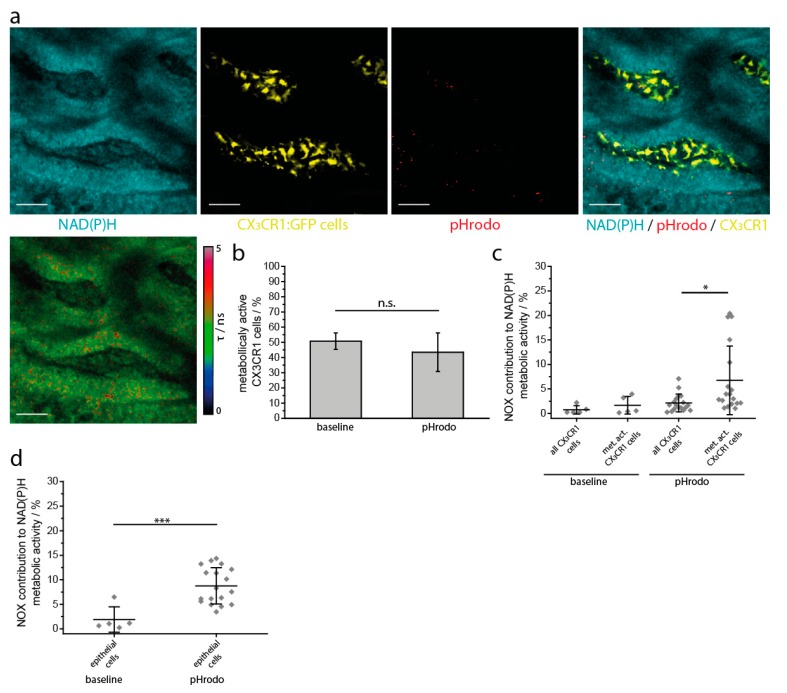

Figure 6.

Intravital marker-free FLIM reveals compartmentalization of NOX enzymatic activity in the small intestine upon inflammatory stimulation. (a) The upper row shows single and merged fluorescence images of intestinal villi in a CX3CR1-GFP mouse locally treated with S. aureus pHrodo beads: cyan represents NAD(P)H fluorescence, yellow represents GFP fluorescence, red represents phagocytosed pHrodo beads in a low pH environment. At physiologic pH the pHrodo beads are non-fluorescent. A volume of 100 µL with 10 [8] pHrodo beads was added directly to the exposed inner surface of the small intestine. The image in the bottom row represents the corresponding fluorescence lifetime image of enzyme-bound NAD(P)H of the entire tissue. Scale bar = 50 µm. (b) Overall NAD(P)H enzymatic activity in the myeloid compartment of the small intestine under steady-state conditions and upon S. aureus pHrodo stimulation, as measured by NAD(P)H FLIM. (c) NOX enzymes contribution to the overall NAD(P)H enzymatic activity in myeloid cells under steady-state conditions and upon S. aureus pHrodo treatment, as calculated from NAD(P)H FLIM measurements. (d) NOX enzymes contribution to the overall NAD(P)H enzymatic activity in the epithelial compartment under steady-state conditions and upon S. aureus pHrodo treatment. The graphs (b–d) display results acquired in n = 5 mice, 1 baseline area and 3–5 areas after treatment in each mouse. Analysis in (d) was performed using one-way ANOVA statistical tests (* p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001, n.s.: not significant).