating a Ca2+-dose dependent release of cytochrome c from the frontal cortex of non-ischemic and 10 min cardiac arrest animals.

Fig. 3. Western immunoblots of cytochrome c released from normal and ischemic canine cortex mitochondria in the absence and presence of calcium.

Brain mitochondria were isolated from non-ischemic animals and from animals after 10 min cardiac arrest alone. Mitochondria were suspended in respiratory medium in the absence or presence of 0.3, 2.1, and 3.2 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein. Following the 10 min incubation, a sample was removed and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 3 min and the supernatant removed for cytochrome c western immunoblots. The immunoblot bands were compared to those generated with purified cytochrome c.

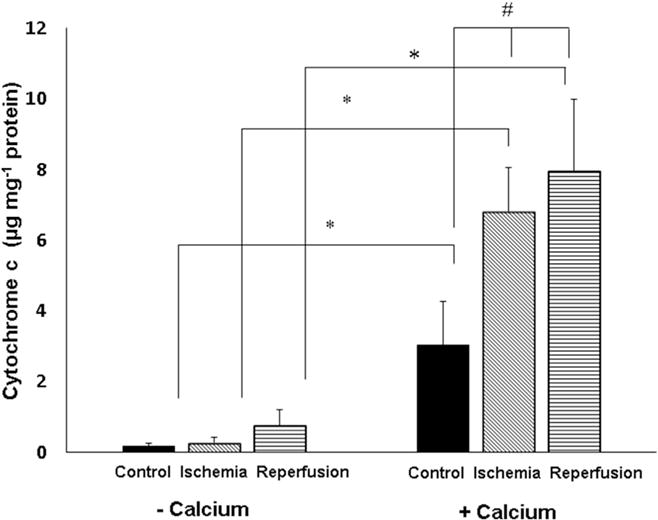

A summary of the densitometric quantification of cytochrome c immunoblots for incubations using frontal cortex mitochondria from n = 4 normal, ischemic and 24 h reperfused animals is provided in Fig. 4. There was no significant difference in the average spontaneous cytochrome c release that occurred in the absence of added Ca2+ for mitochondria from the three experimental groups. The presence of 2.1 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein resulted in a significant increase in cytochrome c release for all groups (p < 0.001) using one-way repeated measures ANOVA and the Student-Newman-Keuls Duncan’s method for multiple pairwise comparisons. At this level of Ca2+, there was also a significant increase in cytochrome c release for mitochondria from both ischemic and ischemia plus 24 h reperfusion groups compared to non-ischemic controls (p < 0.05). Measurements were also made of the cytochrome c present in the pellets following centrifugation of the mitochondrial incubations. When values for supernatants and pellets were compared, it was determined that the maximal cytochrome c released at 2.1 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein during these incubations was 48.5 ± 2.7% of total mitochondrial cytochrome c present in mitochondria from the reperfusion animal group. Qualitatively similar Ca2+-dependent cytochrome c release was also observed with canine brain mitochondria isolated from the hippocampus and striatum (not shown). The addition of cyclosporin A to the incubation media had no effect on cytochrome c release (not shown).

Fig. 4. Comparison of cytochrome c released from normal, ischemic, and ischemia/reperfused brains following incubation in the absence or presence of added calcium.

Brain mitochondria were isolated from non-ischemic animals and from animals after 10 min cardiac arrest alone (n = 4/group). Mitochondria were suspended in respiratory medium in the absence or presence of 2.1 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein. Release of cytochrome c was measured as described in Fig. 3. * Cytochrome c release was significantly greater in the presence of Ca2+ for all 3 animal groups in comparison to the absence of added Ca2+ (p < 0.001). # In the presence of Ca2+, cytochrome c release was significantly greater for mitochondria from ischemia or ischemia/reperfusion in comparison to release for non-ischemic, control brain mitochondria.

4. Discussion

Although isolated brain mitochondria have a very limited capacity for respiration-dependent Ca2+ uptake and retention in the absence of ATP and Mg2+ (Fig. 1A), in the presence of these agents and NAD-linked oxidizable substrates, mitochondria isolated from non-ischemic brains can accumulate over 2 μmol Ca2+ mg−1 protein (Fig. 2). Although at this juncture there is no comparable quantification of how much Ca2+ may be accumulated by mitochondria under conditions in which there is an excessive and (or) prolonged elevation of cytosolic Ca2+, several lines of evidence obtained in vitro indicate that Ca2+ uptake by neuronal mitochondria is important in buffering elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ generated through the binding of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate to its receptors; however, excessive uptake can also result in mitochondrial injury and cell death in the presence of excitotoxic levels of glutamate or glutamate agonists (Ankarcrona et al., 1995; Reynolds and Hastings, 1995; Dugan et al., 1995; White and Reynolds, 1996; Budd and Nicholls, 1996; Castilho et al., 1999; Laird et al., 2013). Following only 5–10 min of cerebral ischemia, neuronal cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations can exceed 30 μM (Silver and Erecinska, 1990). Therefore, neuronal mitochondria are exposed to supranormal Ca2+ concentrations during post ischemic reperfusion as well as during other related situations when there is pathologic excitotoxic stimulation, e.g., seizure activity. Previous results obtained with isolated rat brain mitochondria indicate that mitochondrial Ca2+ influx can be impaired following prolonged decapitation ischemia (Sciamanna et al., 1992). Our new observation that the capacity for Ca2+ accumulation by brain mitochondria in the presence of physiologically realistic concentrations of Mg2+, ATP, etc. is substantially reduced (Fig. 2) and that sensitivity to Ca2+-induced respiratory inhibition is exacerbated following 10 min of normothermic cardiac arrest supports the hypothesis that ischemic mitochondrial alterations promote further reperfusion-dependent modifications that contribute to the pathogenesis of neuronal cell death and neurological impairment. Studies are in progress to determine the additional effects of ischemia-relevant factors, e.g., acidic pH, on the ability of mitochondria from normal and injured brains to accumulate Ca2+.

In addition to the observations of the effects of cerebral ischemia and reperfusion on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake capacity and respiration, this study is the first to document the effects of in vivo global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion on the sensitivity of brain mitochondria to Ca2+-induced release of the apoptogenic factor cytochrome c (Figs. 3 and 4). However, a qualitatively similar increase in sensitivity to Ca2+ was observed in vitro following exposure of isolated brain mitochondria to hypoxia/reoxygenation (Schild and Reiser, 2005). The potential relevance of this phenomenon is underscored by the demonstrations of cytochrome c release into the cytosol of brain cells in vivo following both focal and global cerebral ischemia (Fujimura et al., 1998; Perez-Pinzon et al., 1999).

It is particularly noteworthy that unlike the normal Ca2+ uptake and respiratory characteristics exhibited by brain mitochondria isolated following 24 h reperfusion (Fig. 2), mitochondria from 24 h reperfused animals demonstrated a significantly enhanced sensitivity to cytochrome c release by exposure to high levels of ambient Ca2+ in vitro. These observations suggest that the mechanism of enhancement of Ca2+-induced cytochrome c release caused by ischemia and reperfusion is at least somewhat different than the mechanism of altered handling of Ca2+ observed following ischemia alone. The elevated Ca2+-induced cytochrome c release observed with brain mitochondria at 24 h could, for example, be connected with increased translocation of the pro-apoptotic Bax peptide from the cytosol to mitochondria, which has been observed in at least one other global cerebral ischemia study (Han et al., 2011). We previously reported an increase in Bax immunoreactivity in canine hippocampal homogenates at 24 h of reperfusion (Krajewska et al., 2004); however, we did not measure Bax levels in the cortical mitochondria used in the cytochrome c release measurements. Bax can oligomerize and form megapores in the outer membrane, resulting in Ca2+-independent release of cytochrome c (Polster et al., 2001). In addition, Bax may interact with specific mitochondrial proteins, e.g., the voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC), thereby promoting Ca2+-dependent PTP opening (Morin et al., 2009; Karch et al., 2013; Whelan et al., 2012). While the potential reperfusion-dependent elevation of mitochondrial Bax could explain the relatively high degree to which cytochrome c is released by Ca2+ from brain mitochondria from 24 h reperfused animals, this hypothesis is apparently inconsistent with the fact that the Ca2+ uptake capacity of these mitochondria are greater than the mitochondria isolated following ischemia alone and are not different than the Ca2+ capacity of non-ischemic brain mitochondria (Fig. 2). Another explanation is that the fraction of cytochrome c that is Ca2+-releasable may increase following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Most of cytochrome c is located deep within the inner membrane cristae and therefore not near the outer membrane. Evidence indicates that cristae restructuring occurs early during mitochondrial apoptosis, thereby increasing the level of cytochrome c that can be released either indirectly by PTP opening or directly by Bax or Bak outer membrane megapore formation (Karch et al., 2013; Scorrano et al., 2002). The Optic Atrophy 1 (OPA1) mitochondrial inner membrane protein is necessary for maintaining normal cristae structure and cytochrome c localization (Frezza et al., 2006). The fact that OPA1 is proteolytically degraded in a rat model of cerebral ischemia reperfusion could also help explain why Ca2+-induced cytochrome c release is high in mitochondria 24 h after cardiac arrest and resuscitation (Baburamani et al., 2015).

Increasing evidence supports the involvement of both mitochondrial sequestration and cytochrome c release in the pathogenesis of both acute ischemic and traumatic neurologic injury and chronic neurodegeneration (Thornton and Hagberg, 2015; Cali et al., 2012; Perez-Pinzon et al., 2012; Polster and Fiskum, 2004). Further elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for Ca2+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cytochrome c release will be important in developing interventions directed at the early events responsible for both necrotic and apoptotic neuronal death.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS34152 and R01NS091099. We wish to thank Mr. Stephen Russell for his expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- EGTA

ethylene glycol bis-(p-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′N′–tetra acetic acid

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethane sulfonic acid

References

- Andreyev A, Fahy B, Fiskum G. Cytochrome c release from brain mitochondria is independent of the mitochondrial permeability transition. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:373–376. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev A, Fiskum G. Calcium induced release of mitochondrial cytochrome c by different mechanisms selective for brain versus liver. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:825–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton SA, Nicotera P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: a succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron. 1995;15:961–973. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baburamani AA, Hurling C, Stolp H, Sobotka K, Gressens P, Hagberg H, Thornton C. Mitochondrial optic atrophy (OPA) 1 processing is altered in response to neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:22509–22526. doi: 10.3390/ijms160922509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan IS, Fiskum G, Hazelton J, Cotto-Cumba C, Rosenthal RE. Oximetry-guided reoxygenation improves neurological outcome after experimental cardiac arrest. Stroke. 2006;37:3008–3013. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000248455.73785.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossy-Wetzel E, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. Mitochondrial cytochrome c release in apoptosis occurs upstream of DEVD-specific caspase activation and independently of mitochondrial transmembrane depolarization. EMBO J. 1998;17:37–49. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham CA, Qian T, Streetz K, Trautwein C, Brenner DA, Lemasters JJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis and cytochrome c release. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6353–6364. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton BR, Reutens DC, Sobey CG. Apoptotic mechanisms after cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:e331–e339. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Nicholls DG. Mitochondria, calcium regulation, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2282–2291. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Yang J, Jones DP. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis: the role of cytochrome c. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cali T, Ottolini D, Brini M. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) and neurodegeneration. Cell Calcium. 2012;52:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilho RF, Ward MW, Nicholls DG. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1394–1401. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell JB, Crofts AR. Calcium ion accumulation and volume changes of isolated liver mitochondria. calcium ion-induced swelling. Biochem J. 1965;95:378–386. doi: 10.1042/bj0950378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Graham SH, Chan PH, Lan J, Zhou RL, Simon RP. bcl-2 is expressed in neurons that survive focal ischemia in the rat. Neuroreport. 1995;6:394–398. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199501000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese JD, Voglino AL, Hackenbrock CR. Persistence of cytochrome c binding to membranes at physiological mitochondrial intermembrane space ionic strength. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1228:216–228. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest TG, Schuh RA, Waddell J, McKenna MC, Fiskum G. Sex-dependent mitochondrial respiratory impairment and oxidative stress in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Neurochem. 2016;137:714–729. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, Joh HD, Bernard O, Hattori K, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Alkayed NJ. Social stress exacerbates stroke outcome by suppressing Bcl-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11824–11828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201215298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Sensi SL, Canzoniero LM, Handran SD, Rothman SM, Lin TS, Goldberg MP, Choi DW. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species in cortical neurons following exposure to N-methyl-D-aspartate. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6377–6388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06377.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskum G, Cockrell RS. Uncoupler-stimulated Ca2+ efflux by Ehrlich ascites tumor mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;240:723–733. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskum G, Murphy AN, Beal MF. Mitochondria in neurodegeneration: acute ischemia and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:351–369. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskum G, Reynafarje B, Lehninger AL. The electric charge stoichiometry of respiration-dependent Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:6288–6295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JL. Redox regulation of the intrinsic pathway in neuronal apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1437–1448. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza C, Cipolat S, Martins de BO, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Rudka T, Bartoli D, Polishuck RS, Danial NN, De SB, Scorrano L. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006;126:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Murakami K, Kawase M, Chan PH. Cytosolic redistribution of cytochrome c after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1239–1247. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Heart mitochondria: gates of life and death. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:334–343. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg H, Mallard C, Rousset CI, Xiaoyang W. Apoptotic mechanisms in the immature brain: involvement of mitochondria. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:1141–1146. doi: 10.1177/0883073809338212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Wang Q, Cui G, Shen X, Zhu Z. Post-treatment of Bax-inhibiting peptide reduces neuronal death and behavioral deficits following global cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrow SP, Piantadosi CA. Release of cytochrome c from liver mitochondria during permeability transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:669–671. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch J, Kwong JQ, Burr AR, Sargent MA, Elrod JW, Peixoto PM, Martinez-Caballero S, Osinska H, Cheng EH, Robbins J, Kinnally KW, Molkentin JD. Bax and Bak function as the outer membrane component of the mitochondrial permeability pore in regulating necrotic cell death in mice. Elife. 2013;2:e00772. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: a primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. see comment Science. 1997;275(5303):1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski AJ, Fiskum G. Redox mechanisms of cytoprotection by bcl-2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:508–514. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewska M, Rosenthal RE, Mikolajczyk J, Stennicke HR, Wiesenthal T, Mai J, Naito M, Salvesen GS, Reed JC, Fiskum G, Krajewski S. Early processing of Bid and caspase-6, -8, -10, -14 in the canine brain during cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Exp Neurol. 2004;189:261–279. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski S, Mai JK, Krajewska M, Sikorska M, Mossakowski MJ, Reed JC. Upregulation of bax protein levels in neurons following cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6364–6376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06364.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Zamzami N, Susin SA. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird MD, Clerc P, Polster BM, Fiskum G. Augmentation of normal and glutamate-impaired neuronal respiratory capacity by exogenous alternative biofuels. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0275-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Rosenthal RE, Haywood Y, Miljkovic-Lolic M, Vanderhoek JY, Fiskum G. Normoxic ventilation after cardiac arrest reduces oxidation of brain lipids and improves neurological outcome. Stroke. 1998;29:1679–1686. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.8.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Dubois-Dauphin M, Staple JK, Rodriguez I, Frankowski H, Missotten M, Albertini P, Talabot D, Catsicas S, Pietra C. Over-expression of BCL-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia. Neuron. 1994;13:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlib MA, O’Brien PJ. Properties of rat liver mitochondria with inter-membrane cytochrome c. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976;173:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin D, Assaly R, Paradis S, Berdeaux A. Inhibition of mitochondrial membrane permeability as a putative pharmacological target for cardioprotection. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:4382–4398. doi: 10.2174/092986709789712871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AN, Bredesen DE, Cortopassi G, Wang E, Fiskum G. Bcl-2 potentiates the maximal calcium uptake capacity of neural cell mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996a;93:9893–9898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AN, Kelleher JK, Fiskum G. Submicromolar Ca2+ regulates phosphorylating respiration by normal rat liver and AS-30D hepatoma mitochondria by different mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10527–10534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AN, Myers KM, Fiskum G. Bcl-2 and N-acetylcysteine inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory impairment following exposure of neural cells to chemical hypoxia/aglycemia. In: Krieglstein J, editor. Pharmacology of Cerebral Ischemia Wissenschaftliche Verlugsgesellschaft, Stuttgart, Germany. 1996b. pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Fiskum G, Liu Y, Simmens SJ, Bredesen DE, Murphy AN. Bcl-2 protects neural cells from cyanide/aglycemia-induced lipid oxidation, mitochondrial injury, and loss of viability. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2432–2440. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niquet J, Seo DW, Wasterlain CG. Mitochondrial pathways of neuronal necrosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1347–1351. doi: 10.1042/BST0341347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow YP, Green DR, Hao Z, Mak TW. Cytochrome c: functions beyond respiration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:532–542. doi: 10.1038/nrm2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino JG, Chen ST, Tafani M, Snyder JW, Farber JL. The over-expression of Bax produces cell death upon induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7770–7775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Stetler RA, Fiskum G. Novel mitochondrial targets for neuroprotection. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1362–1376. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Xu GP, Born J, Lorenzo J, Busto R, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Cytochrome c is released from mitochondria into the cytosol after cerebral anoxia or ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:39–43. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer DR, Gudz TI, Novgorodov SA, Erdahl WL. The peptide mastoparan is a potent facilitator of the mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4923–4932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polster BM, Fiskum G. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neural cell apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1281–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polster BM, Kinnally KW, Fiskum G. BH3 death domain peptide induces cell type-selective mitochondrial outer membrane permeability. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37887–37894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds IJ, Hastings TG. Glutamate induces the production of reactive oxygen species in cultured forebrain neurons following NMDA receptor activation. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3318–3327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03318.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal RE, Hamud F, Fiskum G, Varghese PJ, Sharpe S. Cerebral ischemia and reperfusion: prevention of brain mitochondrial injury by lidoflazine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1987;7:752–758. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1987.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg H, Marbach M. Adenine nucleotides regulate Ca2+ transport in brain mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1989;247:483–486. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda CB, Llorente-Folch I, Traba J, Amigo I, Gonzalez-Sanchez P, Contreras L, Juaristi I, Martinez-Valero P, Pardo B, Del AA, Satrustegui J. Glutamate excitotoxicity and Ca2+-regulation of respiration: role of the Ca2+ activated mitochondrial transporters (CaMCs) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:1158–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlett JL, Murphy MP. Release of apoptogenic proteins from the mitochondrial intermembrane space during the mitochondrial permeability transition. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:282–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild L, Reiser G. Oxidative stress is involved in the permeabilization of the inner membrane of brain mitochondria exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation and low micromolar Ca2+ FEBS J. 2005;272:3593–3601. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciamanna MA, Zinkel J, Fabi AY, Lee CP. Ischemic injury to rat forebrain mitochondria and cellular calcium homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1134:223–232. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90180-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorrano L, Ashiya M, Buttle K, Weiler S, Oakes SA, Mannella CA, Korsmeyer SJ. A distinct pathway remodels mitochondrial cristae and mobilizes cytochrome c during apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver IA, Erecinska M. Intracellular and extracellular changes of [Ca2+] in hypoxia and ischemia in rat brain in vivo. J Gen Physiol. 1990;95:837–866. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.5.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarkowska L, Klingenberg M. On the role of ubiquinone in mitochondria. Biochem Z. 1963;338:674–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaili SS, Hsu YT, Youle RJ, Russell JT. Mitochondria in Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2000;32:35–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1005508311495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton C, Hagberg H. Role of mitochondria in apoptotic and necroptotic cell death in the developing brain. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;451:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjioe S, Bianchi CP, Haugaard N. The function of ATP in Ca2+ uptake by rat brain mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;216:270–273. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(70)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toman J, Fiskum G. Influence of aging on membrane permeability transition in brain mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2011;43:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s10863-011-9337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaagenes P, Cantadore R, Safar P, Moossy J, Rao G, Diven W, Alexander H, Stezoski W. Amelioration of brain damage by lidoflazine after prolonged ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in dogs. Crit Care Med. 1984;12:846–855. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Williamson EK, Schumacker PT, Thompson CB. Bcl-xL regulates the membrane potential and volume homeostasis of mitochondria. Cell. 1997;91:627–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Thayer SA. Sequestration of glutamate-induced Ca2+ loads by mitochondria in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1611–1621. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Michaelis EK. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan RS, Konstantinidis K, Wei AC, Chen Y, Reyna DE, Jha S, Yang Y, Calvert JW, Lindsten T, Thompson CB, Crow MT, Gavathiotis E, Dorn GW, O’Rourke B, Kitsis RN. Bax regulates primary necrosis through mitochondrial dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6566–6571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201608109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondria and Na+/Ca2+ exchange buffer glutamate-induced calcium loads in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1318–1328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01318.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial depolarization in glutamate-stimulated neurons: an early signal specific to excitotoxin exposure. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5688–5697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05688.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP, Wang X. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. see comment Science. 1997;275(5303):1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JC, Cortopassi GA. Induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition causes release of the apoptogenic factor cytochrome c. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:624–631. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Li X, Li F, Li J, Chang W, Yuan J, Chen J. Cyclosporin A protects against Lead neurotoxicity through inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in nerve cells. Neurotoxicology. 2016;57:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J, Dinsdale D, Cohen GM. Apoptosis, in human monocytic THP.1 cells, results in the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria prior to their ultracondensation, formation of outer membrane discontinuities and reduction in inner membrane potential. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:953–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]