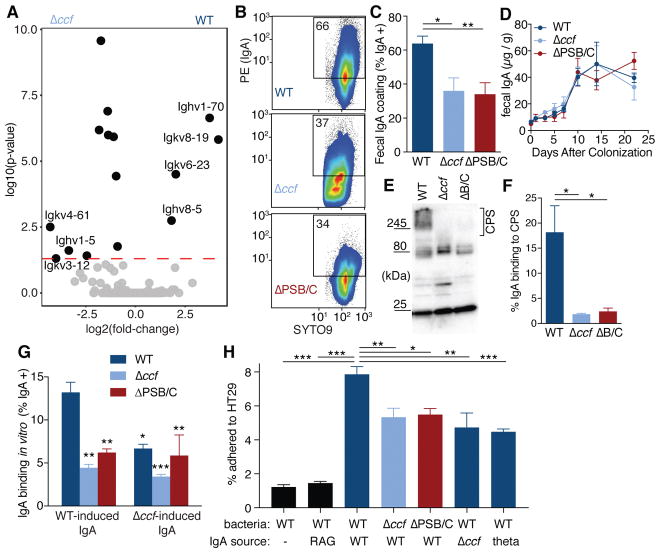

Fig. 3. B. fragilis induces a specific IgA response, dependent on ccf regulation of surface capsular polysaccharides, which enhances epithelial adherence.

(A) RNAseq gene expression analysis of RNA recovered from whole ascending colon tissue of mice mono-colonized with B. fragilis or B. fragilis Δccf (n = 3). (B) Flow cytometry plots and (C) quantification of IgA coating of B. fragilis from feces of mice mono-colonized with various strains (Tukey ANOVA, n = 11–12). (D) ELISA for total fecal IgA in mono-colonized mice (Sidak repeated measure 2-way ANOVA, not significant, n = 4). (E) Bacterial lysates from feces of mono-colonized Rag1−/− mice probed in Western blots with fecal IgA from B. fragilis mono-colonized mice and (F) quantification of the proportional signal from IgA binding to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) (over 245 kDa) (Tukey ANOVA, n = 3 mice). (G) Binding of fecal IgA extracted from mono-colonized mice to various strains of B. fragilis. Source of IgA is mice colonized with either WT B. fragilis or B. fragilis Δccf. Because ccf is expressed in vivo, IgA-free bacteria from feces of mono-colonized Rag1−/− mice were used as the target for IgA binding (Tukey 2-way ANOVA, *significantly different from WT bacteria with WT IgA, n = 3). (H) In vitro epithelial cell adherence assay using IgA extracted from Swiss Webster mice (or Rag1−/−, second column) mono-colonized with B. fragilis or B. thetaiotaomicron (theta; last column). IgA-free but in vivo-adapted bacteria were isolated from mono-colonized Rag1−/− mice (Tukey ANOVA, n = 4 mice as the source of bacteria) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).