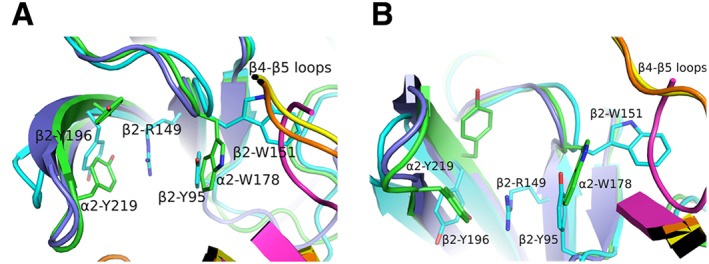

Figure 5.

Comparison of subunit interfaces. (A) Superposition of β2/α4 [in cyan or orange, respectively; PDB ID: 5KXI (Morales‐Perez et al., 2016)], α2/α2 [in green or yellow, respectively; PDB ID: 5FJV (Kouvatsos et al., 2016)] and nicotine‐bound AChBP [in purple or magenta, respectively; PDB ID: 1UW6 (Celie et al., 2004)]. The lack of one tyrosine in loop C of the β2 subunit allows the radical rotation of its Tyr196 to occupy space that in α subunits is occupied by the other tyrosine (e.g. α2‐Tyr219). β2‐Tyr196 along with the β2‐Tyr95 from loop A stabilize the β2‐Arg149 that rams the cavity. This is possible only after β2‐Tyr95 recedes towards the complementary subunit, occupying the space where in α subunits the loop‐B tryptophan (e.g. α2‐Trp178) is found. As a result, β2‐Trp151 presents an extreme rotational movement towards β4–β5 loop. Notably, the α2‐ECD pentameric structure shows that this rotamer of loop‐B tryptophan is also possible in α subunits, but not in AChBPs where this space is occupied by β4–β5 loop. (B) The same as (A) rotated by 90o. The coordinates of all the structures depicted were retrieved from Protein Data Bank (http://www.wwpdb.org), and PyMol (http://www.pymol.org) was used to generate the figures.