Abstract

Objective:

A substantial evidence base in the peer-reviewed literature exists investigating mental illness in the military, but relatively less is documented about mental illness in veterans. This study uses provincial, administrative data to study the use of mental health services by Canadian veterans in Ontario.

Method:

This was a retrospective cohort study of Canadian Armed Forces and Royal Canadian Mounted Police veterans who were released between 1990 and 2013 and resided in Ontario. Mental health–related primary care physician, psychiatrist, emergency department (ED) visits, and psychiatric hospitalisations were counted. Repeated measures were presented in 5-year intervals, stratified by age at release.

Results:

The cohort included 23,818 veterans. In the first 5 years following entry into the health care system, 28.9% of veterans had ≥1 mental health–related primary care physician visit, 5.8% visited a psychiatrist at least once, and 2.4% received acute mental health services at an ED. The use of mental health services was consistent over time. Almost 8% of veterans aged 30 to 39 years saw a psychiatrist in the first 5 years after release, compared to 3.5% of veterans aged ≥50 years at release. The youngest veterans at release (<30 years) were the most frequent users of ED services for a mental health–related reason (5.1% had at least 1 ED visit).

Conclusion:

Understanding how veterans use the health care system for mental health problems is an important step to ensuring needs are met during the transition to civilian life.

Keywords: veteran, veteran health, military personnel, health services, mental disorders

Abstract

Objectif:

Il y a une recherche substantielle fondée sur des données probantessur la maladie mentale chez les militaires, mais elle est relativement peu documentée dans la littérature révisée par les pairs quand il s’agit de maladie mentale chez les anciens combattants. Cette étude utilise des données provinciales, administratives pour étudier l’utilisation des services de santé mentale par les anciens combattants de l’Ontario.

Méthodologie:

C’était une étude de cohorte rétrospective des anciens combattants des Forces armées canadiennes (FAC) et de la Gendarmerie royale du Canada (GRC) qui ont été libérés entre 1990 et 2013 et résidaient en Ontario. Les visites liées à la santé mentale à un médecin des soins de première ligne, à un psychiatre ou à un service d’urgence (SU) ainsi que les hospitalisations psychiatriques ont été comptées. Les mesures répétées ont été présentées à cinq ans d’intervalle, stratifiées selon l’âge à la libération.

Résultats:

La cohorte comprenait 23818 anciens combattants. Dans les cinq premières années suivant l’entrée dans le système de santé, 28,9% des anciens combattants avaient ≥ 1 visite liée à la santé mentale à un médecin des soins de première ligne, 5,8% avaient vu un psychiatre au moins une fois, et 2,4% avaient reçu des soins actifs de santé mentale à un service d’urgence. L’utilisation des services de santé mentale était constante avec le temps. Presque 8% des anciens combattants de 30 à 39 ans ont vu un psychiatre dans les 5 premières années après la libération, comparé à 3,5% des anciens combattants de ≥ 50 ans à la libération. Les anciens combattants les plus jeunes à la libération (< 30 ans) étaient les utilisateurs les plus fréquents des services d’urgence pour une raison liée à la santé mentale (5,1% avaient au moins une visite au SU).

Conclusion:

Comprendre comment les anciens combattants utilisent le système de santé pour des problèmes de santé mentale est une étape importante pour faire en sorte de répondre à leurs besoins durant la transition à la vie civile.

The mental health of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel is a national priority. In a cross-sectional survey by the Department of National Defense (DND) Canadian Forces Health Services Group, 16.5% of CAF regular force personnel reported 1 of 6 past-year mental disorders.1 Zamorski et al.1 documented increasing 1-year prevalence rates for major depressive episode, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalised anxiety disorder, at 8.0%, 5.3%, and 4.7%, respectively, between 2002 and 2013. Sareen et al.2 reported an increase in mental health help-seeking behaviour in military personnel over the past decade, as well as a significantly larger proportion of military personnel having contact with a psychiatrist, nurse, social worker, psychologist, or family physician for mental health reasons compared to the civilian population. Boulos and Zamorski3 reported improvements in the time from deployment to use of mental health services over time and concluded this was the result of CAF mental health system changes. Fikretoglu et al.4 stated a significantly larger proportion of military personnel who reported needing mental health services had their needs met compared to the civilian population.

The mental health of CAF veterans is also of national importance. In the most recent iteration of a national survey of Canadian veterans, 23% reported having been diagnosed with 1 or more mental disorders, 5.8% reported suicidal ideation, and 1.1% reported a suicide attempt in the previous year.5 These studies have documented comorbidity between physical and mental health disorders, as well as identified correlates of suicidal ideation.6 There has also been significant documentation of mental health diagnoses and clinical management at specialised Operational Stress Injury clinics serving treatment-seeking veterans who qualify for care funded by Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC).7–9 For example, Richardson et al.10 concluded that primary and specialist health services use in peacekeeping veterans was associated with PTSD and depression symptom severity. Very few studies describing access to or use of services exist.

Understanding mental health service use for veterans is particularly challenging, given that services are provided provincially within the public health care system and separately funded by VAC through specialised services such as the Operational Stress Injury (OSI) clinics.11 Available, relevant information is derived primarily from national, cross-sectional surveys. These self-reported data may underestimate true utilisation compared to health care administrative records, such as physician billing or inpatient admission records.12 Additional mental health services use data are limited to describing those veterans who seek mental health care in specialised programs and who qualify for coverage of federal services.7 While these data sources provide insights into veteran mental health, most mental health services are provided through provincial programs. Using population-based data at the provincial level would provide an additional perspective to understanding the mental health burden and an accurate description of provincial mental health services use.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a retrospective, cohort study using provincial, administrative health care data to study the use of mental health services by CAF and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) veterans living in Ontario. Ontario is home to 8 of the 38 Canadian federal military bases, including Canadian Forces Base Kingston, the largest Army base in the country; the Royal Military College of Canada; the DND Headquarters; and the national headquarters for the RCMP. VAC estimated that 31% of veterans transition from the military to civilian residence in Ontario each year.13 Most of our cohort are likely to be CAF veterans rather than RCMP.14

Identifying Veteran Status

In Canada, the health care of CAF personnel and the RCMP was federally regulated during the study timeframe. Full-time, non-Reserves CAF personnel are provided specialised health services within a federal health care system. CAF Regular Forces veterans transition to the public, provincial/territorial health care system of their province/territory of residence when they exit the military. Until April 1, 2013, RCMP officers received health care within the provincial system but were considered out of province, and their health services delivery was billed to the federal government. In Ontario, the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC) tracks registration for provincial health care coverage for previous CAF and RCMP members with a single administrative marker. For this study, veterans were defined as Canadian CAF and RCMP service leavers who provided evidence to the Ontario MOHLTC care of their career history at some point in time following release. The MOHLTC provided the authors with the anonymized list of people with an administrative CAF and RCMP service code linked to their health card number, as well as career start and end dates. Details on cohort creation, demographics, and medical health service use are provided elsewhere.14–16

We included individuals in this study if they registered for Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) coverage with the MOHLTC between January 1, 1990, and March 31, 2013. We excluded individuals with OHIP coverage while still engaged in CAF or RCMP service. Individuals were followed until death, OHIP coverage ended (e.g., moved out of province), or the end of the study period (March 31, 2014). The date of OHIP registration is a close approximation of the veterans’ release date from the CAF or RCMP.14 However, we do not have information on how often veterans do not register for provincial health insurance. We have discussed the representativeness of the cohort elsewhere and will summarise here.14 The number of veterans entering our cohort per year was similar to the expected number reported releasing to Ontario by VAC. We found a similar age and sex distribution in our cohort as reported by VAC, as well as a similar distribution of length of service. Our cohort has fewer younger veterans and a larger number of older veterans than reported by VAC; however, this is likely explained by our inclusion of RCMP veterans.14

Data Sources

The study combined 6 administrative data sets held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). These data sets were linked at the individual level using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES. The Registered Persons Database provided sociodemographic data on age, sex, region, and rurality of residence in Ontario, as well as aggregate community-level median income. The OHIP database provided information on physician services, including physician visits, as well as diagnostic information. Physician specialty, designated as family physician or psychiatrist, was measured using the ICES Physician Database (IPDB). The National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) provided diagnostic and service information on emergency department (ED) visits. The Canadian Institute for Health Information–Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD) and the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS) provided information on psychiatric admissions. The OMHRS is a specialised psychiatric data set begun in 2005 to house inpatient psychiatric admissions occurring within psychiatric institutions and psychiatric wards of provincial hospitals.

Publicly funded mental health services were the primary outcomes of the study. Family physician and psychiatrist visits were identified using the OHIP database, linked to physician specialty data in the IPDB. OHIP databases include diagnosis data using a modified version of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) classification system. A list of the mental health diagnoses is provided in Supplemental Table S1. Family physician visits were counted if the diagnosis was a mental disorder. All OHIP records billed by a psychiatrist were counted, regardless of diagnosis. Psychiatric ED visits were identified from all ED visits using the NACRS database. A combination of CIHI-DAD and OMHRS data was used to identify psychiatric hospitalisations and cumulative psychiatric inpatient stay. NACRS and CIHI-DAD include diagnosis data following the ICD-9 and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) classification system. The list of diagnosis codes used to identify mental health encounters is provided in Supplemental Table S1. All OMHRS hospitalisations were included. An ED visit or CIHI-DAD hospitalisation was counted if the primary diagnosis was a mental disorder. Cumulative psychiatric inpatient stay was defined as the total number of days spent in hospital for a mental health disorder during the study timeframe, regardless of the number of readmissions or location of stay. Health services were measured both as dichotomous outcomes (yes/no) and as counts (number of visits).

We described mental health service use with frequencies, proportions, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for categorical variables with 1-sample proportion CIs calculated using the Normal approximation to the binomial distribution. Continuous and count data are described using their mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). Results were stratified by 5-year time intervals following release (0-5 years, 5-10 years, 10-15 years, and 15-20 years) and age at release, to explore temporal and age-related patterns in mental health service use. Chi-square tests for independence were conducted to compare rates of mental health services use across age at release categories in the first 5 years following release; P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Comparisons to the general population were not made due to methodological concerns about validity. There is evidence that the healthy worker effect or healthy warrior effect biases comparisons between veterans and the general population.17

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was granted ethical clearance by the Queen’s University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board. The project was also approved by the ICES and the MOHLTC.

Results

The final cohort included 23,818 CAF and RCMP veterans (Suppl. Figure S1). Table 1 describes the veteran cohort in the first five years after leaving the CAF/RCMP. The average age at the start of the military or RCMP career was 24 years, and 38.4% were younger than 40 years when they finished their career; 27.7% of the cohort served for 10 or fewer years. Most (85.7%) of the cohort is male. Almost half the cohort (48.0%) left the CAF or RCMP between 1990 and 2000; 9.1% left the CAF or RCMP between 2010 and 2013. The average amount of follow-up time was 9.33 years (SD, 6.13).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Canadian Veterans in Ontario at Entry into the Provincial Health Care System (n = 23,818).

| Demographic Characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Age at transition from the CAF/RCMP | |

| <30 | 15.7 |

| 30-39 | 22.8 |

| 40-49 | 36.0 |

| 50+ | 25.6 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 14.3 |

| Median community income | |

| Lowest | 10.4 |

| 2 | 17.1 |

| 3 | 20.8 |

| 4 | 25.5 |

| Highest | 21.8 |

| Missing | 4.5 |

| Local Health Integration Network | |

| Erie St. Clair | 1.5 |

| South West | 3.9 |

| Waterloo Wellington | 1.5 |

| Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant | 2.8 |

| Central West | 0.7 |

| Mississauga Halton | 1.2 |

| Toronto Central | 0.8 |

| Central | 2.0 |

| Central East | 2.4 |

| South East | 19.9 |

| Champlain | 47.0 |

| North Simcoe Muskoka | 7.9 |

| North East | 3.9 |

| North West | 0.5 |

| Missing | 4.1 |

| Rurality | |

| Urban | 82.0 |

| Rural | 9.4 |

| Rural—remote | 6.1 |

| Rural—very remote | 1.0 |

| Rural—unknown | 1.4 |

| Year of transition from the CAF/RCMP | |

| 1990-1995 | 23.2 |

| 1996-2000 | 24.8 |

| 2001-2005 | 20.0 |

| 2006-2010 | 22.9 |

| 2011-2013 | 9.1 |

| Length of service (years) | |

| 0-4 | 20.0 |

| 5-9 | 12.8 |

| 10-19 | 15.3 |

| 20-29 | 33.1 |

| 30+ | 18.8 |

CAF, Canadian Armed Forces; RCMP, Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

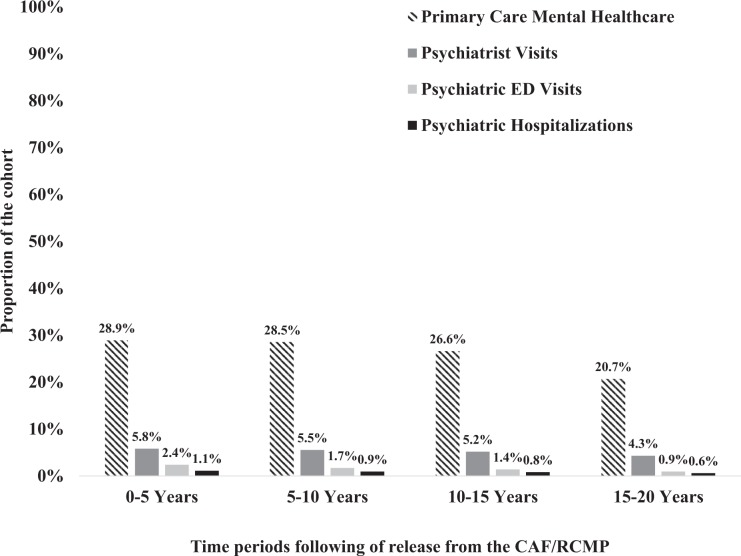

Figure 1 describes the proportion of veterans who accessed public mental health services. More than one-quarter of veterans (28.9%; 95% CI, 28.3-29.5) saw a family physician in the first 5 years following transition from the CAF or RCMP. Almost 6% of veterans had at least 1 visit with a psychiatrist in the first 5 years (5.8; 95% CI, 5.5-6.1). A very small proportion of veterans presented to the ED with a mental health–related complaint or required psychiatric hospitalisation. Mental health service use was relatively stable over time.

Figure 1.

The proportion of veterans in Ontario who received mental health treatment in primary care, with a psychiatrist, in the emergency department (ED) or during a psychiatric hospitalization at least once, stratified by the time period following release from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF)/Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

Table 2 reports average utilisation of each mental health service in those veterans who used the service at least once. Veterans consistently visited a primary care physician for mental health services on average 4 times each 5-year period. Veterans visited a psychiatrist an average of 12 times each 5-year period, with the exception of the 15 to 20 years post-transition, where the average number of visits was 9. The median number of visits per veteran, among those veterans who saw a psychiatrist at least once, was much lower in each time period, at 4 psychiatrist visits per veteran. The mean and median number of psychiatric ED visits was approximately 1.5 visits per veteran, per 5-year time period.

Table 2.

Average Mental Health Care Utilization in Veterans with at Least 1 Visit or Admission, Stratified by 5-Year Intervals following Transition from the CAF/RCMP.

| Time Intervals following Entry into the Provincial Health Care System | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Visits | 0-5 Years | 5-10 Years | 10-15 Years | 15-20 Years |

| Primary care | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (11.0) | 4.5 (9.9) | 4.1 (10.2) | 3.6 (8.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) |

| Psychiatrist | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.4 (26.3) | 12.8 (27.2) | 12.1 (34.0) | 9.4 (16.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (1-12) | 4 (1-12) | 3 (1-10) | 4 (1-10) |

| Psychiatric ED | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.8 (3.3) | 1.7 (2.1) | 1.5 (2.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1 -1) |

CAF, Canadian Armed Forces; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; RCMP, Royal Canadian Mounted Police; SD, standard deviation.

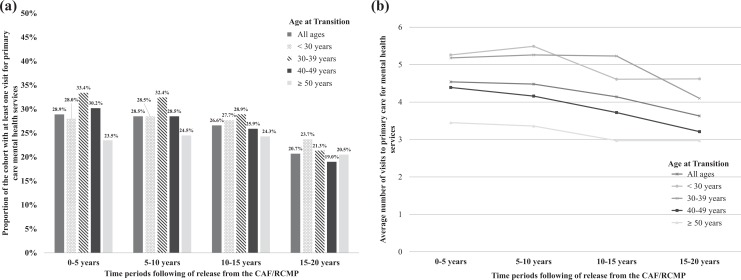

Figures 2 to 4 report the age-stratified use of primary care physician mental health care, psychiatry, and psychiatric ED presentations over time. Supplemental Table S2 reports the age-stratified 95% CIs, and Supplementary Table S3 reports the age-stratified averages, SDs, medians, and IQRs. Figure 2a,b describes the use and intensity of use of primary care physician mental health services. In the first 5 years following transition from the CAF or RCMP, a significantly larger proportion of veterans aged 30 to 39 years at the time of release engaged in primary care physician mental health care services, compared to the youngest and oldest veterans (P < 0.001). This trend persisted in the 5 to 10 years following transition.

Figure 2.

(a) The proportion of veterans in Ontario with at least 1 visit to primary care for mental health services, stratified by age of the veteran at the time of release from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF)/Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). (b) The average number of primary care mental health visits per veteran in Ontario, in those veterans who had at least 1 visit, stratified by age at the time of release from the CAF/RCMP. *The average was calculated for veterans using this service at least once over the time interval.

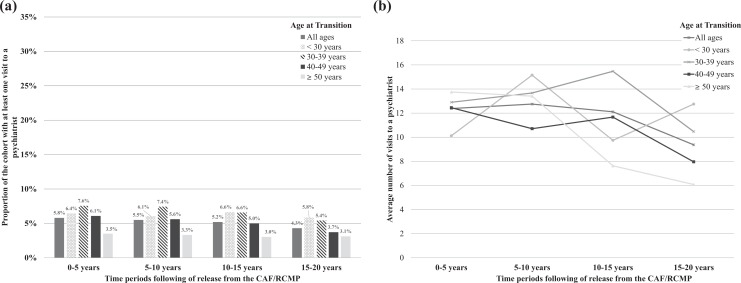

Figure 3.

(a) The proportion of veterans in Ontario visiting a psychiatrist, stratified by age at the time of release from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF)/Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). (b) The average number of psychiatrist visits by veterans in Ontario, in those who saw a psychiatrist, stratified by age of the veteran at the time of release from the CAF/RCMP. *The average was calculated for veterans using this service at least once over the time interval.

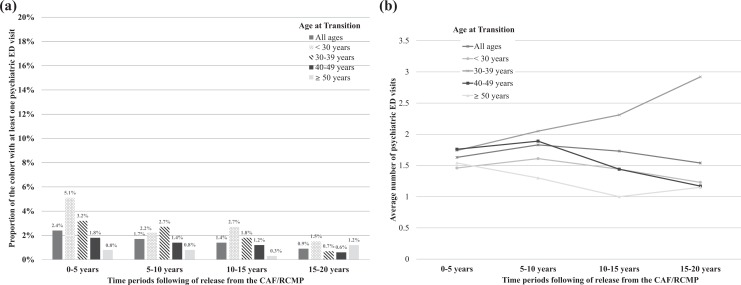

Figure 4.

(a) The proportion of veterans in Ontario with at least 1 psychiatric emergency department (ED) visit, stratified by age at the time of release from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF)/Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). (b) The average number of psychiatric ED visits by veterans in Ontario, in those veterans who had at least 1 visit, stratified by age of the veteran at the time of release from the CAF/RCMP.

Figure 3a,b describes the use and intensity of mental health care services provided by a psychiatrist, stratified by veteran age at transition. A significantly smaller proportion of veterans aged 50 years and older received mental health care from a psychiatrist in the provincial health system, relative to younger veterans (P < 0.001). These differences persisted until 15 to 20 years following transition from the CAF/RCMP. The average number of visits to a psychiatrist ranged from 10.1 (age <30) to 13.8 (age ≥50) in the first 5 years, and there were no clear patterns in the intensity of psychiatry care over time.

Figure 4a,b describes the use and intensity of acute mental health care services in the ED, stratified by veteran age at transition. In the first 5 years following transition from the CAF/RCMP, a small but significantly larger proportion of veterans younger than 30 years at the time of transition had at least 1 psychiatric ED visit, relative to older veterans (P < 0.001). In the 5 to 10 years following transition, the proportion of veterans with at least 1 psychiatric ED visit in the youngest age group dropped, and the rates were more similar across age categories; however, a significantly smaller proportion of veterans older than 50 years at the time of transition had a psychiatric ED visit across all time periods. In the first 5 years following release, the 4 most commonly reported psychiatric ED diagnoses were related to anxiety, depression, alcohol or drugs, or PTSD/panic disorders/acute stress reactions. These were common across age categories, with the exception of the 50 and older veteran age group; this group did not have any visits to the ED related to PTSD/panic disorders/acute stress reactions. The average number of psychiatric ED visits in the first 5 years was similar across age categories at release.

Psychiatric hospitalisations funded by the provincial government were rare following transition (Suppl. Tables S2 and S3). In the first 5 years, the mean number of cumulative psychiatric hospital days among veterans with a hospitalisation ranged from 18.5 in the group younger than 30 years at transition to 35.4 in the 50 years and older age group. The trend of longer psychiatric stays for older veterans was constant over time.

Discussion

This is the first longitudinal description of mental health services use by Canadian veterans in any provincial health care system. Over one-quarter of veterans in Ontario sought mental health services in the public, primary care sector. A much smaller proportion received provincially funded psychiatrist care, required acute mental health care in the ED, or had a psychiatric admission. The intensity of mental health service use did not diminish significantly over time in veterans requiring mental health services. This is contrary to the notion that a peak service use may exist shortly following release. The persistent nature of this need has important implications for service and delivery and may be explained by a lengthy transition period. Describing patterns of mental health services use may identify individuals who experience service needs more proximal or distal to the release date.

Younger veterans, compared to older veterans, accessed acute and specialised mental health services at higher rates in the public sector following release, and their intensity of use was almost 2-fold higher. This is consistent with contemporary studies identifying higher rates of mental disorders in younger veterans.18 This could mean that younger veterans may be more likely to medically release as the result of an incident mental illness unrelated to service19 or more likely to serve for a shorter period of time that includes a deployment to an active conflict for a tour of duty, resulting in a service-related mental illness.20 Overall, a better understanding of the unique mental health service needs of this young, veteran population is needed to ensure services are appropriate, accessible, and available.

Regardless of age, our data demonstrated that family physicians are a primary source of mental health care for veterans following release in Ontario. These data support previous reports from VAC that Canadian family physicians play a vital role in the health of the veteran population.21 Measures to ensure family physicians are prepared to support the mental health needs of CAF and RCMP veterans and deliver appropriate care are under way; for example, MDcme, a consortium of all Canadian medical schools, has created an online course to help primary care physicians recognise PTSD and learn about appropriate pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment strategies to manage PTSD.22

In our study, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse issues were the most commonly reported diagnoses occurring alongside ED visit data, and diagnosis codes associated with PTSD/acute stress reaction were more common with ED visits among younger than older veterans. Our findings support national and international data documenting high rates of common mental disorders and conditions, such as depression and anxiety, in the serving and ex-service populations.1,5,23 Rates of PTSD have been estimated between 4.7% (serving CAF members) and 8% (CAF veterans).1,5 Age has not been previously identified as a risk factor for PTSD in military and veteran cohorts.24 However, age may be representative of service-related exposures associated with higher rates of PTSD.24 While nationally representative surveys have been conducted to compare CAF personnel and civilian population mental health service utilisation,2 our national capacity to study these disorders among veterans has been limited. Currently, the administrative data diagnosis codes do not allow us to distinguish patients diagnosed with PTSD, making it difficult to identify veterans in need. Population-based, longitudinal surveillance of these disorders in the veteran population is needed nationally.

It is too early to tell how changes resulting from the CAF’s significant investment in workplace mental health1 might cascade forward into the veteran population over time. There is some evidence that these efforts have yielded improvements in CAF personnel both perceiving the need for mental health care, as well as getting those needs met.4 The baseline data reported in this study may allow policy makers to investigate increases or decreases in provincial veteran mental health services use as a measure of assessment. Further research investigating how patterns of utilisation change in future cohorts of Canadian veterans will be critical to understanding the long-term effects of these programmatic and cultural changes within the CAF.

Although this study is the first population-based description of mental health services use by veterans in the provincial health care system, it has a number of limitations. The data did not capture federally funded mental health services delivered in specialised inpatient facilities or OSI clinics by VAC or those provided through alternate insurance or out of pocket. Therefore, differences in service use by age at release may be related to differences in access to specialised mental health services, rather than true differences in need. Heavy users of VAC services may be underrepresented in our data, if they do not also receive assistance in the public health care system. In addition, we may have underestimated the true proportion of CAF and RCMP veterans using mental health services following release or requiring them. Our comparisons may be limited by our inability to capture a true denominator of healthy, younger, male veterans, who may be less likely to register for a provincial health card following their military career, as well as our inability to identify veterans who needed mental health care but did not access or receive services. This could affect the applications of our findings to health policy and programming. Further characterisation of mental health services use by sex, length of service, era of service, and physical health comorbidities is necessary to identify risk profiles of veterans who may require more acute or long-term mental health services following transition. In addition, although RCMP and CAF veterans are both eligible for benefits and services covered by VAC, their mental health needs may be different.

We were also unable to capture important details about service history, such as occupation, rank, or deployment history, and our data did not include information on Reserve Forces members who are an integral component of the CAF. Recent evidence suggests that specific occupations, deployments, and combat engagement may be connected to higher rates of mental disorders.25–28 This information would be important to understanding cohorts of veterans who may require mental health services following transition. However, we are able to study veterans who served during particular time periods, who may have been more likely to have experienced particular conflicts or peacekeeping missions.

Finally, we have not yet compared our mental health services rate directly with the general population. Selecting the appropriate comparator cohort from the Ontario general population is difficult, considering both the healthy worker and the healthy warrior effects.17 Individuals who serve in the military, especially those who serve longest, are by definition healthier than the general population, because they are healthy enough to maintain employment, and they are also healthier than military service members who retire early due to medical reasons. We are moving forward to identify a number of possible comparator options, based on recent work performed by Rusu et al.29 Rusu et al.29 compared CAF service personnel to an age- and sex-matched general population group, selecting from noninstitutionalised, employed, long-term Canadian residents who did not report a number of health problems that would make them medically unfit for CAF service. A careful selection of a general population comparator for CAF veterans will need to consider medical exclusions at the time of starting a military career, as well as medical exclusions and employment status throughout the period of service rather than at the end of service or for a particular index date.

Understanding how veterans use the mental health system is an important step to ensuring needs are met following the transition to civilian life. CAF and RCMP veterans are persistent users of mental health services from their time of release from service. Younger veterans are considerably more likely to access mental health services and have almost a 2-fold intensity of use compared to older veterans. A significant percentage of services is provided by family physicians in primary care; however, it is unclear if the civilian health care system’s current capacity and existing means of professional development are prepared to meet this challenge. Further research is needed to understand the extent to which veterans use both federally and provincially funded mental health services to better integrate these systems of care to support veterans and their families.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Mahar_Supplementary_File_CJP for Mental Health Services Use Trends in Canadian Veterans: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Ontario by Alyson L. Mahar, Alice B. Aiken, Heidi Cramm, Marlo Whitehead, Patti Groome, and Paul Kurdyak in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by a donation from the True Patriot Love Foundation via the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research (CIMVHR) and by financial support from the Kingston Brewing Company CIMVHR T-Shirt Campaign. In addition, this study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Zamorski MA, Bennett RE, Rusu C, et al. Prevalence of past-year mental disorders in the canadian armed forces, 2002-2013. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(suppl 1):26s–35s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sareen J, Afifi TO, Taillieu T, et al. Trends in suicidal behaviour and use of mental health services in canadian military and civilian populations. CMAJ. 2016;188(11):E261–E267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Delay to mental healthcare in a cohort of Canadian Armed Forces personnel with deployment-related mental disorders, 2002-2011: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Zamorski MA, et al. Perceived need for and perceived sufficiency of mental health care in the Canadian Armed Forces: changes in the past decade and comparisons to the general population. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(suppl 1):36s–45s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson JM, Van Til L, Poirier A, et al. Health and well-being of Canadian Armed Forces veterans: findings from the 2013 life after service survey In: Canada RDVA, editor. Charlottetown. Prince Edward Island: Veterans Affairs Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thompson JM, Zamorski MA, Sweet J, et al. Roles of physical and mental health in suicidal ideation in Canadian Armed Forces regular force veterans. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(2):e109–e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Richardson JD, St Cyr KC, McIntyre-Smith AM, et al. Examining the association between psychiatric illness and suicidal ideation in a sample of treatment-seeking Canadian peacekeeping and combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(8):496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Armour C, Contractor A, Elhai JD, et al. Identifying latent profiles of posttraumatic stress and major depression symptoms in Canadian veterans: exploring differences across profiles in health related functioning. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richardson JD, Contractor AA, Armour C, et al. Predictors of long-term treatment outcome in combat and peacekeeping veterans with military-related PTSD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(11):e1299–e1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richardson JD, Elhai JD, Pedlar DJ. Association of PTSD and depression with medical and specialist care utilization in modern peacekeeping veterans in Canada with health-related disabilities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(8):1240–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Veterans Affairs Canada. Mental health 2017. [accessed July 25, 2017]. Available from: http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/health/mental-health.

- 12. Rhodes AE, Fung K. Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: care to recall? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(3):165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacLean MB, Poirier A, O’Connor T. Province of residence at release and post-release—data from the income study In: Canada VA, editor. Charlottetown. Prince Edward Island: Veterans Affairs Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahar AL, Aiken AB, Kurdyak P, et al. Description of a longitudinal cohort to study the health of Canadian veterans living in Ontario. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2016;2(1):33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aiken AB, Mahar AL, Kurdyak P, et al. A descriptive analysis of medical health services utilization of veterans living in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study using administrative healthcare data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(a):351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahar AL, Aiken A, Groome P, et al. A new resource to study the health of veterans in Ontario. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2015;1(1):3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tansey CM, Raina P, Wolfson C. Veterans’ physical health. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Miner CR, et al. Bringing the war back home: mental health disorders among 103,788 us veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at department of veterans affairs facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garvey Wilson AL, Messer SC, Hoge CW. U.S. military mental health care utilization and attrition prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(6):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buckman JE, Forbes HJ, Clayton T, et al. Early service leavers: a study of the factors associated with premature separation from the UK armed forces and the mental health of those that leave early. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(3):410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pranger T, Murphy K, Thompson JM. Shaken world: coping with transition to civilian life. Can Fam Phys Med Fam Can. 2009;55(2):159–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MDcme. posttraumatic stress disorder: a primer for primary care physicians. [accessed January 23, 2017]. Available from: https://www.mdcme.ca/course_info/ptsd.

- 23. Goodwin L, Wessely S, Hotopf M, et al. Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population? Psychol Med. 2015;45(9):1881–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xue C, Ge Y, Tang B, et al. A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zamorski MA, Rusu C, Garber BG. Prevalence and correlates of mental health problems in Canadian forces personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan: findings from postdeployment screenings, 2009-2012. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2014;59(6):319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sundin J, Herrell RK, Hoge CW, et al. Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osorio C, Jones N, Jones E, et al. Combat experiences and their relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder symptom clusters in UK military personnel deployed to Afghanistan [published online March 10, 2017]. Behav Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Contribution of the mission in Afghanistan to the burden of past-year mental disorders in Canadian armed forces personnel, 2013. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(suppl 1):64s–76s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rusu C, Zamorski MA, Boulos D, et al. Prevalence comparison of past-year mental disorders and suicidal behaviours in the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian general population. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(suppl 1):46s–55s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Mahar_Supplementary_File_CJP for Mental Health Services Use Trends in Canadian Veterans: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Ontario by Alyson L. Mahar, Alice B. Aiken, Heidi Cramm, Marlo Whitehead, Patti Groome, and Paul Kurdyak in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry