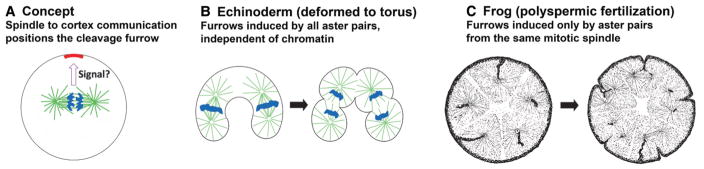

Figure 1.

Spindle-to-cortex communication in different systems. (A) In most animal cells the spindle sends a signal to localize the cleavage furrow, which then cuts through the cell in the plane defined by the earlier metaphase plate. (B) In mechanically deformed echinoderm eggs, aster pairs trigger furrows whether they grow from the same or different spindles. This shows that chromatin is not essential to general the furrow signal. (C) In polyspermic frog eggs, only aster pairs from the same spindle trigger furrows. These images are drawn from sections of fixed frog eggs after polyspermic fertilization. The left egg was fixed before first mitosis illustrating five sperm asters. Black trails mark the path of the sperm as it moves into the cytoplasm after entering the egg. The right egg was fixed during first cleavage. It illustrates cleavage with five spindles, where each furrow cuts through the sites previously occupied by a metaphase plate. Note the lack of furrows between spindles, unlike the Echinoderm system. (B, Redrawn from Rappaport and Conrad 1963, with estimated chromatin localization added in blue; C, modified from Brachet 1910.)